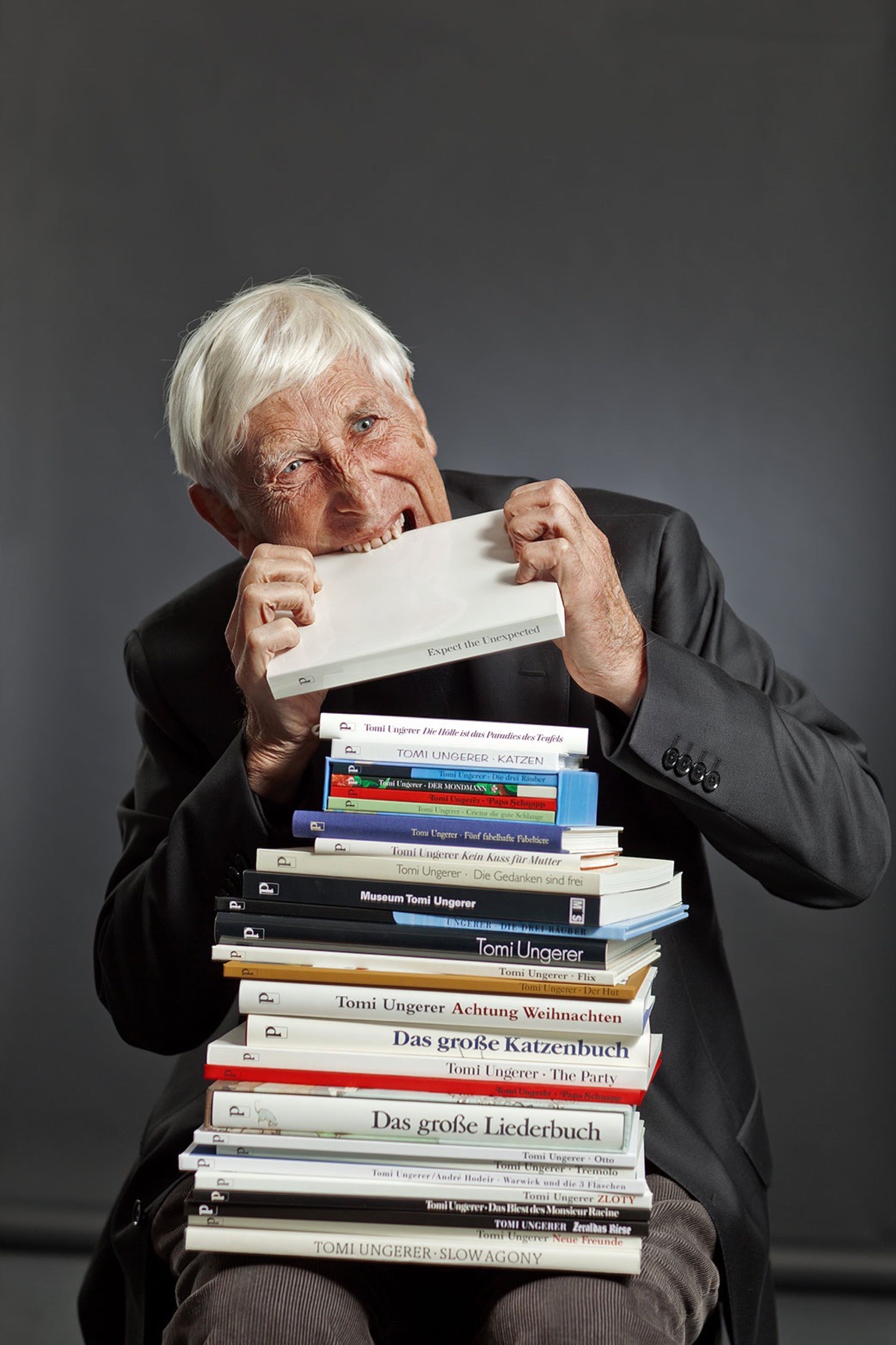

TOMI UNGERER (1931-2019): Waiting for Godot

Illustrator and author TOMI UNGERER was born on November 28, 1931 in Strasbourg, France, the capital of the Alsace region located on the west bank of the upper Rhine. The youngest of four children, Ungerer lost his father – an artist, engineer, and astronomical clockmaker – when he was three years old, and was raised by his mother and uncle. “I’ve always had the feeling,” Ungerer says, “that when he died, he passed me all his talents, just like that.”

