The Icelandic Condition

For decades, the Icelandic writer SJÓN has dazzled international readers with his brisk yet enchanting novels that fuse the otherworldly with the historical, the mundane with the extraordinary, and the surreal with the real.

Writer AS Byatt has called him “a Magus of the North,” and Junot Díaz has suggested that “Sjón is the trickster that makes the world.”

The recipient of several awards, including the prestigious Nordic Council’s Literature Prize for Blue Fox in 2005, Sjón (whose birthname is Sigurjón Birgir Sigurðsson) began his writing career at the age of 16 when he published his first book of poetry in 1978. During his late adolescence and early adulthood, he was also a founding member of the neo-Surrealist group of artists called Medúsa, who published poetry, held exhibitions, and created bands under the flag of Surrealism’s revolutionary potential to navigate new ways between the conflicting desire principle and reality principle—something which will mark much of his writing.

While active in Medúsa, Sjón befriended Björk, for whom he would write lyrics on several albums. Having once told The Guardian, that he’s “one of the few people who’ve had Björk as a backing singer” in one of his bands and having performed with her in The Sugarcubes and their duo Rocka Rocka Drum, Sjón would then collaborate with the Icelandic avantgarde popstar on the lyrics for “I’ve Seen It All,” featured in Lars von Trier’s Dancer in the Dark (2000), which she also starred in. This would be Sjón’s first foray into film, and he would later co-write the screenplays for Vladimir Jóhannsson’s Lamb (2021) and Robert Eggers’ The Northman (2022).

