R.I.P. Germain: What Comes After God?

|Harriet Shepherd

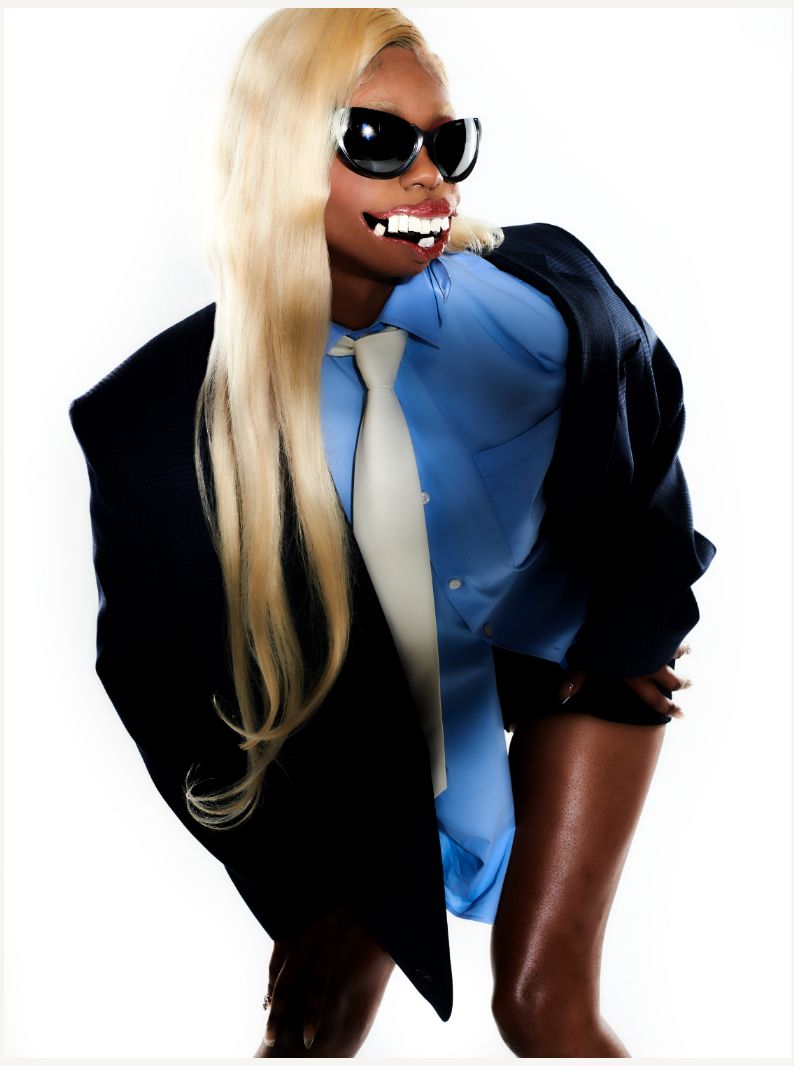

R.I.P. Germain unpicks and analyzes hyper-objects of Black culture, their complex logic of cultural gatekeeping, and the (mis)perception of these dynamics in a wider (white) world.