And then came the war. The Nazis began to occupy Alsace in 1940, when Ungerer was just nine years old, and he was prohibited from speaking French and forced to learn German in three months. Because of his artistic talents, he was conscripted by the Wehrmacht as a young illustrator – his first assignment was to draw “a Jew.” He saw his first dead person when he was 10, his neighbor Mr. Hermann. A self-proclaimed paranoiac, Ungerer has never been able to get rid of his fear of the war. “Death,” he says, “is perhaps the subject I’ve used most in my drawings.”

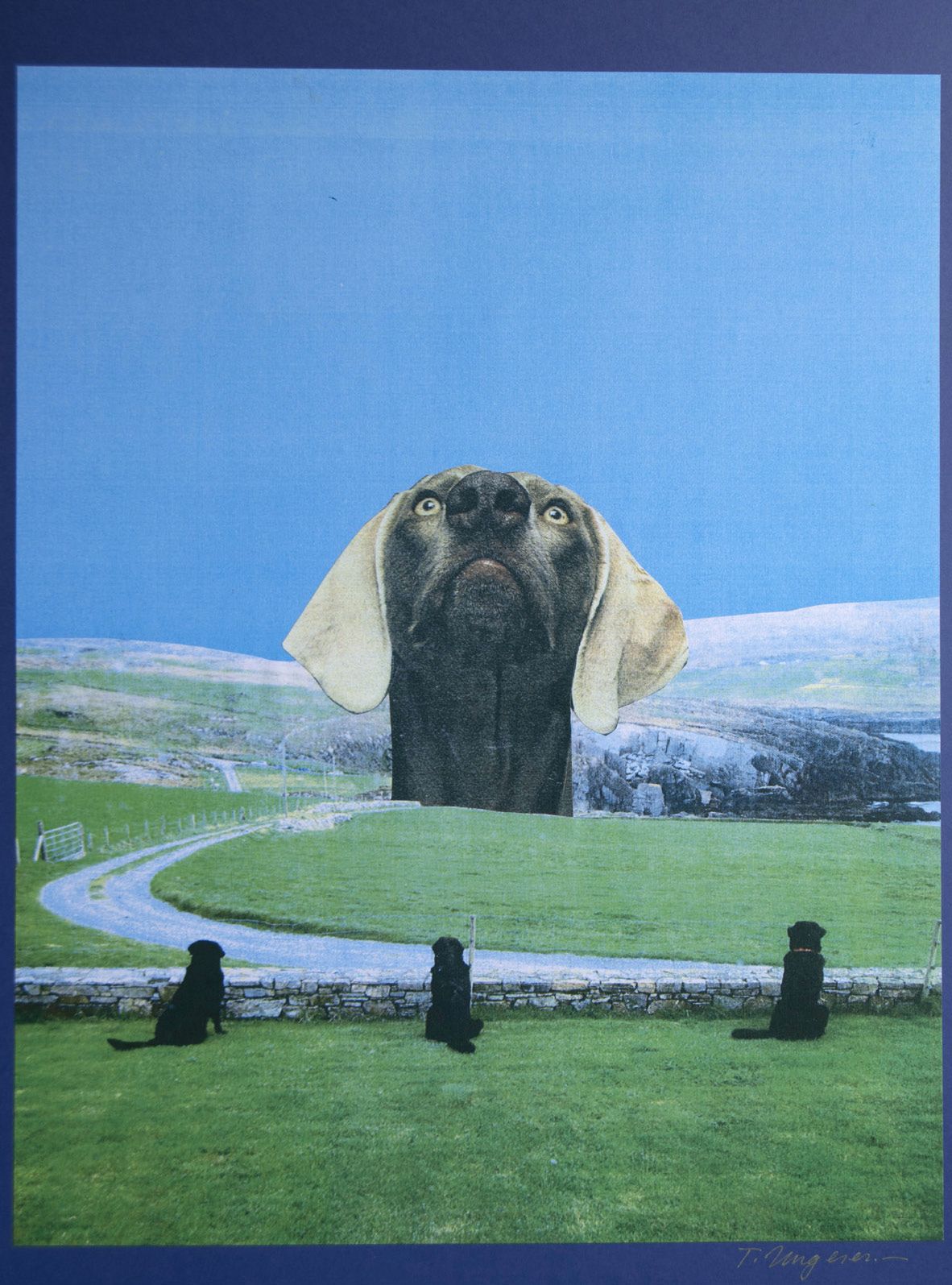

In 1956 Ungerer went to New York, where he instantly became an award-winning children’s book author, graphic designer, and illustrator for newspapers and magazines, and a leading figure in the world of advertising. He also made some of the most imaginative erotic art and adult literature to date, for which he was interrogated by the FBI, banned in American libraries, and forced to flee, first to Nova Scotia, in 1972, then later to Ireland, where he’s lived with his wife, Yvonne, for the last 37 years.

The recipient of numerous prestigious awards, including a European prize for culture and a Hans Christian Andersen Award for children’s literature, Ungerer is also an officer of the Légion d’honneur and a Council of Europe goodwill ambassador for childhood and education. He’s published more than 150 books, many of which are finally being reprinted, and is the only living illustrator ever to have a museum dedicated to his life and work. For Tomi Ungerer, far out just isn’t far enough.

Good morning, Tomi.

Good morning. I have to say that this morning I’m in a bit of a daze. Yesterday I had one of my days. I wrote all day for 12 hours and to keep on going I drank. I’m a bit fuzzy here, but I’ll just act according to my competence.

You’re a prolific writer, Tomi, which not many people know.

I love to write and I love words. It’s a three-language passion, because words bounce from one language to another and come back with another meaning. For me, a dictionary is like an alembic.

What’s that?

You know, what sorcerers used for distillation.

A device to distill magic.

Yes, exactly.

What are you writing now, Tomi?

I always write in three languages. When I take notes I use one part of the page for English, one for French, and another for German, and it goes back and forth. I have a busy mind. The other day I was writing two short stories at the same time on two different sheets of paper.

