NO BLOODLESS PROPHET: Hilton Als on James Baldwin’s Body

|Victoria Camblin

The body in the mirror forces me to turn and face it. And I look at my body, which is under sentence of death. It is lean, hard, and cold, the incarnation of a mystery. And I do not know what moves in this body, what this body is searching. It is trapped in my mirror as it is trapped in time and it hurries toward revelation.

James Baldwin, GIOVANNI'S ROOM

The winter issue of 032c deals with how we inhabit our material lives: how we acquire and assign value to our possessions, how we use them to realize and communicate our selves or our progress, how we preserve, monetize, and share them. The magazine’s cover dossier considers the “things” that author and social critic James Baldwin left behind in the south of France when he died in 1987 – an archive of books, clothing, art, and household objects that bears witness to their owner’s domestic life, his gay life, his aestheticism, and his appetites.

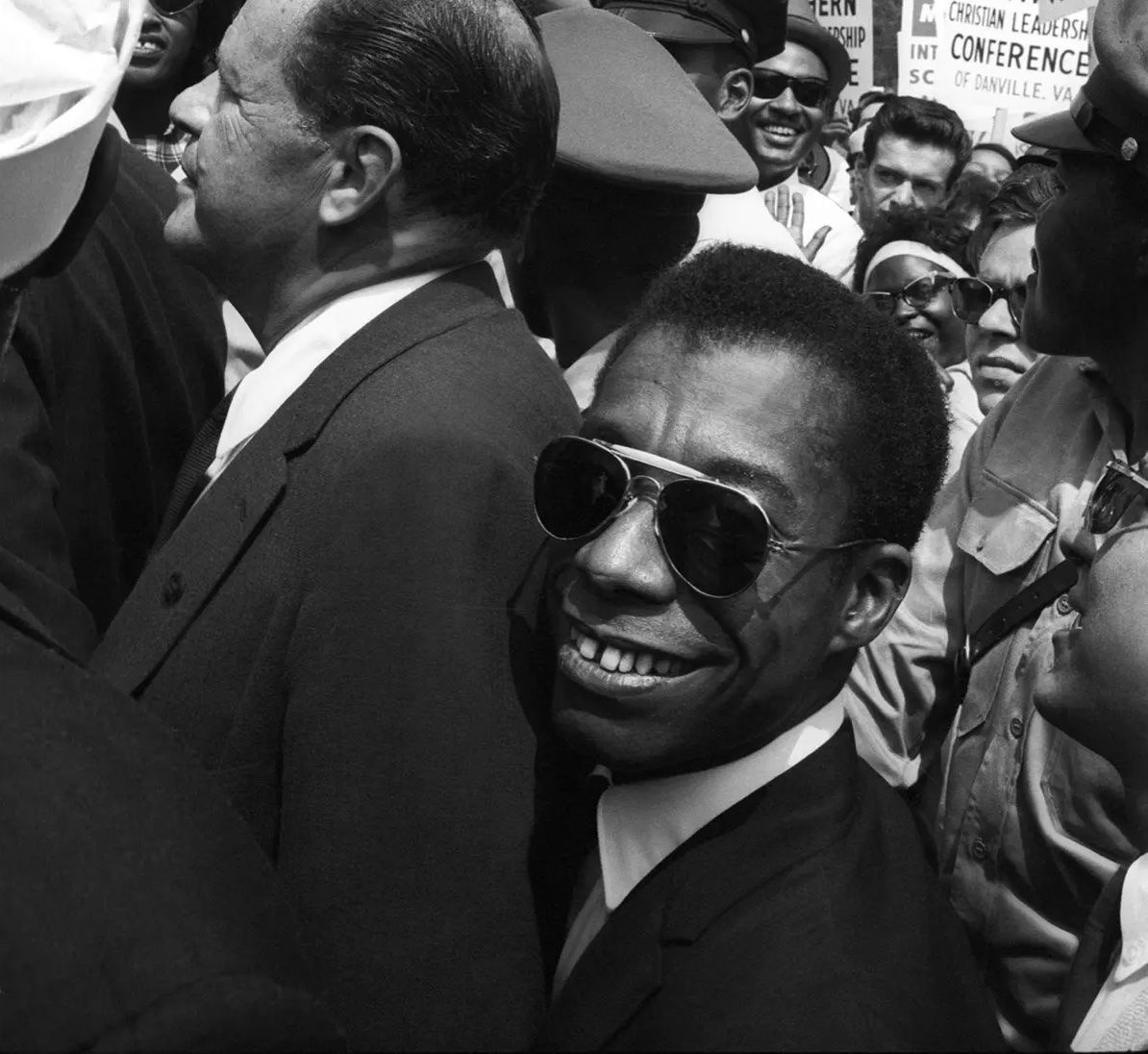

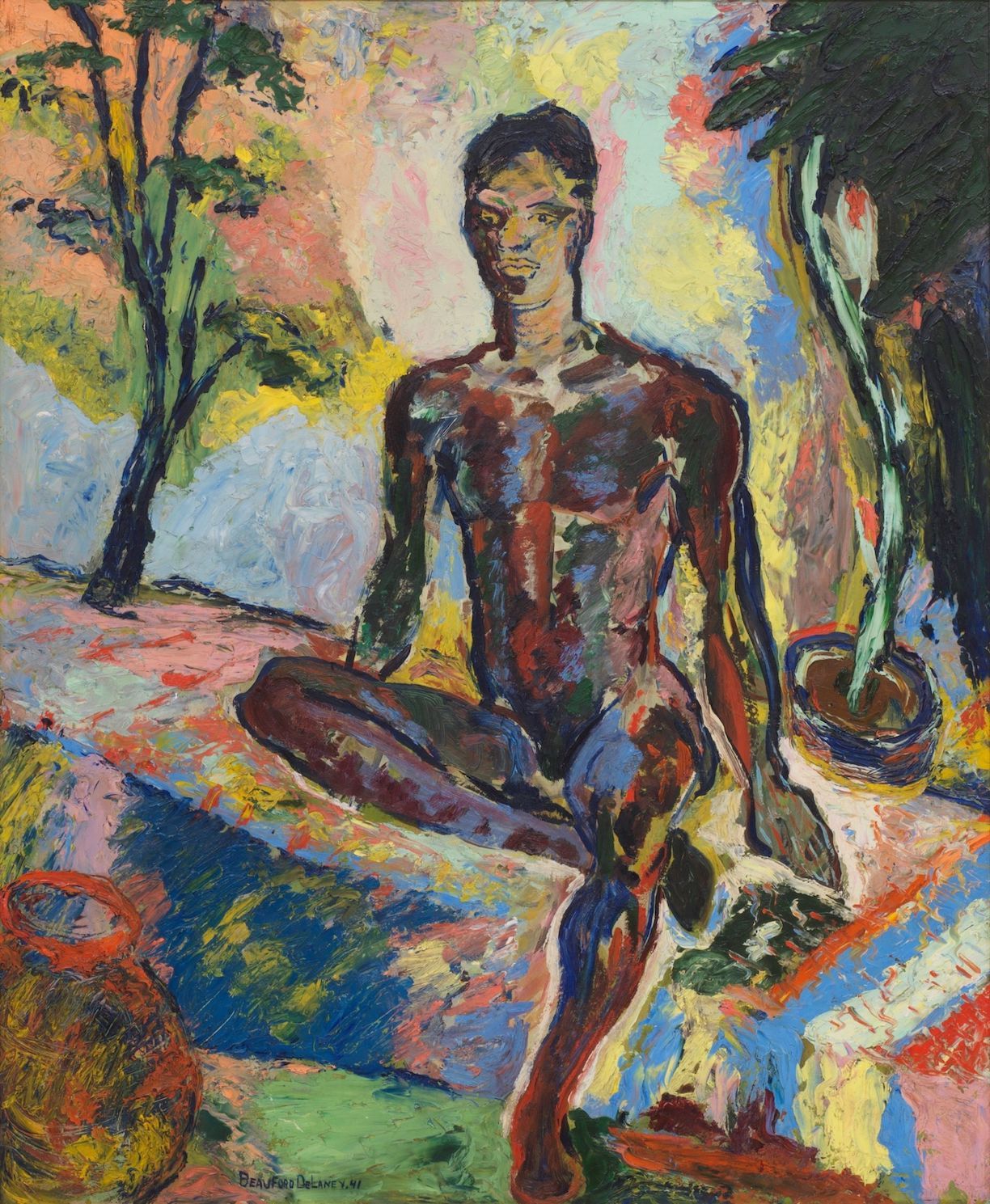

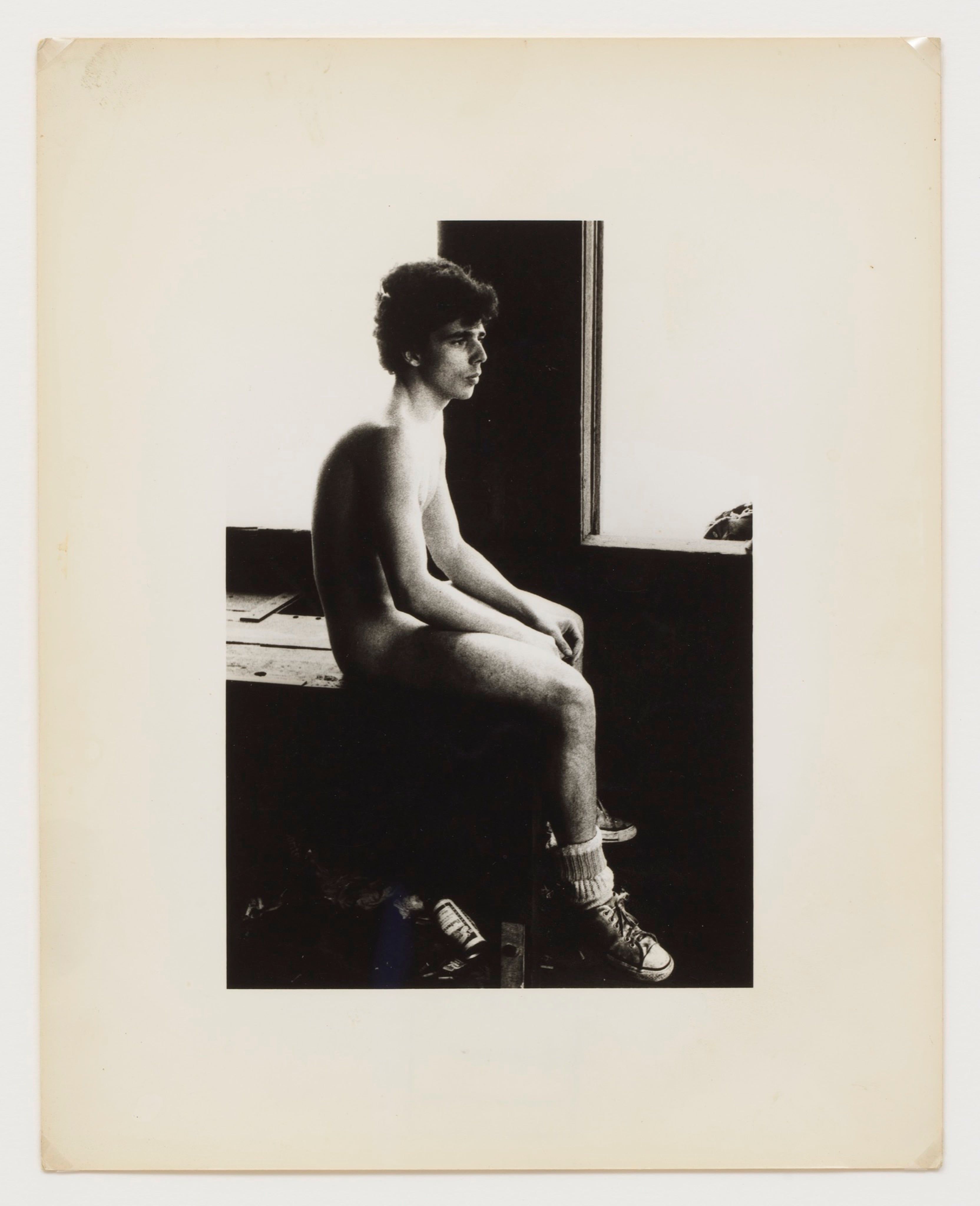

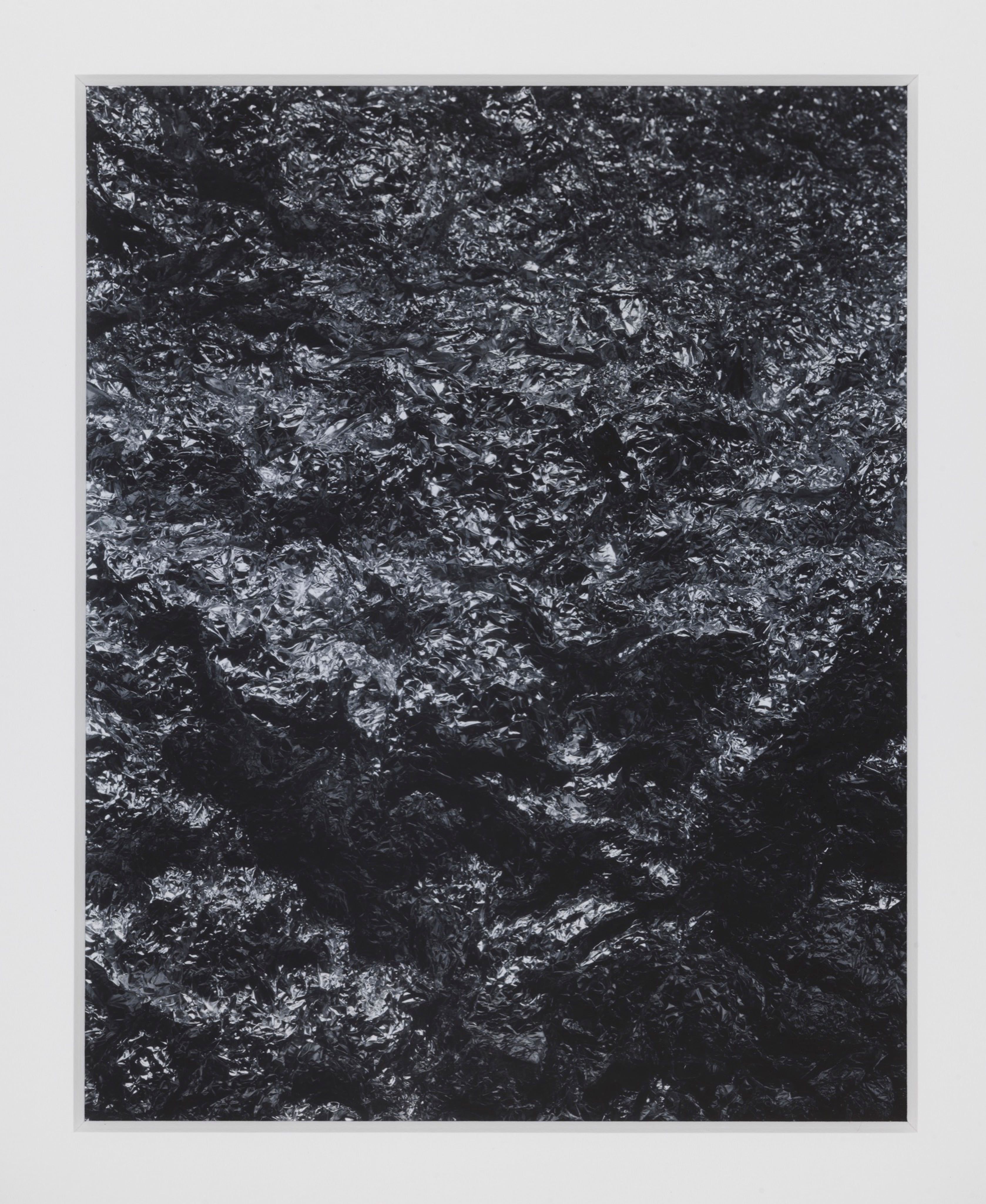

Baldwin’s belongings have yet to find an institutional home – they’re in storage, somewhere in Provence. But across the Atlantic, in his native New York, the late writer’s physical footprint is explored and expanded upon in “God Made My Face: A Collective Portrait of James Baldwin,” recently opened at David Zwirner. Curated by Hilton Als, writer and theater critic for The New Yorker, the group exhibition features work by artists including Diane Arbus, Richard Avedon, Alvin Baltrop, Beauford Delaney, Marlene Dumas, Glenn Ligon, Kara Walker, Alice Neel, and James Welling, displayed alongside rarely seen archival intimacies – letters, sketches, and even a song recorded by Baldwin.

