The Story Behind the Monstrous Rihanna Sculpture at this Year’s Berlin Biennale

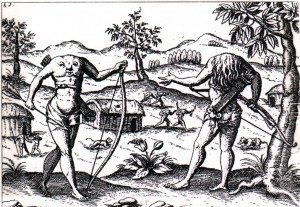

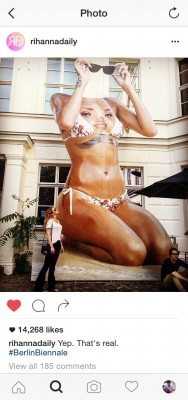

The work of the Colombian artist Juan Sebastián Peláez has a circuitous relationship to power. After he bought billboards in Bogota and pasted them with pictures of the sky (as a way of deleting ad space), the billboard agency liked how they looked and began using the tactic to sell empty billboards. His giant sculpture that opened this week at the Berlin Biennale operates in a similar fashion, subverting propaganda by inflating it to new proportions. The sculpture features Rihanna photoshopped as an Acéfalo, a headless monster with a face in its chest that was used by early European explorers to depict the natives of the Caribbean. This racist misappropriation has been remixed by Peláez with the most iconic Caribbean celebrity of today, morphing into the most Instagram-able artwork in a biennial governed by the inventors of the #artselfie. This mass re-circulation reaffirms the celebrity appeal of monsters, or perhaps the monstrous nature of celebrity.

032c’s Thom Bettridge spoke with Peláez, who shared his archive of present-day Acéfalos.

Tell me about how you became interested in the Acéfalo.

I guess I have to mention that I was born in Colombia, but my family left to live in Miami when I was like two years old, like a lot of Latinos in the 1980s and 90s. So I was like a gringuito, I hardly spoke Spanish but my name was Juan — just like MANY Latinos in Miami. And my only relationship with Colombia was through movies and cartoons. I remember watching Captain America, and the character Mati was huge for me because he formed an image of what it was like to be South American. He was from “The Amazon” and that meant that he was like my cousin. And it was weird because he had the WORST powers. He never killed anybody. He was just like the chauffeur for the other cool fighters. And he had a monkey on his shoulder. And that was cool. I kinda got the idea that Latin America was where chauffeurs came from and that we could talk to animals. But we sucked at fighting. Then, when I was 12, my family went back to Colombia and I was really surprised that there were cars and buildings. And I was surprised that people couldn’t talk to animals. So that’s when this whole idea started. I finished school there and started my arts degree, and it was always a thing that I came back to. The image of headless people comes from WAY back. It started in white western cultures and it was a way to describe the image of “the other,” the savage.

Who originally made these images?

When a certain empire would go out and explore other areas, they would find a bunch of weird gangs of naked “barking” people, and one of the ways of representing them was by beheading them. Usually we assume that our logic — our reason — is in our heads. So by putting a face in someone’s chest, you are saying that he has no rationality, that he is a beast. They are not like “us,” so we can do whatever we want with them. So Columbus travelled to America and discovered a bunch of chauffeurs. It’s like animals. Animals have no “neck” that clearly separates their logic from their body. This is an image and an idea that’s been used for HUNDREDS of years. But the last time it appeared was in Latin America. There was this one famous image by Sir Walter Raleigh. He was an English explorer and he made a drawing of an Acéfalo. He said they lived in South America and they were called Ewaipanomas. And when he got back to Europe that image was printed and everybody got the idea of what the people from the New World were like. So what I did, was look for people that were born in the same region — the Caribbean, the North Coast of South America, et cetera — and do the same process. To make them look like they were supposed to look 500 years ago. I started off with Ricky Martin and J-Lo, and then years later I did Rihanna, Falcao, Sofía Vergara, et cetera.

I mean, this all makes sense, because in a way celebrities are still represented in this way. Pure body. No Mind. Total otherness.

It’s all the same today as it was 500 years ago — propaganda, advertisement, the creation of an image to reinforce power. Today we just have glossier paper.

The sculpture has become one of the most shared artworks from the Berlin Biennial on social media. Do you mind that people who see it are unaware of the backstory?

No. I mean, this is just another monstrous sub-product. Just like everything else. But now that it’s at a museum, people believe that they have to think about it. And make up stories. But people don’t make up stories about why Mati is a chauffeur for a bunch of First World hipsters. People told me that they thought the piece was misogynistic. Obviously, it is. I was copy-pasting something misogynistic.

Interview: Thom Bettridge, images: Juan Sebastián Peláez