In two different languages?

No, when I write a short story I normally stick to one language, unless there’s an equivalent that I can’t find right away.

Do you use each language for a different purposes?

That’s a very good question. I think I use English for humor, French for wit, and German for feelings. In a way it’s like the Three Faces of Eve.

Like multiple personalities.

That’s what I like.

French is very dry.

I like that too. In English there’s a profusion of synonyms. You have about five or ten words for one French word. I must say English is really ideal for playing around.

You can’t be as funny in French as you can in English.

That started after the renaissance when they cleaned up their act.

There’s an interesting book called The History of Shit, which talks about how the French language—l’Academie Française—was institutionalized the same time Paris set up its sewage system.

I love Old French because it was still a free-for-all. Today it’s the precision—the absolute accuracy—that I like about French. It’s more a crystallization process. In German you can put any two words together. If I can’t think of a word right away I can make one up.

How do you manage to work in so many different mediums?

I can’t even figure it out—it’s nearly impossible. I’m like a bee going from one flower to another. I’ll be working on a sculpture and then I’ll have to write something down and then on to something else. I just have to live with it, right?

But you also have to get it out.

It’s much more difficult to break through when you’re in so many different things.

Let’s talk about mechanics. You use mechanical elements in your children’s books–in the Mellops series there is a machine that can distill petrol from grass.

I’m just very mechanical. A whole part of my life involves invention. I designed what I call the Wheel of Energy for the French EDF [Électricité de France] in 2010. It was designed for the Shanghai World Expo, and it’s basically a mechanical animation of erotic frogs. Because sex is basically mechanical, in motion and position.

How does the Wheel of Energy work?

You take two rafts and put a watermill between them and anchor it. It can work on rising and pulling tides, or you can put it on a river. It just generates energy, it’s mobile, and you can put it anywhere.

Speaking of motor coordination, your father was a watchmaker.