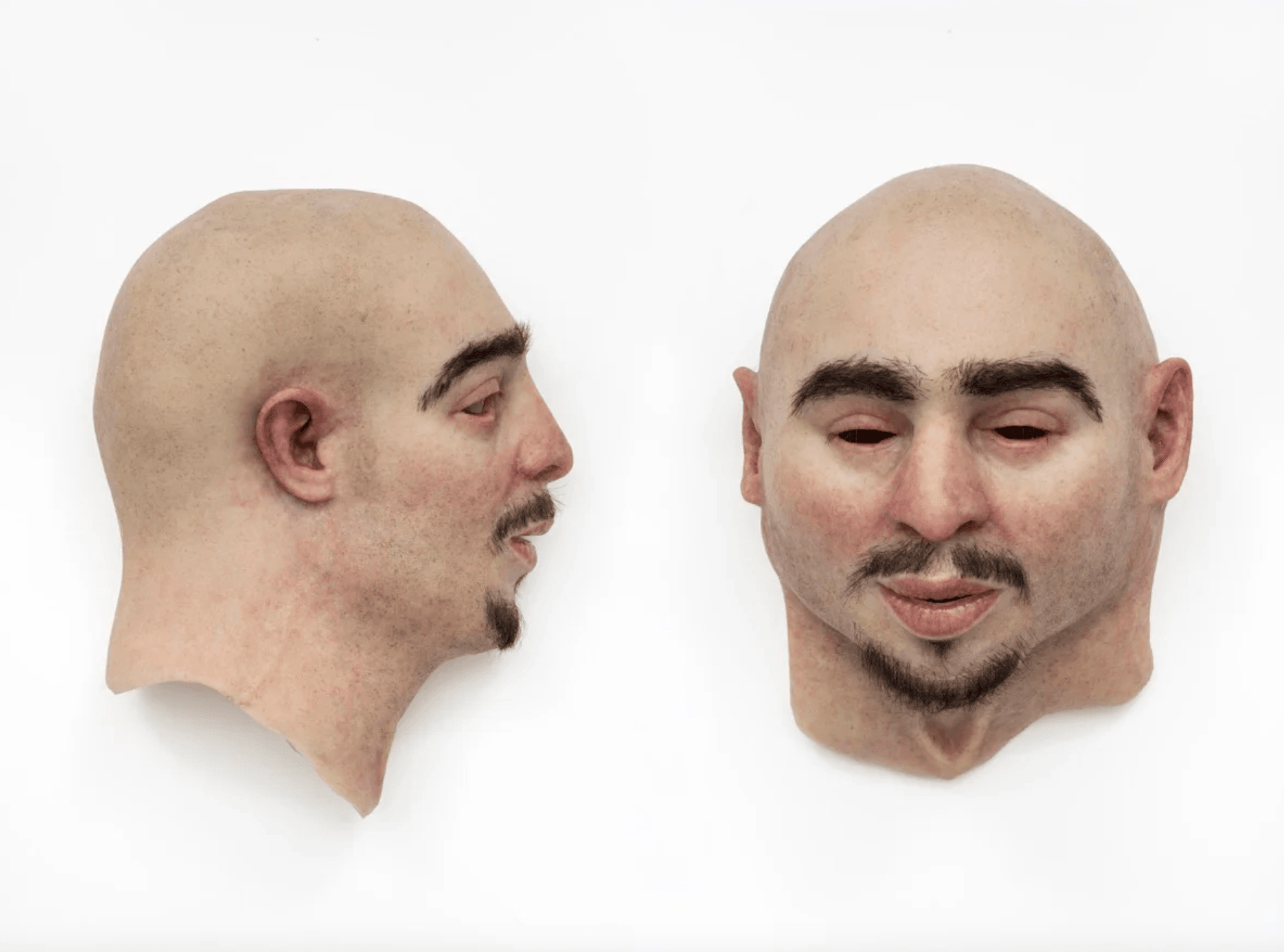

A few months after being released from prison, Manchester-born rap artist Tunde dropped the video for his bread-counting comeback, Loaf Man. In its 3.3 million-viewed Youtube video, a four second sequence shows a gloved hand greasing up a brick adorned with Thomas Muller’s face. It’s an image that artist R.I.P. Germain returns to frequently.

To the Luton-born artist, now based between London and LA, Tunde’s reference rings as clear as his lyrics—an obvious depiction of the drug-smuggling method deployed to bypass sniffer dogs. But it’s come to epitomize the artist’s exploration of the overt versus covert and the unspoken languages we use to read the world around us. In lectures, R.I.P. Germain asks art students to explain the sequence, and more often than not, they miss its meaning. “The image is subtle if you don’t know the codes,” he explains. “The fact is, you can have a completely different experience to someone if you’re equipped with those behavioral and social cues.”

