Art Under Construction

|NIKLAS MAAK

Collector CHRISTIAN BOROS is moving his art into a renovated Nazi bunker. A visit.

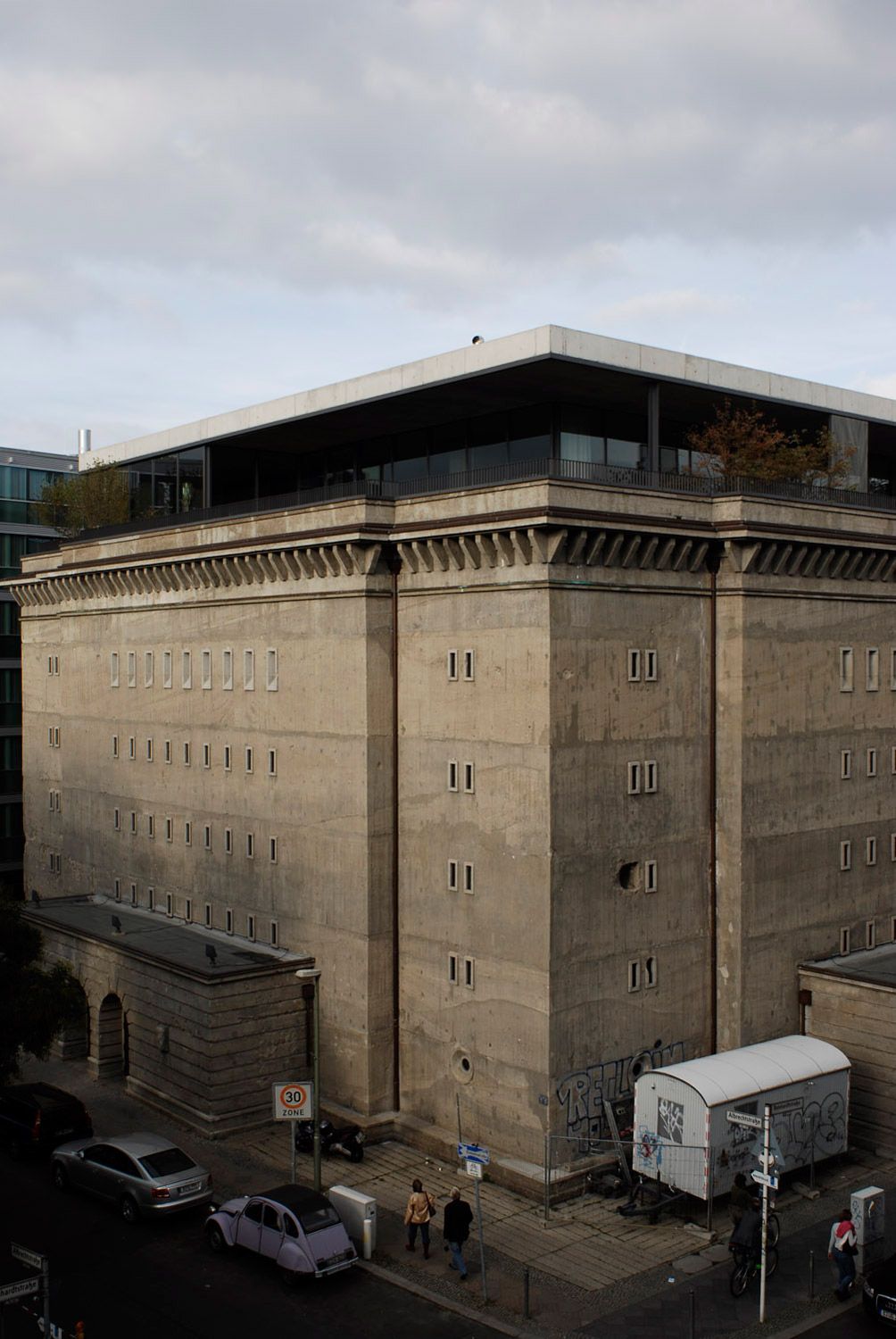

Perhaps Karl Bonatz didn’t know quite how desperate the situation was. Or perhaps he knew, and his architecture was part of the propaganda that was intended to give people the feeling that his cement box was not a bunker first built to protect from air raids, but rather a Neo-Roman bastion, in which people had once defended themselves from charging knights.

“In 1990 the techno and fetish scene entered the bunker, and if one were to believe those that were there, it seemed like a strange return to history that grim-looking people in leather coats carrying riding whips were suddenly making a reappearance there.”

In any case, it is an absurd architecture, designed in 1941 by Berlin director of urban construction Bonatz, who obviously believed that he still had enough time at that point to decorate the air raid shelters with rustic entranceways and Germanic risalits. The bunker on Reinhardtstraße was completed for the Reichsbahn in 1942 and designed to offer protection to some 3,000 travelers from the Bahnhof Friedrichstraße. And up until four years ago, when Christian Boros purchased it in order to adapt it to house his art collection, things took place there that its original builders wouldn’t have been capable of imagining, even in their worst nightmares.

