The Spiral Walker: JULIE MEHRETU

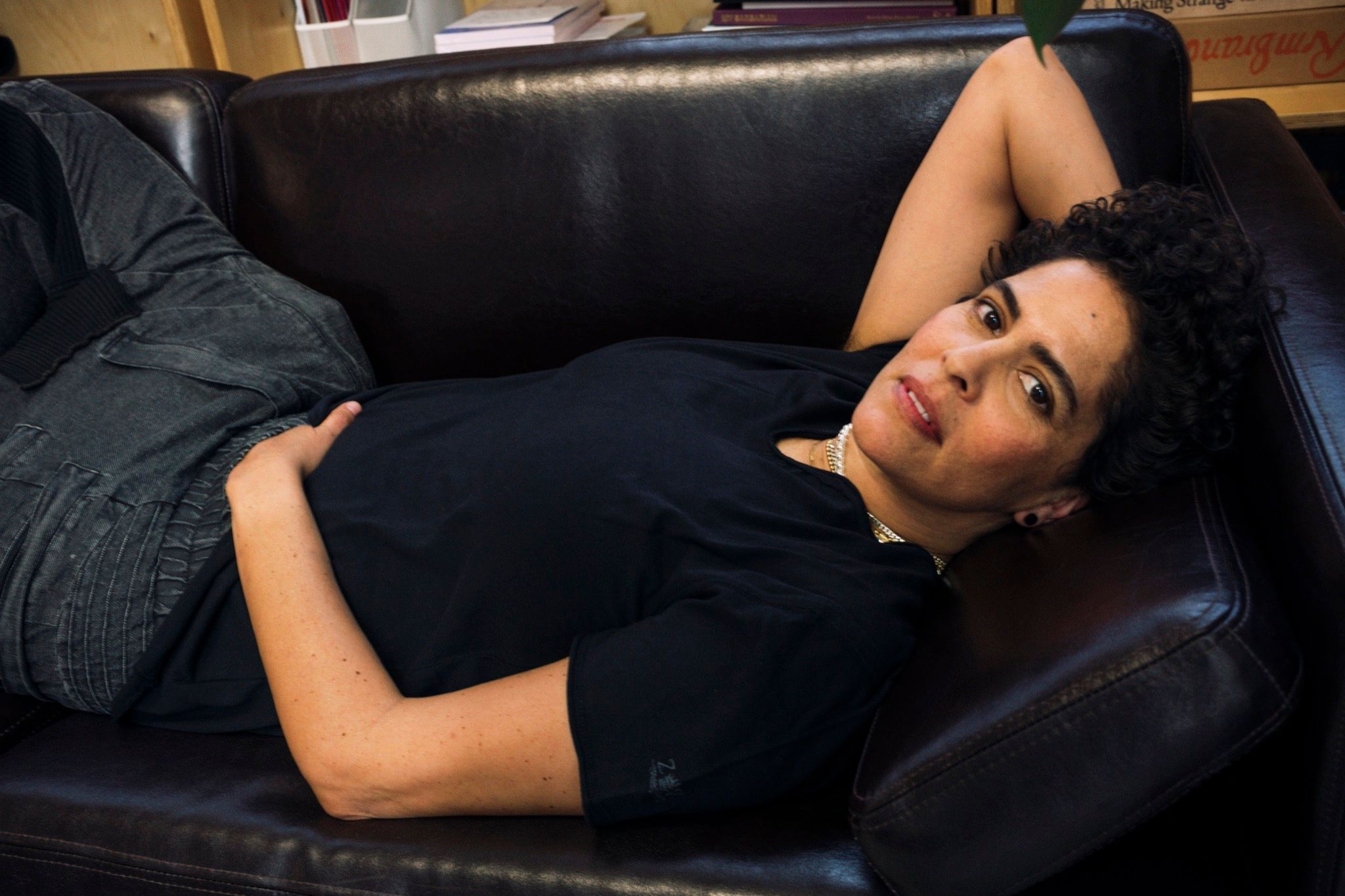

|DURGA CHEW-BOSE

“The BMW Art Car is only completed once the race is over.” To celebrate the participation of Ethiopian-American artist Julie Mehretu’s BMW Art Car in this weekend’s 24 Hours at Le Mans, we’re republishing Durga Chew-Bose’s feature on the artist from 032c Issue #41.

