WILLIAM T. VOLLMANN: She Who Is So Lovely Is Drinking In That Loveliness I’ve Drunk

|CARSON CHAN & MATTHEW EVANS

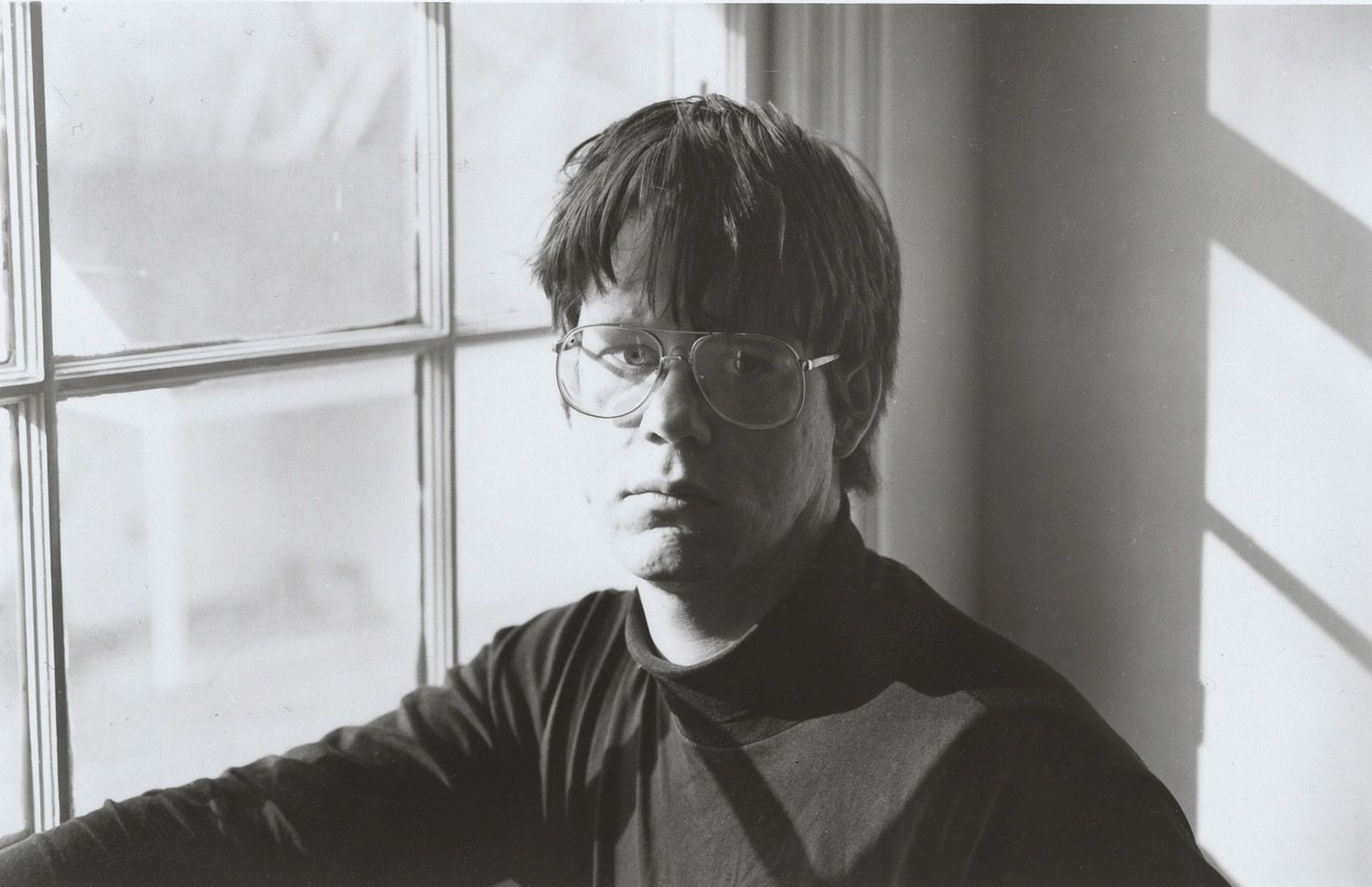

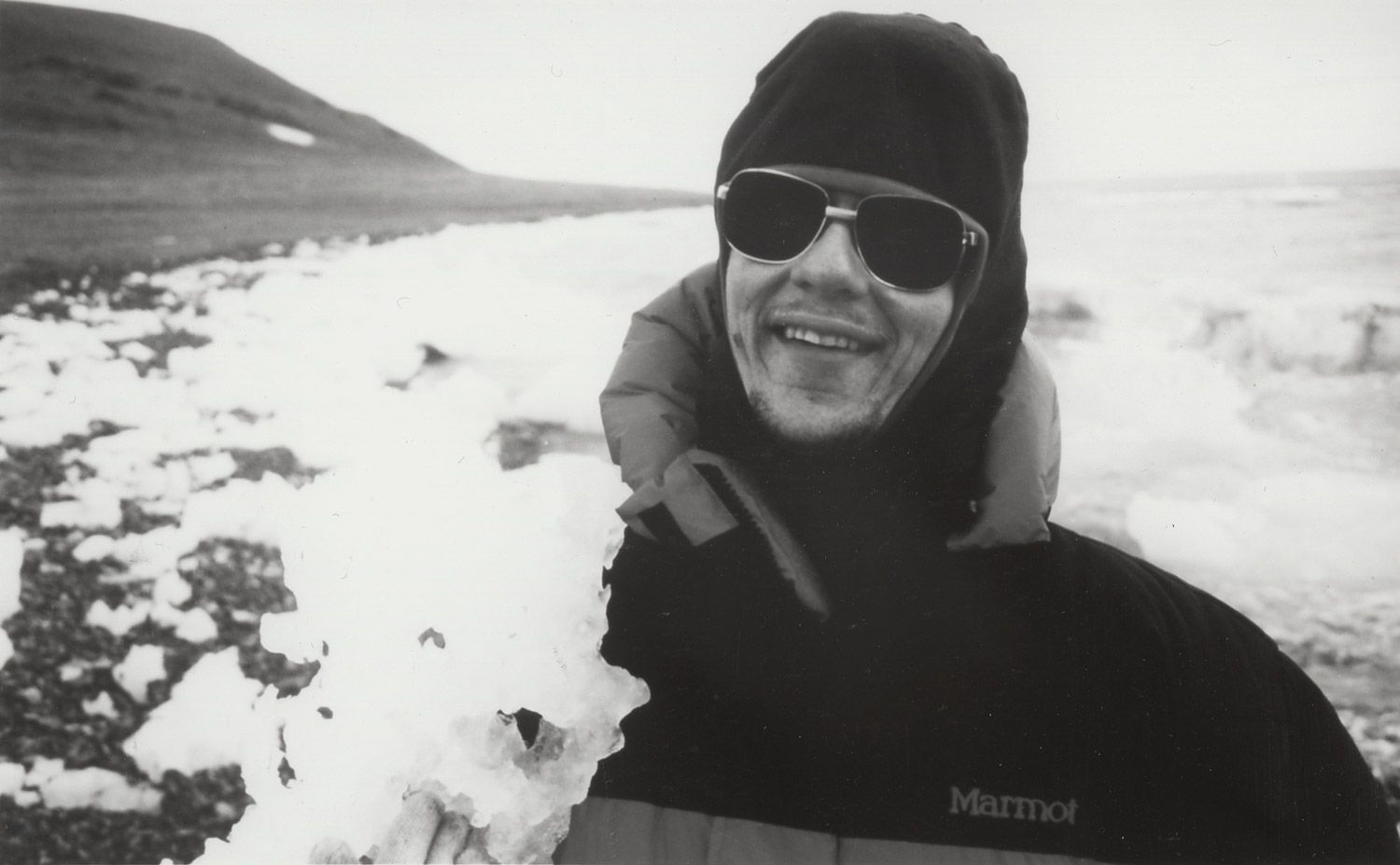

It is said that the American author WILLIAM T. VOLLMANN has a peculiar way with people, that his heedless sincerity in attempting to comprehend others is as startlingly foolish as his literary renderings of them are complex and involved. None of this we would know, however, because we’ve never met him. Vollmann didn’t want to be photographed and refused a live interview. So we decided to become pen pals.

