DALLAS: A Template For The Future City In 41 Points

|ZAC CRAIN

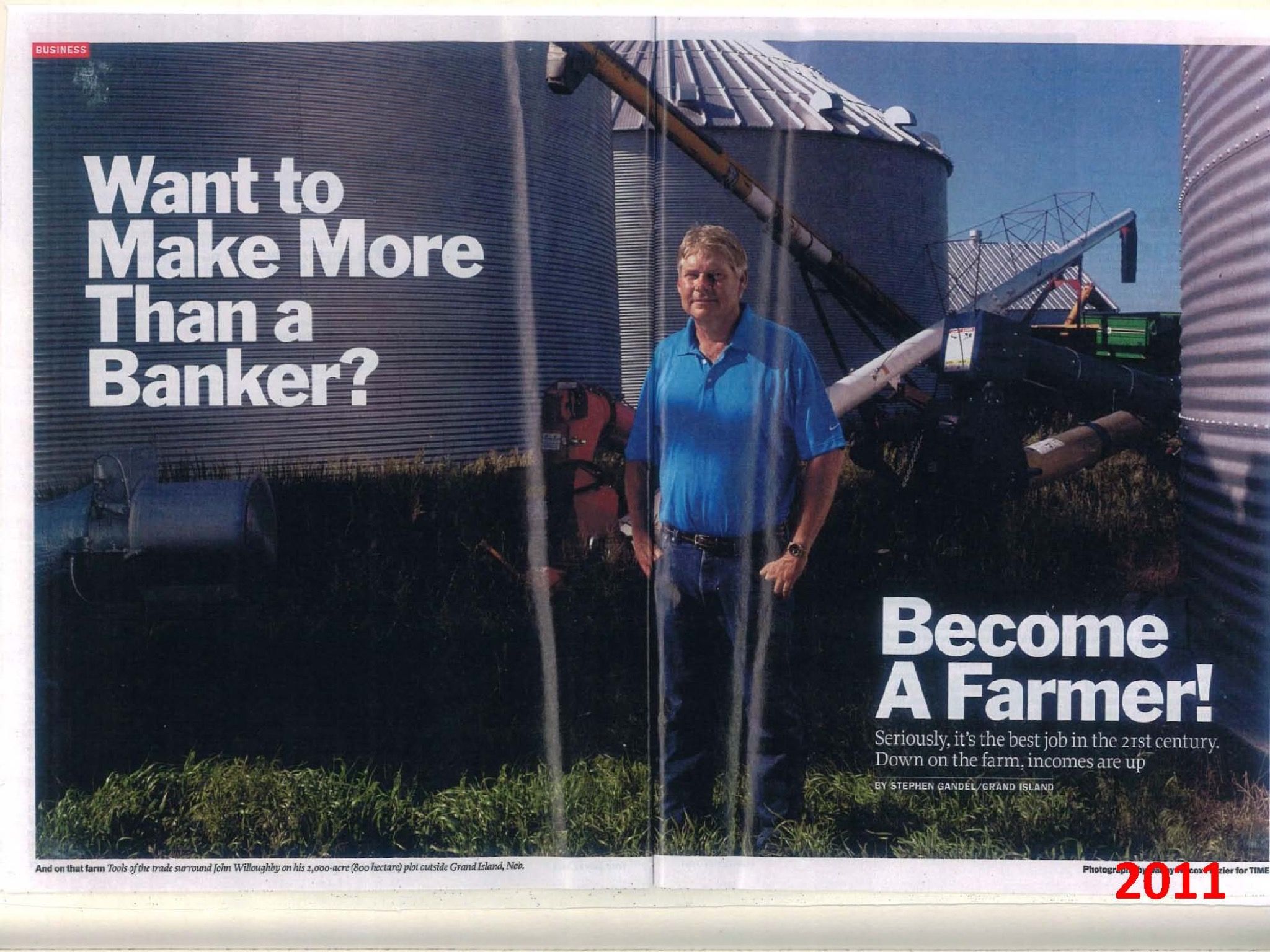

Dallas was a farming town at first.

At the beginning of the 20th century, it was the largest inland cotton market in the world. Then, in 1930, just east of the city, they found oil. Dallas was suddenly at the center of the American petroleum industry. When the US entered WWII in 1941, Texas pumped even more to meet military needs, and the government invested in the construction of pipelines – setting Texas oil up for its post-war glory years. Today, there are pipelines owned by Dallas-based petroleum transport company Energy Transfer in 41 states.