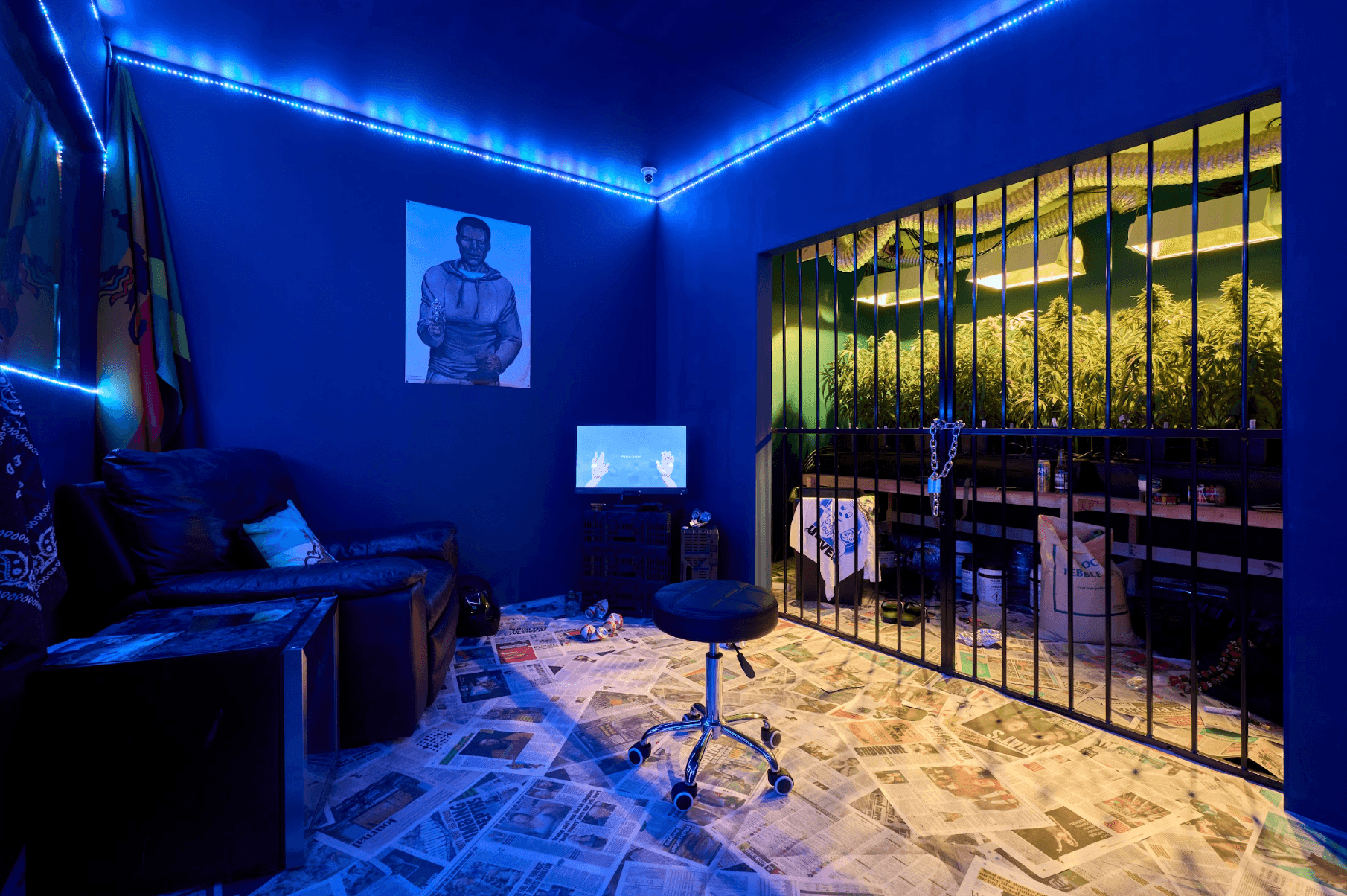

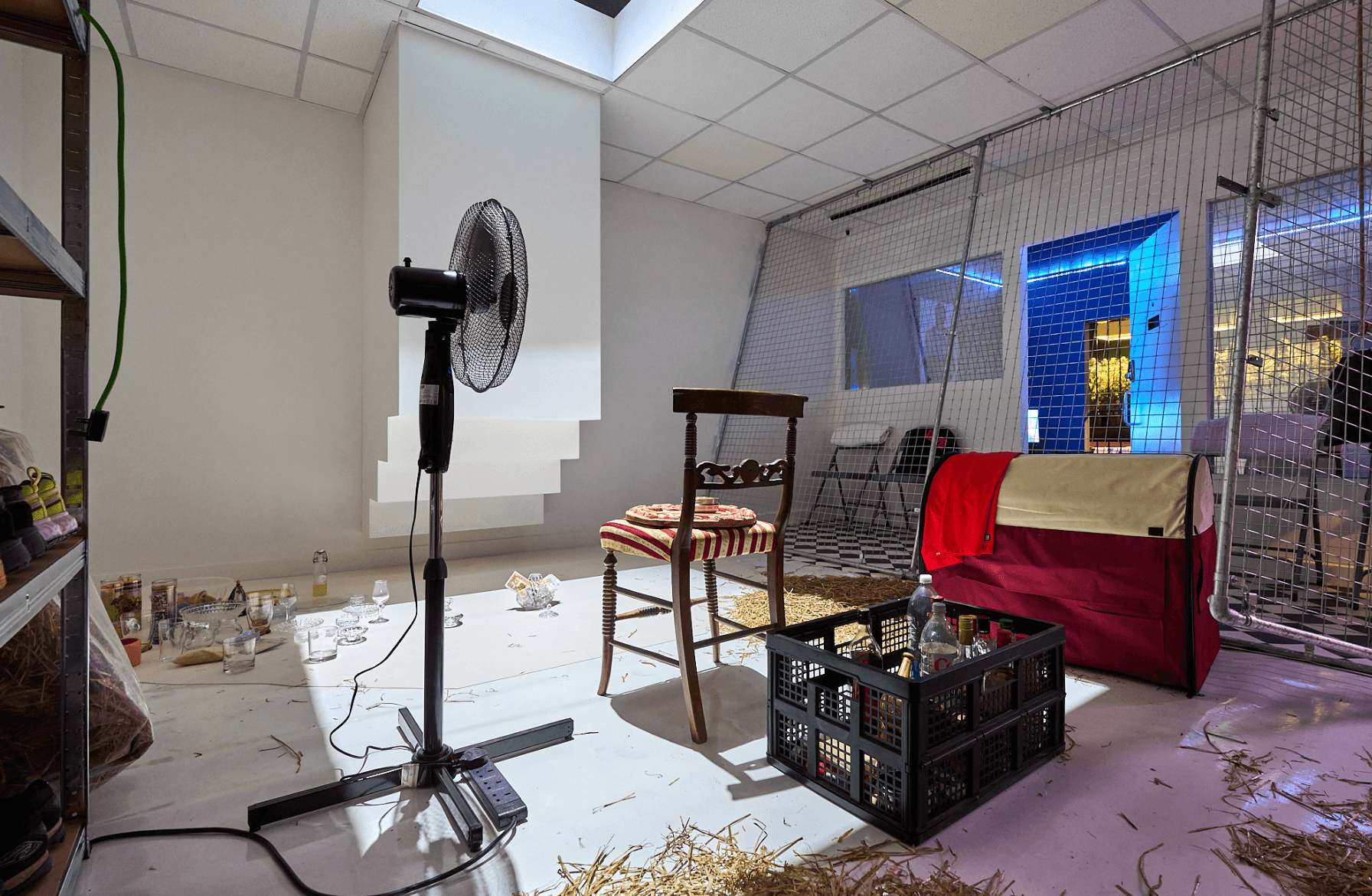

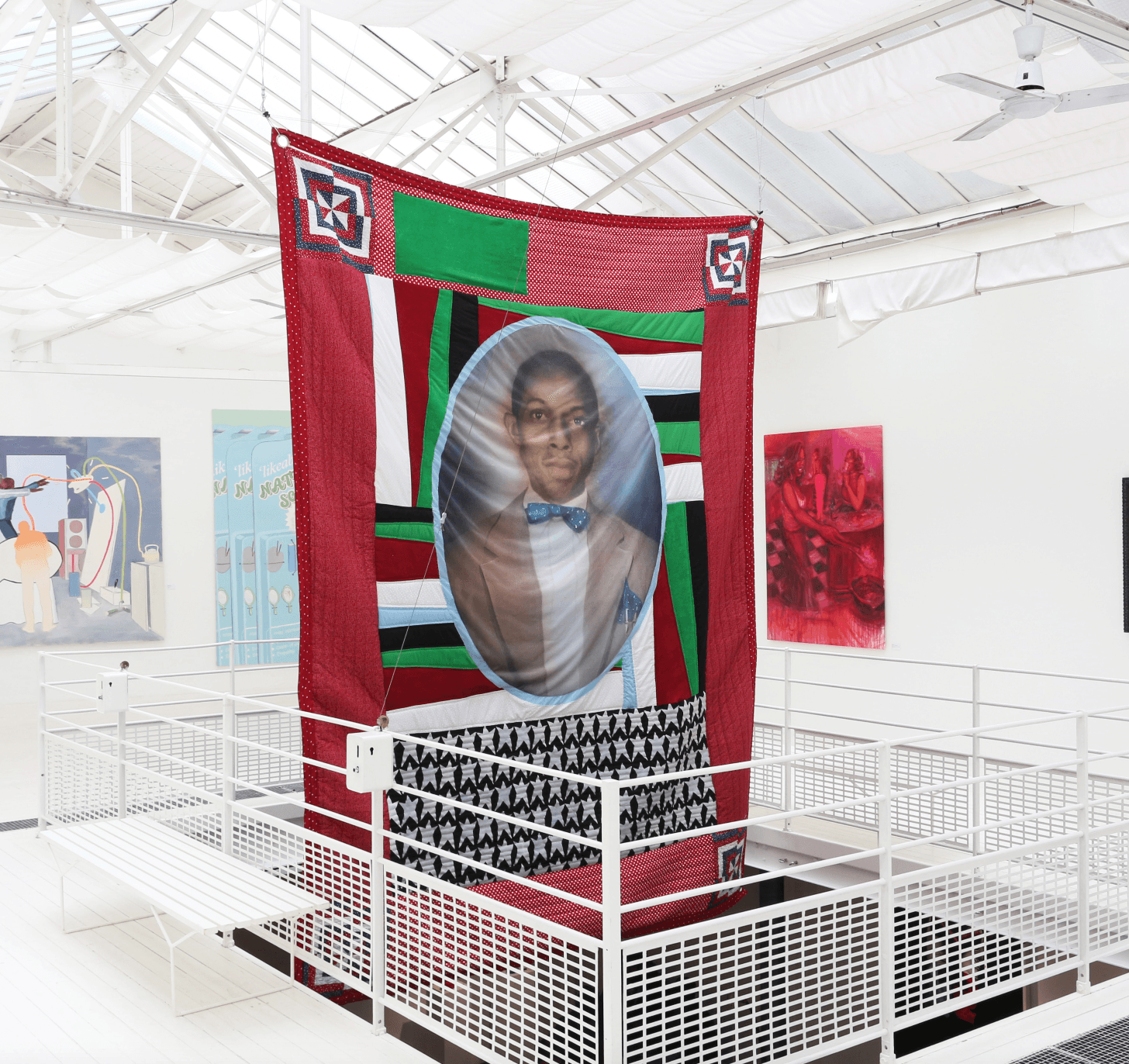

It’s these same kinds of cultural codes that underpin R.I.P. Germain’s current exhibition, “After GOD, Dudus Comes Next!”, currently on display at FACT in Liverpool until October 13. Building on last year’s ICA show, R.I.P. Germain’s latest work doubles down on the concept of false fronts—spaces that may seem innocuous but serve hidden purposes, inaccessible to the uninitiated. Within the gallery, R.I.P. Germain constructs a streetscape featuring three such spaces, each full of coded objects that reveal or conceal their true nature depending on the viewer's background and cultural understanding.

Visitors enter a Hatton Garden-style jewelers, showcasing a diamond-encrusted Jesus piece of a white Tupac, and a nine-screen display of UK drill videos on mute. The space then morphs into a labyrinth of urban relics: a nightclub under refurbishment flaunts neon camel and fire signs, while a stripper pole and sleeping bag inside a disheveled kebab