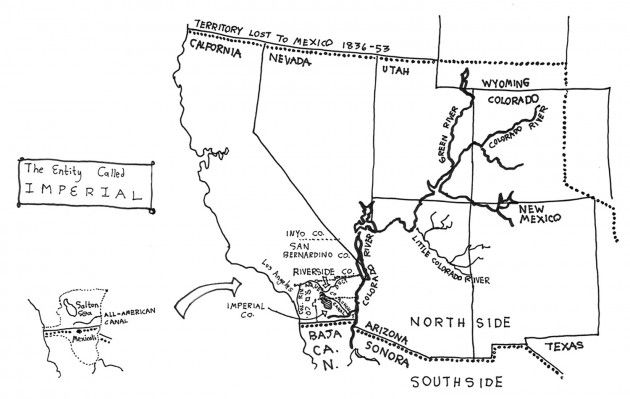

CARSON CHAN & MATTHEW EVANS: In Imperial, you write: “It may be that, since this southeast corner of California is so peculiar, enigmatic, sad, beautiful and perfect as it stands, delineation of any sort should be foregone in favor of the recording of ‘pure’ perceptions, for instance by means of a camera alone; or failing that, by reliance on word-pictures.” How do you view the finished work in relation to the field research you’ve conducted for it? Is Imperial the book capable of communicating the Imperial that is “perfect as it stands”?

WILLIAM T. VOLLMANN: Imperial, like Walter Evans’s and James Agee’s 1941 book Let Us Now Praise Famous Men, is simply an honest effort, and as time goes by, and Imperial alters as has the sharecropping South observed by Evans and Agee, my failures may indeed be slightly mitigated by the fact that both they and Imperial itself are farther away, more of a piece, both woven into the fabric of their time. I swear that if I had had more money and more years, I would have done better and more. How sad I feel not to have learned more about the various Indian tribes! How much I would have longed to send an army of spies into the maquiladoras for ten years!

You’ve mentioned that Imperial is America, and that Imperial is the world. One can’t help but wonder whether you chose this particular place as a symbol for “the center of the world” because of its name.

You have a point. What an eerie name, for Germans and Americans alike! Bismarck’s honest Realpolitik is more comprehensible to me than the strivings of American idealists who proudly rejected the hierarchicalism of the British Empire, thought themselves democratic and free, wrote a beautiful Constitution, which I will always love, widened the dreams of Wordsworth, Blake, and the French Revolutionists – and meanwhile cheated and hunted down Indians, tried to keep yellow and brown people in peonage, praised small, self-sufficient homesteads while proudly giving birth to giganticism … And none of this was hypocrisy. It was what Orwell would call “doublethink.” It was Imperial. on the Mexican side of the border, Imperial has a more pompous grandiosity. My friend Larry [McCaffery] always says that, for him, mexican Imperial is two great pillars and a huge sign and a driveway leading to an abandoned building site. On the American side, Imperial is a self-defeating idea of infinite individual enrichment. When the riches get big enough, the corporations come in. When the farms are rich enough, the price of farm produce goes down. And everyone takes water for granted, until there’s not enough of it.

What can we gain from trying to understand the world through Imperial?

“I long for my sentences to be beautiful and for the things which have moved me to be preserved for as long as possible.”

We can gain an appreciation of the beautifully and horribly arbitrary nature of delineation.

Does this project of mapping the world have failure built in as an outcome?

Of course any mind is finite and reality is infinite. Therefore, all of my projects must be failures. The more I hope to accomplish, the worse I must fail. But this is no excuse not to be ambitious.

