The Hospital of the Future: OMA at the Venice Biennale

|Andrew Pasquier

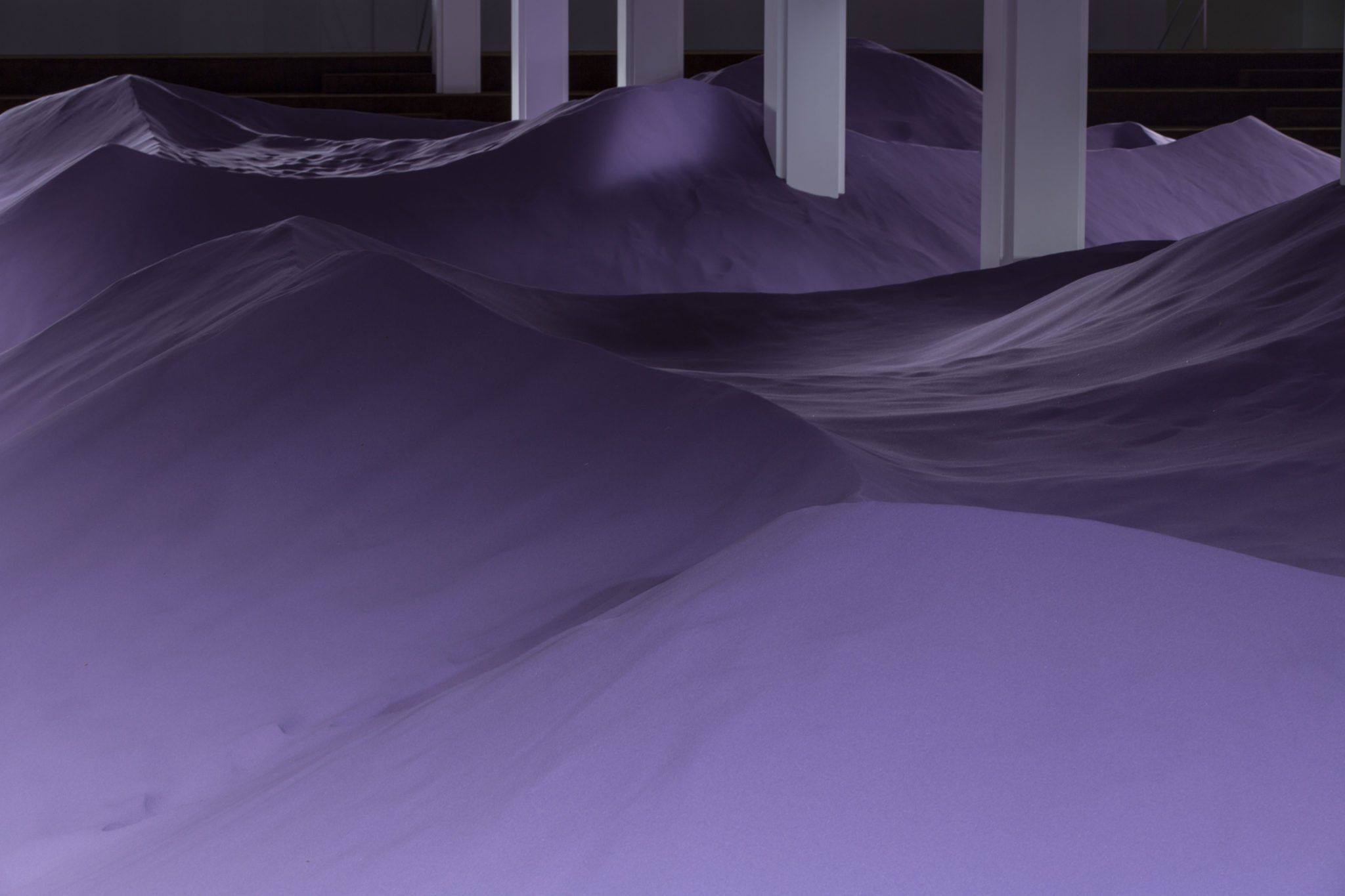

As OMA partner Reinier de Graaf suggests in his introduction to the 032c Issue #39 cover dossier, “The Hospital of the Future,” hospitals can be rather inhospitable places – despite the etymology. OMA began exploring (and seeking to improve upon) the problems and paradigms at the intersection of architecture and healthcare before the outbreak of Covid-19. The project has since unfolded alongside the pandemic, as hospitals – and the amount of beds and equipment inside them – became the metric by which the health of entire nations was quantified. After appearing in 032c magazine this summer, OMA’s research and future provocations have also taken form as an installation at the 17th Biennale di Architettura in Venice, where curator Hashim Sarkis called upon architects “to imagine spaces in which we can generously live together.” Shrouded mysteriously behind a row of medical screens at the very end of the Arsenale, OMA’s contribution invited visitors to lay down on actual hospital beds and trimmings, providing a somewhat unsettling clinical environment in which to view the video created for the project. Joined by team members Hans Larsson and Alexandru Retegan, De Graaf spoke to Andrew Pasquier about the exhibition, and the evolving contexts and contents of the hospital of the future.