1. If you come to Dallas looking for the city from the television series, you’ll never find it. That Dallas does not exist. It never existed. David Jacobs, the show’s creator, had never been to the city before writing the first episodes. He later realized that what he had been writing was Houston. The result, which aired from 1978 to 1991, was a caricature based upon a stereotype of a different place altogether. The only cattle anywhere inside the city limits is the herd of 40 longhorn sculptures near the Kay Bailey Hutchison Convention Center. You won’t find any businessmen wearing cowboy hats. You probably won’t see anyone in a Stetson, apart from a fashion photographer between shoots at a downtown hotel coffee shop, sipping an espresso made with single-origin beans from a local roasting studio.

2. There is an idea, though, implied in the show and more explicit now, that connects fiction to real life: the Dallas–Fort Worth metropolitan area as the de facto capital of America’s heartland. It is almost as if the series’ fictional alternate reality made it true. The city used to be the place where rich Texas ranchers’ wives would come to get their ready-to-wear dresses and fur coats from Neiman Marcus. Now it is spiritually that for a much wider swath of the country.

3. Today, Dallas looks more like the version you see in RoboCop than it does the city from the TV show. Yet the version from Paul Verhoeven’s 1987 futuristic social satire never existed, either: that film was set in a dystopian Detroit. But it was shot in Dallas, and it is unmistakably Dallas onscreen, its neon and glass slicing through the glitter and grit of a place always looking ahead, and whether it is running from the past or toward the future or both remains unclear.

4. The future isn’t New York or Los Angeles. It isn’t the coasts; they’ll be underwater. The future is Dallas, a city that has already figured out how to make life work in a hostile environment, in terms of climate and in terms of politics, located in a part of the state where both the summers and the debates are fiery and dumb. (Books are being banned again, for starters, and the practice accurately reflects the state government’s views regarding abortion and trans rights.) The city and its surrounding suburbs annually rank among the country’s fastest-growing areas, a migration pattern that has been accelerated by the pandemic. According to the US Census Bureau, New York lost 328,000 residents from 2020 to 2021. Los Angeles lost 176,000. San Francisco: 116,000. “The de facto capital of America’s heartland” gained more than 97,000 new residents during that same time. These new residents decided that Dallas is the future, too. The sentiment is notable, but not new.

5. In 1855, a group of French, Belgian, and Swiss immigrants settled on the banks of the Trinity River, just south of what is now downtown Dallas. They were led by Victor Considerant, a disciple of the French philosopher Charles Fourier, and their aim was to build a socialist utopian commune that would put into practice some of Fourier’s teachings. (Many of Fourier’s other ideas are best left ignored. Among his lesser-known writings are predictions that six moons would eventually orbit the planet, that humans would evolve to all be at least seven feet tall, and that oceans would one day taste like lemonade.) “I did not say to you: let us enrich ourselves and live happily and freely in Texas,” Considerant wrote in 1854, in a book titled Au Texas!, outlining his plans to build a settlement there after his first trip to the state a year earlier. “I said: Let us create in Texas a haven for progressive thought which repels the Old World; let us there open a land of studies, of expansiveness, and of free experience for all ideas in the search for the divine Law of humanity.”

6. The commune they called La Réunion failed after only 18 months, thanks to – depending upon which account you believe – poor leadership, internecine conflict, the harsh terrain and forbidding climate, and/or the unwelcoming nature of their fellow Texans. As he wrote in Au Texas!, Considerant had been excited about the possibilities of the community he intended to build, but less so about the exact location where it ended up. It did not match the Texas he remembered from his previous visit, the land that captured his imagination and compelled him to move ahead.

7. La Réunion exists now mostly in name alone, via La Reunion Publishing, an imprint of Deep Vellum, both founded by Dallas transplant Will Evans. Last year, La Reunion re-issued the long out-of-print The Accommodation: The Politics of Race in an American City, by Jim Schutze. First published in 1986, the book became something of a secret instruction manual to the city – a shadow history, with photocopies and PDFs traded like samizdat before its recent return to shelves.