Does admitting failure negate its effects?

Unfortunately not. However, admitting specific failures may help somebody else to improve upon my most egregious weaknesses, so that, over time, failure may be lessened – until further time passes, and my projects come safe into the harbor of irrelevance.

But it’s easier for your readers to see your books as masterpieces – works that demonstrate this unbelievable ambition and calculation – than not. What do you strive to achieve through writing books, and such lengthy ones at that, if not works of greatness?

I long for my sentences to be beautiful and for the things which have moved me to be preserved for as long as possible, for their own sake, not for mine. The loveliness of a sunny Arctic day, with mosquitoes singing in the moss and ice shining like rainbows, what can I do to memorialize this as the Arctic melts? The people I’ve loved, can I write them epitaphs before they and I melt, so that someday someone might wish to have met one of us? And now as I get old, and begin at last to see political patterns in their naked horror, I think: Can I record any of the lessons I’m learning, in hopes of sparing some future soul from making or suffering from certain mistakes?

Is the naïveté and lofty grandeur so present in The Young Man from An Afghanistan Picture Show becoming more difficult to engage after so many years of field research?

I expect less but hope just as much, and long even more than when I was young to do good.

What were some of the most striking differences for you in visiting Afghanistan in the early 1980s and then again in 2000?

In 1982, Afghanistan was an occupied country. I felt its fear and desperation as I came over the mountains with the mujahideen. We were vulnerable to enemy planes; there were bomb-husks everywhere. I admired the mujahideen who were willing to sacrifice their lives for their country and their faith. In 2000, the Taliban controlled most of Afghanistan. The parts I visited were safer and better off. There is no question that, for all their ignorance and repression, the Taliban were vastly superior to the Soviets, and probably better than the feuding warlords and bandits in the immediate post-Soviet years.

Would you ever write about a place without having been there first?

I would prefer to visit in most cases. But I could imagine writing about some fantastic or alternate universe in which anything goes. Such was the 19th-century America at the beginning of You Bright and Risen Angels [1987]. Such might be my vision of a Jovian landscape.

You purposely leave out autobiographical details in your books, yet there is an undeniable relationship between your books and your life. One particularly poignant example of this is the elaboration in The Atlas [1996] of your two companions’ death in Bosnia. Why did you choose to photograph them right away?

Because I knew that my gaze was not rational at that moment, but the camera’s was and always would be. I knew that later on I would want to look at those pictures and try to understand exactly how and why they died. I expected that the matter would be obfuscated by the forces which killed them, and I thought that the photos might be evidence of the truth, whatever that might turn out to be.

Why be objective?

Philip K. Dick wrote that reality is the thing which, when you stop believing in it, refuses to go away. When we refuse to acknowledge reality, we put ourselves at risk and we cheapen ourselves.

How do you justify your tactic of paying your interviewees?

Many critics find it journalistic blasphemy. I am proud to practice the principle of fair exchange as I understand it. I disapprove of journalists who simply take a story from people and leave them with nothing.

Do you think money can bias a story?

Absolutely. So can anything else, including knowledge itself. It is the journalist’s job in all cases to expose the bias in his interviewes and in himself.

In a recent article in Bookforum, you critically quote Ariella Azoulay from her 2008 book The Civil Contract of Photography: “Studying a photograph that allows a reading of the injury inflicted on others becomes a civic skill, not an exercise in aesthetic appreciation.” You discuss the negotiation between the artistic/subjective use of photographs and their objective/archival importance. Do you consider the photos you take to illustrate your books works of art or photojournalism?

They are works of photojournalism. They are meant to say: “Look! Please do look! This is really how it was, or how I sincerely thought it was. The camera thought so, too.

Now, what do you think it means? What can or should we feel or do about this?

You have seen this picture, so now your opinion means something on this topic.”

But do you think that fiction can more truthfully, if not more accurately, portray history?

