BAUHAUS 100: Eulogy for a Perversion

|Beatriz Colomina

The Bauhaus has died. It was in the middle of all the celebrations of its 100-year birthday that it succumbed, perhaps from the sheer number of events misinterpreting its history, thus manufacturing multiple legacies. It didn’t stand a chance. Too many expectations, too much pressure to keep offering a sense of “good design” in a world that has changed so radically. Paradoxically, the Bauhaus was so influential and affected so many different dimensions of the world that it was no longer able to offer us any advice. The planet itself has become a Bauhaus product, and it is dying. Good design is now deadly. The birthday party has become a wake.

Eulogies are usually about what never really was – about some idealized fantasy, a fiction, a projection. A shiny image is manufactured to cover up the complications and complexities, the strangeness, the eccentricities, the darkness, and the crimes – a reassuring or tranquilizing story that we can all buy into and share. But how did the Bauhaus become the blank slate onto which so many fantasies could be projected? Perhaps because the Bauhaus has long been a ghost fiction. The eulogizing started even before the school closed.

Despite its surface rhetoric of rationality, clarity, efficiency, smooth surfaces, etc., the Bauhaus was never straightforward. Bauhäusler (Bauhaus people) were engaged with everything that escapes rationality: sexuality, violence, esoteric philosophies, occultism, disease, the psyche, pharmacology, extraterrestrial life, artificial intelligence, chance, the primitive, the fetish, the animal, and plants. The Bauhaus was in fact a veritable cauldron of perversions.

Modern architecture is usually understood as having a normalizing function, establishing patterns that are stable, predictable, and to some extent standardized. The idea of architecture is intimately associated with the idea of the normal – perhaps it even sees itself as the caretaker of the normal. But the normal is not normal. It is a construction. Meanwhile, there is a hidden tradition in architecture of the transgressive, work that crosses the lines of the normal, complicating these lines, threatening the limit. Perversion comes from the Latin pervertere, “to turn away,” that is, turning away from normality. There is a relationship between the personal, often extreme pathologies of modern architecture and the call for a new normal.

If there is no such thing as modern architecture without transgression, what is remarkable about the Bauhaus, and perhaps the secret of its success, is the sheer density of transgressions of every kind. It was like a laboratory for inventing and intensifying perversions as a kind of pedagogical strategy. My eulogy is a celebration of the perversions of the Bauhaus, which have been repressed but were the source of its remarkable force.

PURGING

In his preparatory course at the Bauhaus, Johannes Itten introduced a regime of purging, following the principles of the neo-Zoroastrian Mazdaznan religion. The idea was to rid the body of “gross matter” through enemas, fasting for three weeks, eating a diet of garlic-based mush, and using machines for pricking the skin. As Paul Citroen, one of the students, put it:

“There was, among other things, a little needle machine with which we were to puncture our skins. Then the body would be rubbed with the same sharp oil which had served as a laxative. A few days later all the pinpoints would break out in scabs and pustules – the oil had drawn the wastes and impurities of the deeper skin layers to the surface. Now we were ready to be bandaged. But we must work hard, sweat, and then, with continued fasting, the ulcerations would dry out…. In actuality the puncturing didn’t go according to plan or desire, and for months afterward we would be tormented with itching.”

OCCULTISM

One of the intended effects of Itten’s regime was a trance-like delirium offering access to a spiritual domain – reinforced by deep breathing and concentration exercises run by Gertrud Grunow. Many of the masters, like Klee and Kandinsky, were into different forms of occultism and spirituality. Esoteric logic was not esoteric within the school. It was a kind of science. There was even a genre of spirit photography: Bauhaus objects were suspended in a cloud of ghosts.