8. Dallas (the TV show) is one fiction about the city, but for many years, Dallas believed in another made-up story about itself: that there was no good reason for it to survive, let alone thrive, and that its success was borne of the will of its people, specifically its business community. In The Accommodation, Schutze describes a flyer for a civic bond issue in the 1980s that spells out precisely this conviction: “There is no real reason for a place called DALLAS. No harbor drew people here, no oceans, no mountains, no great natural beauty. Yet, on a vast expanse of prairie, people made out of Dallas what it is today: the shining city of the Sunbelt, a city of opportunity, a great place in which to live and work.”

9. The most important part of The Accommodation is its history of the Dallas Citizens Council. As Schutze writes, Dallas’ oligarchs consolidated their power early in the 20th century, when a group of 50 or so businessmen came together informally to bring the Texas Centennial Exposition to the city’s Fair Park in 1936. After that success, the once ad hoc concern was codified into the Citizens Council and became the ruling class. For decades, that elite group made all the decisions for the city, including choosing the officials who would rubber stamp them. (That would not change until 1991, when the city adopted a new form of government that called for 14 single-member council districts, with only the mayor elected at large.) The council’s decisions, its members said, were based on “what was good for Dallas as a whole” – and “Dallas as a whole” always meant “white people.” The Citizens Council now has a Black CEO, Kelvin Walker, but its role in civic affairs is not as prominent as it was in the turbulent postwar years. And the damage the group did during those decades in power is far from being repaired.

10. The biggest scars from that time are the highways and other urban “improvement” projects that plowed through some Black neighborhoods and completely erased others, displacing thousands of people and brutally dividing those who were left, slicing up formerly tight-knit communities with tons of concrete. By weaponizing eminent domain statutes, the city cost at least 1,000 Black families their homes between 1947 and the late 1960s.

Today, Dallas is home to some of the world’s biggest energy, technology, and telecommunications companies – and there are 41 colleges and universities in the area to recruit from.

11. This disparity brought the Reverend Peter Johnson to Dallas. Johnson was just 24 years old when he was sent to the city by the Southern Christian Leadership Conference in fall 1969. He was using Dallas as a base for a couple of months as he traveled to theaters around the Southwest, promoting a documentary about the late Martin Luther King Jr. to raise money for King’s widow, Coretta. Dallas was the only one of 800 cities around the world to refuse to screen it. That made him mad enough to stay. By New Year’s Eve, 1969, Johnson had organized a protest march that would have shut down the nationally televised Cotton Bowl Parade, forcing Mayor Erik Jonsson to negotiate with Black homeowners who were losing their homes in the Fair Park area.

12. Now in his 70s, Reverend Johnson is still involved in community activism, lending his voice and presence to rallies and marches. He is working with rapper The D.O.C. on an anti-gun project aimed at teenagers, using rap to deglamorize something he feels rap helped glamorize in the first place. The D.O.C. is someone whose words you have likely heard before, but from a different voice: he wrote lyrics for N.W.A. and went on to work with Dr. Dre and Snoop Dogg on The Chronic and Doggystyle.

13. When The D.O.C. came back to Dallas 20 years ago, he rekindled a brief romance with Erykah Badu. They had both come up through Dallas’ nascent rap scene in the late 80s, back when he was Dr. Tray, and she was Apples. The relationship didn’t last, but it did produce a daughter, Puma.

14. Badu has been in and out of the spotlight outside her hometown, but in Dallas it has always been aimed at her. Her annual birthday concert, at the end of February – a tradition restarted in real life this year, after a two-year pandemic pause that she spent streaming like a gamer – is the stuff of legend, attracting everyone from Dave Chappelle to Willow Smith. You can usually see André 3000, the father of Badu’s son Seven, lurking in a corner.

15. Badu exports Dallas to the world while bringing the world to Dallas. So did Stanley Marcus. Until his death in 2002, the longtime owner of Neiman Marcus was the city’s unofficial ambassador, who traveled far and wide but always came back home.

16. The late “Mr. Stanley” made sense as an avatar for Dallas, because Dallas is a shopping town – and it has always known what to buy. His former palace, Neiman’s nine-story downtown flagship, has retained its allure even as it has been joined in the neighborhood by scrappier, but no less high-end upstarts such as Traffic and Forty Five Ten.

Dallas’ major league sports teams include the Dallas Cowboys (NFL), the Texas Rangers (MLB), and the Mavericks, who Nowitzki led to victory in the National Basketball Association Championships in 2011. Number 41 was named the NBA’s most valuable player that year.

