MICHAEL POLLAN Changes His Mind

|PHILIPP OEHMKE

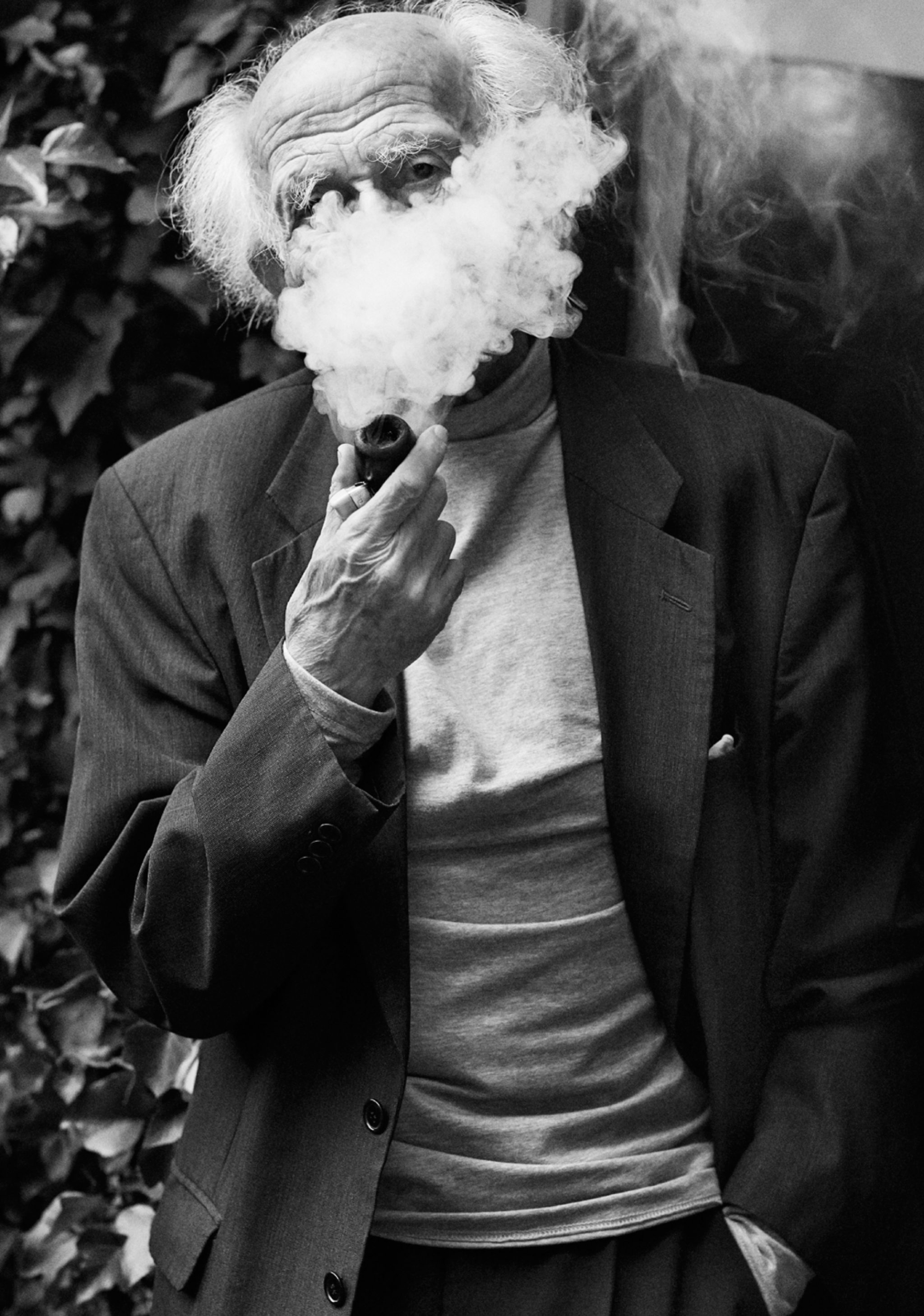

Journalist Michael Pollan writes about “the places where nature and culture intersect,” and made a name for himself in the last decade and a half with nonfiction books about what we eat. His 2006 The Omnivore’s Dilemma: A Natural History of Four Meals looked at models of food production and consumption in the 21st century, criticizing industrialized agribusiness. His In Defense of Food: An Eater’s Manifesto (2008) promoted a simple (and much-cited) nutritional doctrine: “Eat food. Not too much. Mostly plants.” In his latest book, however, Pollan turns to a different – and, for him, much less familiar – category of consumption: psychedelic drugs.