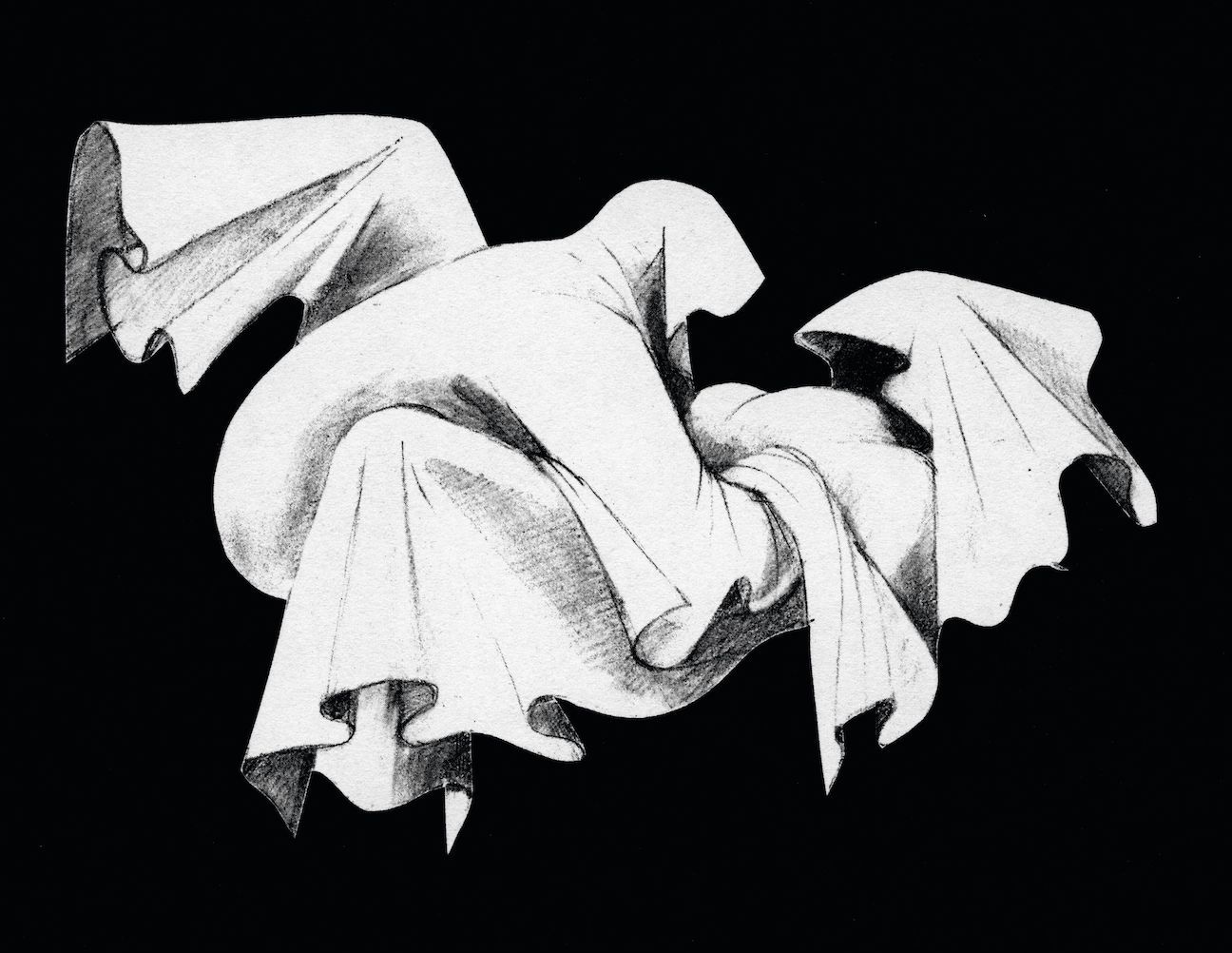

He was an artist and an astronomer, a humanist really. He built astronomical clocks—many public clocks in eastern France are Ungerer clocks. I have mechanical ghosts in my family. It’s really in my blood.

