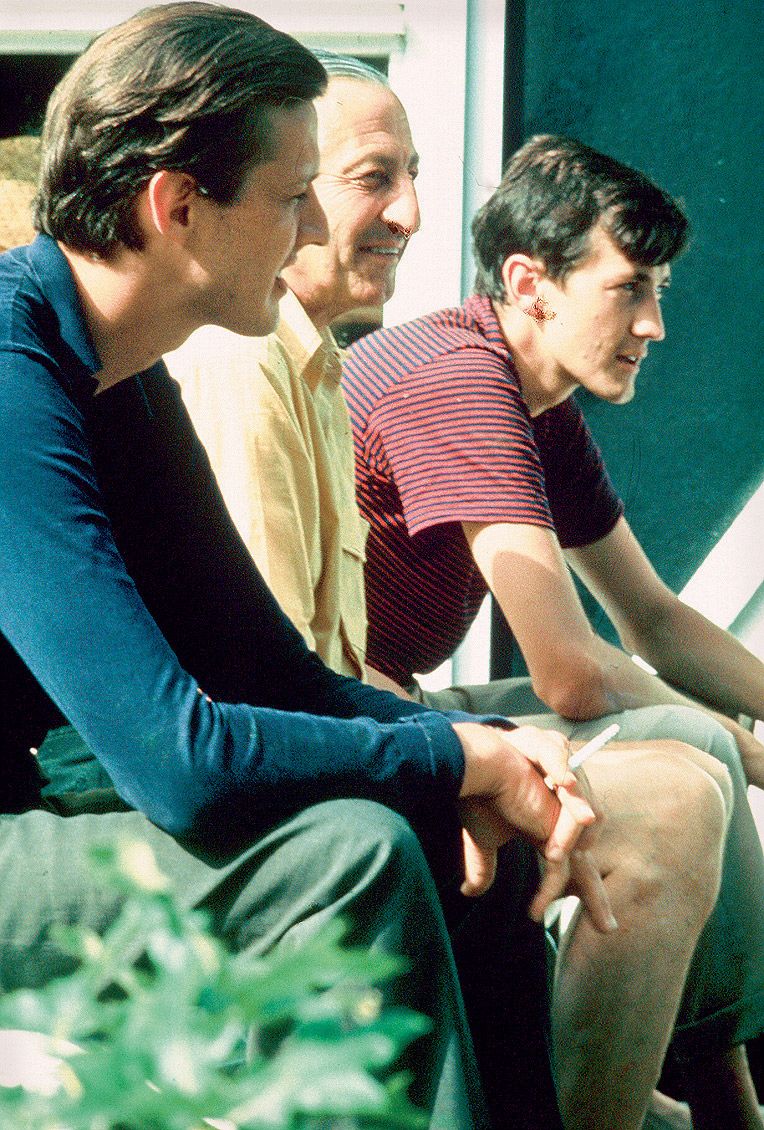

ALEXANDER KLUGE: Writing Attitude

|JOACHIM BESSING

“For a single story, three lines are enough. But for the context, one needs encyclopedic formats.”

JOACHIM BESSING: Your books sometimes run over 1,000 pages. Are books that thick still bought and read?

ALEXANDER KLUGE: First, no book in this world is alone. Books are trustworthy precisely because they’ve been corresponding with each other for more than 2,000 years. So it really doesn’t matter if a particular period takes to thick books or not.

Could you write more succinctly?