shop suggest a hidden history of varied uses. Behind mirrored sliding doors, a clandestine weed café is strewn with bottle crates and cowrie shells, and shrouded with the scent of marijuana. Across the exhibition, hundreds of these seemingly mundane objects and symbols suggest a world of illicit activity, ritual, and aspiration—the meaning you derive from them depends on your prior experience. If you know, you know.

Toying with the tension between monetary and cultural currency, R.I.P. Germain’s work engages with difficult truths, without spoon-feeding easy answers. It has opened up institutions like the ICA to those for whom “buss down” and “gucci link” (terms from the exhibition’s glossary) need not be explained. And opening the same day Britain bid farewell to the same conservative government responsible for aggravating many of the issues it confronts, “After GOD, Dudus Comes Next!” is imbued with a confronting sense of urgency. Here, Germain reflects on notions of survival and success in a world obsessed with both spectacle and substance.

HARRIET SHEPHERD: There’s a kind of eeriness to stepping into a space marked by traces of absent life. It feels almost intrusive—like entering into a crime scene or stepping into a deceased relative’s apartment to sift through their belongings. Each item suddenly becomes imbued with a deeper significance of the person that was there before…

R.I.P. GERMAIN: That’s interesting, especially the intrusion aspect because you are entering someone else’s space. The intrusion is real because I’m commenting on worlds I’m not wholly involved in, but ones I try to give the respect and reverence they deserve. The items are not placed flippantly; they reflect real worlds I’ve seen. The spaces are hybrids and amalgamations, all molded into a singular expression of these types of spaces. I’ve been into dozens of bandos, trap houses, cafés all across the world… The aspect of it feeling like a crime scene I get, I totally get why people would feel like that, but that isn’t necessarily my intention. As an artist, I don’t put my feelings or expressions on a higher pedestal than those of the audience.

