“The Hospital of the Future” : A Speculative Report by OMA

|Reinier de Graaf

If you used to not think too often about hospitals, the past year probably changed that. As governments relied on a complex biopolitical arsenal of restrictions, metrics, and media messaging to remediate the worst of the pandemic, the hospital – its workers, its contents – became prominent as both issue and indicator. The health of nations was measured in the availability of PPE, medical labor, and a new metonym: the bed.

As Covid-19 taught us to rethink travel, work, and communication, it also retrained the media. The public’s already insatiable appetite for information – and for “content,” any content – spiked. News anchors and nighttime talk show hosts broadcast from home; magazines shot celebrities through Zoom. Vogue, among other fashion titles, cast essential workers, not supermodels, as cover stars. Through the masked faces of doctors and nurses, the vocational replaced the aspirational. But what about the infrastructural?

It’s time to re-envision the unloved, essential public institution. Another swiftly forgotten marvel of the Covid era: the temporary hospitals built, thanks to military expertise, in parks, stadiums, and convention centers in countries with privatized healthcare systems – and their subsequent decommissioning, which left too few intensive care units to cope with subsequent viral waves.

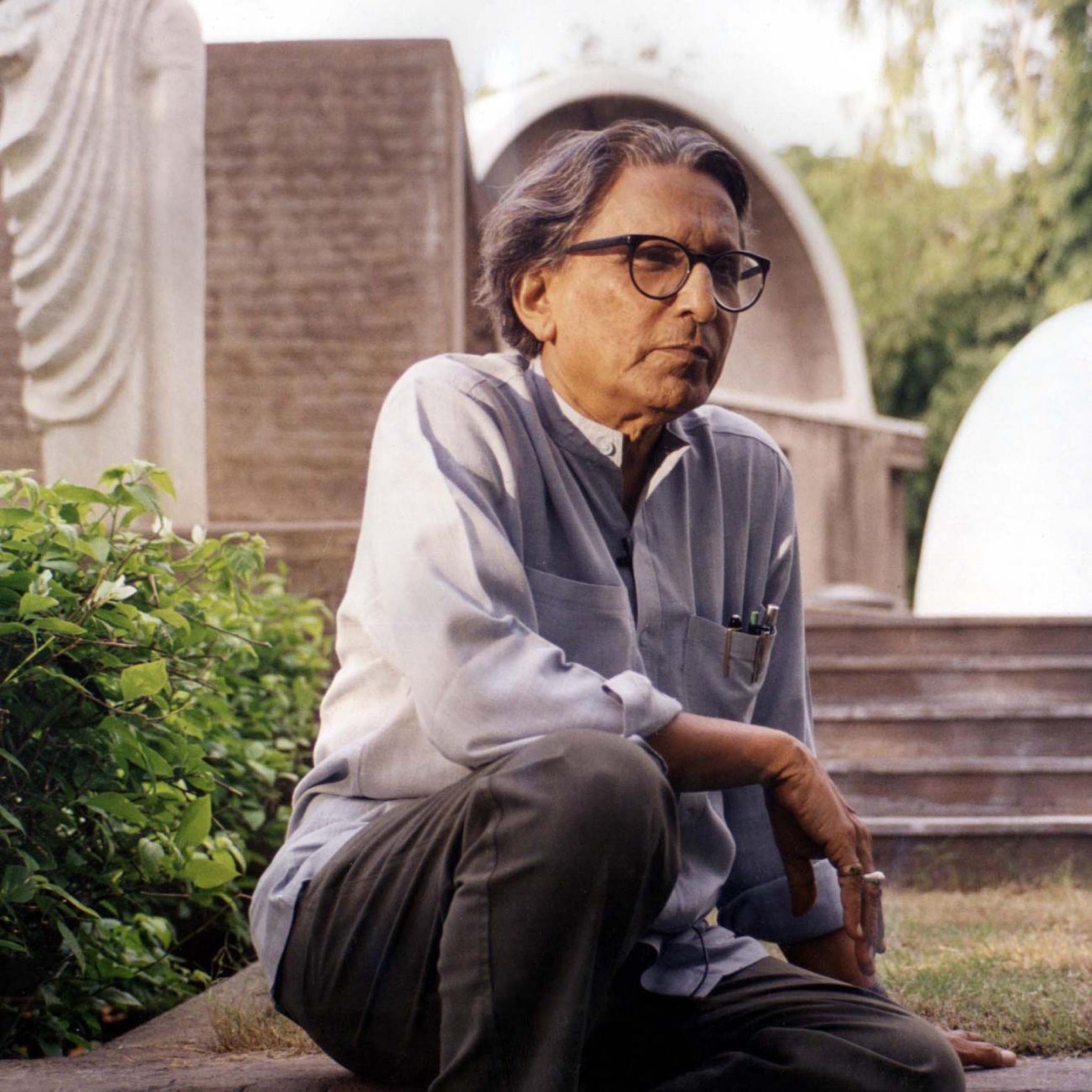

In a 2006 cover dossier for 032c, Rem Koolhaas predicted that the EU would, from then on, “be bold, explicit, popular.” In our Winter 2012/13 issue, the architect and AMO – the research arm of his firm, OMA – speculated that the countryside would replace the city as the focal point of public design consciousness. Now, we publish a third prognosis by OMA/AMO, in which the hospital is considered both as a design problem and as an architectural clue to evolving sociopolitical attitudes toward both public and personal health. Examining what got us here – and where the hospital, as built and conceptual space, will go next – the report reveals a modern institution of mutable form and function. Today, as new attitudes and technologies emerge alongside novel viruses, the research team, introduced by OMA partner Reiner de Graaf, asks: what could the hospital be, tomorrow?

I don’t like hospitals. Surely, I’m not the only one. Why would anyone like hospitals? One doesn’t exactly go to the hospital by choice. Unless you work there, of course – but even then I have the feeling the same applies. So far, I have been fortunate. The times I’ve been in a hospital for anything related to my own health can be counted on the fingers of one hand. And yet, with each instance came existential questions. Do I really want to know what I’m about to learn? Will knowing what I suffer from affect my ability to deal with it? Will life ever be the same after? A visit to the hospital brings an inescapable confrontation with the truth. There is nothing good about bad news, not even for the most creative interpreter. There is no room for speculation. Alternative outcomes are heartlessly dismissed. The hospital is unforgiving.