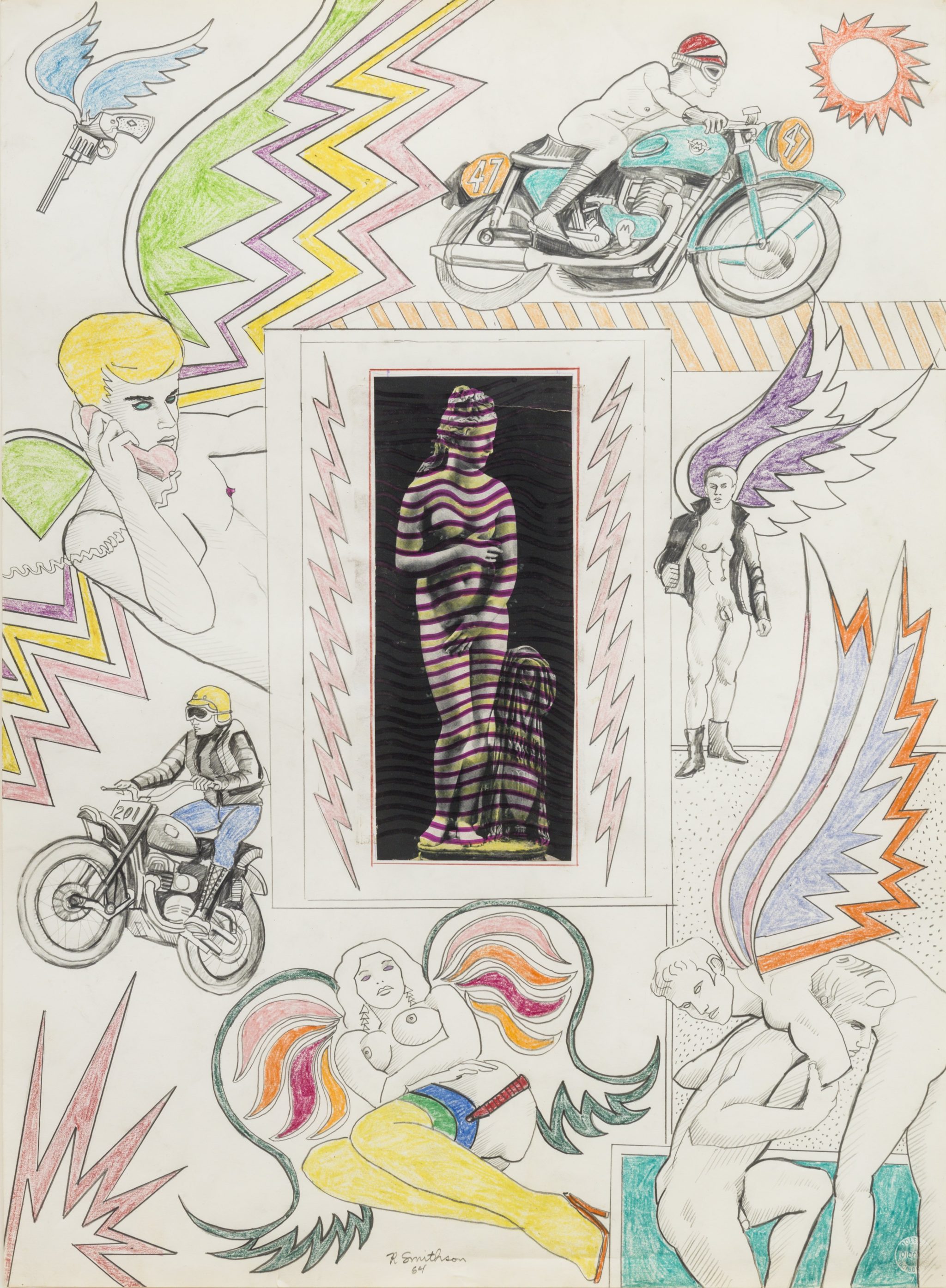

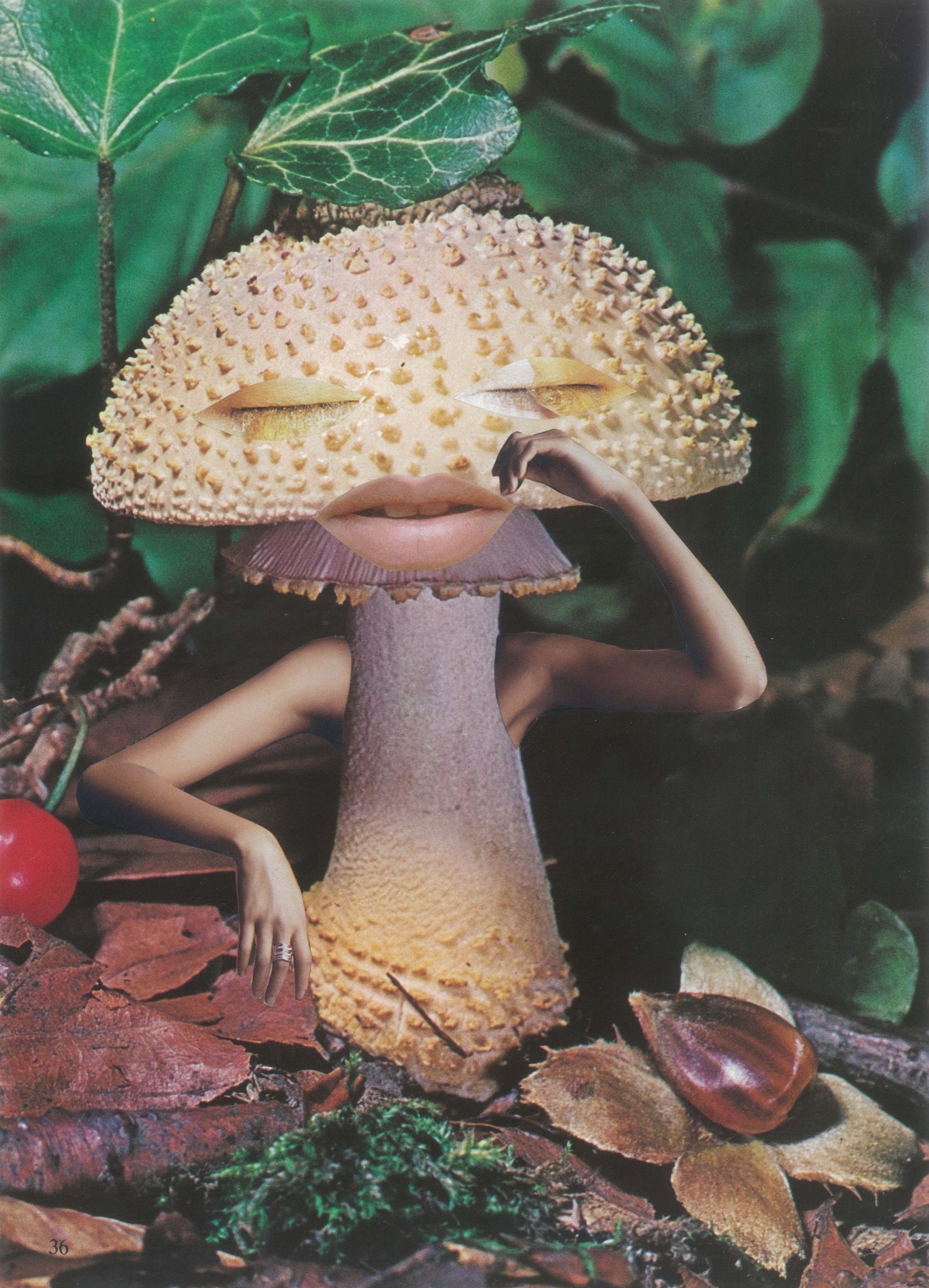

Coined by the psychiatrist Humphry Osmond in a letter to Aldous Huxley, the term “psychedelic” is built from the Greek words for “mind” and “to clarify.” These origins correspond to one effect of hallucinogenic substances – and to a central argument in Pollan’s recent How to Change Your Mind: What the New Science of Psychedelics Teaches Us About Consciousness, Dying, Addiction, Depression, and Transcendence (2018). The work originated with its author’s attraction to new research on the therapeutic benefits of LSD and psilocybin – the active ingredient in “magic” mushrooms – in individuals suffering from depression, addiction, and anxiety. Pollan found himself so compelled by these substances’ apparent capacity to improve lives that he decided to try them himself. The result is a book that charts the history of psychedelics – the first golden age of research in the 1950s, the phantasmagoria of the 1960s, and the ban on LSD and similar substances by 1970 – while recording Pollan’s own experiences in six personal “trips,” which included smoking the crystallized venom of a Sonoran Desert toad.

Countercultural icons Ken Kesey and Timothy Leary saw a radical potential to transform the psyche, and society with it, using psychedelic drugs. Unfortunately, governments did too, slamming the doors of perception shut. In recent years, however, interest in these substances has surged again: not only has scientific research resumed, but today tourists play shaman on ayahuasca retreats in South America while tech workers in Silicon Valley microdose to stimulate creative productivity. Times have certainly changed since Leary envisioned a hallucinogenic social revolution: “The kids who take LSD … aren’t going to join your corporation.”