HS: Your process—visiting all those spaces—feels a little bit like investigative journalism: you’re adopting an alter ego, allowing people to project stereotypes on you, becoming that character, and interrogating that world. That requires a lot of confidence and curiosity. Where does that stem from? You’ve said you consider yourself to be a painter at heart...

RG: I didn’t know if I was going to be good at it. It does take a lot of courage and confidence, but to me, there was no other option. You can’t half-ass this stuff. The methodology that comes with my work is: if I have an idea or an interest in making a specific type of work, I’ll then try and think about what’s the best way to express that. This work started off with the jewelers and rap culture. Growing up watching music videos I was attuned to people flashing jewelry—50 had his G-Unit spinner chain, Biggie had the two Jesus pieces, Fabolous had his versions of that. There were all these iconic expressions of wealth.

The ICA show presented me with an opportunity where I might have a little bit of budget to make some type of jewelry. So I jumped on that. I wanted to see behind the curtain. A Jewelers showed me their VIP room because they assumed I was a rapper or footballer. I am of the ‘culture’, I am a product of it, and I carried myself in a certain way. My knowledge of Orisha comes from being involved in a community in Trinidad when making a film [mew] for the ICA. With the illegal drug production side of things, it was just growing up around family and friends involved in those lifestyles, and frequenting those places in my regular life. You have to be part of those worlds to some degree because a lot of it is a one-and-done type of experience. If you “fail” at gaining access to these places, they’ll remember your face and they'll mark you out.

The way I’ve leaned into stereotypes is by foreseeing how I'm going to be read within a specific space, and using that as a strategy for survival or prosperity. When I'm perceived as a rapper or footballer, that's considered a positive stereotype by some. But I don’t believe in positive stereotypes; it’s still a reductive idea placed on me. Recognizing that and being self-aware of how I'm seen in specific scenarios, I figure out what I want from the situation and manipulate the experience to get what I want. It's not about giving the other person what they want.

HS: Using it without succumbing to it.

RG: Exactly. I’m using it as a tool without absconding my integrity. If someone is disrespectful, I don’t give a fuck what I’m trying to get out of it, I’m putting a stop to that straight away. It’s about recognizing how I’m read and using that as a tool against those who project it onto me.

HS: You mentioned on Instagram that you felt that you hadn’t quite stretched your muscles with this body of work and that this was a second chance to breathe life into it. What has evolved in this new context?

RG: For the ICA show last year, we were stretched in all realms—time, resources, etc. There were ideas that had to be left on the cutting room floor, and little touches that I wanted that just weren’t feasible. Being able to repurpose what had already been fabricated meant that there was sort of a leg up: there was already a foundation. It gave me the space to then fill in all the blanks. It’s the details that leave the biggest marks, you know—the figurine in the corner, some of the Orisha-orientated items—it’s those little things that actually formulate the world for the audience. It's like entering a bedroom: you notice the toys, the stereo, the posters—not the wall color or ceiling height.

For this show, the details establish the atmosphere. I imagine how the audience feels in the space, the messages and tone I want to convey. I have that poster of the Black male shooting target in the room. It’s very foreboding. And if you know the history of that shooting target, it adds even a more sinister tone. [The shooting targets were commissioned by Belgian police and used in police training departments across Belgium, France, and the US.] The artist—Malik [William Tai]—produced a lot of targets of very specific types of people, of all divisions, all types, creeds and such. But they’re quite intense.

This target actually looks like myself. So the idea of placing that in the grow room is a circulatory point. It’s a symbol that describes everything that is in this room—the idea of young Black males feeling like targets within society; how scrutinized the Black male body is, and how much of a commodity it is. There's a different type of value system placed on it. That type of methodology is applied to all the objects that are in the show, all of them.

HS: The work is also very sensory. You’ve worked with perfumer Ezra-Lloyd Jackson to create scents, replicating the smell of money, and weed, but also more abstract ideas, like the smell of success. What’s the recipe…?

RG: [Laughs]. That’s the secret sauce! I can’t divulge—I’m sorry to disappoint.

HS: What’s the starting point for thinking about scents that are more intangible?

RG: Basically, we conceptually think about success. What does success mean? Work... which leads to sweat... which is a tangible smell. Success might look like cars, so we think about fresh leather or petrol. It’s about what that term means on a personal level, but also how society deems success. We then talk about what smells are agreeable and work together, and through trial and error, create a scent that embodies these ideas. Ezra is a genius—he’s very good at smelling something and then breaking down the biomechanics of it, and replicating whatever it is you’re looking for.