June 17, 2024 — Described by the artist as a “performative painting,” the BMW M Hybrid V8 race car was transformed into an object marked by ideas of glitch and acceleration. For an artist whose work the late curator Okwui Enwezor once described as “dynamism in form,” Mehretu’s longstanding interest in the blurring of contemporary experience finds its visual corollary in the imperceptibly fast movement of a race car. The 20th BMW Art Car’s participation in Le Mans marks nearly fifty years of the BMW Art Car Program, an initiative begun in 1975 with a collaboration with Alexander Calder and which has been continued by the likes of Andy Warhol, Robert Rauschenberg, Jenny Holzer, and John Baldessari. The car unfortunately crashed into the tire wall just a couple of hours into the race. However, after lengthy repairs, the car ultimately returned to the race, crossing the finish line and actualizing Mehretu’s vision of the work’s completion.

JULIE MEHRETU’S CANVASES ARE SLEEPLESS

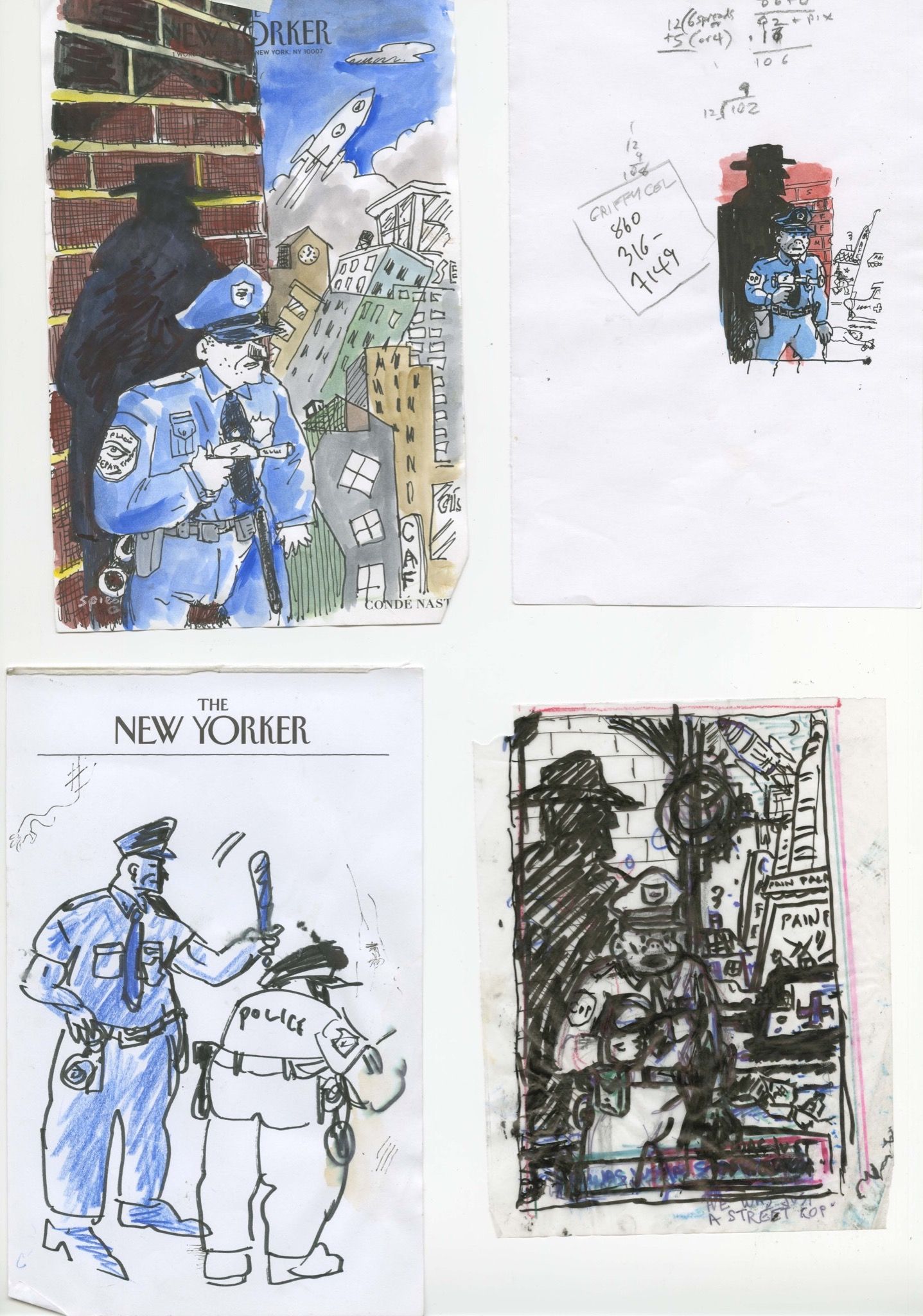

JULIE MEHRETU spends most of our conversation drawing on a piece of paper I cannot see. The artist tells me she draws whenever she is talking, and I wonder if drawing, for her, makes easy the act of listening, because Mehretu never seems unfocused. Her attention is fixed, receptive, joyful. Drawing is her way in, the opposite of distraction. Drawing is her version of paying attention. Even while she is finding the words, the drawing is going.