Books are a bit like rafts; I wouldn’t even say steamboats or ships. But they’re on this huge ocean of language, of emotion, of communication – it doesn’t matter what form of expression they take – but out there, books are something like tree trunks, bound together. And they can and should have a certain surface; and it takes shape according to the object it deals with. My new book, The Hole the Devil Leaves, has stories from the last three years. After 1989, for a long time I didn’t think it was possible that we would have plunged into a storm zone of time that we’re experiencing now in 2003 – on the planet. But writing doesn’t come from the outside. It comes from within. How does one answer, as a bat? Yes? What does one call out for a sonic depth finder? It becomes more intense in such incredible times. You’ll have noticed that the stories by themselves are very short. The authors I find trustworthy – whether it’s Heiner Müller, or Ovid, or Heinrich von Kleist, Michel de Montaigne – all of them write short texts, and compromise. So in this way, it’s not unusual for me to write succinctly. Even so, there’s no connection if you don’t allow these shorts to add up to chapters that, in the end, amount to 960 pages. That’s not what I’m aiming for, you understand? I’m glad when I can get something down on fourteen pages. Or 300 pages. It’s not subject to the worthiness of the author. Instead, the texts come about, too, to a certain extent, blind.

What does that mean, blind?

Blind means, and I don’t want to come off artistically naive, but from the lead of a pencil, a story takes form. And whichever way it turns I can’t determine beforehand. I’m not in charge of the story.

You don’t plan things out beforehand?

No. But I know my interests. I know what moves me. And I’m absolutely involved in the study of the object. And then a relationship evolves between this interest in me and the object, a relationship that regulates itself.

“Assume I’ve got an anti-academic or anti-literary attitude towards literature.”

What inspires you to write a story?

There’s either a note; or, on the other hand, a feeling. You can carry it within you for years sometimes. Usually it’s a scene, an image. It’s short, in any case. And a story builds up around that, sometimes several around the same seed. But no reader would be able to make out this shared seed later on.

When you write, what point of view do you take?

There’s a sentence from Georg Büchner that says, “I’ve always wanted to see what my head looks like from above.” That’s an interesting metaphor. Writing literary texts, you look – if you’re going about it correctly – down to yourself, to your head from above. Then you no longer have a relationship with yourself. At the most, you have trust in yourself that a text will emerge from this and that you still have the sovereignty and the strength to throw it away if it amounts to nothing. Within us, as humans, there are libidinous kernels that come from an experience but are never the experience itself. And never the mirror itself. Always just an echo. And they’re like monads. On their own, they’re blind. And they have a very powerful will. They’re the ones that decide what stories are to be told. It wouldn’t be any different with a conversation in a bar. Professional poets, they concentrate on that a bit more. They’re used to making books out of all that. That’s the actual difference between what authors do and what everyone else does.

So you’re saying everyone can write. Everything people report is worth reporting.

First, there is no censor. No ultimate judge outside of the academies and that sort of thing, which I think are rather silly anyway. No one who can say that a story is worthless. I look at two people in a café one afternoon and they’re drinking quite a bit of red wine, which surprises me a bit, and the conversation grows more and more lively, and then they begin to fall asleep, and then they get down to business and this business, I would suspect, is being influenced by the wine. A simple observation. Anyone could make such an observation!

That’s true. But who’s going to read all these observations?

The writer is able to edit such blind observations. Meaning I express myself far more concisely than a normal person telling a story. Or someone writing on the Internet, contributing to that whole flood, the element of communication. I can build containers that float. I have a whole variety of storytelling abilities that I haven’t invented myself, but are viewed as reliable tools by trustworthy authors. The awareness of these is professional. But only professional in the way that you would turn a screw. They don’t use them consciously – in the same way that evolution has made it possible for a millipede to move its legs, but not to think about moving them.

So there are literary techniques one can learn? And at the same time, there are also geniuses?

The woman – Anna Wilde was her name – who cleaned the doctor’s offices of my father in Halberstadt was a gifted storyteller. She could tell stories in ways I could never write them. She was also able to be concise. And she can, when she’s, let’s say afraid, tell a story differently than when she’s relaxed. The stories she tells are completely dependent on the person she’s telling them to. That’s what makes her a natural poet. Only, there’s no one to record it all.

Still, there are, evidently, certain techniques one can master?