ANDREW PASQUIER: Could you describe OMA’s installation in Venice? What did you hope to achieve by recreating the aesthetic experience of a hospital in the Arsenale?

Hans Larsson: Our intervention looks like a temporary hospital ward located at the end of the long Corderie space in the Arsenale. Over the course of the 20th century, life expectancy has risen to unprecedented levels, but so has the burden of chronic, lifestyle-related disease; we wanted to hint that we are all more likely to be patients in an endless hospital one day. The ward, with its oversized curtains and military beds, serves as cinema for our film The Hospital of the Future. The space can also provide a much-needed moment of respite in an event that, with every edition, becomes more and more packed with information.

Reinier, you wrote “I don’t like hospitals very much” in the introductory letter to the 032c dossier. How can architects soften this psychological aversion? How much does the aesthetic and architectural experience of a hospital really matter if – as you also suggest – the efficient medical functioning of the institution is paramount?

Reinier de Graaf: I have the feeling that the more you try to “soften” the aversion to hospitals the worse the experience in the hospital gets. “Friendly” colors in the waiting rooms, prints with smiling people, wall art, potted plants – they all are like adding extra toppings on a bad dish. You don’t go to the hospital because you like it and no cosmetic operation on its interior is likely to change that. Perhaps the hospital should just embrace what it is, rid itself of unnecessary paraphernalia and keep its design honest and clear-cut – go through a sort of iconoclast revolution like the Beeldenstorm in the 16th century.

The uneasiness you get in the hospital is also induced by the restless pace of the people that work there. Much of the drive to “soften” the interior comes from the perspective of the patient, ignoring the staff who really need a functional space to do their job. But maybe more than merely focusing on spatial needs, something can be done to limit the amount of routine tasks doctors and other hospital staff have to perform. Many of these tasks lend themselves for automation; that would give the people who work in the hospital more time with the patients or to simply relax.

Do you think the hospital will vanish as we know it? If so, how soon?

Alex Retegan: One thing we have learned from this pandemic is that we don’t have enough hospitals and in the hospitals that we have there isn’t enough capacity for unexpected events. There have been warnings that a pandemic like this might come and there may be others to follow. The idea that infectious diseases are a thing of the past and chronic diseases are what shapes the way the hospital will work in the future is under question. Even with the travel restrictions imposed during the peak of the pandemic, new mutations of the coronavirus traveled almost as fast as digital viruses. Globalization has reached the point where no one is safe from disease outbreaks no matter where they happen; if only for that reason, the hospital as we know it is likely to stick around for the time being.

While countries have been cutting funding for hospital beds for years – as graphed in the dossier – suddenly we are building temporary field hospitals during the pandemic. Do you think the coronavirus pandemic will change society’s relationship to the hospital?

HL: The pandemic has created a situation where our everyday actions have been drastically reduced or modified, all in the name of health and in the name of protecting our healthcare systems. Vaccine skeptics and libertarians aside, this equation of personal and social behavior with collective health will hopefully create the awareness necessary to counter the trend we have seen in recent decades: the hospital as an efficient business enterprise. Whether we see a new social contract of health remains to be seen – and is probably related to how long the pandemic sticks around, unfortunately.

What’s the most interesting reaction you’ve received to the Hospital of the Future installation in Venice?

AR: At some point during the pandemic, when it was clear that the Biennale would be postponed, we had a moment where we wondered whether having a hospital ward in the Arsenale would be taken as a bad joke. After the opening we saw people were queuing to sit on the beds and watch the film and that was the most rewarding reaction we could receive.

Where does this project, and OMA’s interest in healthcare design, go from here?

RdG: We will soon reveal the design for a self-sufficient hospital prototype which embodies several observations from our research. It will be a low-rise, modular structure, in which technology and nature will coexist.

The 032c dossier and Biennale video both make four predictions about the hospital of the future – that hospitals will “be more human”, “be with you at home”, “make what it needs”, and “know what you need”. Which of these four predictions is most alarming and which one is most comforting in your view?

HL: They aren’t predictions, they are existing trends – although not all yet fully explored in healthcare – and all of them can be both comforting and alarming. We portrayed each with a dose of irony. By imagining a hospital full of robots, we think that it could become more human for its patients and its staff. A hospital that is with you at home speculates on the potential of telemedicine. A hospital that knows what you need alludes to the ethical questions around collecting and processing data. A hospital that makes what it needs is a critique to the just-in-time management of healthcare operations and the reliance on global supply networks. If adopted solely in the name of profitability – like many ideas from the recent past – there’s plenty of cause for concern.

Credits

- Interview: Andrew Pasquier

- Photography: Riccardo de Vecchi