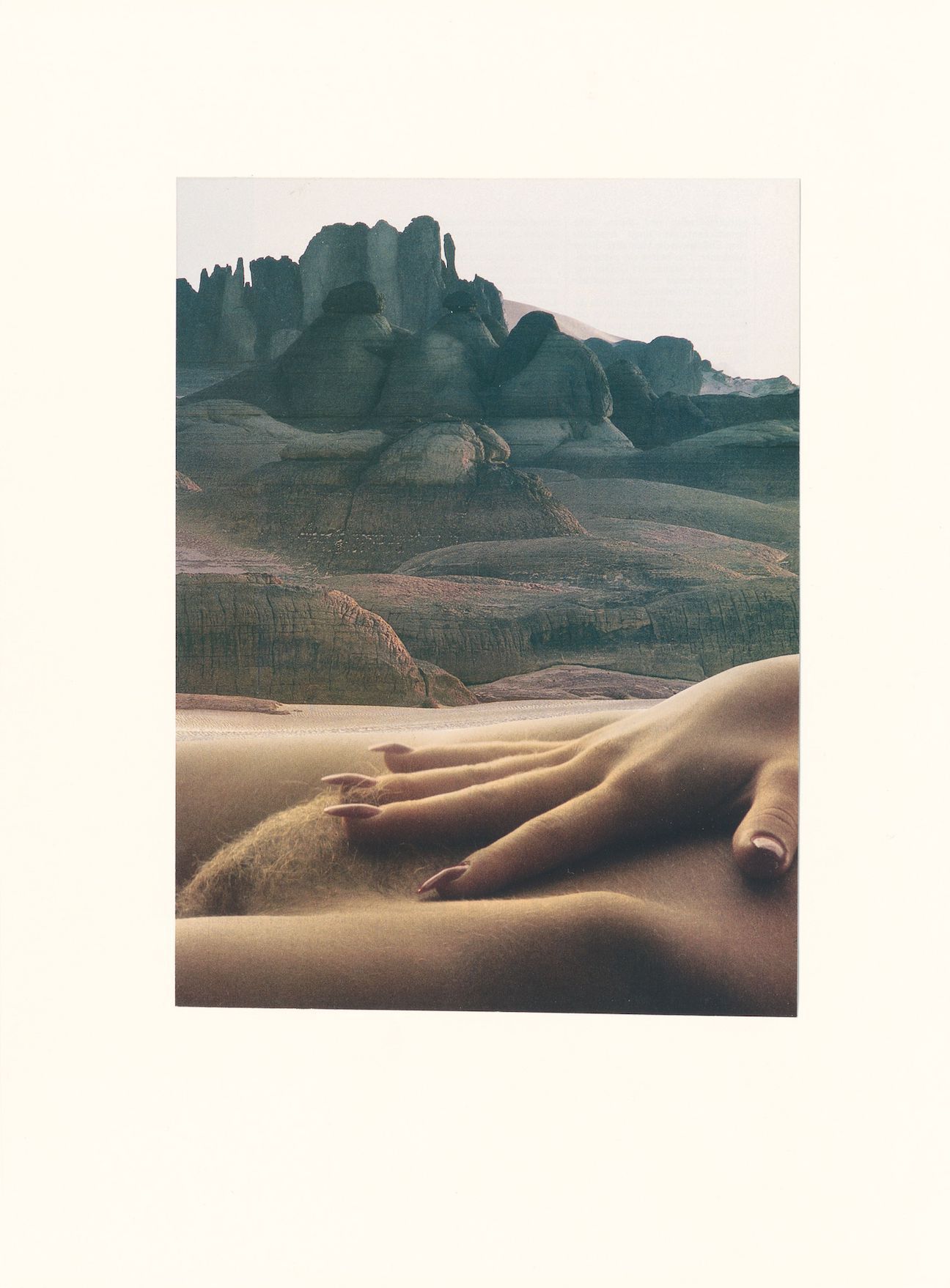

Your book Fornicon (1971) is about simulating sex with machines.

