Dozie Kanu: EVIL

In the 032c archive, we highlight the best pieces from over 20 years of printmaking. This print feature with Dozie Kanu by Claire Koron Elat was originally published in 032c Issue #43.

Artist Dozie Kanu’s practice is far from being mainstream, yet his work appeals to an audience beyond the traditional art world: “I want people from two far ends of the spectrum to engage with each other,” he says.

“The best examples within the space of music are Thom Yorke and Frank Ocean. They are people who make work that’s consumed by the masses, but you could also write a long essay about the complexity and innovation present in their work.” Working at the intersection of design and art, Kanu amalgamates the two sectors in an ever-multiplying category that makes the work accessible, creates an object you can relate to on a mundane level – as we are constantly surrounded by furniture. He investigates colonial histories, African diasporas, and hyper-contemporary pop culture phenomena through sculptures that are transformed into ancestral objects.

These sculptures weave together discarded and found objects that the artist sources mainly from the Portuguese countryside where he is currently based. Yet Kanu’s interests lie beyond the detritus of the past and present. As the New York Times reports, “Though his career has only just begun, Kanu envisions his as a generous practice – he is already thinking about inspiring the next generation.”

jacket, top, and pants BOTTEGA VENETA, shoes PRADA, accessories HATTON LABS

“I’m interested in glorifying something that we in the world would say doesn’t deserve being glorified.”