Drawing on interviews with neuroscientists, ethnobotanists, and seasoned psychonauts, Pollan confronts the tricky task of writing about what drugs feel like (without sounding cringe). His conclusion from this expanded “trip” was that psychedelics may have much broader benefits than the alleviation of mental disorder. “The mind is vaster,” Pollan writes, “and the world ever so much more alive, than I knew when I began.” LSD really is an acid, and the first thing it dissolves is your self.

PHILIPP OEHMKE: When you first took psychedelics you were around the age of 60. In your book, you say that it felt as if your ego dissolved. What could that possibly mean: the “dissolution of the ego”?

MICHAEL POLLAN: It’s something I had read about beforehand. When people I interviewed for the book would describe mystical experiences on LSD or psilocybin, they often claimed to have seen their sense of self completely dissolving. But, of course, that was unimaginable. What’s that supposed to mean? Your sense of self dissolving – aren’t you dead then? Then it happened to me, too, on one of my guided trips on psilocybin.

Psilocybin – that’s what we call magic mushrooms?

Correct. My guide had given me one to eat.

A guide? Like a mountain guide?

Yes, I took six or seven guided trips for the book. You need a guide and I had actually been searching for quite a while for someone who would take care of me on my journeys. The woman who helped me is around 60 and did her training with prominent people in the scene who experimented with psychedelics when they were still legal, before 1970. In the book I call her Mary.