Mehretu is sitting at what I imagine to be her desk. Behind her, a white stepladder stands open for use. Some art hangs on the wall. Mehretu – who has lived in New York since 1999, more or less – describes the space as a makeshift home and studio, bedroom, and packing center. From what I can see, it’s sparse but lived in, and not in a cluttered way. There are no piles or other comforting signs of wear; perhaps they are out of frame. It’s possible that my interpretation has nothing to do with the space and everything to do with the acclaimed 52-year-old artist’s hospitable tone. She speaks with incredible warmth and answers questions considerately, never pausing long to deliberate. Her insights come quick yet remain searching, with occasional corrections mid-course. She is never entirely satisfied. “I’ll have to give that more thought,” she says at one point, smiling. “This is just intuitively what I’m coming to.” Later: “It just occurred to me. I could be wrong.” And so on.

I come to understand intuition as a feeling Mehretu deeply vouches for – a feeling she terms her “sixth sense” and likens to a sensual sense of making. “There’s a lot more work being done now to understand, cellularly, how much is inherited, and how much knowledge is embedded in us, and how much that could also be directed to a thing that can play with intuition, and form intuition, and form what we think of as these chance possibilities, or these kinds of signs or omens, or this sense of knowing something without knowing it. How much unknowing is a part of knowing?”

Mehretu, who rose to art world prominence in the early 2000s, is a 2005 recipient of the MacArthur Fellowship. Her first comprehensive mid-career survey, organized by LACMA and the Whitney Museum of American Art, just wrapped up its final stop at the Walker Art Center. Despite all the press, Mehretu is eager for real critical conversation. Like most artists, she is uninterested in talking about what her work means, compelled instead to talk about what her work might draw attention to. She would rather focus on how culture is made now, but always in relation to how it was made then. Documenting the urgent circumstances of this moment in time – reworking photographs of such uprisings as the Arab Spring and Black Lives Matter, or of the California wildfires and the burning of Rohingya homes in Myanmar – is essential to her sense of invention and, literally, to her work and her underpaintings.

Recently, Mehretu partnered with artists Rashid Johnson, Adam Pendleton, and Ellen Gallagher to buy and preserve Nina Simone’s childhood home in Tryon, North Carolina. I ask Mehretu about her relationship to legacy. “It’s super complicated,” she says. “It’s complicated for everyone. But it’s also super important in a moment where a lot of that is being denied in history. In the US, we’re really struggling with that right now. You have laws being created to deny the teaching of race in schools. That’s the opposite of truth and reconciliation; that’s the other direction. So, in this world, I want to say that this conversation is about understanding when we talk about legacy, what does that mean? I’m much more interested in larger cultural implications, and one of the reasons I love and am so interested in art of all forms is because it becomes this way of understanding being human.”

“Always curious, always had too much energy, couldn’t sit still – always wanting to move, constantly engaging with the larger world,” Mehretu tells me when I ask her how she was described as a child. “I probably had some form of ADD when I was a kid. I hate describing people in that way, but I was very active in that sense. I wasn’t a typical student, but I always made work. I loved to draw. I loved making stuff. I was a really social kid. I still am. I was able to get a lot out of being social.” Born in 1970 in Addis Ababa to an Ethiopian father and an American mother, Mehretu was the eldest child. In 1977, her family fled Ethiopia and emigrated to East Lansing, Michigan, to escape the political violence brought on by the country’s Derg military junta. In 1997, Mehretu received an MFA in painting and printmaking from the Rhode Island School of Design.