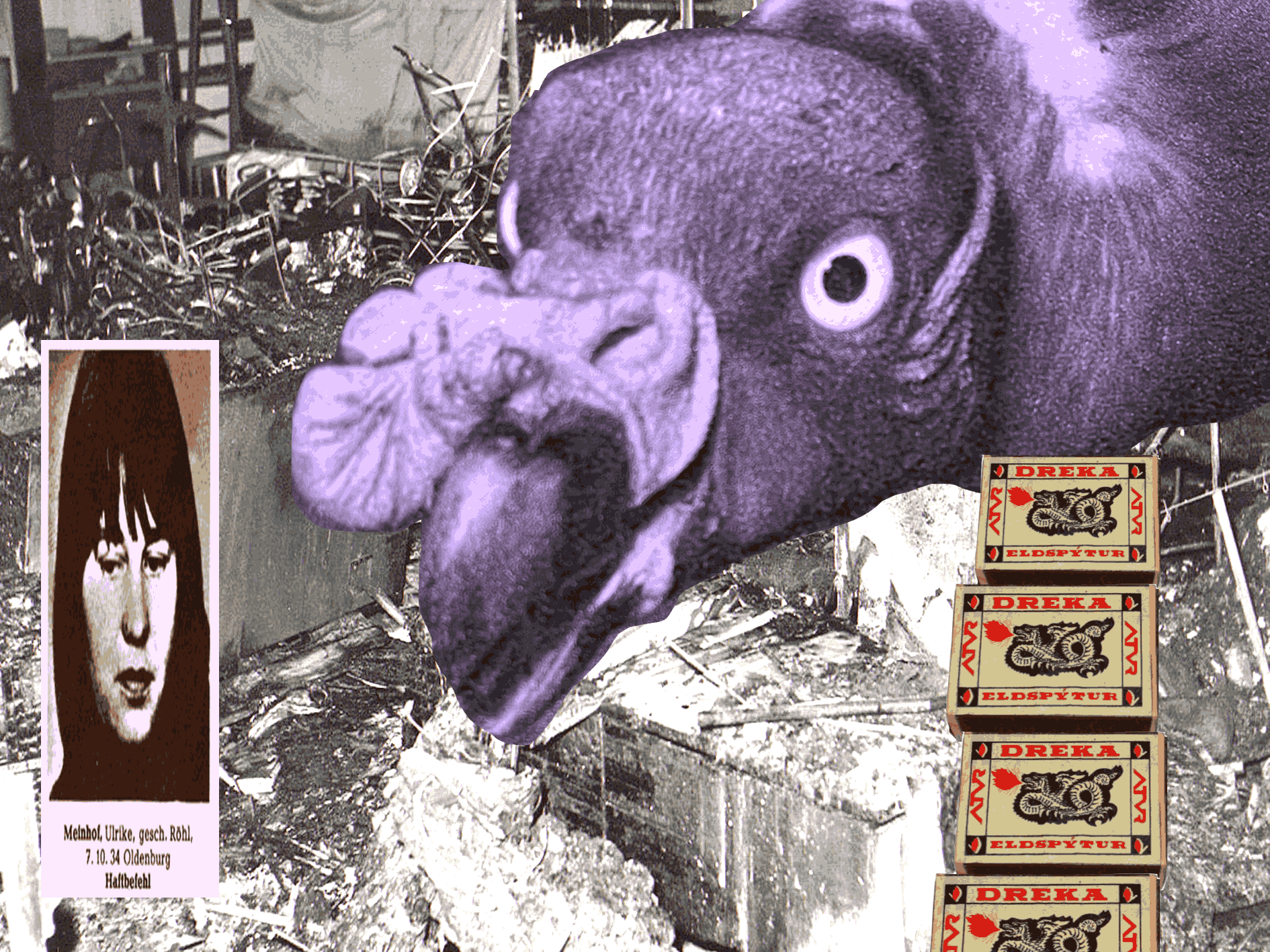

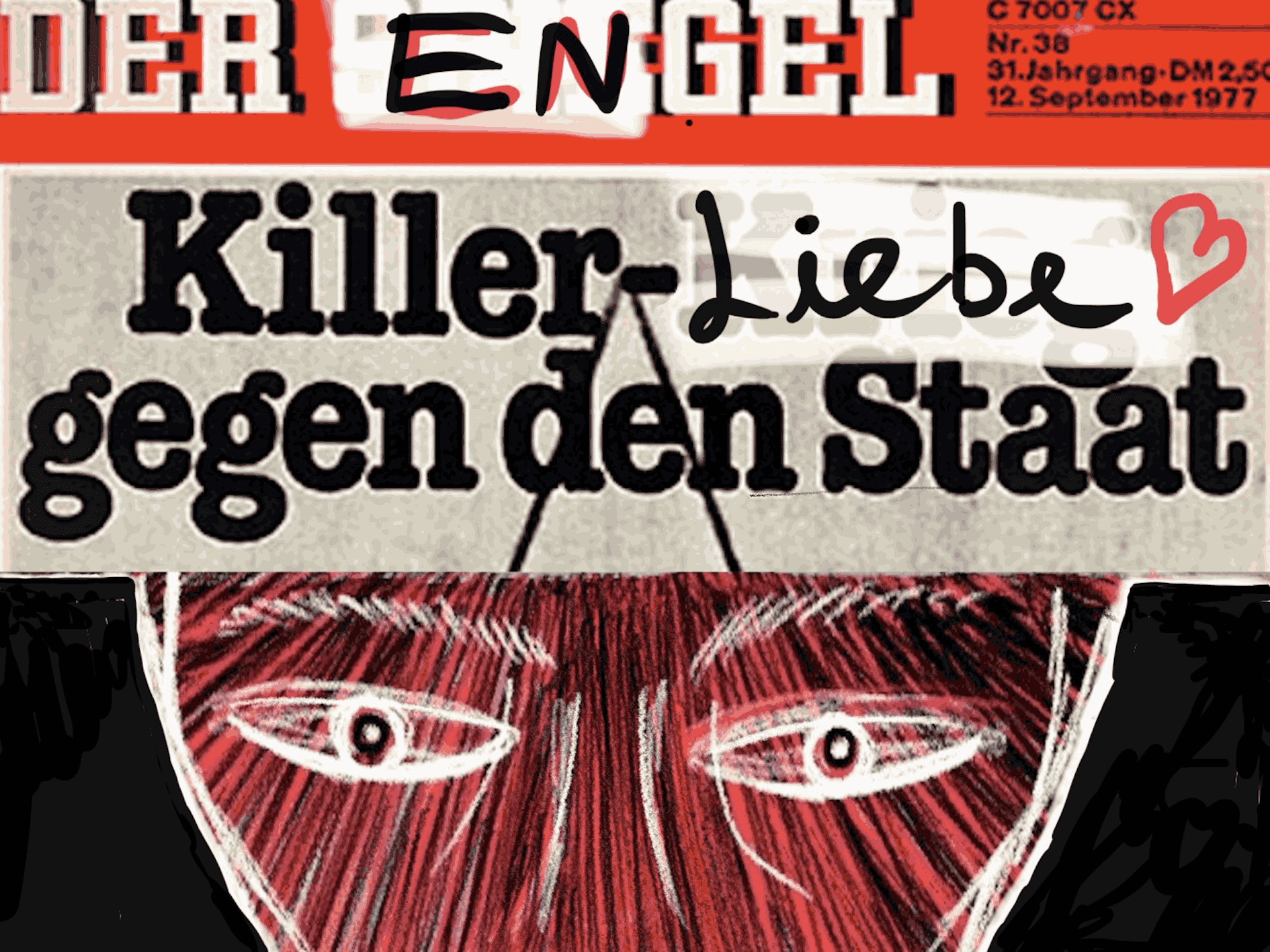

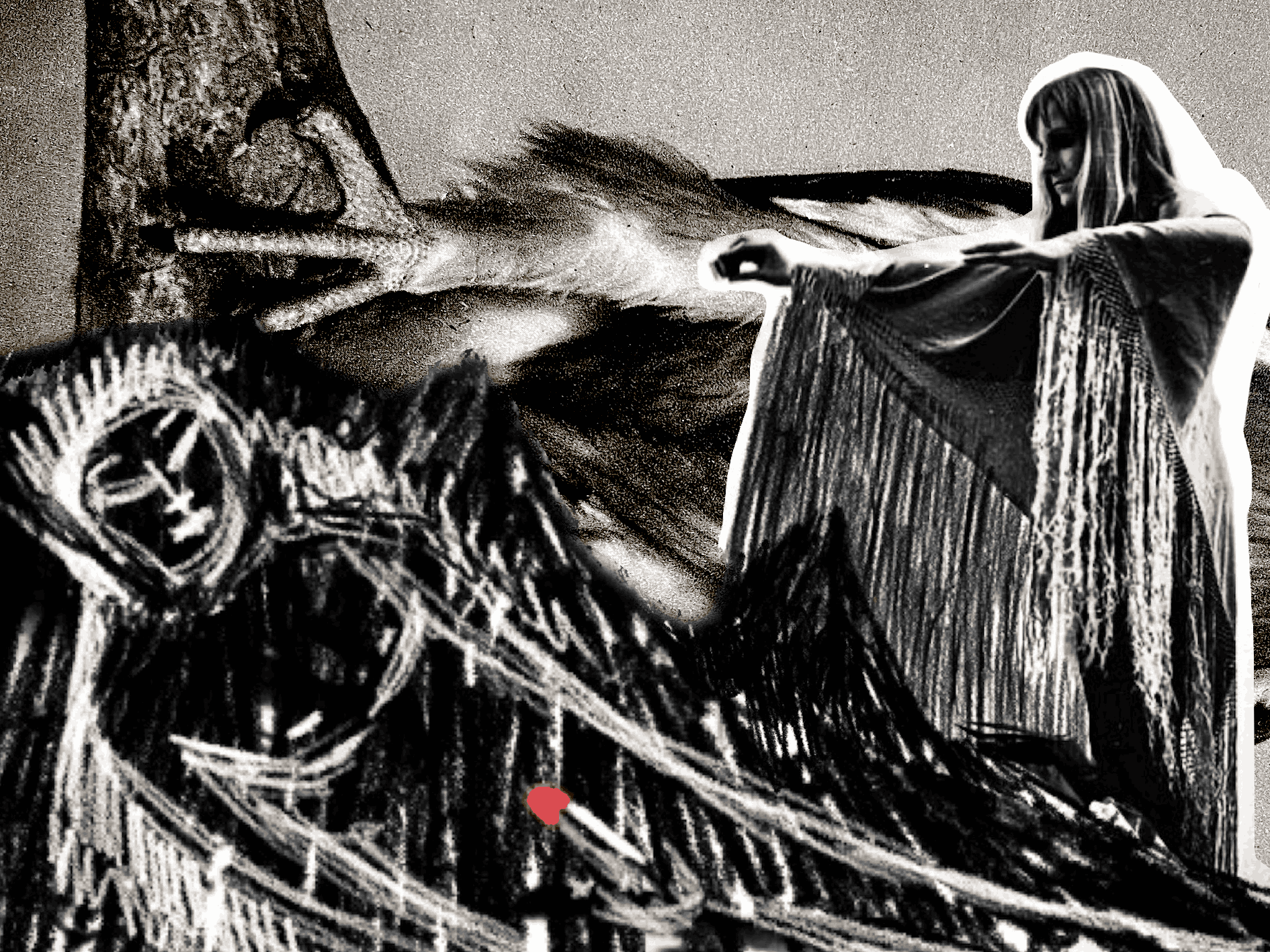

Recently, the press ISOLARII published Sjón’s Under the Wings of the Valkyrie (2023), which explores the interplay between eroticism and extremism via an architect’s obsession with Gudrun Ensslin, a member of the Baader-Meinhof gang, after a strange sexual encounter on a beach. Though brief, even for Sjón’s typical brevity, this intense narrative is as unshakeable as a fever dream.

SHANE ANDERSON: First of all, Under the Wings of the Valkyrie is a wonderfully strange book. Congratulations. It’s just been published in English for the first time but is in fact an early work of yours, right?