Als, who contributed an essay to 032c’s Rei Kawakubo issue (Winter 2010/2011), has curated before. His “Alice Neel: Uptown” debuted at David Zwirner in 2017, presenting five decades’ worth of paintings and drawings portraying the people of 20th century Upper Manhattan. “God Made My Face” is another historic exhibition, in the scope of its contents, the approach to its subject, and the inclusion of new commissions alongside existing rarities.

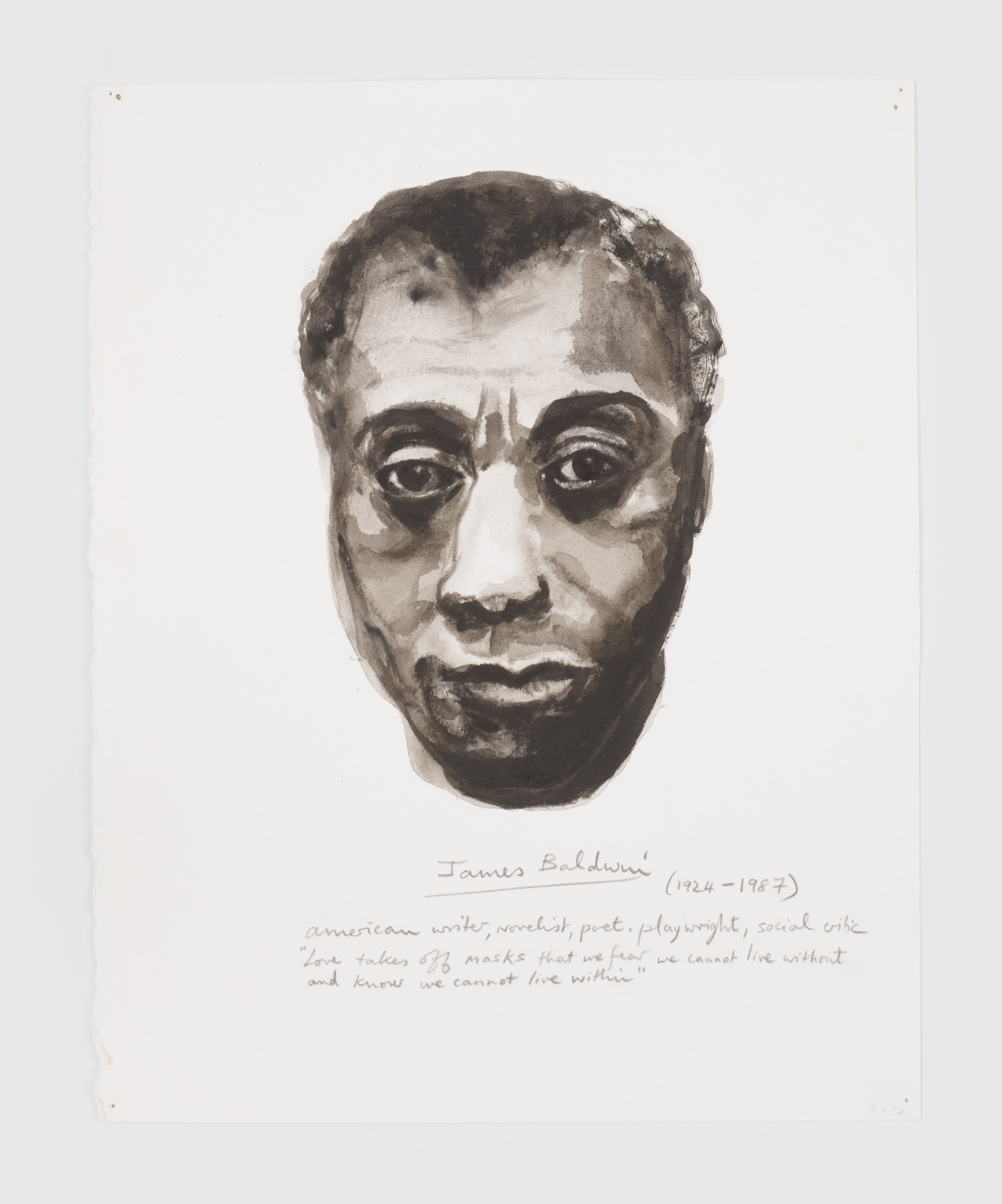

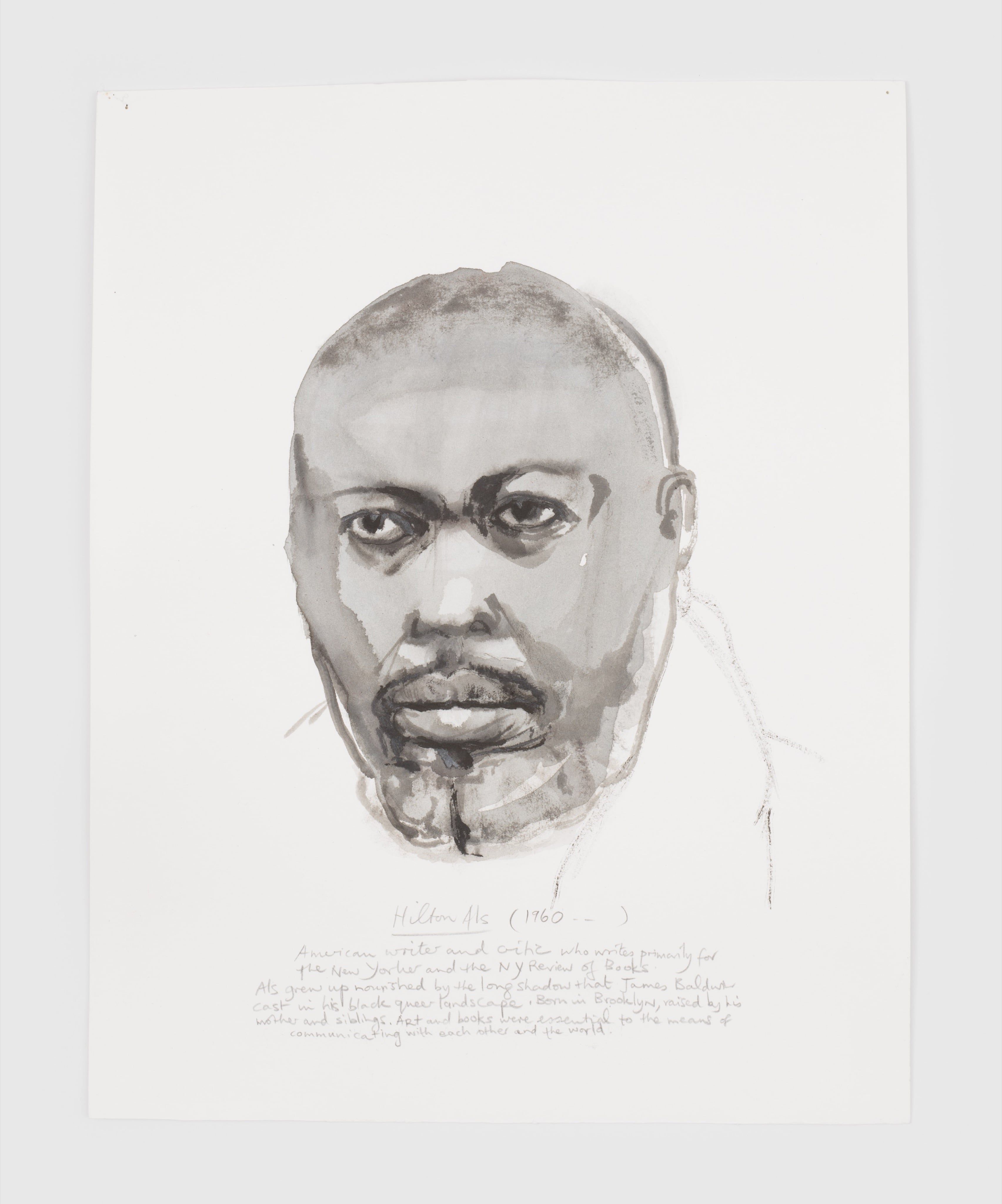

Presented, for example, is a series of new works by Marlene Dumas (also featured in 032c Winter 2018/2019), created at Als’ invitation and depicting Baldwin and his inner circle. Als spoke to me in the days following the opening of “God Made My Face” about his personal relationship to Baldwin’s work, its global reception, and its Hollywood adaptation. We can never go back to the time and places Baldwin inhabited, we concluded, but the humanity of his legacy resounds clear and influential in our trans-Atlantic present.