After WWII, the Red Army converted the bunker into a prison. In the mid-’50s the state-owned enterprises began storing bananas and exotic fruits for the privileged in its cool rooms. In 1990 the techno and fetish scene entered the bunker, and if one were to believe those that were there, it seemed like a strange return to history that grim-looking people in leather coats carrying riding whips were suddenly making a reappearance there.

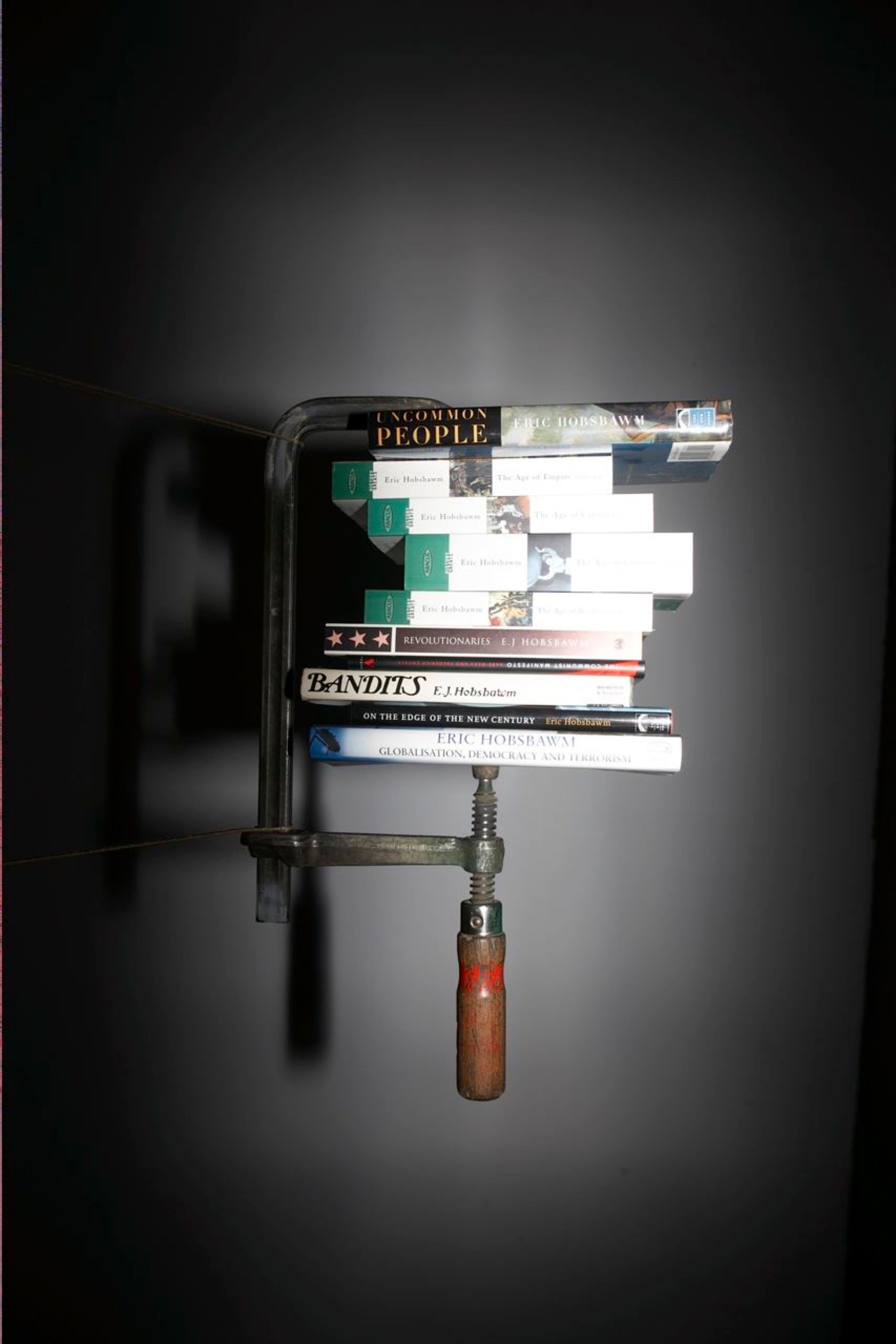

“The ventilation was abysmal, so people’s sweat would condensate on the walls,” says Boros. By midnight people were dancing in puddles throughout the cement dungeons. In 1995, the “Sexperimenta” festival took place in the bunker, following which the cultural and fetish scenes took turns using the space so frequently that one no longer knew whether the leather straps hanging from the ceiling were art or something else. One had to look closely in order to determine if the people dressed in black at the door were fashionably attired for the art scene or the fetish crowd. In 1996 the “Overture of Lust” took place there, but so did the art exhibition “Files,” in which Olafur Eliasson and Ugo Rondinone participated. One of Rondinone’s works – a black and white painting – remained forgotten on the wall; Boros unearthed it ten years later.