That’s right. But assume I’ve got an anti-academic or anti-literary attitude towards literature. I don’t think there’s such a thing as literature in and of itself. Instead, there’s a convention that makes it possible to print texts by Marcel Proust, Franz Kafka, Robert Musil, and distribute them in different ways than natural texts. Because there’s no one present to record them. But I couldn’t render a fundamental difference in the fairy tales of the Brothers Grimm, or in the raw material at the core of the Grimms’ tales because it wouldn’t be correctly recorded. And if you were to take up, in the case of Georg Büchner, the foundation of Lenz, the protocol of the statement of Oberlin, the preacher. A protocol is literature of the highest quality. And along comes Büchner who not only develops a higher tone, but a more precise tone, one richer in experience. So that experiences arise that are not in the Oberlin report. And the ability to not suppress or leave out anything that’s in the report, but at the same time, introduce, so to say, new, higher tones, rich in experience – that’s the ability of Büchner the writer. But that’s not arbitrarily poetic, that is, he’s not picking up a lyre to start singing. It’s not poetic in the conventional sense. Instead, he’s concentrated the elements outside the authentic material. And that’s what rattles Alban Berg. And among Büchner’s work is also Woyzeck, one of Alban Berg’s operas. Just as Bernd Alois Zimmerman’s opera Die Soldaten (The Soldiers) is based on Lenz.

But can the taking down of a protocol not be simply a style that has little or nothing to do with the actual event being recorded?

That can very well happen. In very rare cases, it can also be literature of very high quality. And I can’t really get across to you the difference between facts and fakes. Both are literary methods. You couldn’t say that there is an authentic report at the base of the Münchhausen stories. I think that the artistic, the unique, or the trustworthy quality has to do with whether it moves back and forth between two impossible points like a tight-rope walker. And doesn’t fall, neither to the right, nor to the left. The extreme tension in particular, the extreme opposition, the line of resistance between fiction and non-fiction is the primary challenge. The greater the dare, the better the text.

What drives you to write?

We’ve been talking about kernels. These kernels are obsessions. You’ve got to express them. They drive you.

“What interests me again and again is how to find a non-moralizing method. That is, not based on morality alone, against a moralizing faith in fate. I’m very moralistic, but I don’t believe that morality brings great numbers of people together in unity.”

That’s it?

That’s the initial raw material of motivation for writing something: a drive.

But you’d also want the product, the book, to be read?

That can’t be a part of it at that moment of pursuing that drive.

Do you not have that in mind after the umpteenth publication?

No. I don’t have to publish, either, you see? That would be a question to raise much later. The way one acts when driven shapes times such as, for example, when you say, “I don’t care if my grandmother’s dying, I’ve got to write.”

Do you write what you’d like to read yourself?

That can be. But it’s not something you think about at the moment you’re writing. I’m interested in stars, for example. And so, of course, I’m always looking to see if I can’t work that in a bit.

Can’t you just decide to?

You definitely can’t make plans. They burn up. You must know what a weaving arc is?

For welding?

Yes, for welding. You ignite between two opposing raw materials. One of them is the inner image. From a very specific single scene. A mound of grass, say, next to a circus. That’s not particularly Earth shaking. But I’ve seen it. And what came to me then is that it’s enough ground for a head of someone who’s fallen to lie on. So, that doesn’t have anything to do with the circus directly and it isn’t logical. And now, this story goes searching as long as it takes – if necessary, even 40 years – for an opposite, an object out of which one can develop a story. Or I’ve seen a man without a head at the circus. Just to stick with the circus.

What do you mean, a man without a head?

Well, that’s a figure. He’s got a cloth covering his head over a frame, and then, he carries a head under his arm. He comes in and scares the audience; an ancient circus illusion. But when I was a child, he really moved me. Because I didn’t know that he didn’t … I thought he was beheaded.

There’s an ignition between a pair of images?

