What Is Black Style?

|MAX ROSSI

What’s the difference between appropriation and homage? Max Rossi spoke with Pratt Institute professor Adrienne Jones and Rachelle Etienne-Robinson—who recently curated the exhibition “Black Dress II: Homage” at the Pratt Institute—about the complexities of being labeled a “Black designer”—just before this year's Met Gala with the theme “Superfine: Tailoring Black Style.”

Designer Alessandro Michele created an uproar in 2017 when he unveiled Gucci’s “Cruise” collection amongst the frescoes of Florence’s Palazzo Pitti. But it wasn’t the Caravaggios or Botticellis that upset discerning members in attendance, it was a zip-fur jacket in Look 33. Critics quickly identified it as a blatant copy of Harlem designer Dapper Dan’s work from the 80s.

Caught in a chokehold, Michele called it a tribute to Dan, the go-to tailor for hip-hop stars, athletes, and socialites in the late 80s and early 90s. With his remixed luxury logos and motifs, Dapper Dan’s bootleg couture brought high fashion into conversation with streetwear decades before it became a mainstream trend, and the brush up with Gucci marked an unexpected rebirth for the Harlem native, as the luxury brand quickly scrambled to gather the funds to revive his defunct atelier. The incident also reignited conversations about the appropriation of Black culture and its white-washing in fashion.