HS: You’ve previously created a scent that attempted to evoke a sense of empathy—it’s a challenging effort in a world oversaturated with stimuli. What other strategies do you employ to pierce through desensitization?

RG: I start off with the basis of not treating the audience like idiots, or like they’re not capable of elastic thinking or dynamic ways of processing information. I’m not trying to curate a specific narrative for them to follow in a linear way, I’ve given them the space to just receive the work and think for themselves. And relatability is a big bridge to someone becoming empathetic to an issue or situation. Especially with young folk and something like UK drill being sort of the Zeitgeist music of their generation. It’s an olive branch of relatability in the sense of like: let me talk to you about my ideas about how society is structured through a language that you at least understand on some general level. I’m trying to get people to be more expansive in how they see society and this country and how the world works at large.

HS: UK drill videos feature prominently—though silently—in this work. I was listening to a recent podcast that mentioned a Carns Hill interview from 2017—he was talking about how, unlike a lot of US trap, UK drill interrogated issues and hardships, without glamorizing them. With productions skyrocketing since then, do you think the same can be said for now?

RG: The amount of wealth that’s pumped into these productions—Hype Williams could never have dreamed of some of these videos. It’s a victim of capitalism; UK drill is big business now. You get funding if you have a product that can be sold. But it seems to be at this tipping point where the vast majority of artists have either passed on or been locked up. So for me, there’s this real sense of trying to survey the land and assess the damage, like after some sort of cataclysmic event has happened. I've spent five years making work about UK drill, trying to throw up this red flag, like we need to be paying attention to this before it's too late. We already saw what happened with the grime scene, so let’s jump ahead of this before we’re five years down the line and going: oh, what a shame.

HS: Your work often addresses hypocrisies and double standards in society. You mentioned mew earlier [the 2022 film exploring syncretic religious tradition in Trinidad]. Spirituality is perceived almost as a taboo by white Western society—often dismissed or disparaged as “mumbo jumbo”—in itself a racist term used to denigrate or dehumanize African spirituality. It’s often seen as the antithesis of “progressive” societies and positioned in opposition to science and logic. But then you look to some of the most scientific and technologically advanced societies—Japan, China, Korea—and Buddhism, folk religion, and spirituality completely co-exist…

RG: Those types of communities [like the one in Trinidad] have spent hundreds of years being defamed, persecuted, and having their histories and cultures used as a tool to beat them with. Western European society has bastardized their culture. One lady in Trinidad told me about her auntie cleaning a room with cobwebs. She stopped her, saying, “That’s a spider’s home. We need to be respectful of that.” It’s not just hot air; they live what they talk about. Spending time with them made me realize how much power has been stripped from Black folks—in a sense of just having our own culture, religions, you know, knowledge of self stripped from us in quite a violent way.

HS: You’ve incorporated Orisha objects into this work too. [Like cowrie shells, used to consult the divine, assess spiritual alignment, and manifest the desired life.]

RG: And if you know the specific histories of each of these items, the show becomes something else to you. One guy said he was quite disturbed by the space, because it reminded him of crack houses he’d been in as a social worker, and that gave him a lot of PTSD. He spoke of one lady who was using those same kinds of Orisha items to pray for a better future because of the mess that she was in. I've had a lot of friends saying that they can’t go into the grow rooms just because of stuff that they’ve gone through in the past—it hits them a bit too harshly.

HS: That’s an interesting dichotomy—that in making the rigid art space more accessible and familiar, you might also be making it more triggering.

RG: The main sort of line that I walk along when making works like this, is that real is real. I'm not trying to dilute these spaces. They are as advertised. I'm not holding any punches, but in the same breath, I’m not trying to be reckless. I'm trying to speak about real stuff, but always thinking about what is the most respectful way of bringing these spaces to life that doesn't denigrate people that have been involved in this lifestyle.

HS: And similarly you might alienate the “traditional” art audience. That’s also an important uncomfortability.

RG: And that's the complexity also of the marginalized person you know. People who are, I guess, non-PoC are feeling a bit ostracized by the space. It’s like: yeah mate, we experience that near enough every day—especially in the art space. You can do this little bit of legwork in trying to understand the work, in the same way as we have to do that with other cultures. A person who has migrated is expected to learn the law of the land, read the social cues, learn social adaptability. It’s the same thing that I'm requesting of an art audience.

*This interview has been edited and condensed for length and clarity.