Mehretu’s large-scale canvases – rock climbing has helped with her fear of heights, she tells me – move with remarkable celerity. It’s as if the artist paints into the canvas, quarrying speed, attendant to the accelerative powers of confusion and bewilderment. The latter state, described by author and poet Fanny Howe as “an enchantment that follows a complete collapse of reference and reconcilability,” seems kin to Mehretu’s ever-evolving project. Both artists circuit and suspend. For Howe, the experience of her interior, before it exists on the page, is a dream, “one continually returning pause on a gyre.” She calls herself a “spiral-walker” with no plain path, just strange returns and recognitions. “[Bewilderment] cracks open the dialectic and sees myriads all at once,” writes Howe. “I have learned about this state of mind from the characters in my fiction – women and children, and even the occasional man, who rushed backwards and forwards within an irreconcilable set of imperatives.” This vibrational journeying, as Howe notes, rejects being found or downright explained. Mehretu shares similar thinking, reflecting on some of her recent work as “this completely ungraspable kind of being ... eluding understanding.” There is no ultimate or eventual. Nothing caps or is crystalline. Why risk specifying the thing only to limit it?

Mehretu wonders out loud if she might be a storyteller. I believe she is. “I am interested in the kind of illegibility of the paintings. What can come up in that illegibility, or the space of just having to viscerally experience them. That was also a reason I was so interested in going so large with the scale: to get away from narrating these smaller works that I was making before. What happens when that gets blown up to a different scale? You still have that intimate scale; that becomes a very physical thing. You can’t read that unless you’re very close to it, and when you’re close to it, you can’t experience the whole thing.

“You never want to make sense of someone’s imagination, but make sense of someone’s desire, impulse, or where they are coming from. Creating an imagination is super important. That’s the space I am trying to protect and cultivate the most.” Her Chelsea studio, which Mehretu has had for going on 12 years, shelters that “imaginatory, liberatory space.” It’s big and open, with 12-foot ceilings, windows that overlook the Hudson River, a kitchen, and lots of plants. “It’s flooded with light. I work with a group of people – there’s about two full-time people and four part-time people, and they’re all artists who work on their own work. We all cook together for lunch every day. It’s very intimate.”

In the same text of Howe’s on bewilderment, the author continues: “There is a Muslim prayer that says, ‘Lord, increase my bewilderment,’ and this prayer is also mine and the strange Whoever who goes under the name of ‘I’ in my poems – and under multiple names in my fiction – where error, errancy and bewilderment are the main forces that signal a story. A signal does not necessarily mean that you want to be located or described. It can mean that you want to be known as Unlocatable and Hidden.”

“How much unknowing is a part of knowing?”

Mehretu, who has described her canvases as “story maps of no location,” refuses stillness. Her art is concerned with destabilizing forces. Shifts! The big tectonic kind, but also ones that occur incrementally, in communities that are overlooked, forgotten, erased, colonized. Themes explored in her oeuvre are wide-ranging, propulsive, and deeply researched, epic yet everyday: migration, deracination, war, nationalism, global capitalism, the individual vs. the group or the tribe, topography and geopolitical studies, cultural histories. There is a feeling for extreme simultaneousness; what interconnects must clash and then diverge. I am reminded of a quote from Marguerite Duras’ The Lover (1984), where early in the novella, the unnamed narrator says, “Sometimes I realize that if writing isn’t, all things, all contraries confounded, a quest for vanity and void, it’s nothing.”

Contraries confounded. In Merhetu’s case, one gets the impression that hers is a turbulent deep space with layers upon layers of interred forms, both freed and wondrously encumbered by contradiction. Paintings, prints, and drawings that are alive with potential – a potential that is peculiar to doubt, not certitude. Everything is metabolized. Nothing is metabolized. What rises from collapse is neither the beginning nor the end, but the continued spectacle of in-betweenness. There is no landscape without an event, no event without the land on which it takes place – land that can- not be estranged from its political history, its colonial history.

In Stadia II (2004), which is one third of a triptych, Mehretu’s demagnetized forms are stirred up, ecliptic and phenomenal, set in what appears to be a speculative opening ceremony. These forms are, to borrow from Howe, Unlocatable – despite Mehretu’s source material, which includes city maps and architectural plans. The monumental scene is familiar, but only to a fleeting point. Is that an American flag or a bank logo? Or a bank logo made to look like an American flag? What is it about curved lines and strange, colorful geometry that brings to mind gymnastics uniforms? Can you hear the firm landing? The soundlessness of the pommel horse? Does anyone else see pool lane dividers? Why is the energy of this canvas somehow competitive, Olympic, Extreme? Extreme like the weather, a strong gale at its center. Its tiered, cyclonic build resembles a tempest of allegiances. Are those championship banners in a college gym or retired jerseys hanging from the rafters? Symbols of legacy in nylon, mesh, vinyl.