Dallas is where it is, but it could have been anywhere. And it could be reproduced, popping up as a seastead, a Martian colony. It’s the model terraform, a pioneer’s fantasy.

17. But shopping in Dallas is bigger than clothes: it’s anything and everything, especially art and architecture, which are treated here as the ultimate luxury goods. This attitude makes Dallas more honest than most places. And because there is no pretense of a division between art and commerce, you are always surrounded by both. The city buys 3,000-pound Harry Bertoia sculptures for the downtown branch of the public library and contemporary art by the warehouse-full. Literally: Cindy and Howard Rachofsky have amassed such an extensive collection, numbering almost 1,000 pieces, they couldn’t fit it all in the gleaming box of their Richard Meier– designed home. The art is now housed in North Dallas, in what they simply call The Warehouse, open to the public for free two days a week – all funded by the Rachofsky oil and gas fortune.

18. The city buys so many buildings by Pritzker Prize–winning architects that you might think they had gotten a bulk rate. I’m not being hyperbolic: if you stand in the middle of the downtown Arts District, you will see a Rem Koolhaas in one direction (the Dee and Charles Wyly Theatre), a Norman Foster in another (the Margot and Bill Winspear Opera House), and I. M. Pei’s Morton H. Meyerson Symphony Center in another. If you squint, you may catch a glimpse of Renzo Piano’s Nasher Sculpture Center; scooch up a lamp post and you might spy Thom Mayne’s Perot Museum of Nature and Science. Look toward the skyline and there is that RoboCop vista with buildings by Pei and Philip Johnson. Almost all of these buildings are named after someone. Almost every public space is, too. All the conspicuous consumption is the endpoint of a show-your-wealth arms race that has progressed from fashion and cars to art to homes to buildings.

19. Dallas’ knowing what to buy applies to drugs, too. On the edge of downtown, the Starck Club – namesake of Philippe Starck, who designed his first significant US project here – was the place that popularized a drug called Adam, which you most likely know better as ecstasy, MDMA, molly. When the discotheque opened in May 1984 with a performance by Grace Jones, the drug was still legal, and bartenders and cigarette girls sold it openly. Very openly: so much ecstasy moved across the club’s black terrazzo floors that it was made illegal in 1985. The Starck lasted until July 1989, by which time it had played host to Stevie Nicks, Princess Stephanie of Monaco, and a young George W. Bush, to name a few. The Starck Club is one reason I think of Dallas as a sort of glamorous small town. Here, everyone knows everyone, and everyone is someone.

20. If this small town was ever a glamor capital, Marcus was its glamor mayor. In his 1974 autobiography, Minding the Store, he recalled Coco Chanel’s 1957 visit to Dallas to receive the Neiman Marcus Award for Distinguished Service in the Field of Fashion: “[The president of her American perfume company] told me privately that Mademoiselle Chanel was eager to visit a ranch, so we gave a Western party at my brother Eddie’s Blackmark Farm, with a ranch-style dinner and roping and bronco riding exhibitions. It turned out that she didn’t like the taste of barbecued meat and the highly seasoned beans, so she dumped her plate surreptitiously under the table. Unfortunately, the contents hit the satin slippers of [cosmetics magnate] Elizabeth Arden, who was seated next to her. We topped the party off by putting on a bovine fashion show, with the show cows all adorned with headdresses in the latest fashion colors. She loved the spoof.”

21. Neiman Marcus didn’t just carry Balenciaga – the owners also knew Cristóbal. In Minding the Store, Marcus recounts calling on the couturier in Paris during one of his first post-WWII visits, an attempt to secure the exclusive rights to sell Balenciaga perfumes in the United States. He also brought Christian Dior and Dior’s protégé Yves Saint Laurent (among others) to Dallas for various celebrations, while importing the fashions of Carolina Herrera and Emilio Pucci – to name just a few designers who found a powerful advocate in Marcus. He gave Pucci the idea to turn his scarves – “unusual in design, brilliant in coloration” – into blouses and dresses, which jump-started the Italian designer’s international career. At the same time, Marcus was exporting the idea of what a department store – and what Dallas – could aspire to be to the rest of the state, the country, and the world.