You cannot reveal her real name because what she’s doing is actually illegal.

Yes. We sat in her second-story loft in a small town somewhere on the Eastern Seaboard. I suggested that we make a tea from the mushroom but she wanted me to eat it. It was big and it tasted like cardboard. They don’t taste good. Mary said I could alternate bites with dark chocolate. That helped.

And then?

Half an hour later I started feeling a little woozy. I lay down on a mattress and put a sleep mask on. Mary had given me some idea of what to expect, almost like a flight attendant before takeoff. She said: “Don’t fight it. And if you see a monster, step right up to it and ask what it has to teach you.”

What happened after you put the sleep mask on?

Most of the trip was pretty unpleasant. I found myself in a cold digitized landscape at nighttime, very much like a computer game. Soon I was getting kind of claustrophobic. I wanted to get out of there, so I asked Mary for a booster [dose] and also for different music. Instead of the New Age stuff she had put on – the kind of music that you would hear in a luxury spa – I wanted Bach’s “Cello Suite No. 2,” a bottomlessly sad piece. Then I looked out and saw myself bursting into a cloud of little pieces of paper, like those yellow Post-it notes. I saw all of this from a perspective I had never had before: it was clearly me watching my own self-dissolution. But the perspective I was seeing from was so untroubled. It felt neutral. It wasn’t alarming at all.