SJÓN: I would say it was written at the beginning of my proper life as a novelist but it’s not an early work since I started publishing in 1978 at the age of 16. I wrote Under the Wings of Valkyrie in 1994 right after I finished the first volume of Codex, 1962 (2018). It was published in Icelandic just months after I finished it as part of an anthology of erotic short stories. Most of the other works in the anthology were quite conventional, at least in comparison to this story, which really takes on the transgressive tradition of literature to the full. You see, when I was coming into being as a young writer, so much of what was required reading was transgressive—William Burroughs, Jean Genet, Kathy Acker, Dennis Cooper. If you wanted to be a real writer, you needed to nurture your transgressive side.

SA: And how does this transgressive, sexualized story fit in with the rest of your work?

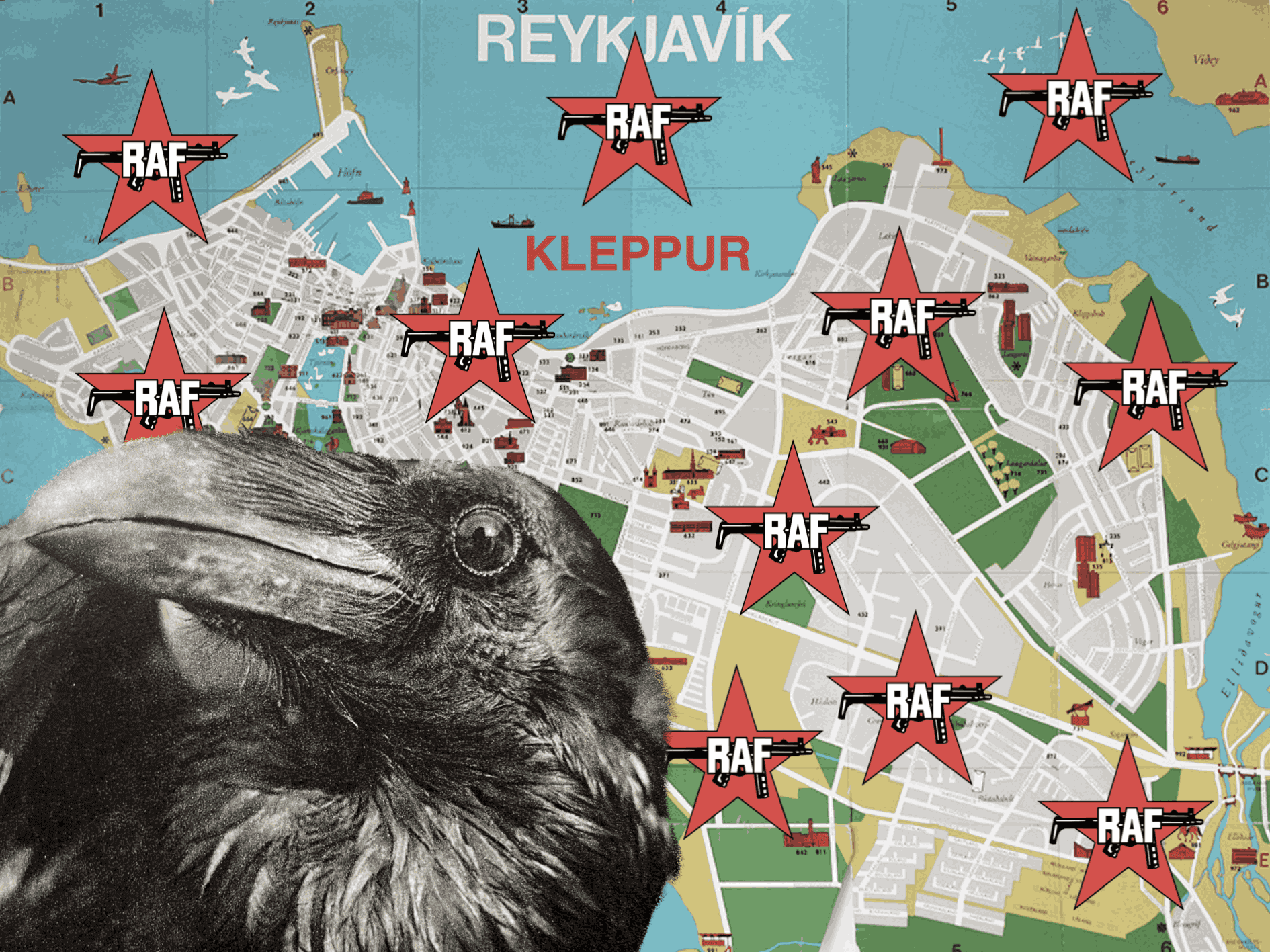

SJÓN: I think it fits in very well as there are two themes that are consistent with most of my novels. The first has to do with a powerless person who is not involved in history but is somehow reacting to the big story, which is often in the background. You might say that this is the Icelandic condition. As a country on the edge of the civilized world, we sometimes say we live north of war or north of history, because none of the major historical wars came to our shores with the exception of World War II. All the other wars were like background noise for the people living on this island in the North Atlantic. And I think that’s informed how I deal with history, and how I place my characters on the edge of historical events who are nevertheless affected by them.