—Ed Ruscha

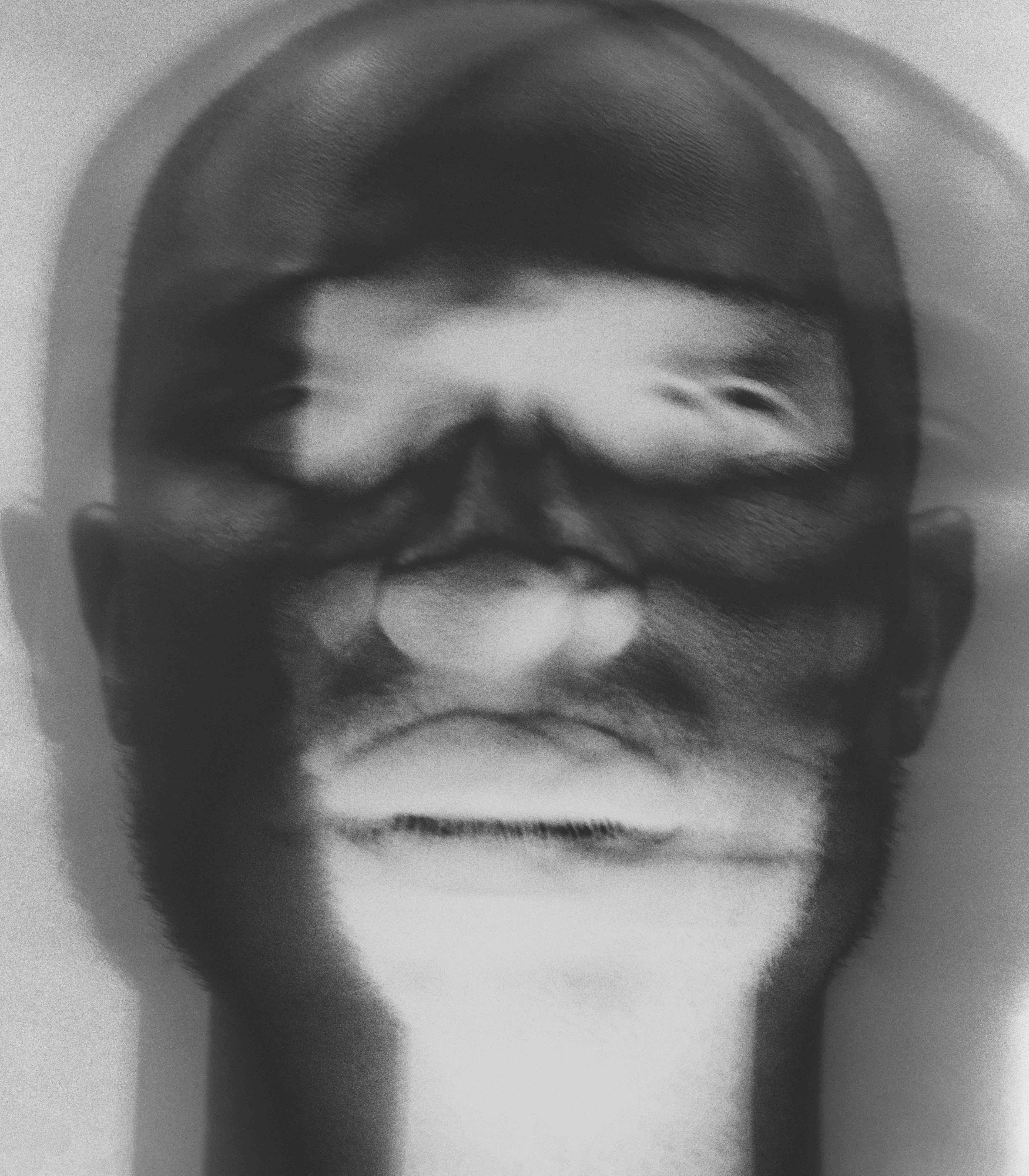

RIGHT: Dozie Kanu, Prediction, 2019. Courtesy the artist

I have two tattoos that show artworks by Ed Ruscha, but no one ever recognizes them: delicate lines that form “VERY” and “2.” They are references that often get lost or that are so absorbed by their ubiquitousness that they result in serene subtlety. The word “very” and the number 2 are so mundane that they are not seen as referential entities, which, in this case, belong to two artworks, Hurting the Word Radio #2 (1964) and Very (1973). But in general, Ruscha’s words and references to pop and consumer culture holler; they can be read and recognized precisely because they are normally so legible.

Dozie Kanu’s references, in contrast, belong to a sea of pacific subliminality. Even when he curated a Tumblr over seven consecutive days for Showstudio in 2018, he never explicitly revealed how he weaves his references into his sculpture. On the moodboard, he gathered images of paintings and sculptures by historic and contemporary artists, designer furniture, fashion collections, architecture projects, and photos of friends and family from his private collection. All this material informs the artist’s practice, which is mainly characterized by his sculptures reminiscent of furniture whose function has ostensibly been stripped.

LEFT: Dozie Kanu, Foremothers, 2019. Courtesy the artist

One of the items pinned on Kanu’s digital moodboard was Ruscha’s screen print Evil (1973). It depicts the word “EVIL,” in all caps and black, placed on a violent but seductive red background. Kanu is concerned with displaying such spiritual concepts and religious tropes in the physical world—often in relation to the Black body—and proceeding in an inconspicuous and implicit manner. The artist transfers or translates these political, religious, historical, and pop culture tropes into the materiality of his sculptures, which are then surrounded by an evocative atmosphere. In his exhibition “Blood Type” (2021) at Performance Space, New York, several stimuli from said moodboard merged into a red inundation. An ensemble of various ornamental stools with suggestive titles such as Student Loan Debt Relief (2019)—tinted in the same gloomy, red shade—was placed on a velvety red monochrome carpet that appeared to be a lake of blood. It is as if Kanu blended Ruscha together with the red of David Hammons’ African-American Flag (1991/2015), the red of Jean-Michel Basquiat’s Deaf (1984), and the red-dipped coat of Yohji Yamamoto’s Autumn/Winter-1999 collection—all references from his moodboard. Like Ruscha, Kanu also reveres things that others believe to be mundane. Even when he incorporates other artists and designers into his practice—also in a material form, such as in Healthy Minds Must Grow (2020), where he uses a found Dries van Noten hoodie—he contemporaneously physicalizes these allusions through banal found materials, including wheel rims, steel wire, or simple house paint.

jacket DIOR, pants BOTTEGA VENETA, top LANVIN

The installation three / four useless flagpoles playing with gaud (2022) consists of seven objects, including a chair, a vase, and what seems like a kind of rake. All objects function as the bases for flagstaffs with absent flags. If you are versed in Kanu’s latency, you might plant Hammons’ African-American Flag atop them. Or you might recognize the flagpoles as props that are arranged on a theater stage where an adaptation of Alberto Moravia’s Il disprezzo (1954), also included in Kanu’s Tumblr board,is being rehearsed. “It’s called biting when you’re taking someone else’s style and just co-opt [it], making money off something that was created by someone else. I always make sure that whenever I reference [others’ work,] I bring something completely else to it,” says Kanu.

jacket DIOR, pants BOTTEGA VENETA, top LANVIN

“Outrageously magical things happen when you mess around with a symbol.”