Nonfiction can sometimes go deeper (as in the case of Imperial), by eschewing the sometimes dangerous luxury of “readability.” Statistics are important; physics and chemistry and economics help us approach reality. on the other hand, fiction can say: “I imagine that the situation, and the person in that situation, was thus. I am going to imagine him as well as I can, and try to make him live. Then you may be able to feel the life of this bygone time as I did. of course, my imagination may be a spurious one. So take me with a grain of salt – just as you would a page of water statistics.”

The secret Chinese tunnels under Mexicali are the subject of a central chapter of Imperial. Can you talk about the relationship between physical and literary structures? Are these mysterious, subterranean structures below the city a spatial or urban cognate of the relationship between fiction and reality? That we build upon a ground that remains mysterious seems to be an idea operating in your work.

They certainly can be. I love the Jungian notion of the unconscious “shadow” which represents the other, the forbidden, the opposite, the evil, the erotic, the new. I made some use of it in Europe Central [2005]. Equally fascinating to me is the marxist notion of a material substructure which allows the cultural superstructure to operate. Do you remember H. G. Wells’s Time Machine [1895]? The subterranean Morlocks keep things running so that the hedonistic Eloi can enjoy the sun and make love. In exchange, the Morlocks get to eat the Eloi. Whatever lies beneath the surface may indeed devour what is above, especially if it goes unrecognized. Secrecy is power. This paradigm is what makes the best work of Poe, de Sade, and Lovecraft so haunting. Secrecy is also power in Orwell’s 1984 [1949], when Winston and Julia have their (so they believe) undiscovered love nest, where they can be soft and naked.

“My imagination may be a spurious one. So take me with a grain of salt – just as you would a page of water statistics.”

You’ve mentioned before how your biggest literary weakness has had to do with plotting. How are you improving this?

By living longer, which means ageing and changing, and seeing other people and places do the same. A baby has the same personality he will have as a grown man, and as a senile inmate in a nursing home, and yet certain aspects of that personality flower and then wilt; some fundamental idiosyncrasies are sharpened with age, or modified by others; and of course all things pass. We are all dying and in the process of losing everything. But there will be a different everything tomorrow. All this is obvious, but I am finally beginning to feel it and perceive it as well as merely think it. Isn’t that what plot is about? A lovely example is The Tale of Genji [an 11th-century Japanese literary work, often considered the world’s first novel], whose story continues at the same level of excellence after its protagonist’s death.

Many of your readers have bemoaned the fact that, despite their length, your books end suddenly. What sort of structure do you use, if any?

This is hard to answer. The “Seven Dreams” books need outlines, at least mental ones, since they are based on specific historical incidents. As for the others, I guess I would say that they end when their words strike in me some chord of fulfillment.

You often eschew conventional structures in which narratives have a beginning, middle, and end.

To me, they all have beginnings, middles, and ends.

Is there a difference between how you write nonfiction and how you write fiction?

When I say a work is nonfiction, then I try to make everything in it literally true. When a work is fiction, then I am free to blend truth and lies as I wish.

Editing, or lack thereof, is a source of much criticism about your work. Can you talk a bit about your self-editing process when you write?

I edit my books until they seem done. When I was a child, other children mostly did not like me (perhaps because I read more than they did). This was sad at the time, but it gave me strength, so that if reviewers think my books too long, if readers are offended or bored, if editors remind me of the increasing price of paper, well, I wish I could please them, because I do like to please people, but in the meantime, like Leonard Knight in Imperial, I will just keep doing things my way.

You’ve criticized the tendency in postmodern literature to focus too much on language games instead of trying to communicate in the most sincere way possible. However, you’ve used complicated structures, images, varying typefaces and other typically postmodern devices. How is your approach different?

I fondly (fatuously) imagine that my language games are means to an end, that my typefaces enhance the reader’s ability to visualize what I describe. I hope and believe that even ambiguity can be sincere.

In the past, you’ve mentioned that you don’t find postmodernism to be a very useful name for the context in which writers since the late 1970s onwards have found themselves. How do you see yourself within the context of your peers?