SA: That reminds me of Halldór Laxness’ Independent People (1934), which feels very contained on Icelandic land until World War I breaks out and you see how the characters are affected. But to me, there’s a great difference between your work and his in that your novels seem much more invested in the world beyond Iceland.

SJÓN: That might have to do with me being born in 1962 and growing up in the 60s while international media was coming into being. I remember when my mother bought a television and some family friend—my mother was a single mother—carried that heavy thing into our small living room. The image was just grainy snow until someone started fiddling with the antenna and all of a sudden, I saw some Nazis goosestepping in Vienna. I kid you not, that was the first image I saw on our television.

Also, I became a big reader at a very young age. I would even read newspapers, journals, and magazines, which made me aware of many things happening in the world that other kids at eight might not even be able to imagine. I still have this picture I made in art class in 1970, and it’s of a demonstration with a group of people holding signs and pickets. I remember the teacher asking me what it was, and I told her that it’s a demonstration of students against teachers. [Laughter] It was just something I saw on the news or read about in the papers, and so you could say I was interested in what was going on in history and the world from an early age. I just thought they were exciting stories.

SA: Do you think that writers and artists today should address our (historical) situation and not create pure fantasy?

SJÓN: I don’t think it’s an obligation but for me it’s a way of acknowledging that 99 percent of people are powerless against the forces that form their lives and that they continue to live their lives in even the most extreme circumstances. Take for example the first part of Codex, 1962 with the chambermaid living in a tiny town in northern Germany during the Third Reich. She is just trying to live a normal existence while crazy things are happening. You know, you might be living under tyranny but still want a cinnamon bun. There’s something about the tension between the private existence of individuals and historical chaos that fascinates me.

SA: What’s your research process like?

SJÓN: Since I like to take my stories beyond what people consider real, I think it’s important to have a firm footing in “reality.” I do quite extensive research, trying to understand the broader picture, and I can be quite pedantic about what I learn. In Moonstone (2013), for instance, there’s this side story of a kid going to the cinema all the time, and I did very thorough research about what was playing in Icelandic cinemas from 1913 to 1918. If I mention a film being shown on November 5 in the center of Reykjavik, you can be certain that this was the film they showed.

From there, I start looking for what really excites me, which are usually the more eccentric or deviant manifestations of the times. In this phase, I try to let the historical facts inspire me. In Under the Wings of the Valkyrie, for instance, Gudrun Ensslin really did go to a PLO training camp. And in the fever dream when the narrator refers to his penis as Moby, this comes from the RAF using Moby Dick (1851) for codenames.

SA: In your work, very real events provide a framework for the events that are more mythological, surreal, dreamlike, or epic in nature. How do you see the relationship between “reality” and “fantasy”?

SJÓN: The boundaries between the real and the—no, I don’t like to talk about the “real,” realism weeds everything out. Let’s say between the material and immaterial… Anyway, I was a teenage Surrealist and one of the key elements I took from Surrealism is that we live in a constant encounter between the inner and outer reality. We walk through life in our material bodies, but we’ve got our minds full of something else, and we’re processing the world with the tools we’ve been given. And there’s no limit to what humans have tried to use to explain what the hell is happening here on Earth. And so, that brings us back to the second thing that unites Under the Wings of the Valkyrie with the rest of the work: it’s always about someone with ideas about things. So, there’s the historical events, the focus on the individual, and the individual’s mind interacting on the page. Take for example this book, where the main character has had a strange sexual encounter with a patient from a mental hospital on the beach at the age of eight. When he comes into puberty, things become strange as he starts trying to process what happened. The answer he finds is that it was Gudrun Ensslin’s presence in his life that did it and that she’s a succubus. This then leads to a monologue on demonology, which is an old tool to understand the world.

SA: Would you say then that life is inflected by the stories we tell?

SJÓN: And all the systems we’ve created. We are still living with ideas that are thousands of years old. You have whole institutions like the Vatican working with ideas that originate in the Middle East around year one. And if the Pope, the most powerful man in the world, doesn’t believe in demons himself, he’s got someone very close to him that does. So why can’t a guy in Iceland in the latter half of the 20th century not believe in them as well? It shouldn’t be so strange that the character leans on demonology to explain what’s happening to him.

SA: Do you believe in demons?

SJÓN: In Iceland, there are elves, which are a kind of a nation of hidden people living in the mountains and hills. I don’t believe in them personally. But I do believe they are somehow a manifestation of natural powers. It could just be magnetic fields—Iceland is a volcanic island and there can be disturbances to the magnetic fields that can influence the mind—but nature is speaking to us in a way that we don’t understand. There might be very rational explanations for it. But elves are how people have been able to give words and images to the experiences they’ve had.