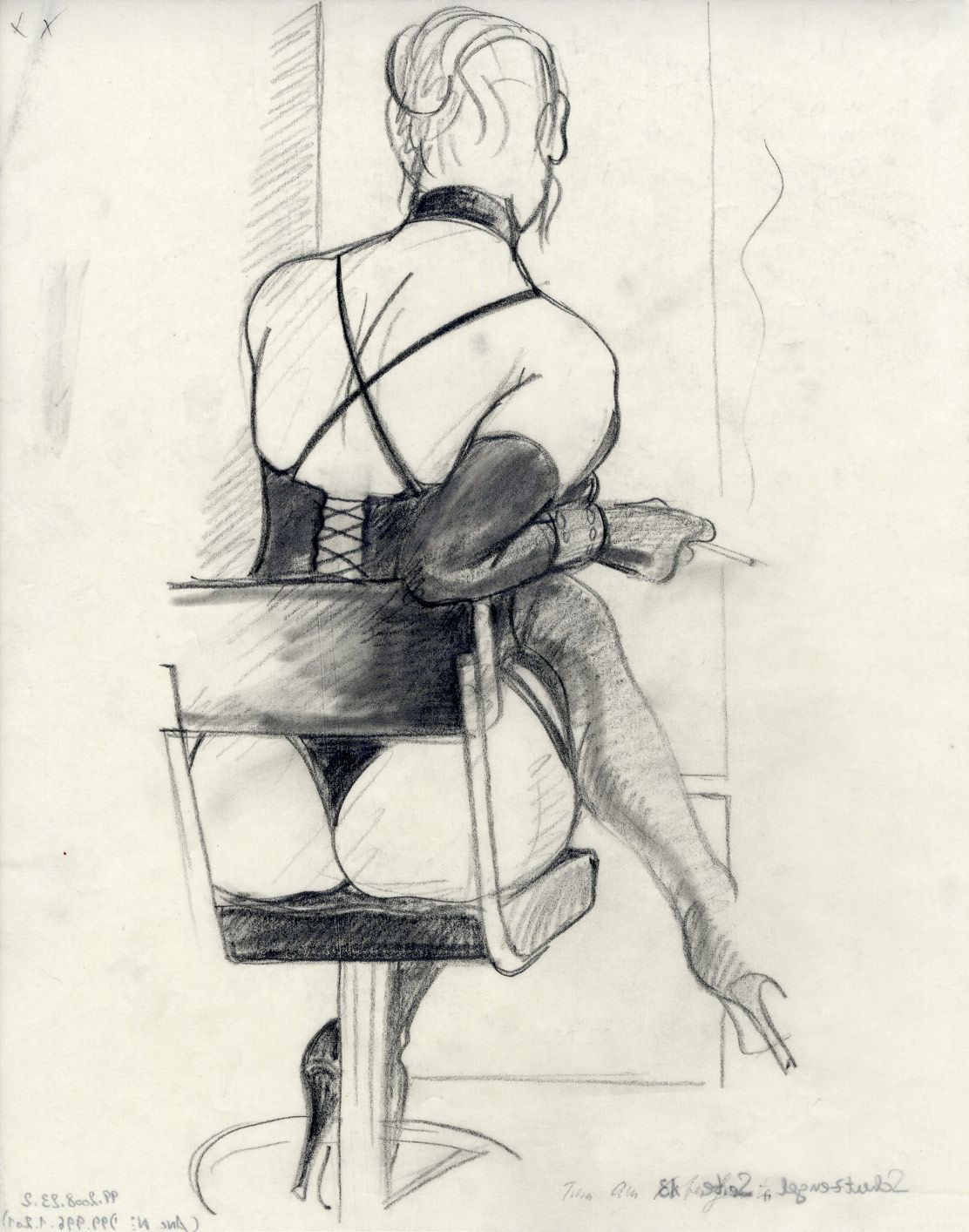

That’s right. I actually built some of these machines working with Barbie dolls. My other book Schutzengel der Hölle (1986), or “the guardian angels of hell,” is about dominatrices in Hamburg. It hasn’t been published in English, but it documents a form of specialized prostitution: the mechanics of fantasy, if you will. I lived in the bordello as a bystander, just recording its daily functions. I wrote the book but the drawings are also very thorough.

It’s a much more sociological work.