Of course, like each of us, I imagine myself to be a very special, unique sort of person, deserving of everything that I want to have, and therefore confounded by “unfairness.” And of course, like each of us, I resemble Tolstoy’s Ivan Ilyich, who is very proud of the decoration of his home, which resembles the homes of anyone of his class and time. So what is my context? I am me; I am you; I am nothing.

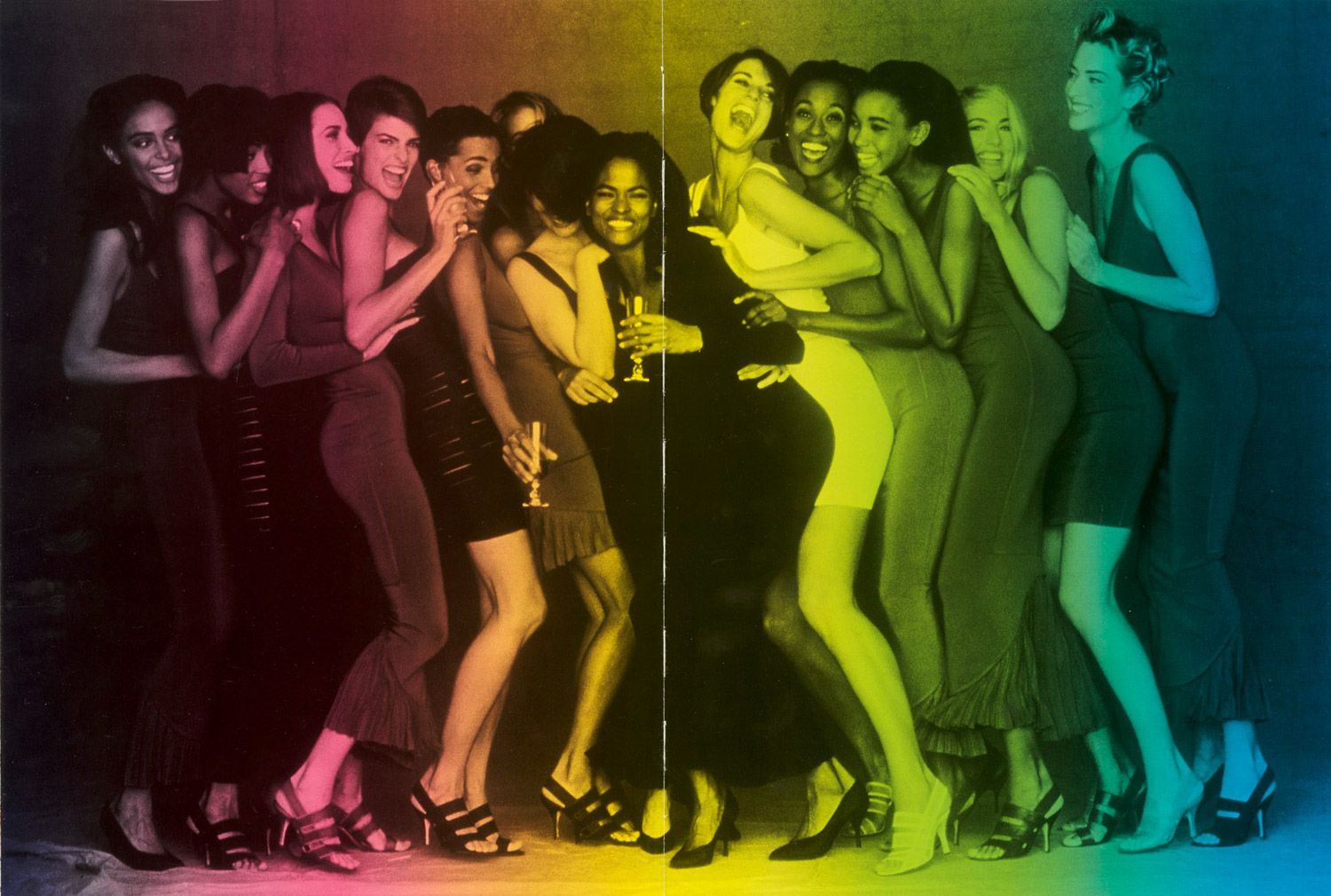

Prostitution is continually celebrated in your work as if for the transgressive way it lays bare the fundamental dynamics that drive culture: sex and money. In the Netherlands and Germany, prostitutes are given insurance packages – does this not completely dampen the transgressive or culturally revelatory power of prostitution?