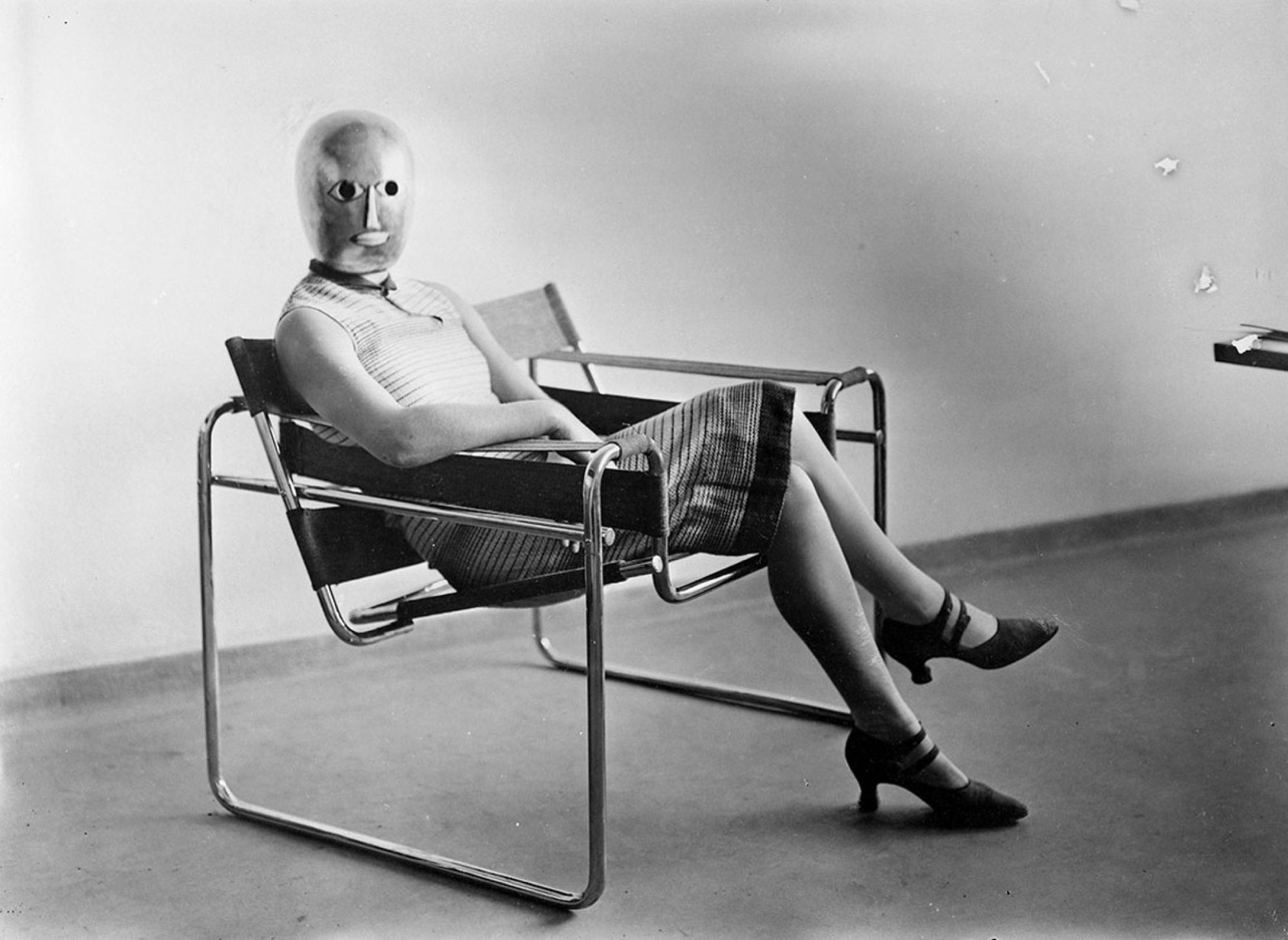

GENDER AMBIGUITY

There was continuous experimentation with the performance of gender at the Bauhaus. Gender inversion was the norm. Famously, women performed as men. Less famously, men cross-dressed, putting on lipstick and tights. Marcel Breuer sent a tantalizing card to Walter Gropius for his 41st birthday party, which included a double image of himself as a woman with the words:

“My dear Walter, keep our sweet secret. Eternally and truly yours.”

HAIR

The Bauhaus is unthinkable without the haircuts, which were used to embrace gender ambiguity, express modernity, and convey an otherworldliness. The Bauhaus student had to look like a Bauhaus student, and this meant visualizing transgression. One can do a catalogue of all the Bauhaus haircuts and their evolution, including completely shaving your head, as Itten urged his followers to do. As Lothar Schreyer remembered:

“When one day Itten declared that hair was a sign of sin, his most enthusiastic disciples shaved their heads completely. And thus, we went around Weimar.”

LEATHER

The leather of Luftwaffe jackets used by fighter pilots and in Berlin’s S&M and lesbian clubs made its way into the Bauhaus as a symbol of cultural rebellion and sensuality, in both men’s and women’s clothes. Chairs bound like corsets and leather straps lying around inexplicably in photographs suggest something illicit. The visual restraint of Bauhaus design was not a form of abstinence – it was actual restraint at, or over, the edge of pain.

EROTICISM

For all the official commitment to artistic experimentation on the way toward the Bauhaus’ sober industrial design, there was a continuous erotic charge to the school. The beach, for example, was never simply the beach. It was yet another space of transgression and intimacy between teachers, between teachers and students, and between and within genders. Naked bodies smoldering in the sun are tenderly photographed. Fourteen scantily clad men happily hold each other intimately while performing a kind of feminized cabaret, complete with delicately raised legs and a parasol.

THE AFFAIRS

Lotte Besse, later the chief architect in charge of the massive reconstruction of bombed-out Rotterdam after the war, was the first Bauhaus student allowed in the architecture workshop started by Hannes Meyer in 1927. Meyer had an affair with Besse while he was married with children. When he became director, Besse was asked to leave the Bauhaus because it wouldn’t look good. Walter Gropius had a sexual relationship with a student who was a war widow while still married to Alma Mahler, and while still with his mistress Lily Hildebrandt.

SWEATSHOP

After the preliminary course, all women were sent to the weaving workshop whether they liked it or not. As Gertrud Arndt put it:

“They all went to the weaving workshop, whether they wanted to or not…. I never wanted to weave. It was absolutely not my aim. No, not at all. All those threads, I didn’t want that. No, that was not my thing.”

Since weaving made the greatest profits for the Bauhaus, we could ask if weaving was a workshop or a sweatshop. Women sustained the Bauhaus but were diminished within it. It was a transgressive school in many ways, but not in gender politics. The weaving workshops became incubators of highly experimental work and theory almost as a form of resistance. But the level of exploitation and restraint cannot be overlooked.

WAR

Gropius even theorized his discrimination in his inaugural lecture. The artistic impulse was that of a man who experienced the horror of war rather than the “dearest ladies” who remained at home:

“The awakening of the whole man through trauma, lack, terror, hard life experiences, or love leads to authentic artistic expression. Dearest ladies, I do not underestimate the human achievement of those who remained at home during the war, but I believe that the lived experience of death to be all-powerful.”

Many students arrived at the Bauhaus directly from military service. Gropius himself was a “casualty of war.” He was injured and abandoned for several days in a bombed and ruined building. He later wrote, “First man must be constructed.” This is what the Bauhaus attempted to do: reconstruct the human.

The Bauhaus pedagogy and lifestyle took the human to the limit and beyond. Perversions were a doorway out of an immense trauma to an alternative version of the human. To celebrate the Bauhaus we have to celebrate all of its kinks and perversions, its all-too-human weirdness. Then we have to say goodbye.

Credits

- Text: Beatriz Colomina