How did you come to curate a how about James Baldwin, and how did you come to the approach you take in “God Made My Face”? Obviously, Baldwin is heavily present in the zeitgeist.

Well the show started with the idea that I was irritated with a lot of the conversations around Baldwin. Most of them really had to do with the fact that he was erased as a body. One of the things that was offending to me was that a person who had been around veiled or unveiled conversations about queerness, and black queerness in particular, had been really relegated to a kind of bloodless prophet. So when David Zwirner asked me what I wanted to do after Alice Neel, Baldwin really came to the fore. The visual work in the first section of the show is kind of biographical, and the second piece is metaphorical, meaning it gives the space over to the kind of art Baldwin might have made had he been able to or been challenged to. So those were the parameters that I had in mind. And I really like working from the prospect of – I sort of like being marginalized. Because it means that you’re fighting more creatively to be seen. Baldwin to me wasn’t someone who would have been particularly comfortable being canonized. Given his relationship to the living, in essence, and how much he invested into living. No one knew how he got the novels done, because he also lived a very full life. And no one knew how he got the plays done because he was a civil rights activist. There’s an interview where he says something like, “I never want to be in an ivory tower cultivating my talent when all of this is going on.” He was split between the interior experience of the artist and the exterior life that a public spokesman or performer lives.

“God Made My Face” – that’s not a Baldwin quote.

No it’s not – it’s a little children’s hymn. “God made my face, god made my hands . . . god made me.”

It’s interesting to me that the title situates it in this religious or spiritual framework – which is what Baldwin came out of, having been something of a preacher in his youth.

I really did want to pay homage to the complicated beauty of his faith. I think that he was one of the more faithful authors that I’ve ever encountered, precisely because of how he managed to exist outside of an institution. I think he really only resented the church as an institution – I don’t think he resented it as a mode of belief. I think that he had enormous faith in his friends and I think he had enormous capability in the world. And that wasn’t just a will. It was really the faith he had gotten from his mother, first of all, or from Orilla Miller, who was a teacher of his. It’s sort of like if you have these various people who really love you and care about you … you might not want to be in the church, but you will have a kind of belief that faith is a possibility.

In The Fire Next Time he has a line that makes me laugh: “The church was very exciting.” And he knew how it worked – that’s the mark of a shaman, not just a preacher. He was able to talk about how he was really wasn’t the kind of person who should be in the church, because he was never part of the community. That’s another thing I wanted to stress, is him being a maverick. And how lonely that was, and how beautiful for us.

You know, when I was in Berlin last summer it felt more expensive and more alienating than I remembered it from the mid-2000s, when I was at the American Academy. Is it weird for you being back?

It’s interesting that you asked. When I moved here in my early 20s, I feel like I just slid right in. I left for a decade and came back in 2018, and I did find something more alienating here. Maybe it was cheaper, and maybe I was naïve to Berlin’s cultural specificities a decade ago, when the city felt like a playground and a space that hadn’t really crystallized as anything yet. Speaking to others about this though, there is a feeling that as Berlin has grown and become more cosmopolitan it’s also become more hostile to difference.

There’s an expression in German that means something like, “staring without responsibility.” And I felt on the subway that people would just come and sit in front of me to stare at me. There’s this Jane Kramer piece about neo-nazis in Berlin from 1993, which feels just like Berlin now. If you’re a person of color. I couldn’t wait to get the fuck out of there.

You mentioned that part of the exhibition is biographical, but there is also reference in the exhibition literature to your autobiography, to Baldwin being formative for you.

Well we have similar problems! (Laughs.) So that’s going to come out in a sense too. When Baldwin for instance moved to Paris, it was right after the war, and he didn’t have what Maya Angelou called “particular guilt” about black Americans… so he was able to live more freely. But that temperature doesn’t really exist in places like Paris anymore. I feel most comfortable now in London. I go as a relatively privileged guest, as an artist. But more certainly they can’t place me, because of the accent, and that I find incredibly freeing.