—David Hammons

LEFT: top and shoes KIKO KOSTADINOV, pants EMPORIO ARMANI

RIGHT: Dozie Kanu, 5 Star, 2019. Courtesy the artist

Before relocating to Portugal, Kanu studied production design for film in New York. “I had visions of becoming a film a director who makes film that are a hybrid between James Cameron and Spike Lee,” he tells me as we drive the hour from his studio in Santarém to Lisbon. Although he has shifted his artistic focus, his exhibitions often feel like stages. Not the kind of stage Cameron or Lee would occupy, though. Kanu’s is less grandiose, more delicate. “I was a soft-spoken person, but I still had a huge desire to create images,” he says. “I didn’t really have the technical competence to become a cinematographer.”

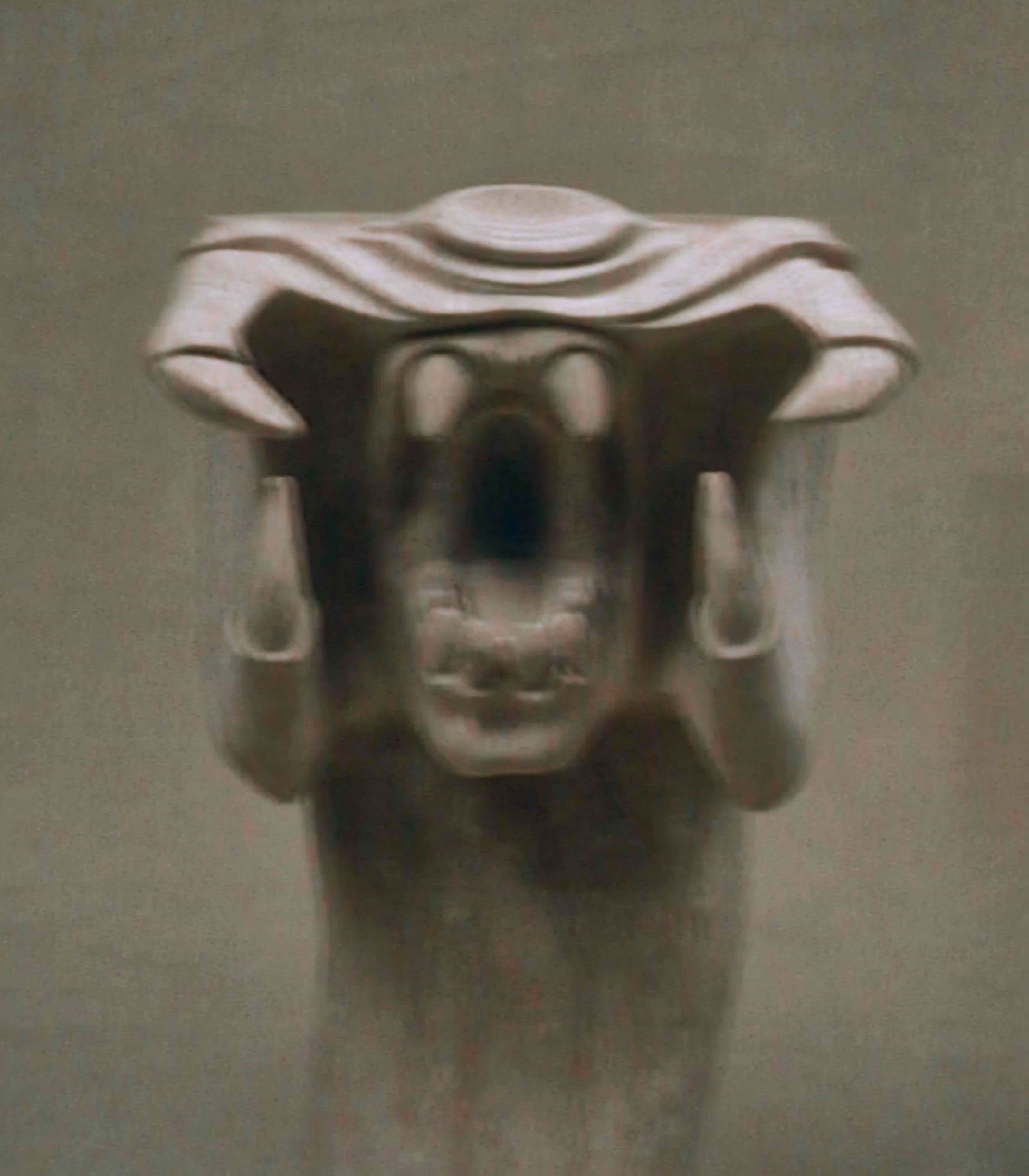

Raised by Nigerian immigrant parents, the artist’s upbringing in the conservative American state of Texas led him to negate his ancestral roots at first. With his maturing and the maturing of his work, he started to unearth his geographical family history and reclaim it. Kanu has since made several research trips to Nigeria as well as to other African countries, which have provided a plethora of themes and visual languages. He does not merely regard the beauty of African “sculpture” based on superficialities, however. Such “sculptures” were functional—that is, design—objects that have been misinterpreted by the doctrinarian Western gaze as artifacts that should be contemplated or that function as ornaments. Kanu’s sculptures intend to disrupt this established belief and dissolve Eurocentric systems of logic.

top MAISON MARGIELA, accessories HATTON LABS, DIOR

Another research interest of his is the fraught relationship between Africa and the West. “A lot of people don’t know that Portugal was one of the first colonizers and basically started the Transatlantic Slave Trade,” Kanu says about his current adopted country. In 1526, Portugal operated the first transatlantic voyage to transport people from the Coast of Africa to slavery in Brazil, and thereby set an example for other European colonial powers. The title of Kanu’s show “ARS JUX PAX” (2019), at Salon 94, for example, borrows the graphic ensign of The Royal Niger Company, a trading corporation that was active from 1879 to1900 and that was fundamental tothe formation of colonial Nigeria. The artist thereby addresses unethical trade practices of the past that still reverberate in the present.

RIGHT: Dozie Kanu, Beltway 8. Courtesy the artist