22. When Coco Chanel came to Dallas, Marcus staged a rodeo for her. But when Karl Lagerfeld brought the annual Chanel Métiers d’Art fashion show to Dallas and Fair Park in December 2013, he staged his own rodeo. Along with it came Kristen Stewart, Vogue’s Anna Wintour and André Leon Talley, and 900 or so models, actors, jet-setters, and hometown socialites. An elaborate rodeo barn and roadhouse were constructed for the occasion. The show itself got mixed reviews from the locals – “It’s as if Karl and Ralph Lauren were dating,” someone said – but everyone enjoyed the unofficial after party at the Round-Up Saloon, a gay country- and-western bar and dance hall.

23. Other than its clientele, the Round-Up is no different than any dance hall you might find in Texas: a sweeping plain of a dance floor populated by boot-scooting line dancers, the whole scene glowing in the indirect light of beer signs. (I have been forcibly removed from that dance floor by the DJ himself. If memory serves, he did so for good reason: my moves that evening were closer to moshing than line dancing.)

24. Speaking of dance halls, marvel at this infamous Longhorn Ballroom marquee from 1978:

TONITE

SEX PISTOLS

JAN 9 MERLE HAGGARD

25. The juxtaposition reminds me of a ’fit pic I recently saw on a friend’s Instagram feed, captioned: “Wrangler with Isabel Marant just feels like Dallas to me.”

26. Dallas feels like something between those two Chanel junkets, residing somewhere between the names on that marquee, somewhere under the Wrangler and Isabel Marant. Dallas is an idea and a place, and its essence gets lost in any attempt to locate it within a binary: it’s not Wrangler or Marant, despite new arrivals’ attempts to choose between the two – or worse, ironically hybridize them. Both Dallas the place and Dallas the idea are moving targets, two forms repelling each other, never to touch.

27. Dallas has always wanted to be an international city. Even La Réunion aspired to that. And it is an international city, just not in the way it wants to be – not in reputation or stature, no matter how many times it trumpets whatever new toy it is shaking in its jaws as being “world-class.” But in 2016, more refugees (from 28 countries) resettled in Dallas than in any other metropolitan area in the country, according to the US State Department. Some transplants are escaping from somewhere, but many are running toward Dallas specifically, entwining the city with the future.

28. The most famous of Dallas transplants is Dirk Nowitzki, who had his No. 41 retired by the Dallas Mavericks in January 2022. After arriving from Würzburg, Germany, in 1998, he played in Dallas for 21 seasons and brought the team its first (and, so far, only) championship in 2011. After more than two decades as the talisman of our professional basketball team, Nowitzki is as much a Dallasite as anyone else is. Maybe more than anyone else, because not only is Nowitzki proof that the city can “win,” he chose Dallas. He stayed. And because he stayed, he and his wife, Jessica, are rewarded with the kind of loyalty found only rarely outside of cults.

29. Dallas defers to those who could have left and chose not to – Erykah Badu among them. Part of that regard is due to an abiding inferiority complex that has persisted since November 22, 1963, when President John F. Kennedy was assassinated in Dealey Plaza, inflaming a collective civic lack of self-esteem. That sentiment coalesced after JFK, but it was already there as an undercurrent, because part of always selling yourself means that, on some level, you consider it necessary, that you feel unworthy to stand on your own attributes. The attitude goes back to that myth about the city having no reason to exist, even all the way back to La Réunion and the belief that a better world was possible, or necessary, and that Dallas hadn’t gotten there yet.

30. Dallas’ inferiority complex is not all bad. It creates a drive that inspires people to try things. The city moved an entire river once, relocating a 13-mile stretch away from downtown to flow between a set of levees – supposedly because the Trinity kept flooding, but also to free up valuable real estate, which bankrolled several fortunes. Dallas built Klyde Warren Park above a highway, seemingly out of thin air. (The park is named for the teenage son of Kelcy Warren, the billionaire CEO of Energy Transfer Partners, the primary company behind the Dakota Access Pipeline protested at Standing Rock. Warren’s natural gas fortune funded 10 million of the 90 million-dollar public-private project, thus earning him naming rights. Dallas may not be in the firm grip of the Citizens Council anymore, but the city’s powerful still like to flex.) South of downtown, the city is building a second park above a highway, testing the limits of engineering with five wooded acres and a restaurant–retail complex hidden under a sloping lawn.

31. “Trying” may be the most essential civic virtue here. There is no real Dallas style – of food, music, art, architecture, anything. But there is a Dallas style of trying. It is the pervasive feeling that nothing is out of reach, that everything can at least be attempted – like making lemonade of the ocean. What I mean is, people have been trying things here since La Réunion.