But on an extreme subject. They were wonderful women. Being a dominatrix is not a profession, it’s a vocation. It was first time in my life that someone told me they told me they vomited while reading a book. It’s really rough stuff. One dominatrix named Astrid had a customer who couldn’t come that often because he could only have an orgasm if he had his fingernail pulled out with a pair of pliers. No doctor or psychiatrist would do that. They were wonderful women!

Do you see it as a form of therapy?

These guys have an obsession, and where are they going to go with such an obsession? It’s better for them to have an outlet than kill a little girl or boy in the woods. I think bordellos have a function, though it was even hard for me to take some of it. As a matter of fact, Dr. Eberhard Schorsch (1935–1991), who was the head of the Deutsche Gesellschaft für Sexualforschung (German Society for Sex Research), told me it’s the most thorough and complete book ever published on the subject. You have to live there [in the brothel] to get this kind of material. The prostitutes have to trust you. There was another guy who could only have an orgasm if his tongue was nailed to a block of wood. The first line of my book is “Was ist normal?” It’s absolutely relative.

What was your first encounter with erotica?

When I was seven years old I found two girlie magazines behind my father’s books. It was the first time I was exposed to this kind of thing. When I looked at the pictures I realized that my father had gone over them with gouache.

He modified the photographs to match his pleasures?

My father didn’t like big-breasted women so he went over all the girls, retouching them to make them smaller. He was an aesthete. But I got into eroticism as an exorcism of my puritan upbringing. After my father died when I was three, I was raised Protestant by my uncle.

High expectations of moral behavior.

Morally I believe that everybody should be allowed to do whatever they want as long as they don’t hurt anybody else. Unless it’s sadomasochism and then it’s by mutual consent. What I always found fascinating in eroticism is that when you meet a woman you find out what her fantasies are. And according to her fantasies you just perform and you stage. And it’s a tremendous game. I knew a person who was aroused by medical examinations. So let’s play doctor!

What’s the difference between eroticism and pornography?

I’d say it’s the same difference between men and animals. Any animal can give you a lesson on how to do just plain sex, but eroticism is more an intellectual process, a distillation, a careful staging. It’s a way of putting into action your fantasies. It’s a long ritual. For me pornography is not erotic. I sometimes think it’s rather funny or even ridiculous.

Do you think that political satire and eroticism are connected?

They have always been very close together, not only political satire but social satire as well. When they celebrated the anniversary of the French Revolution in France, I made an erotic political satire. Napoleon Bonaparte started as a young general for the Republic, after the revolution, and where did he end up? As Napoleon the Emperor of the French. So I made a drawing of the Emperor taking Marianne, the French symbol, from behind. I was accused of depicting sodomy, but it’s not. You can take somebody from behind consensually.

How do you view humor in relation to fear?

I think humor is the best medicine against fear. Sometimes during the bombings in Alsace my whole family would just laugh away. My mother was fearless. And just the other day, a woman came to visit me in the studio and she saw a skeleton I have there. She said, “About twenty-eight years ago I came to visit you—I was six years old—and I was terrified of the skeleton. You told me the skeleton was your mother and asked me to go shake hands with her.” She overcame her fear of the skeleton. Then I told her it was a joke, because otherwise it would be a lie.

When you moved to the States you were really misunderstood.

My whole life has been about proving reality with the absurd. I’m fascinated by the absurd. I cultivate it, I practice it. And one of the most absurd things I realized when I went to America was that in the land of blues and jazz there was racial segregation—and it was immediate outrage for me. I couldn’t understand the irony. The Americans came to fight Nazi Germany, the ultimate racist regime, and then I arrive in a country where racism prevails, especially in the era of McCarthyism.

How do you feel now going back to America?

America is really a land of contrast and contradiction, which explains all the hypocrisy. Let’s not forget though that there’s the United States of America and there’s New York, which is a completely different entity. I’ve never loved a city as much as I loved New York. Possibly Hamburg, but New York is unbelievable.

You were investigated by the FBI there.

I was kidnapped by the FBI, which was again so absurd! I even had the soles of my shoes opened up to see if there were secret messages. But after that I went back to America and New York two years ago. I was delighted. In New York—not outside of the city necessarily—there was racial harmony. To see that there’s one place where it’s possible made me very happy, because xenophobia is all over the world right now. I was born already as a child with a need and a love for peace.