Kanu’s concerns reach beyond the political issues of his current home. Chair [ v ] (Electric Chair) (2018) is a marble seat whose structure is reminiscent of a Christian cross and that has brown leather belts affixed to the back. The sculpture refers to the practice of capital punishment, specifically in Texas—the state with the highest execution rate in the US. Yet, countless reports affirm that there is a pervasive and endemic racial prejudice in the application of the death penalty in all 27 states that still practice capital punishment. According to the Death Penalty Information Center, “When executions have been carried out exclusively for murder, 75 percent of the cases involve the murder of white victims, even though Black and white [people] are equally likely to be victims of murder.” Several other studies that establish the same conclusion show the enduring influence of race on a social, political, legal, and structural level, which is rooted in colonialism.

LEFT: Dozie Kanu, Untitled. Courtesy the artist

As an attempt to reconfigure the inferiorizing bond with colonial empires that have oppressed people, Kanu materializes these complexities around collective Black pain, which innately imbues his work with tension. It is obliquely charged with the evil history of colonialism and structural racisms, whose traces are still broadly visible today—which is why it is incorrect to deem both as history. Yet Kanu’s work is not specific to Portugal, the US, the place where the artist’s material was found, or the place it alludes to; Kanu instead proposes a universal material language.

"What I remember is the stone banister of the grand staircase at the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston. I remember wanting to climb on it, I remember climbing on it …. I didn’t understand until later that this was not permitted.”

—Gordon Hall

Kanu’s studio in Santarém is an old warehouse, which he refurbished himself, combining work and living space. You enter the first space, where he stores discarded wood panels, quaint objects from antiquity shops, raptor spikes, metal containers, and automotive parts, among others. His studio smells burnt in a comforting way, like a warm spring day shortly before sunset. Situated in a romantic landscape, the studio is surrounded by a couple of other houses but is essentially far away from the buzz you would experience in his former New York base. “I didn’t want to have a gallerist in my ear anymore who tells me to make another edition of this piece,” Kanu says as we walk through the studio’s vast space, which is cluttered like the references he uses in his works. Outside his car is parked. He uses it to drive to Lisbon sometimes, where an art scene more bustling than in Santarém, with its antiquity dealers and old ceramists, exists. The isolation he now experiences over extended periods in Portugal allows him to produce work that stays separate from market determinants and the social aspects stemming from the artist’s milieu.