I wish that all prostitutes could be given insurance. I hope for the day when prostitution will not be stigmatized, when there will be many types of licensed prostitutes: therapeutic, recreational, artistic (heterae-courtesans) – and when unlicensed ones won’t go to jail. like all human beings, I am fascinated by the transgressive, but that will always remain in one form or another, so I would rather see prostitutes safe from violence than be compelled by their very existence to provide it. (You want transgressive prostitution? go to a dominatrix.) In the meantime, I wish we could mature into a more realistic, wholesome attitude about our erotic needs. Even those who find sexuality an unpleasant topic ought to see that we cannot wish, say, defecation away, that we need toilets, sewers, etcetera; and the same line of reasoning goes for our other corporeal and psychological aspects. The Royal Family [2000] and Whores for Gloria [1991] derive much of their sadness from the fact that in my culture prostitution is considered sordid and even criminal.

Unlike America, could the Dutch or German state, then, be the equivalent of the Queen of the Whores, the caretaking character you’ve developed in The Royal Family?

Why not? I would rather drink my social contract from the breast (or vulva) of an affectionate female than receive my sustenance from an indifferent bureaucrat or worse. On this topic, why has the German state so often been termed “paternalistic” while germany’s not so distant neighbors speak of mother Russia? How happy I would be to live in Sweetheart America!

American mythology is founded on being able to change who you are – perhaps one of the strongest cultural incarnations of an Ovidian ethos. Do you think that we’ve lost that capacity?

“Like each of us, I resemble Tolstoy’s Ivan Ilyich, who is very proud of the decoration of his home, which resembles the homes of anyone of his class and time. So what is my context? I am me; I am you; I am nothing.”

The overt emergence of transgender people is an exciting, indeed astounding, hallmark of American ovidianism. I love it. And I sincerely believe that we are making measurable progress in transforming ourselves away from racism. The election of a black President, the increasing freedom of interracial couples to go where they please without nasty consequences – these are very wonderful things. But it may be that, in general, the transformations encouraged by American individualism take place more in the symbolic, mental, cybernetic realms than in “physical reality.” Social Security numbers, the Patriot Act, concern about legal liability, the decay of the cash economy, all these things make it more difficult to check into a hotel room with a secret lover. And changing homesteads and professions, how big a deal is that when every state has similar fast-food chains, and when bank tellers, pharmacists, construction contractors, and so many others are for better and for worse less autonomous each year.

In Europe Central, you write that “one of life’s best pleasures is reading a book of perfect beauty; more pleasurable still is rereading that book; most pleasurable of all is lending it to the person one loves.” Do you distinguish between reading for pleasure and reading for research?

Reading is always pleasure for me, but there are many different kinds of pleasures. Sometimes the pleasure comes from teasing out a pattern (even a horrible or frightening one, in which case the pleasure is submerged in ghastliness) or discovering a provisional answer. Sometimes it comes from the utter joy of the beautiful sentence, image, story, or world. Sometimes it comes from the unexpected. Sometimes it comes from increasing my understanding of the world, as when I dip into my old college ecology textbook.

Is there a larger project behind mapping the world through fiction? Do you desire to chart your whole world through writing?

For my answer, I refer to you the prospectus for my “Seven Dreams” series. I wrote this about 20 years ago but it still gives a fair idea of what I am trying to do with landscapes.

Credits

- Interview: CARSON CHAN & MATTHEW EVANS