32. Maybe the constant striving to improve upon even the mundane is why Dallas’ best museum is arguably a shopping mall: NorthPark Center, where the walls and walkways are filled with art by Roy Lichtenstein, Frank Stella, Mark di Suvero, Jonathan Borofsky, Sterling Ruby, Tony Cragg, Jim Dine, Pamela Nelson and Robert A. Wilson, Joel Shapiro, Katharina Grosse, Siobhán Hapaska, Michael Dean, Leo Villareal, Tom Friedman, Mimmo Paladino, Iván Navarro, Sergio Storel, Liam Gillick, Costas Coulentianos, Leonardo Drew, Michael Craig-Martin, Barry Flanagan, Alain Kirili, Thomas Houseago, Anthony Caro, Antony Gormley, Huma Bhabha, and KAWS (whose prints recently replaced Andy Warhol’s Ads, 1985, a longtime fixture). Again: Dallas surrounds you with art and commerce, and at this temple of conspicuous consumption, window shopping means there is something to covet on both sides of the glass, masterpieces to admire as you stroll from Burberry to Balenciaga to Bottega Veneta.

The number 41 is not only written on Nowitzi's jersey. It represents the chemical element niobium, which is an essential part of the special steel used in rocket engines and gas pipelines. The number 41 fuels Dallas in a lot of ways, when you think about it.

The Mavericks retired the number 41 in 2019, when Luka Dončić was rookie of the year, making NBA history as the new European all-star. Next season, due to Covid-19, there were Dallas players missing from a total of 41 games. By then, Dončić had a new career high: in a single game in the 2020–21 season, he scored 41 points.

33. NorthPark’s developer, the late Raymond Nasher, turned the rest of his collection into an actual museum: the aforementioned Nasher Sculpture Center. But the city’s newest stand-out museum is AT&T Stadium, where the Dallas Cowboys play. There are more than two dozen mostly large-scale pieces inside and out, including works by Anish Kapoor, Doug Aitken, Olafur Eliasson, Lawrence Weiner, Daniel Buren, and Wolfgang Tillmans. It is an adventurous and wide-ranging collection overseen by Gene Jones, wife of Cowboys owner Jerry, largely made up of site-specific commissions. But why is it at the stadium? Part of the reason is aspirational, a desire to be seen as sophisticated even amid the brutality of football, driven by that inferiority complex and eternal hunger for external validation. Part of it is simply because the Joneses can. But putting a museum in a football stadium brings the art to people who would never set foot in a museum, speaking to Dallas’ mostly slept-on inclusivity. It works the other way, too: if they want to see the work, art snobs have to go to the football stadium.

34. My favorite place to go in downtown Dallas is the Chapel of Thanksgiving in Thanks-Giving Square. Designed by Philip Johnson, it is a delightfully incongruous structure, this little dollop of softserve ice cream amid the high-rises. Its ceiling contains Gabriel Loire’s Glory Window, a kaleidoscopic stained glass spiral glimpsed for a split second in Terrence Malick’s 2011 film, The Tree of Life.

35. Other directors have been drawn to Dallas: Robert Altman, David Byrne, Oliver Stone. Logan’s Run was made here. RoboCop, of course. Wes Anderson made his first film here, Bottle Rocket, co-written with Owen Wilson and featuring Wilson and his brothers Luke and Andrew. (The Wilson brothers were born and raised in Dallas, the sons of photographer Laura Wilson. Her career started when she was hired to assist the acclaimed fashion and portrait photographer Richard Avedon with his landmark In the American West project.)

36. David Lowery wasn’t drawn to Dallas. The director of last year’s The Green Knight was raised here. He could have left long ago, but he didn’t. Like Nowitzki and Badu, Lowery stayed. He and his wife, Augustine Frizzell (also a filmmaker, who directed the pilot for HBO’s Euphoria), bring the world to Dallas, having created a sort of commune of their own here, populated by various collaborators. It is no socialist utopia, but the people who came to La Réunion would recognize the impulse to create a haven of progressive thought.