“I was liquefied and spread over the landscape like butter or paint.”

It didn’t bother you that you were dissolving?

Not at all. That’s why psychedelics have been used with cancer patients. They can help terminally ill people acquire an indifference toward their own destiny. Meanwhile, I was fully conscious. I was a cloud of scraps of paper. And I didn’t feel the desire to piece these scraps back together again.

How did you know these scraps of paper were actually you?

It was just totally clear. And then when I looked out again I wasn’t even that. I was liquefied and spread over the landscape like butter or paint.

That all sounds very strange. It’s hard to imagine.

I know.

If you were a heap of paper scraps, who observed all of this? If the duality between subject and object collapses, then…

Exactly – it changes everything. It makes everything that defines our western thinking null and void. We assume that we are identical to ourselves. But Buddhists, for instance, have been telling us for a long time that our perception of the individual is an illusion. And that there are other perspectives that can be acquired.

So what do we do with that?

First, we could try to understand what happens in the brain neuroscientifically. What comes closest to a material correspondent to the ego, or autobiographical self, is the default mode network in the brain – the brain’s “normal setting.” It filters and controls what appears to us: internally, our memories and feelings, and externally, our sensory perception. Like a chief of staff, it determines what’s allowed to come in, and who is allowed to speak to whom in the brain. It prevents excessive communication so that there isn’t a clutter of voices in the head. Most of the brain regions aren’t allowed to directly communicate with one another. So normally the default mode network is running the show. But when it goes quiet under the influence of psychedelic drugs, all these networks start talking directly to one another. That, for example, probably explains things like synesthesia. It means that your visual cortex is talking to your auditory cortex without going through the chief of staff. That explains how we hear visuals or see music, just as I did on psilocybin. In short, the default mode network allows us to focus or to block out our perceptions, memories, and sensations when we need to.

That means we wouldn’t be able to conduct this interview if this consciousness filter wasn’t turned on? Because we both would be overcome by unpleasant childhood memories, or, for that matter, by this spectacular view from your living room over the San Francisco Bay?

That’s right. Isn’t that a wonderful achievement? It’s also sometimes called the “spotlight consciousness.” It’s only fully developed in adults. The child psychologist Alison Gopnik has conducted studies that show that young children still lack a developed default mode network. Their consciousness resembles that of an adult on LSD – the so-called “lantern consciousness,” which illuminates everything kind of equally. In this state of consciousness, it is difficult to concentrate, but one is good at thinking out of the box. In comparison, the brain of an adult in its default mode is a prediction machine. It tries to immediately classify incoming information into familiar models of reality, and to take in only as much information as is absolutely necessary. It’s a “controlled hallucination,” as one of the neuroscientists I spoke to put it.

But psychedelics can turn the default mode network off ?

They push it into the background at least. The brain is temporarily rewired. In the default mode network you can see just a few large highways between the different main regions in the brain. But when the network is pushed back, every region is suddenly communicating with all the others. It’s like the teacher has left the classroom.

What can we take away from that?

Well, even a temporary connection in the mind is a learning. You’re forming new paths that you can perhaps then exercise. And that maybe allows you to break bad habits.

Is that how it went for you?

Yes. Furthermore, psychedelics are a useful tool to learn about something we have never understood very well: human consciousness. The psychiatrist Stanislav Grof, one of the most important researchers on alternate states of consciousness, put it like this: “What the microscope is for biology or the telescope is for astronomy, LSD is for researching consciousness.” That’s an audacious claim. But the more I talked to scientists and researchers, the more I thought he was onto something. One way to understand any system is by disturbing it.

“Psychedelics are an attack on the ego. But the ego is very clever. It has control over our rational institutions and it is very persuasive.”

If our consciousness protects us from things that might overwhelm us, or that we are not prepared for, maybe we shouldn’t mess around with it.

Hence the sleepless nights before each of the experiments I conducted on myself. I was scared and a very reluctant psychonaut.

What were you scared of ? You probably knew that bad trips or psychoses are quite rare under controlled conditions.