I hate to admit it because there’s this whole romantic idea about us Icelanders, but it’s a fact that there are many elements from the old religions, old beliefs, old folklore that are still with us. This is especially true when thinking about dreams. There’s a widespread belief here in the power of dreams and they’re an important factor in our lives. This goes all the way back to the Icelandic Sagas, those great prose narratives that are sometimes about mundane things such as legal disputes and landownership, where the writers felt like they couldn’t tell the whole story without including dreams, premonitions, or people looking up into the sky and seeing blood dripping from the hooves of a horse. And so, for me, it was like, of course I’m going to include all those elements, why shouldn’t I bring all this in? Because that’s what’s happening on some level.

SA: From what you just said, it sounds like your writing style is akin to a 21st century version of the Icelandic Sagas. How would you describe your writing style?

SJÓN: I never wanted to call it magical realism because it seems to me that many writers who call themselves magical realists or who write in that style seek the strange out and push it into the foreground, but in my writing, it’s simply there. When there’s a need for something strange, I bring it in. But if there’s no need, I’ll leave it alone for 50 pages. I’m not looking for it, you know?

SA: Would you say that you just follow your subconscious? Is this still an expression of your Surrealist youth?

SJÓN: What I learned from Surrealism is to be a good listener to my subconscious. Surrealism is a training to hear the strange little voices trying to find their way out. But nothing I write is anywhere close to Surrealism’s technique of automatic writing. In fact, I write very, very slowly. It takes a long time before I even start writing anything. My books are very constructed—which is why I try to make the narrative feel like it’s flowing—and I really work with the construction and structure of them. Ideas can roll around in my mind for a long while, and I’ll maybe write one page or half a page, a single paragraph, just to make a test and see what the text could be like. And then when I do start writing, sometimes I have to stop after I realize the story is going in some new direction. Then I have to go back and do the research. I have to get things right before I can keep going. But unlike many other authors, I don’t do many drafts. I more or less do only one. I go at the page for days and days to get it right. Mostly to get it to sound right. The sound of the text is really important for me. I would be happy if I could write faster and more flowing but it’s really a struggle for me.

SA: Speaking of struggles, RAF plays a central role in Under the Wings of the Valkyrie and I’m curious as to how this came about.

SJÓN: When I wrote this in 1994, the days of urban guerrillas and radical left terrorist cells suddenly felt like they were behind us. No one anticipated a new wave of terrorist attacks that would begin with the Oklahoma City bombings just a year later. But things were different in my youth. There was the IRA in Ireland, the ETA in Spain, RAF in Germany, and Brigatte Rosse in Italy. I grew up with this presence of radical terrorist groups. And there was a strange fascination with them. Icelandic people in the radical left sympathized with Baader Meinhof and their struggle as well as with the struggles in South America, Southeast Asia, Cuba, and all the movements around the world. And so, when Baader Meinhof performed their attacks, people in Iceland were like: “Why not? We need this here too. We need to strike and fight against world capitalism.” Today I don’t think you’d find the same sympathy we had for terrorists.

SA: It’s a bit more than sympathy though, right? I mean, the narrator in this book has sexual fantasies about a terrorist. But tell me: sex often plays an important role in your work, doesn’t it?

SJÓN: Well, you know, it’s there. It happens. And it has always been part of how I tell a story. Again, coming from the background of Surrealism, when you have the inner reality meeting the outer reality, the body is the meeting point between them. The body is where the problems start. Love, desire, and seeking pleasure are such amazing manifestations of the forces inside us that we’re unaware of. And they’re also amazing because they place us in the same sphere as animals.

As for the sexual elements in Under the Wings of the Valkyrie, well, that’s just what the story demanded. I always follow that and go on a journey of discovery with the characters.

SA: This story or novella is very short—even in comparison to the rest of your work, which is known for its brevity. How did you settle on such short forms?

SJÓN: I think it might come from being a poet first. For the first five years of my writing life, I was a poet, and then when I started writing prose, I just discovered that this was the way I write. I learned to accept that—and that there’s nothing wrong with short books. The [French Nobel Prize Winner] Patrick Modiano is a writer of small books. In fact, I consider myself lucky to have found a form that works for me and that my publishers and editors here in Iceland have never tried to push me to write longer novels. The project I’m working on now is actually something that will be longer than my last three books but I’m approaching it as a writer of short books. There was one time when writing a short book was a conscious decision from the beginning, and that’s Blue Fox, where I felt like I needed to pare everything down. That book needed to be an anti-epic. It’s an anti-Independent People, you know?