Equally unforgiving is designing a hospital. One mistake on the part of the architect and someone’s life is in danger. Propose too long a corridor and the doctor arrives (too) late at the patient’s bed. Choose the wrong finishes and infections proliferate. One door opening in the wrong direction could prove fatal in the event of an emergency. In hospital design, architecture stops being a matter of taste. Architecture and technology find themselves in an arranged marriage that is impossible to break. There is zero tolerance for frivolity. The architect’s choices are obelized, without fail and without mercy. In the hospital, the question of whether architecture is a form of art finds its brutal answer: It isn’t!

How then, should architecture approach the “art” of hospital design? How can we apply our skills to a field that prefers detailed briefs over tantalizing visions, where design requires evidence, and concepts manifest in Excel? Has the hospital come to defy creative exploration? When was the last time a hospital featured as a manifesto of architecture? One hundred years ago, medical theory inspired architects to formulate the triad of light, and air, which defined an architecture style that took over the world for half a century or so. What inspiration can architects take from today’s discoveries in medicine and science?

The encounter with the hospital is a daily routine for many. Life-long treatment has allowed an increasing number of previously terminal diseases to be contained. At the same time, new diseases – or conditions – are continuously being discovered. The healthy versus sick distinction is becoming blurred. One day, we may no longer know the difference between one and the other. The world is heading towards a future in which we will all be patients.

What should we do with the hospital? Should we try to make it an enjoyable experience for everyone – a “hospitable” place, as the origin of the word “hospital” indicates it once must have been? Or, should we get rid of the hospital altogether and receive our treatment in the comfort of our home, just as we did no more than years ago, when the hospital as we know it today did not exist? Might the hospital disappear as decisively as it once emerged? In the context of the current pandemic, it doesn’t look like that might happen any time soon. Until then, we may simply have to learn to like the hospital.

Credits

- Text: Reinier de Graaf