I was worried that I would discover something really disturbing about myself. That maybe I was not as sane as I thought I was. The thought of mental illness was scary.

Did you have any reason to believe that there were any dark secrets to uncover?

Not really, although I had a very difficult period in my teenage years, when I wasn’t very stable. Now my life is actually pretty good. I don’t want to lose it. So during those sleepless nights, my mind played pingpong with itself. Part of me was saying: “You have to do this so that you can write the book. Otherwise what kind of journalist are you?” And the other part was going: “Are you crazy? Why do you want to mess around with your mind? You’re 60 and have heart problems. You could have a heart attack. And this illegal guide will definitely not call an ambulance.” Today I know that that was my ego trying to head this off. It felt its dominance was being threatened. Psychedelics are an attack on the ego. But the ego is very clever. It has control over our rational institutions and it is very persuasive.

You are speaking about your ego as if it wasn’t you.

That’s right. But after psilocybin, you are less likely to assume that you are nothing without it. That makes you calmer. You become more likely to recognize the ego as just one actor in the drama of your mind. And not the only one. You needn’t always listen to it. That’s also something that psychotherapy does: it teaches us to acquire some distance from our egos. The difference is, my psilocybin session happened in one afternoon. It didn’t take ten years like psychotherapy.

These substances have always existed in nature. How did we come up with the idea that there are things that we could take to temporarily alter our minds?

Humans have a universal desire to alter consciousness. Psychedelics have probably contributed to cultural evolution in important ways. Many inventors claim that these substances helped them come up with new ideas: Steve Jobs, Kary Mullis, who invented the polymerase chain reaction, Francis Crick. Some claim that Crick glimpsed the structure of DNA on an LSD trip.

So without LSD, no DNA and no computers?

You could even go further than that. We know that ancient Greeks underwent an annual psychedelic trip to gain insight. There are many scholars who suspect that psychedelic experiences may have been at the root of the religious impulse. Where else would you get the idea that there’s an afterlife? Or that there’s another hidden reality?

If you claim your trip was a religious experience, you are more likely to be believed.

Or suppressed. When the Spanish colonists came to Mexico, they found that the native population was using mushrooms as part of their religious observance. The problem for the Christians was that this was a more effective sacrament because you actually did see god. You met god on these mushrooms. The Spanish, who believed in god but had never seen him, felt threatened and killed what they called a “cult.” This mushroom culture went underground and continued to exist in Mexico for almost 500 years without anyone in the west being aware of it – until 1955, when the New York banker R. Gordon Wasson took part in a mushroom ceremony in Mexico and then told the world about it in Life magazine.

And was immediately considered to be insane.

It quickly became clear that the experiences one has on psilocybin are difficult, if not impossible, to express. We have no language for these experiences, possibly because we aren’t even capable of think ing about them – the dissolution of the ego, the dissolution of the duality of subject and object, and so on. The passages in the book where I report on my experiences were the most difficult to write. You either sound crazy or naive. I felt a universal love I never knew before that seemed to be the solution for everything. But it was hard to say afterwards that “I have it! The answer is love!”

All you need is love.

That’s something we put on Hallmark cards. The line between the profound and the banal is very fine. I wrote about a well-known TV journalist who was suffering from untreatable cancer and who, before his death, took part in a psilocybin study at New York University to get over his fear of dying. During one of his trips, he suddenly said, “Oh man, it’s all so easy. Love is the key. I don’t understand anymore why we have wars at all!”

Did the psilocybin help him with his fear of dying?

That’s how the researchers at the university saw it. He became a happy person before he died. The results are considered remarkable in psychotherapeutic circles.

How do you react when people call you crazy?

That doesn’t affect me. I don’t know anybody who has dealt with this subject matter even a little who would say it was crazy. Maybe people who, say, only know the pop cultural or hippie version of the history of psychedelics. I was actually surprised how receptive the psychiatric community was. In psychiatric circles, a spirit of optimism now dominates regard ing the use of psilocybin and LSD. And authorities in Europe and in the USA are now more open to further studies.

In the 60s, everyone was talking about LSD. It was the subject of hundreds of songs and other artworks. Psychedelics seemed to have arrived in mainstream culture.