37. Stone is probably the filmmaker from outside of Dallas most associated with the city. Between 1988 and 1991, he made three films there: Talk Radio, Born on the Fourth of July, and his messy, paranoid, maximalist masterpiece, JFK. For JFK, Stone filmed in Dealey Plaza. People have tried to reclaim the site since not long after Kennedy was killed there, when Dallas was saddled with the nickname the “City of Hate.” In the early 1960s, Dallas was home to General Edwin Walker, who appeared on a 1961 cover of Newsweek under the headline “Thunder on the Right,” making him the standard bearer for the conservative anti-communist movement. Walker joined other right-wing activists in Dallas, including oil magnate H. L. Hunt and Frank McGehee, founder of the hardline anti-communist organization the National Indignation Convention. The “City of Hate” moniker was unkind, but not entirely inaccurate.

38. Most recently, in late 2021, Dealey Plaza became home to an offshoot group of QAnon followers lured there by the promise that JFK – or his son, or maybe both – would come out of hiding and reveal himself/themselves as still among the living. Some of those followers thought JFK Jr. was in disguise as their leader, Q. Others thought Princess Diana would come back, too, some believing that the re-emergence would be timed to a Rolling Stones concert at the Cotton Bowl in early November. The Stones were the only ones to show up.

39. The best attempt to recontextualize Dealey Plaza or, at least, use its enduring power for good – or art – was the 2010 video for Badu’s “Window Seat.” She said she filmed the clip for the song there because “it was the most monumental place in Dallas I could think of.” Directed by Coodie & Chike, the duo behind the 2022 Kanye West documentary, the “Window Seat” video was filmed in one take, with no permits or permission. The clip featured the singer slowly stripping until she was completely nude, whereupon an unseen sniper shot her – representing “the kind of character assassination one would go through after showing his or herself completely,” Badu said. The quote undersells the video, though you could argue that Badu’s explanation alludes to how Dallas had to bear the weight of the “City of Hate” image for so long – and wrestle with the idea that there was more than a little truth to it. Perhaps Dallas had really shown itself completely that November day in 1963.

40. On another November day, this one in 2021, artist Alicia Eggert unveiled her neon and steel sculpture The Time for Becoming, commissioned by the Nasher Sculpture Center. Installed a block away from the museum, in a vacant lot on Ross Avenue, The Time for Becoming, like much of Eggert’s other work, takes the form of a sign. In bright red letters, two messages alternate:

NOW IS ONLY FOR THE TIME BEING

NOW IS ALWAYS THE TIME FOR BECOMING

Eggert’s piece is scheduled to remain there for one year. But its impact will last much longer, resounding an eternal truth about Dallas that, once witnessed, can’t be forgotten. It is always “the time for becoming” in a city in perpetual pursuit of an idealized tomorrow, so bent on looking ahead it doesn’t always see who or what is in the way, or even if something is really there.

41. So maybe the promise of La Réunion – the promise to build, not inhabit, utopia – was fulfilled after all. But those of Dallas and RoboCop were, too. All the fictional and hoped-for versions of this inhospitable place braid together to create a pop-up city on the prairie, where running toward an ideal – and not from the past – means you’re forever in the future.

Now is always the time for becoming.

Now is always the time for becoming.

Now is always the time for becoming.

The “Big D” is also known as the “Prison Ministry Capital of the World” in the Christian community, which is large in Dallas. So is the area’s incarcerated population: the state of Texas locks up a higher percentage of its people than any other democracy in the world. To say Dallas is a future blueprint is not to say the future bodes well. But maybe it does. In Genesis 41, Pharaoh lets Joseph out of prison. And at Genesis 41:41 Pharaoh gives Joseph control of Egypt. We’re not religious, but if 41 is about freedom, it’s also about research and creativity.

Credits

- Text: ZAC CRAIN

- Photography: TOBIAS ZIELONY

Related Content

Architecture Invented Italo-Disco

Architecture of Resistance: The Barricades of Kiev

“Once the Needle Goes In, It Never Comes Out”: LARRY CLARK on Sale in London

Stars Down to Earth: An Interview with Artist DAVID-JEREMIAH

DR. KATHARINE HAYHOE Doesn’t Want You To Panic

CALI THORNHILL DEWITT’s Sweatshirts “Pour One Out” for BIGGIE SMALLS, MASSIMO VIGNELLI, and ROMY SCHNIEDER

“If this is hell then I’m lucky.” In the Eye of the Storm, Listening to DJ SCREW

ETTORE SOTTSASS: The Master of “Bastard Design”

Countryside by REM KOOLHAAS (Part I)

Countryside by REM KOOLHAAS (Part II): Case Studies