This image that’s scared people; I can’t, as a writer, describe it. If I set out to, first, it’s a plan, and the words won’t come and I struggle, and in the end I discover that it really isn’t important what I thought as a child. And second, I’m not this child anymore. Which means that this text is probably doomed. But if I pick up a story that I discover and describe as a document, then the power of the impression from back then makes it possible to tell this story concisely, to give it a form. Meaning that this personal experience, this subjective side takes on almost a completely new form. And transforms the document into a story.

Is style important to you?

Well, form is. You can forget about style. Style would be something that I’d find alone. I have no ideals. What I do when I write is concentrate – sometimes on a single unit. And I try to express it as intensively as I can. Afterwards, I forget it and turn to another intensity. And the difference is that it’s my expression.

Are you self-critical?

Not at the moment I’m writing. It writes itself. Later, I can go over it in peace. Whether it’s, for example, a story that fits in this chapter or another. I never write stories in complete isolation, but – you know a full house in poker? – the epitome for me would be for seven or fourteen stories to collectively represent one expression. What matters little in one story would be the core of another. But in that one, there’s another unimportant matter that would be the center of a third. All of them, taken together, have a shared subtext. And it can be aborted. Then comes another one. That’s one form of writing I favor.

Where does this tendency to fragment come from?

It’s not actually fragmentary. The pieces fit together.

Let’s say, the breaking down into individual texts.

For one thing, that has to do with my interest in multiplicity. That I’m not satisfied with one story. Like a shadow, like an echo, I want to draw out the story behind this story, and the third and the fourth and the fifth. At the same time, there’s actually another story going on. And it doesn’t want to be expressed at all. It won’t appear.

Do you still have faith in the novel as a form?

Yes and no. I consider what I’m doing the modern form of the novel.

But there is also the counter movement that swears by the bourgeois novel, the stringent story.

That’s possible as well. And it’s something I very much enjoy reading. The novel that’s shaken me most is Anna Karenina. You can’t say anything other than that it’s a novel. And I could make you at least ten reworkings that would be relatively short. One of them would be the story of Anna Karenina, how her son saves her. That’s how it appeared in my Chronik der Gefühle. You see, the moralistic perspective that motivated Tolstoy to write this great novel is my main concern. What interests me again and again is how to find a non-moralizing method. That is, not based on morality alone, against a moralizing faith in fate. I’m very moralistic, but I don’t believe that morality brings great numbers of people together in unity. How can I tell a happy story without betraying the bitterness of objective circumstances; to an extent, to defuse the aura of fate bound up in family novels; five generations of a success story. And I would be more concise because I can determine the pattern for a contemporary reader – he has, after all, already read a few novels.

Is that a technical progression?

Let’s say it’s a progression in time that allows a storyteller to be more concise. You can refer to something the reader is already aware of. And so, you can now build up constellations. I find a constellation more important than the more usual novelistic narrative. The novel needs an anti-novel. Like the earth has a moon. Like the way everything influences everything else, which makes it rich. Let’s say my idol is a spinstress in Byzantium. Her name is Arachne and she spun silk, so she was a manual laborer. She could weave pictures into silken vestments. They were miniaturized scenes, little novels. And because they were so good and so famous, Arachne competed against Athena and won. Which is why the gods turned her into a spider. To weave nets from then on. That’s an author. She makes connections. And these connections can take the form of a bourgeois novel – Thomas Mann could do that. But as they tell their stories, they have to shut out an awful lot.

Or bend?

They have to bend things now and then or cheat. But that’s not an accusation. That’s also a question of literary ability, whether that can be avoided. You can write novels today. The idea that the great bourgeois novel has seen its day is an exaggerated thesis. Take, for example, the earliest novel I know, Die Prinzessin von Cleve (The Princess of Cleve). It’s about our questions:

How do I structure my life? Which of my feelings are my own? What can contracts with partners be based on? How much can I trust my mother? Can I trust someone I love? Even if there’s a danger that he could hurt me more than anyone else? That’s why the princess in the novel becomes a nun at first. So I say, “Today, someone would have to write a commentary 2,000 pages long.” Like Abälard of Aristoteles receiving the preamble from a Persian scholar – seventeen lines, and they were smudged. Abälard writes a commentary on them, twenty volumes worth. So we come to the chain of categories; we need commentary. Primary text. Connections. Context. Then literature is able to correspond with the Internet, which has a huge context, albeit one that’s rather confusing. A single novel can only create such context if it makes full use of James Joyce’s methods. And at some point, that leads to the inability to recognize the main story at all.