It’s an interesting misconception that the hype around LSD or magic mushrooms began in the 60s with Timothy Leary and the hippies. In fact, that was the end, the last chapter. There had been a very rich history of research before Leary and the hippie move ment came along.

When did it start?

In the seemingly conservative 50s, of all times. A whole community of psychiatrists both in Europe and the United States had been given access to LSD by Sandoz, the Swiss pharmaceutical company where Albert Hofmann had discovered the formula in 1943. They owned the patent and knew that they were sitting on a very powerful psychoactive substance, but they didn’t know what it was good for. So they let researchers who were interested in it experiment.

“People’s tolerance for authoritarianism goes down. This could be the drug we need right now.”

Meanwhile, it’s become almost impossible to talk about LSD as a prescription drug. Today LSD is an illegal substance carrying a lot of countercultural baggage.

Yet it was legal until 1966, a substance that was tested in clinical lab environments with fascinating results. At first they thought LSD was a good way to mimic schizophrenia, giving therapists access to their patients’ minds by taking the substance themselves. At the time it was normal for researchers to use the drugs. Then LSD was used to treat alcoholism. The hypothesis was that a bad trip mimics the delirium tremens alcoholics experience. They would put the alcoholic through a simulated hell, hoping it would cause a great enough shock to stop the alcoholic from drinking. They soon discovered that bad trips were actually rare and the whole thing was much too pleasant. It became clear that this substance was somehow capable of bringing the subconscious to the fore. In psychotherapy, it could give people access to their subconscious thoughts and repressed memories. Between 1950 and 1965, there were 40,000 research subjects, 6 international conferences, and 2,000 peer-reviewed studies published. Psychedelics were at the center of psychiatric research.

And then what happened?

Then the 60s came. The drug escaped the laboratory and was embraced by the counterculture. Here in the San Francisco area, the writer Ken Kesey volunteered to be a subject in a CIA experiment for about 50 or 100 dollars. The CIA had also heard of this crazy stuff and wanted to see whether it could be weaponized.

Dissolving the egos of the opposing forces – that could be a pretty good weapon.

Yeah, but they gave it to the wrong guy. After his first trips, it became clear to him that this substance was not some weapon of war but a fantastic tool for cultural change. You just had to give it to as many people as possible. So Kesey started his Acid Tests – mass events on LSD. At the same time, on the East Coast, you had Timothy Leary, a psychology professor who had a very good reputation as a personality researcher when he answered a call from Harvard. Shortly before, someone had given Leary magic mushrooms while he was vacationing in Mexico. Leary said he learned more about the human psyche during those four hours by the pool than he had learned during his entire career as a psychologist. At his new post, he started the Harvard Psilocybin Project, where he gave subjects large doses of psilocybin and observed what happened. People like Leary believed that psilocybin could not only cure a single individual, but an entire society.

They thought if they could get four million Americans on acid, that would be the critical mass to start a revolution.

And they were right, to some extent. LSD did change society in profound ways. It’s not without reason that Richard Nixon called Timothy Leary the most dangerous man in America. It’s hard to imagine the counterculture without psychedelics. Perhaps the Vietnam War would have led to some kind of reaction – but when else in history have so many young people refused when told to go off to war? That had never happened before. Eighteen-year-olds normally do what they’re told.

At the end of the 60s, most of the research projects were shut down. LSD and psilocybin were banned. A “moral panic,” as you call it, set in.

The substances elicited fear, especially in governments and with parents. And there were casual ties: people fell out of windows, ran into traffic, reacted psychotically under the wrong conditions, and ended up in psychwards.

Our western value system seems to be somewhat in decline. A lot of people believe we are living in crazy times. Could this explain the reawakened interest in these substances?

The interest in my book suggests to me it did speak to some need that’s out there right now. Yes, we are living in strange times. In western societies I think there is a sense of being trapped in destructive, inescapable patterns, whether they are personal or political. Look at the rates of addiction, depression, or suicide: they’re all rising. So there is a sense of being stuck, and LSD and psilocybin can unstick people. They break habits of thought and behavioral conventions.