Vibrant and responsive, the collective shapes are fundamental. Like one’s first experience of a circle or a rectangle, attributed, it’s possible, to an advertisement or cereal box; the way colors in corporate logos are incipient, committed to our minds from a young age, like it or not. Red and yellow: Shell, McDonald’s. Fuchsia: donuts, tacos, T-Mobile. A blue square: The Gap. A blue oval: Samsung, Ford. Two circles: MasterCard. Four circles: Audi. Diamonds: Mitsubishi. Green: coffee, lawn mowers, chain hotels, Tic Tac. Stadia II exemplifies Mehretu’s use of propulsive markings and inclement scrawl. Her lines are alight or unsinkable, her shapes like sails – the dream kind of sail you might imagine not on ships that travel the sea but on ships you encounter in the sky.

I pause at what looks like a string of small, triangular flags. My memory is switched on, and what materializes is very specific. A decade ago, I traveled home to Montreal for the funeral of my uncle Charles. My father picked me up at the airport – after an early morning flight from LaGuardia – and on our drive home, we stopped at a red light. Until this moment, we had both been very silent, lost in thought. I had been thinking about my uncle’s wife – my mother’s sister. I remember feeling hungry. At the red light, to our left, was the huge, 150,000-square-foot main printing facility of the (since shuttered) Montreal Gazette, built in 2002. Shiny and characterless, it had always looked new in a way that seemed simulated and anonymous, like the digital rendering of a building. Even the landscaping seemed aggressively plain, aggressively manicured. As we both stared at the building, a mischievous smile suddenly grew on my father’s face. I assumed he was about to share a memory of my uncle Charles, but that’s not how life works. That’s not how mourning works. Instead, he pointed to a small second-hand car dealership bordering the printing facility’s land like a campsite. It was nothing. The size of a few driveways, if that. The cars were old, and from what I could tell, real lemons. But what was so remarkable about the dealership, and what ultimately made my father smile, was the owner’s commitment to this small piece of land. It was his land, not the newspaper’s, though I can only imagine they had offered to buy it from him, plenty of times. And he wanted it known! This land belonged to him! So, what had he done to claim it? Hanging above those busted cars were hundreds upon hundreds of small triangular flags, flapping in the wind. Some of the flags were shiny, but most of them looked ripped, misshapen, faded, weather-beaten. It was an extremely ugly, dazzling sight. It was satisfaction and pride, in the way flags are proud. This is the type of pleasure and mischief that entertains my father. These are the types of stories he has raised us on. I hadn’t thought about that car dealership in years, and now, with my father sick again, the memory is particularly important. That car salesman’s stalwart spectacle of flags is a fantastic state of mind.

Early in our Zoom, I ask Mehretu if there are any touchstones she returns to – any art, of any medium, that re-establishes her intuition, nourishing an idea beyond the materiality of an idea. I’m curious about the art, by other artists, that Mehretu reopens when she wants to access her insides. She acknowledges that it changes over time, but shares a few examples, including the famous cycle of paintings by Caravaggio dedicated to St. Matthew in the Church of St. Louis of the French in Rome. “I have seen it almost every year for 30 years,” she says. “They are a unique experience because they are made for that space and have not been moved from that space. There is this intentional way that the light works in between the three paintings and the different narrative structure that is trying to be created in each of those paintings.” Mehretu also mentions David Hammons, particularly a body print of his that lives in her home. “It’s a piece that beckons me upstairs. Every morning before I leave, it captures me. There is something in it that constantly is transformative, a chemical that shifts and mutates as you experience it. At times you see handprints, puzzle prints, or a third eye, or the third eye is the mouth.”

Finally, Mehretu cites the music: Ornette Coleman, John Coltrane and Alice Coltrane, Betty Davis. It’s unsurprising that music plays a determining factor in her work. Contrapuntal and euphonic, Mehretu’s paintings are open to double meanings, alive with the sonic glory of spontaneity, of refusing the categorical and floating instead toward the ecstatic. Her canvases are sleepless. They are home to wreckage, entropy – echoes of blasts and booms – and the awesome, even repercussive nature of accumulation, inheritance, and diasporic histories. Her canvases also receive tentative forms like ghosts, aftershocks, and aberrations, and the transparent splendor of gray. There is a sense – a promise, actually – that you might miss something when you spend time with Mehretu’s art. But isn’t that by design? To get close enough so that you can’t experience the whole thing; to step back and lose out on the canvases’ intimacy. I think back to what Mehretu said early in our conversation: how much unknowing is a part of knowing?