“Within us, as humans, there are libidinous kernels that come from an experience but are never the experience itself. And never the mirror itself. Always just an echo. And they’re like monads. On their own, they’re blind.”

Is it a form of sportsmanship, all these pages? The iron will in the face of the huge work that remains to be done?

For a single story, three lines are enough. But for the context, one needs encyclopedic formats.

Who’s able to create them?

That’s not a serious question for the one who writes the three lines. As you dive into a single story, you can’t be thinking about whether it will lead to a long or a short work. Those are two completely different containers. The first is about making an experience as concise as possible and as authentic as possible for a concrete reader that you imagine – Adorno, for example, or Montaigne, or Ovid, or some colleague; or my mother, my sister – you see? How can I do that most directly? A completely different container from when, later – in the meantime, you’ve already told quite a lot in this way – you place it in the context of others in series, montages, or chapters.

While writing the three lines, can one tell where it will lead?

Maybe; maybe not. But when you’ve reached a certain age, and have done a few things, then you have the experience, the trust. It’ll all add up. And sometimes, you do know that, as you reach the end of a story, you’d like to write the parallel story as well. And I do that on the other side of the page. I still write everything by hand.

Is your handwriting large or small?

I’ve got a pretty average handwriting.

Are there times when you just can’t write anymore?

That definitely happens. And you shouldn’t write on then, either.

Instead?

Then the story’s come to an end. Could be that it’s the right thing to do to stop there.

And if you're in the middle of some ongoing event?

Then you have to sleep. Wait. See if it comes back. If nothing comes back, then you have to scratch the story. In general, you can’t have a planned economy when it comes to writing.

Is it a consolation for you that you're not only a writer but also a television producer, film director, and interviewer?

If, for example, it happens the other way around, where I can’t tell a story, or I run into a block. I can tell when I can no longer regulate what I consider to be the real kernel of the story. It’s not right. That would not only be a block; that would be the end of the story. But then I’ve got an appointment with my film team. And I interview a scientist. Then I can enjoy conducting this interview since I’ve got my other interests besides writing.

Is the range of your interests one reason for the range of your works?

In order to describe a social climate, you need large constellations. That’s why there are 20,000 pages. Because a context of this size simply has this dimension. If you don’t want to be superficial, you have to pour it into some form, and you can help yourself by making full use of the ability to tell stories concisely. But that alone won’t help you. At the same time, you need a feeling for the bending of dialectic relations. To describe them, that’s our work as writers. It’s been very interesting for me to learn that the idea of Noah’s Ark is based on a false translation. It’s actually a box of holy writings. Sacred books were saved from the flood on Mount Ararat.

And the animals?

They weren’t there because – thanks to the powers of translation – it was mistaken for a ship. That is, a box for animals and people. And that was what was written down, what then became of the wandering tale of Noah’s Ark. But it’s actually the story of the ability of writings to survive. And to have long roots. Over time. Into the future. Whole peoples could survive an exodus if they had writing. That’s what the story of Noah’s Ark is about. If you believe that that’s the function of books, then you can set your stories up on that. And that’s the only point at which I can say that the power of the will and planning and self-assurance and, if you will, self-confidence as well can serve as a motive. I consider other authors trustworthy when they work on this spider’s web of narrative. But that’s not anything you could write a single story with. But you can say, “Yes, I believe that what I’m doing with my life is to an extent meaningful.” It doesn’t matter if anyone else thinks the books are too thick, to return to your original question.

Credits

- Interview: JOACHIM BESSING