Boros, born in Poland in 1964, came to Germany at age nine, studied the Baroque with Bazon Brock and wrote his thesis about the stage set designer Klaus Hugo Adam, who fled the Nazis in 1934, becoming famous under the name Ken Adam as the set designer for the James Bond films. While still a student, Boros founded an agency in Wuppertal, invented the logo and ad campaign for the music station Viva, worked for Coca-Cola and the Green Party, and bought a lot of art on the side. Perhaps it was his love for Ken Adam that gave him the idea to move into the bunker.

In 2003 the Berlin architect Jens Casper was tasked with the redesign, and the interesting thing about it is that the architect did nothing but cut away walls and ceilings – although perhaps “cutting” is the wrong word when it concerns walls that are meters thick and the ceilings are made of three-meter-strong reinforced concrete.

In any case, Casper had the building hollowed out like a gorge (all the concrete pieces, amputated with diamond saws, had to be carried out by hand); he connected the 161 claustrophobic rooms of the bunker to form atria, created angles of visibility, made space for large sculptures and transformed the narrow cells into a generous labyrinth of rooms that run into each other, overlap and break open like an early Le Corbusier villa. Casper literally deconstructed the bunker: he took apart, removed, made it more open and playful, invented an artful, mobile system of creating rooms by taking away – and he milled 150 cubic meters of steel-reinforced concrete out of the three-meter-thick ceiling. Through the resulting hole, which is reminiscent of an opening in a rock cavern, one can reach a bungalow situated on the flat roof, which looks like a mix between a minimized National Gallery and a Neutra-villa. Below this are 2,500 square meters for the collection, which will be installed shortly and should be available for viewing by appointment within the next year.

Not on view is the bungalow on the roof, however, which is a luxurious, pioneering version of something that should finally catch on – namely, the construction of apartments on the countless flat roofs of the city that offer everything that single family home builders in the countryside are looking for: sun, peace and quiet, a small garden.

The house on the roof of the bunker and the excavated exhibition landscape are a special form of what is called superimposition in architectural theory – not merely a spatial, but also an ideological conversion, a triumph of American modernism over the theatrical thundering of Nazi architecture – of the bungalow and the free layout over the bunker. The apartment itself is borne from an obsessive perfectionism worthy of Ken Adam – an orgy of the finest materials with almost four-meter-high exposed concrete walls, a floor made of coquina and fixtures and fittings made of smoked oak. Just how detail-obsessed the architect and his client were in staging the perfect living environment becomes evident when one touches the door seals: they’re not made of rubber, but of calfskin. Behind the glass façade, pears still grow over the terrace, as though the bunker were still a ruin, and the water of a small pool casts reflections onto the cement ceiling.

How one can suddenly shift, in one building, between the present and the depths of history is also evident in the gallery house on the Kupfergraben, not far from Boros’, that Heiner and Celine Bastian had built by David Chipperfield, and that above all stands for an alternative to prevalent Berlin architecture. While one nearby reconstructed 1873 commander’s headquarters imitates a historical décor with new materials, which makes the building look a bit like a crème torte made of hard plastic, Chipperfield follows a different path. He designs a strictly modern vision, but uses historical materials: the bricks, for instance, are from torn-down Dutch and Belgian factories. Just like Casper’s bunker construction, Chipperfield translates the rooms’ high ceilings and the material opulence of classical architecture into modern forms – his house has the most beautiful of Berlin’s new stone façades; it looks contemporary and at the same time historical, as though someone had hammered windows into the aurelian wall. Thus, thanks to new works of architecture that hollow out the old, overbuild, re-wall, and activate, it has come to pass that in Berlin, a city obsessed with history, an amusing confusion takes place: the new suddenly has much more historical aura than the old that’s been rebuilt.

Despite all this – isn’t it just creepy to live in a Nazi bunker? To see gas detectors and other survival apparatuses from 1942, every time you step out to go to the bakery?

“It feels comfortable and secure here,” says Boros, as we leave the villa on the roof and head for the elevator, press zero and descend into the concrete monster. At the bottom there’s a sudden lurch and the elevator gets stuck in the middle of the bunker. This was one of those moments when certain questions arise: how those folks in movies get out of stuck elevators (can‘t remember); whether or not your cell phone signal is able to penetrate cement walls that don’t even let bombs through (it isn’t); whether an elevator repairman – should he even hear us – would be able to open the 100-kg antiaircraft door that’s bolted from the inside. After some time we pressed the alarm button and somewhere in the bunker a siren hooted, but no one responded to the emergency call. It got late, it was very quiet and a bit cramped, and the siren trailed off unheard like everything that happens between two meters of massive cement. Luckily, the door let itself be pried open with our hands, and we climbed out into the darkness of the basement, where the ventilators of the Third Reich shimmered strangely.

Credits

- Text: NIKLAS MAAK

- Photography: OLIVER HELBIG