Credits

- Text: DURGA CHEW-BOSE

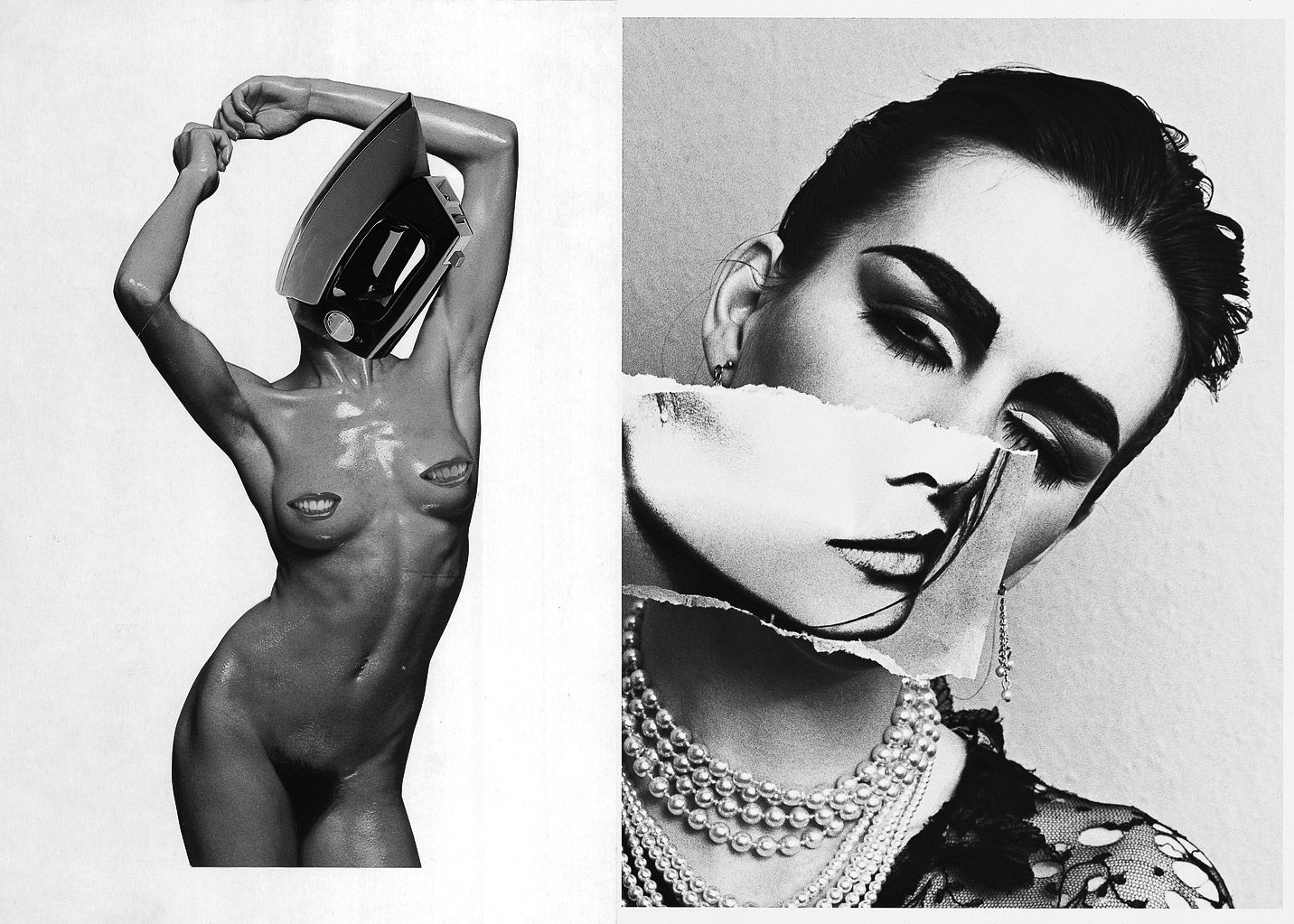

- Photography: NAN GOLDIN

- Fashion: KEITA LOVELACE

Related Content

Art Under Construction

SPRÜTH MAGERS: The Art Gallery and the World

The Real Thing: Exhibiting the Art of the Bootleg

The Principles of Trap Feminism

Coded Images: CAITLIN CHERRY on Bodies, Access, and the Interface

Fuck Morrissey, Here’s Linder

ALEXANDRA BIRCKEN: Bodyrevolt

Despair and Dystopia Next Door: ART SPIEGELMAN in conversation with HANS ULRICH OBRIST