Credits

- Text: Harriet Shepherd

Related Content

Ice Cold: Jewelry as Political Embodiments

Water of the Womb: Joe Freshgoods x New Balance

Editorial Roundtable: EMMANUEL BALOGUN and KK OBI, visionaries of Boy.Brother.Friend

Resurrecting an Airline: Air Afrique

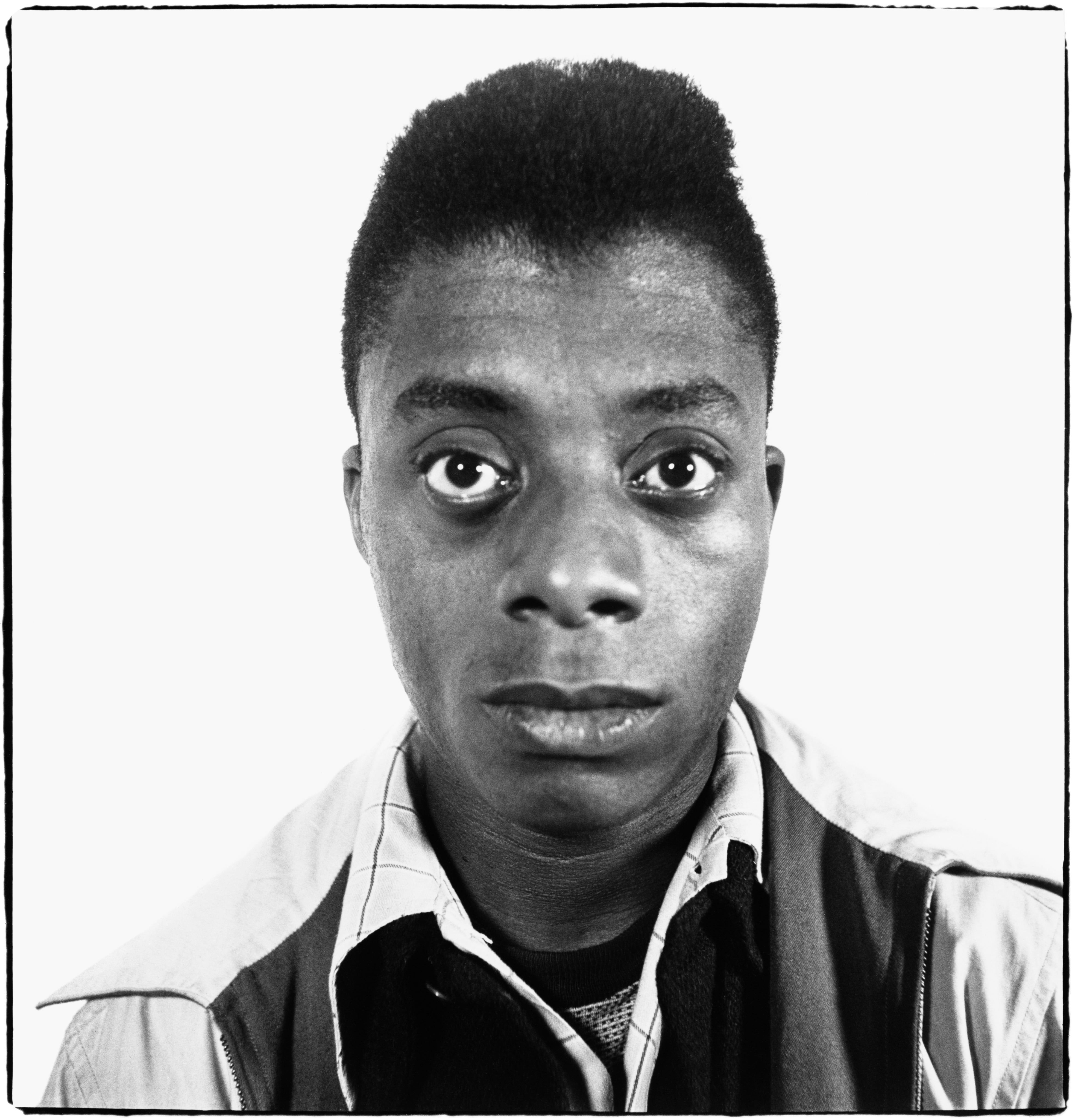

Reality TV as a Sociological Analysis: JAMES BANTONE

The Politics of Beauty: Tyler Mitchell

NO BLOODLESS PROPHET: Hilton Als on James Baldwin’s Body