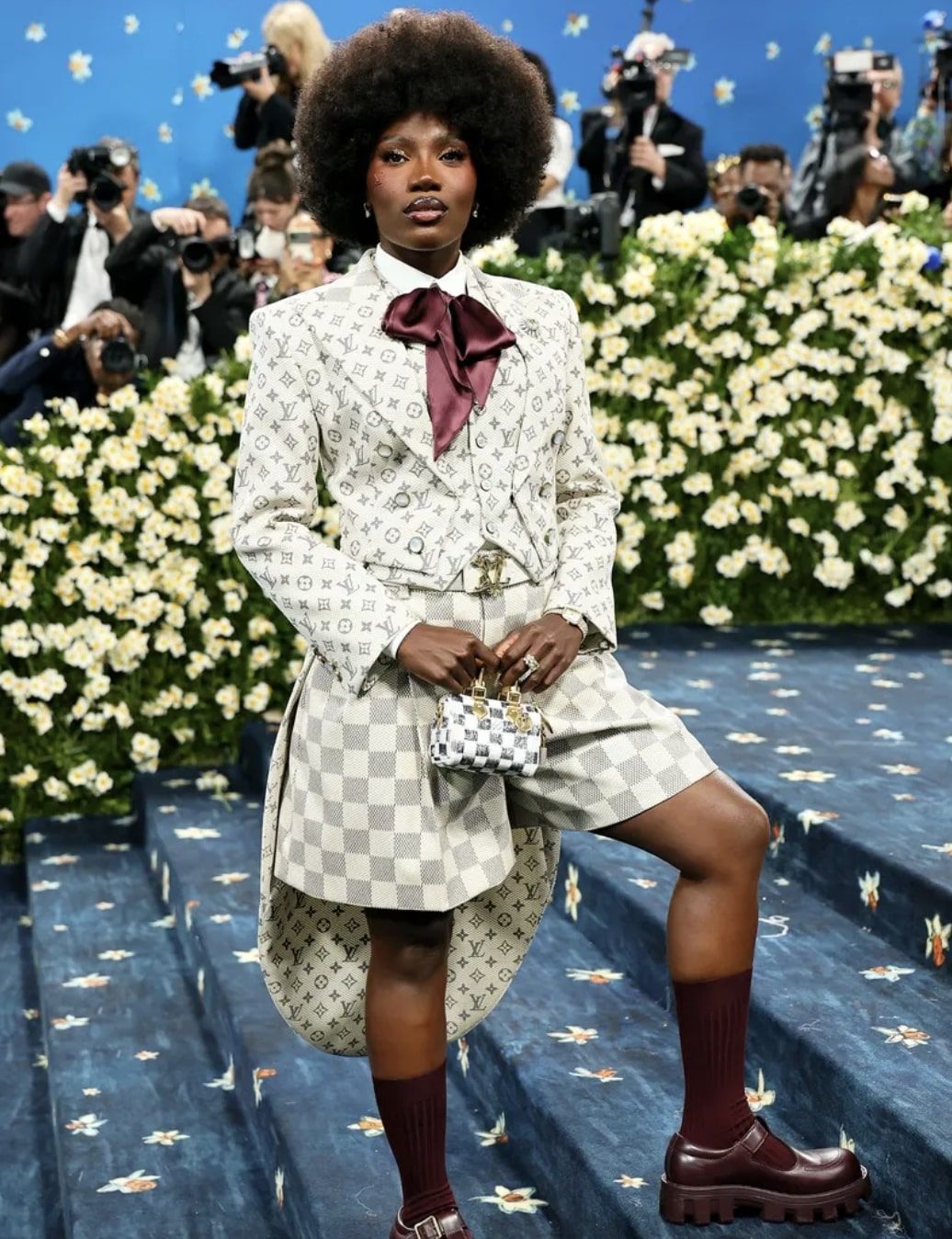

For Adrienne Jones, a professor at Pratt Institute NYC, the critical first step to rectifying this is visibility: “The need to be seen always comes first.” With this in mind, Jones has documented the often-overlooked history of Black fashion alongside Pratt alumna Rachelle Etienne-Robinson in the exhibition “Black Dress II: Homage.” Opening in February 2025, “Black Dress II: Homage” builds on the acclaimed 2014 exhibition “Black Dress: Ten Contemporary Fashion Designers” at Pratt Manhattan Gallery and expands beyond designers to spotlight a wider roster of Black creatives, who remain underrepresented in the industry but who were nevertheless honored in the theme of this year’s Met Gala, “Superfine: Tailoring Black Style.” Set across three rooms, the exhibition traces a history of overlooked triumphs and innovations that have shaped contemporary fashion. Following its February 2025 opening, Max Rossi spoke with Adrienne Jones and Rachelle Etienne-Robinson about the line between homage and appropriation and the complexities of being labeled a “Black designer.”

MAX ROSSI: “Black Dress II: Homage” picks up where the acclaimed 2014 exhibition left off. Is this a continuation or departure from the original?

ADRIENNE JONES: It’s a continuation, but it’s actually the exhibit I always wanted to do but couldn’t fully realize the first time due to limited budget and space. This time, my vision came to life, and I was able to expand on the original concept.

That’s what the story has always been about—there’s been a lack of diversity. Ten years later, we’ve been able to spotlight many people who have been working behind the scenes in fashion. You may have known their names but not necessarily been able to put a face to them. Even the first time around, I remember someone being surprised that designer Tracy Reese was Black. There’s such a lack of information about Black creatives.

MR: Over the past decade, the visibility of Black fashion creatives has increased, but do you think that power has actually shifted?

AJ : For me, during 2020—the year of George Floyd—I saw a window of opportunity for us to be seen. But I didn’t think it would last. And yet, it did. It became a trend. But with the current administration, it seems like that moment may have come and gone. For now…

MR: If we leave the U.S. aside for a moment, how do you think the situation has evolved across the Western world? I’m thinking about Europe—Paris, London, places that shape the fashion industry…

AJ: I think Europe has always been more open to people of color, valuing their skills and talents beyond just their skin.

RACHELLE ETIENNE-ROBINSON: I agree. We see it with figures such as Rihanna and other celebrities and how they’ve leveraged their influence and built partnerships with major European brands, expanding their reach beyond just the U.S. or the Caribbean. Even Pharrell [Williams]’s recent appointment at Louis Vuitton makes it clear that people on the other side of the pond are paying attention—and they have the resources to back these creatives.

MR: Yet, as a recent Vogue article points out, most of the creative directors appointed in 2025 are still white men, even despite diversity initiatives. What are your thoughts on that?

AJ: It’s not much different from 1973 and the Battle of Versailles [Fashion Show]. I feel like as long as there’s one person of color in the spotlight, the industry thinks it has done its job. But fashion has always been under white male influence—that’s nothing new. There’s still a lot of work to do.

RE-R: I’d add that one shift we’re seeing—especially at New York Fashion Week—is a growing number of creatives of color. There were a lot of Black designers presenting this season. And while there’s value in being backed by a major brand, autonomy over your own label is often worth more. With a big house, sentiment is fleeting—one moment you’re the industry’s darling, the next, you’re out. What would you rather have: five minutes of fame or control over your legacy? That’s the question designers have to answer for themselves.

MR: Black designers are often expected to represent a larger cultural movement. Can one simply create without the weight of being a cultural ambassador?

AJ: Personally, I don’t think that Black designers want to be known as “Black designers.” They just want to be recognized as designers, as creatives. Does that hurt or harm their brand? On the flip side, if we don’t talk about it and put it out there, how will anybody know?