A small dose of LSD in the water supply would help us to solve the crippling struggles of identity, the struggles between the elites and the forgotten, between city and country, genders, ethnicities, and backgrounds?

The two biggest problems that we are facing as a civilization are the environmental crisis and tribalism – the collapse of social commitment. They are very similar phenomena. They both involve objectifying the “other.” They are both egotistical frames of mind where the ego is erecting walls between us, whether it’s between people and nature or between people of different religions, ethnicities, or political convictions. It’s always: “I am here. And the others are over there.” Psychedelic drugs seem to pretty reliably attack those misconceptions. You discover you are connected to everything, only an animal in nature. Our sense of otherness is a construction. And psychedelic substances tend to dissolve it.

Is this conjecture, or do we know this?

This has been studied. Researchers at Imperial College London have found that on a scale in psychology [used to measure] where you are with regard to nature, nature connectedness increases in the brain when under the influence of psilocybin. At the same time, people’s tolerance for authoritarianism goes down. This could be the drug we need right now. And there are people who take it regularly in small dosages.

What people?

It’s very popular in Silicon Valley and around San Francisco right now. It’s called microdosing. I know people who take a small dose of LSD every third or fourth day. Only ten micrograms, about a tenth of a normal dose. It’s not enough to really feel it very strongly, but people swear it enhances their productivity and their empathy, and encourages their creativity. It’s a brain tonic. They feel this originally very disruptive drug gives them an edge at work.

Why does Silicon Valley culture have such an affinity to psychedelics?

The history goes back to the early 50s, to the beginnings of the personal computer. A computer engineer from Silicon Valley told me that computer research is often about discovering patterns among many variables. LSD helps you discover patterns in the chaos.

Is what you saw and experienced on your trips just as real, or perhaps even more real, than the filtered reality in which we are conducting this interview? And wouldn’t that be a kind of relativism that would endanger everything?

Consensus reality is a meaningful thing. And I wouldn’t say that psilocybin experiences exist in equivalence with our perceived reality. If right now you turned into a Native American – which is what I saw in Mary on my psilocybin trip – but nobody else saw that happen, then I think we could say that was hallucination on my part and not consider it as the manifestation of some different but equal reality.

But what is it then?

The experiences on a trip are a reminder that a lot of what we see and consider to be real is a product of the mind. If you and I could exchange consciousnesses, we would gradually perceive different things. Our models of the world and the predictions we make are based, among other things, on the fact that you grew up in Germany in the 1980s and I grew up in the USA in the 60s. Your models are slightly different than mine. So far, there is no convincing theory about how the brain produces consciousness – if it does that at all. A number of psychedelics researchers believe that’s merely a hypothesis. I tend to think it’s the most parsimonious so far, but there are many people who believe that consciousness is a property of the universe, like electromagnetism or gravity. It’s out there, and we just tune in.

Would you recommend taking an LSD or psilocybin trip? Is that the message of your book?

No. These medicines are not for everyone. For example, people at risk of schizophrenia or those on SSRI antidepressants shouldn’t take them.

So, no?

That said, there are millions of people who stand to benefit from psychedelic experience, whether they are struggling with addictions, depression, or anxiety, or are well but want to be better. The medicines have great value, but things can go wrong – there are real risks – so to recommend them across the board would be foolish and irresponsible.

You even smoked the venom of a Mexican toad as part of your experiments on yourself.

The Mexican Sonoran Desert toad. You smoke the crystals of the venom, which are no longer poisonous. All that remains is the molecule 5MeODMT, the strongest and fastest acting psychotropic substance. That was pretty scary. The only good thing about the trip was that it was short, maybe 30 minutes.

Psychedelic crack.

It was incoherent. It was just this mental hurricane in my head. I couldn’t orient myself anymore. Not only had my sense of self exploded, but my sense of space, my sense of time had disappeared too. No more coordinates. I was thinking, “Is this what death is like?” I had left everything that felt familiar to me. It was absolutely terrifying.

Any insight?

Afterwards I had a strong sense of gratitude. Not only that I am alive, but that anything exists at all.

Credits

- Interview: PHILIPP OEHMKE

- Images: MUSHROOMS: THE ART, DESIGN AND FUTURE OF FUNGI