Credits

- Text: Shane Anderson

Related Content

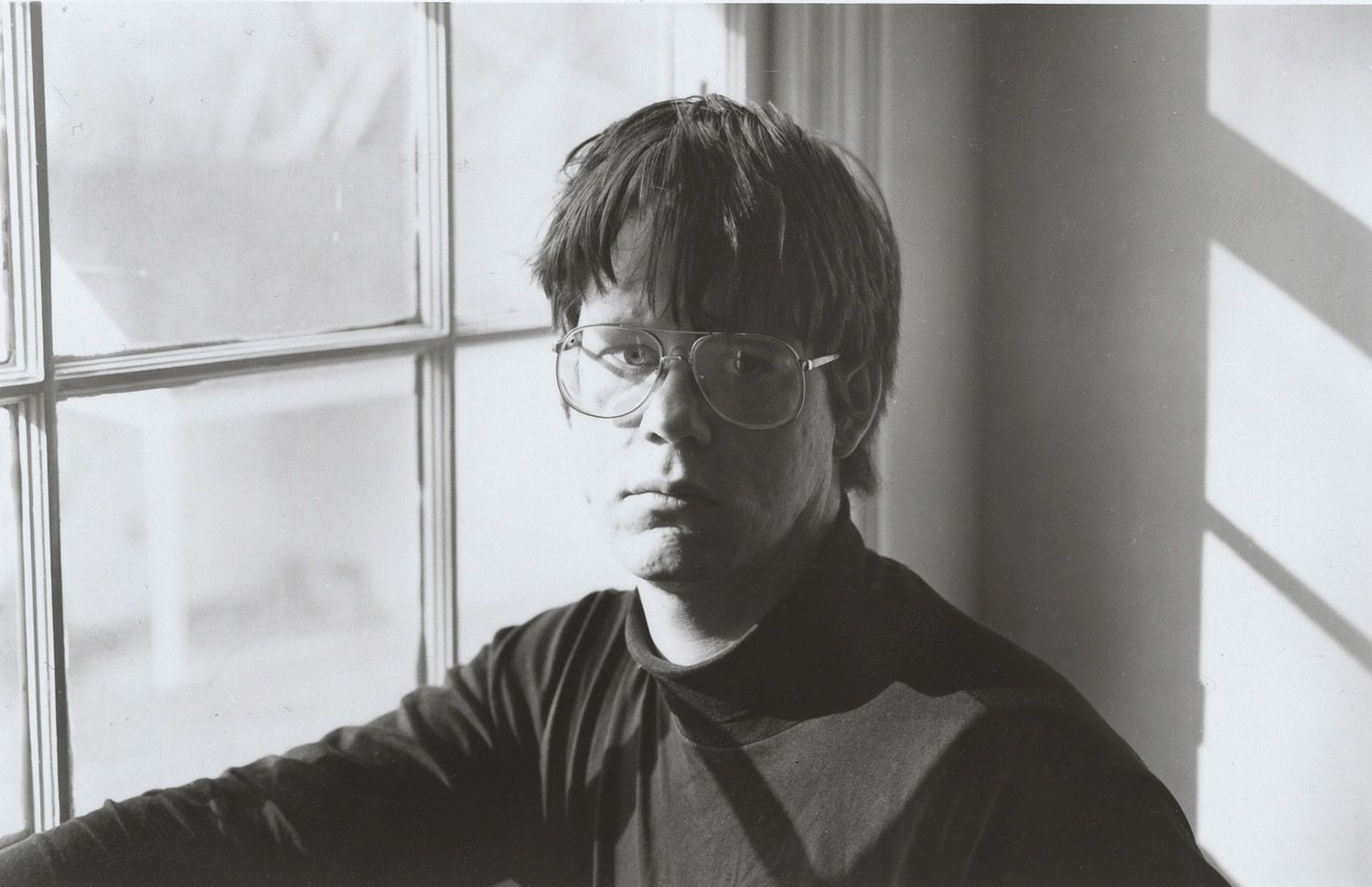

Mining a Counter-History from the Past: WILLIAM S. BURROUGHS and Subcultures in Kansas

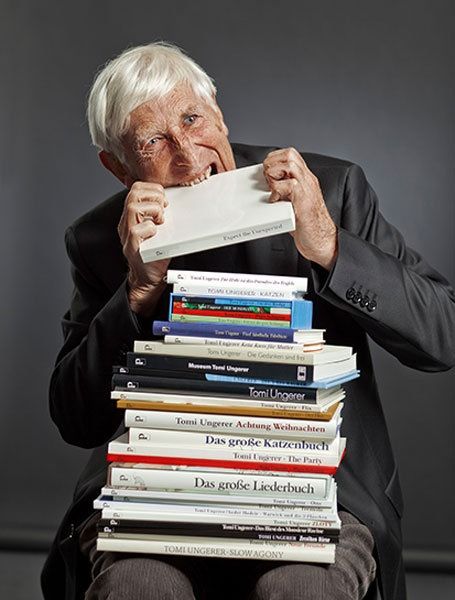

TOMI UNGERER (1931-2019): Waiting for Godot

WILLIAM T. VOLLMANN: She Who Is So Lovely Is Drinking In That Loveliness I’ve Drunk