RE-R: I agree with what Adrienne just said. Unfortunately, for people of color, if you are the only one in the room, you’re by default seen as the representative of your entire race. It also really depends on who your client is, right? And your intent... It depends on what both the designer and the brand are trying to represent. And as Adrienne said, often Black designers just want to be designers. But sometimes they need to also publicly support Black business, which can also hurt if they’re perceived as only servicing Black people. Those are the difficult circumstances that Black creatives have to navigate.

AJ: It’s a heavy burden to bear because you want to be known––at the end of the day, people just love beautiful clothes. One day, I went to a store and I mentioned that one of the biggest labels they were selling was a dear friend of mine––Byron Lars. They were ecstatic and told me they loved everything he does, yet had no clue who he was or what he looked like.

MR: What is the line between homage and cultural appropriation? Can white designers reference Black culture without exploitation or does the power imbalance makes it impossible?

AJ: If you look at history, Black style has always been something that somebody else shifts off of and then calls their creation. In the 70s and 80s, there were designers from Paris flying over here and hanging out in the clubs, looking at what the club kids were wearing. Then they went back and put that on the runway. I’m talking about big names here. This whole idea of appropriation is, for me, personal and a little painful because we’ve always been denied access and recognition, even though we were the ones who created and put that foot out first.

I saw it happening again and again, even with things as simple as wearing cornrows. When the model and actress Bo Derek started wearing cornrows, everybody went, “Wow, it’s this new thing, and we’ve never seen it before.” But that’s because you weren’t looking at us.

RE-R: I would like to add that I think the difference between “homage” and “appropriation” has to do with your intention. It also involves the creators you’re paying homage to. For this exhibition, we not only did lots of research but also directly contacted a large portion of the people we covered—it’s their exhibition. When people appropriate, they just want to use it for their own gain, whether that be commercial value, style, or influence. That’s the biggest difference.

MR: Are Black designers guilty of appropriation when pulling from cultures outside their own?

RE-R: Absolutely. But I think it depends. If you look at breakdancing, some of the performed moves are clearly influenced by Asian culture and martial arts. If you talk to the dancers, some but not all will tell you that they’d wake up on Saturday mornings and watch kung fu movies back in the day. Fascinated by the moves and positions they saw, they adapted them into hip-hop. The same scenario can be found in food, art, and even design. If somebody is using Kente cloth and then making it into a kimono silhouette, it’s a very fluid process, but it all goes back to your intention and whether you’re trying to claim something for yourself or openly admitting what you were inspired by.

MR: Black aesthetics have shaped everything from luxury styles to streetwear, yet streetwear remains the primary mode through which Black fashion is seen. How do we expand beyond that default?

RE-R: One of the great things about this exhibition is that we are highlighting the diversity and wide spectrum of the types of genres we present.

As far as why people tend to associate Black design with streetwear, I think that hip-hop had such an influence in the late 80s and 90s that even major brands like Ralph Lauren and Tommy Hilfiger were following suit and taking ideas from the likes of Karl Kani and April Walker. I think it has a lot to do with the commercialization of these major brands who suddenly flooded the industry and stores.

Another aspect is that that’s what people see––they see what young people are wearing and they automatically draw conclusions, regardless of the fact that we had Byron Lars and Fabrice [Simons], who were doing beautiful evening attire and beaded gowns at that time. But that wasn’t getting attention, everyone’s eyes were on these hip-hop artists and what streetwear folks were wearing.

MR: In conclusion, what do you think is most needed to support the next generation of Black creatives? Is it mentorship, funding, or reshaping the system altogether?

AJ: I would say D, all of the above. It’s going to take all of that for real change to happen, but capital comes first.

RE-R: Walking back into this gallery after a couple of weeks, I couldn’t help but think how impactful this would’ve been for me as a student. You might have heard of one or two designers, but when you see the list of all the names we’ve showcased, you wonder, “How did I not know about this?” Seeing the garments—even things like archival beauty products from people like Josephine Baker—is mind-blowing. It really makes you realize how deep our history goes.

Having something like this as a permanent space is essential for current students because they need to see it and keep coming back. We’re always adding to it—it’s never stagnant. We discover new designers all the time and there are still so many more we don’t know about or haven’t yet highlighted. It’s important for the youth to see something like this so they can see themselves in it and think, “Wow, I can do this,” or at least have a point of reference.

AJ: And that’s something that we’ve said continuously throughout this interview––the need to be seen. The need to be seen comes first. That’s of the utmost importance.