Dozie Kanu, Bhad (Their Newborn’s Crib), 2019. Courtesy the artist

Growing up in Texas, Kanu was the childhood friend of Travis Scott. While this relation to Scott is not necessarily relevant to Kanu’s practice, it still embeds him in a particular social context close to celebrity cultures, which is ineluctably beneficial to the work, despite not determining its substance. “I hate being compared to other people. Early on, I was compared to Virgil Abloh in an article. That caused me to keep him at an arm’s distance because I didn’t just want to be labelled as one of his understudies. I assumed there would be more time for me to establish myself first—carve our my own lane, and then we would become homes.” It is a sphere Kanu intends to distance himself from, as it is largely decoupled in its lifestyle and values.

In Kanu’s living space, which is a minimalist concrete room, I find an early 032c issue. As we discuss the changing editorial landscape, he mentions that he once published a single issue of his own publication, 00 Magazine Magazine, as an excuse to produce a fashion editorial. In the editorial note, he writes, “Within thinking about what the function of a commercial magazine is or the cultural production that magazine editors imagine, it felt appropriate to sidestep commercial interests and use every aspect of the magazine’s content as a space for poetry.” Talking—or writing—about the function of a magazine in a magazine, might be comparable to meditating on the function of design and art objects through such objects. To escape functionalisms that curb burgeoning potentialities, the work has to be engaged with multiple matters and carry different meanings.

“Design has to work. Art does not.”

—Donald Judd

Donald Judd’s 1970s bedroom on the fifth floor of 101 Spring Street, New York, featured a bed he built, a simple platform made of wooden boards with a mattress on top. In 1977 Judd moved to Texas, seeking open spaces where he could show permanent installations. There, he was disenchanted by the available furnishings, as there were only either fake antiques or tacky plastic kitchen furniture with nitwitted patterns and flowers. Although he had already designed furniture in the early 1970s, he returned to this practice in Texas out of necessity. Although he was both an artist and a designer, he distinguished between the two realms: “The furniture is furniture and is only art in that architecture, ceramics, textiles, and many things are art,” acknowledging that design objects by artists will always be influenced by their creators’ artistic practices.

The first time I met Kanu was during last year’s Art Basel Miami. We had coffee at the Faena with two gallerists from Chicago, whose work is at the intersection of art and design. After years of participating in Design Miami, they had decided to stop because of the audience’s disrespect toward the intellectual value of the works. Not knowing much about the design world, I was stunned to hear about the climate at design fairs: people run into objects, toss them on the floor to test their durability, ask for the work to be made in a different color, and relentlessly touch everything with greasy fingers from the club sandwich they just bought for 25 dollars (before tax) at the fair’s bar. That day, Kanu told me he had initially situated himself in design instead of the art world, but in nowadays he says that he was thrown into it: “I started to get invited to more major shows when I was relatively young. One group show in 2017 at Salon 94 in particular—where I was showing alongside some artists that I had only seen in blue chip galleries before, such as Vito Acconci and Carol Bove—gave me the confidence to say, ‘Okay, I can do this. This is a stepping stone.’ Scott Burton was in that show, too, and he was one of my heroes.” The fact that he now places his work predominantly in an art context might look like a narrowing of his practice, but doing so actually expanded it, like the wide sea of subliminalities he swims in: “I got pigeonholed pretty early on as a designer. I was just happy to support myself financially. But then I started to see that things were getting lost.

Credits

- Text: CLAIRE KORON ELAT

- Photography: CASPER SEJERSEN

- Fashion: ELLIE GRACE CUMMING

- Talent: DOZIE KANU

- Hair: AMIDAT GIWA

- Make-up: MEE KEE

- Lighting Designer: SCOTT BRICKETT

- Producer: LAURE L'OR

- Photography Assistant: ARIEL MIHÁLY

- Photography Assistant: JOE PETINI

- First Fashion Assistant: ISABELLA KAVANAGH

- Second Fashion Assistant: MONI JIANG

- Digital Operator: LARRY GORMAN

- Post Production: SHE POST PRODUCTION