Paris was the 19th century seat of the avant-garde, New York was the 20th century cultural center. We’re in the 21st century. Where would Baldwin go now?

I think it’s less a question of place right now than of possibility. I mean obviously you’re going to work in a place where you won’t blow it in terms of our work. It’s sort of like we have to do more diligent homework, to take care of ourselves. We’re here thinking about our longevity. So how can we make that happen? Artists are always in transit, how do we make a home for ourselves? I think that’s a big question. I think that was one of Baldwin’s big questions. When Baldwin went to Paris in his early life, he could live in hotels, he could live that way of life really well there. I think that was one of Baldwin’s big questions. “You can’t go home again.” So I think he had a lot on his shoulders, vis à vis his isolation. I think he wanted to be away, to be with his own voice. Because it can be such a drag listening to everything else – imagine trying to be a gay black artist in New York in the 1940s. Imagine! It’s amazing when you think about how much we’re given, and how little he was given. And how much he made out of that. So some of what the show is about is paying homage to that incredible will. A great will went into his making – and into making himself. … You can’t repeat a life like that, you can’t really have another one of him because he was inseparable from his time.

You made a comment in another interview about how Baldwin’s later fiction suffered because his polemics took over and there was no longer any room for his creative voice.

I just think that it’s difficult to leave space for everything when you become a performer, in some ways. And Baldwin became a performer. His performance relied on a great materiality, as you’re expressing something that’s outward as opposed to your internal life as an artist. Those are two things that were really at war in his psyche and in his being. And I think that unfortunately, the art – the novels, I should say – lost to the public person. And the essayist struggled to have his own voice.

The only work of Baldwin’s to be adapted for narrative cinema is one of these later novels, If Beale Street Could Talk. The film is directed by Moonlight‘s Barry Jenkins, who you’ve written about before. I’m dying to know your thoughts.

If Beale Street Could Talk was really two books in one. Baldwin is always talking about witnesses and needing a witness and wanting a witness, and I think he wasn’t able to find an editor-as-witness to sit down and say, ok we have two books here. Movies are often made from weak books, but with the timing of this version, we’re treating it as hallowed material.

Beale Street deals with urgent topics such as race and the justice system, but avoids the queer narrative, the domestic intimacy and tactility of some of his other fictional works. So why adapt this piece instead of something like Giovanni’s Room? Is it because its message is seen as more digestible?

You know, the show is in part a response to the things I felt were really excised from Baldwin’s life and work. And the queer narrative is one big example, for sure. The estate is complicated. The libraries have so much incredible material, and you can’t publish it. But you can display it. So in the show there are letters he wrote to his teacher and so on that are just extraordinary. I think his great work is really in his letters. He was an incredible epistolary author, I just wish there were more opportunities for people to read the letters.

Tell me about the Marlene Dumas contribution – she has painted Baldwin before, but the works on view are entirely new?

She’s done them for us, isn’t that amazing? It was the best collaboration with a visual artist ever. Because I would just tell her stories about people that he knew and that I had met through my mentor, Owen Dodson, and she would ask, not much, just a little question. Like, “when were they born?” I would send her photographs of the person and she really took it to a new level of synthesis, taking that information and really interpreting it so beautifully and gently. She really gave herself to the project, and to me, and to the history of those guys. I just love her for it.

Can you comment on your personal process or relationship to curating these materials, particularly as a writer yourself?

When I was starting out at places like the Village Voice and Vibe, my job was always visual. I worked in the art department at the Voice and I wasn’t really hired as a writer until Tina Brown hired me at The New Yorker. So I always worked in both spheres of experience – text and image have always been equal in my mind. The various parts of my brain come together on the page and they come together in the gallery. Differently – because you’re working spatially – but both things require that you work out of your interior. The thing that’s great about a gallery, and about working with someone like David Zwirner, is that you’re being supported, and you begin to understand space in a different way. It’s like having a big beautiful playground all to yourself for other people to come into.

Baldwin famously left a play, The Welcome Table, unfinished when he died. What is the work around Baldwin that you feel still has to be done, or that you hope this show will do or incite?

What I’m hoping is that there’s a much more expansive reading of his life and work after this. That this contribution to his complication becomes part of a new conversation about him. That’s what I’m hoping for.

Credits

- Text: Victoria Camblin