Credits

- Text: MAX ROSSI

Related Content

DOECHII on Swamp Rap, Alter Egos and Narcissistic Exes

DALLAS: A Template For The Future City In 41 Points

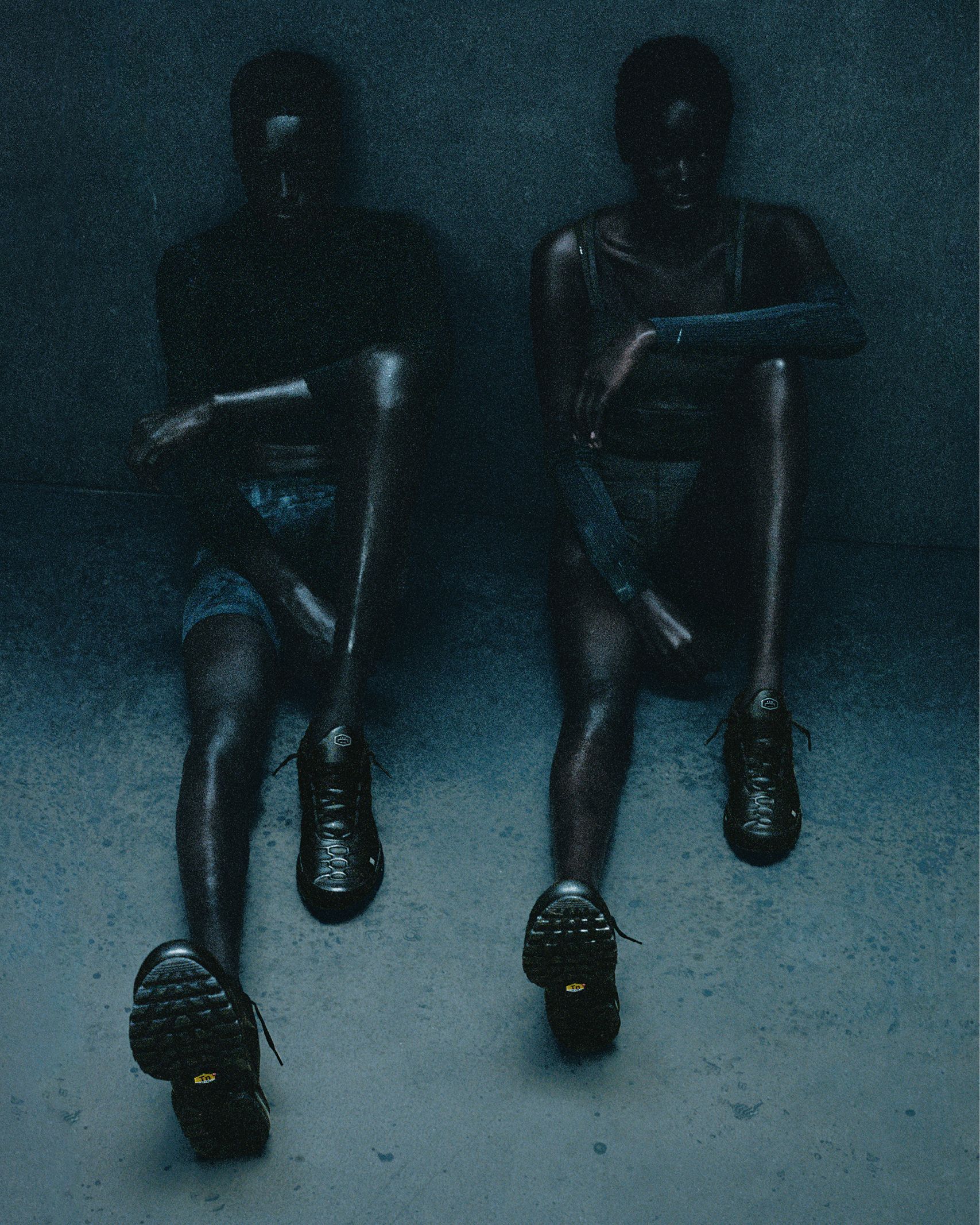

Never Growing Up: GABRIEL MOSES and SAMUEL ROSS’ ACW_NIKE TN98

The Last World: HANNAH BLACK Investigates Mommy Issues and Death

The Story Behind the Monstrous Rihanna Sculpture at this Year’s Berlin Biennale

The Politics of Beauty: Tyler Mitchell

Dozie Kanu: EVIL