ALEXANDER KLUGE: Writing Attitude

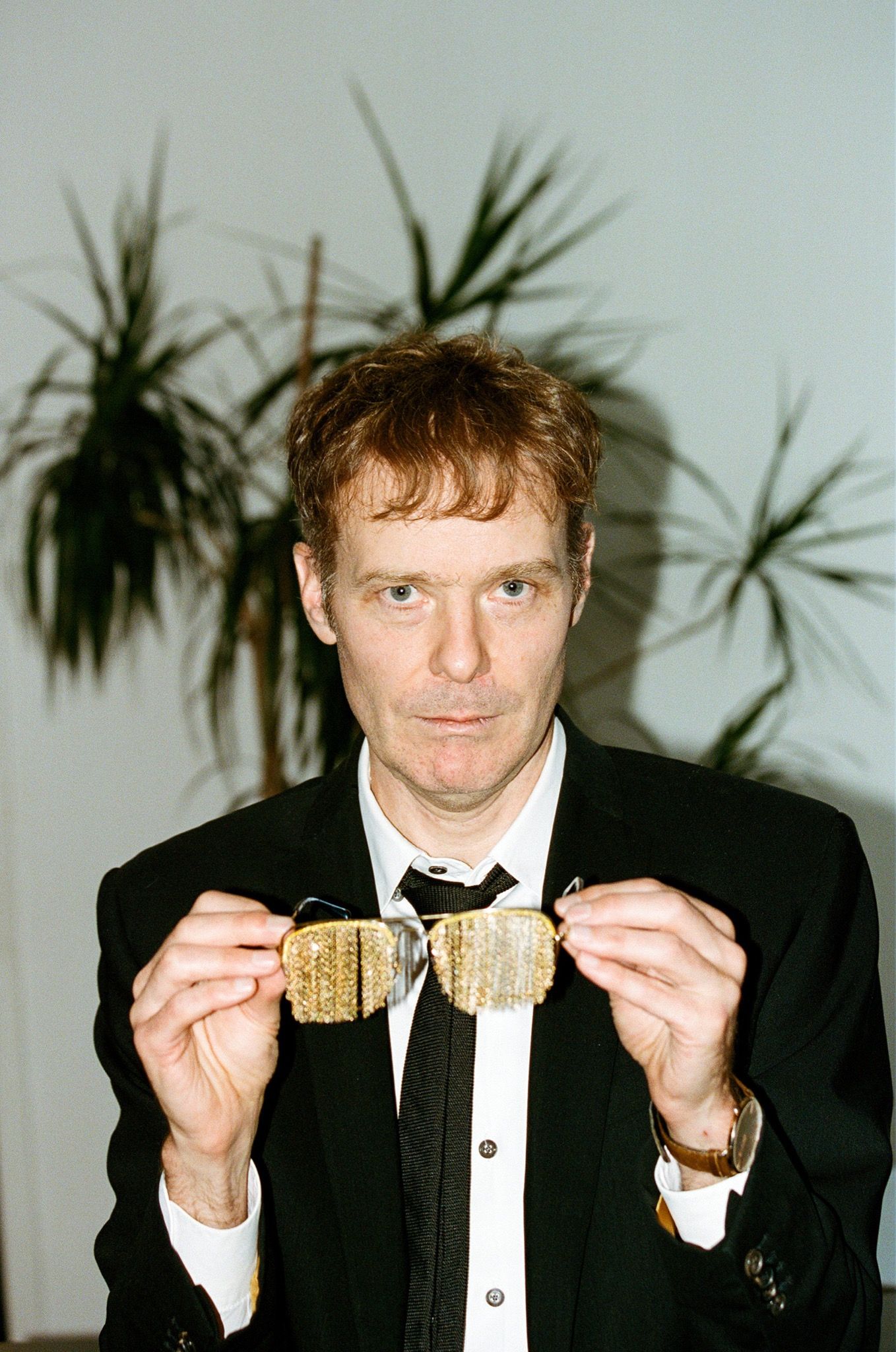

TOM McCARTHY Incarnate

VIRGINIE DESPENTES: Hates People, Loves Dogs.

MICHAEL POLLAN Changes His Mind

Never Born, Never Dying: EILEEN MYLES