Countryside by REM KOOLHAAS (Part I)

|Rem Koolhaas

It has become an enormous cliché that half of mankind now lives in the city, and that this proportion is only increasing. This has, ironically, been a pretext for architects to focus only on the city. My office OMA/AMO was perhaps partly responsible for the initial shift, but not for the maelstrom that followed: we are bombarded in architecture books with statistics confirming the ubiquity of the urban condition, while the symmetrical question is ignored: what did those moving to the city leave behind?

The countryside is 98 percent of the world’s surface and 50 percent of mankind lives there. But our preoccupation with cities creates a situation comparable to the beginning of the 18th century, when vast areas of the world were described on maps as terra incognita. Today, the terra incognita is the countryside. In this sense, our focus on the city makes us resemble the diagram of the relative sensitivity of body parts: some areas are swollen and over-represented, others withered and neglected.

The emptying of the countryside is having a more drastic impact than the intensification of the city. While the city becomes more itself, the countryside is transforming into something new: an arena for genetic experimentation, industrialized nostalgia, new patterns of seasonal MIGRATION, massive subsidies, tax incentives, DIGITAL INFORMERS, FLEX FARMING, and species homogenization. It would be difficult to write such a radical inventory of the city.

A Swiss mountain village in the Engadin valley epitomizes many of the changes underway in the European countryside. The village is emptying, its original inhabitants disappearing, but at the same time the village is growing: a simultaneous evacuation and extension. There are strict rules for maintaining the heritage of original buildings but in the end these rules facilitate the conversion of traditional farmhouses into luxurious second homes. If you look between their curtains you see the typical contemporary style of consumption: minimalism, but with an exceptional amount of cushions, as if to accommodate an invisible pain…

When I spoke to the farmers, I came across one who used to be a nuclear scientist in Frankfurt. In a classical Swiss meadow, the driver of the tractor is from Sri Lanka, and the only people in the typical village square are three south Asian women, who are now necessary for maintaining Switzerland, looking after the pets, the kids, and the houses…

We are trying to understand what has happened in the century between Prokudin-Gorsky’s photograph of three women in the Russian countryside in 1909 – a highly stylized, highly ritualized environment – and this scene in the Swiss village square today, which illustrates a radically different condition…

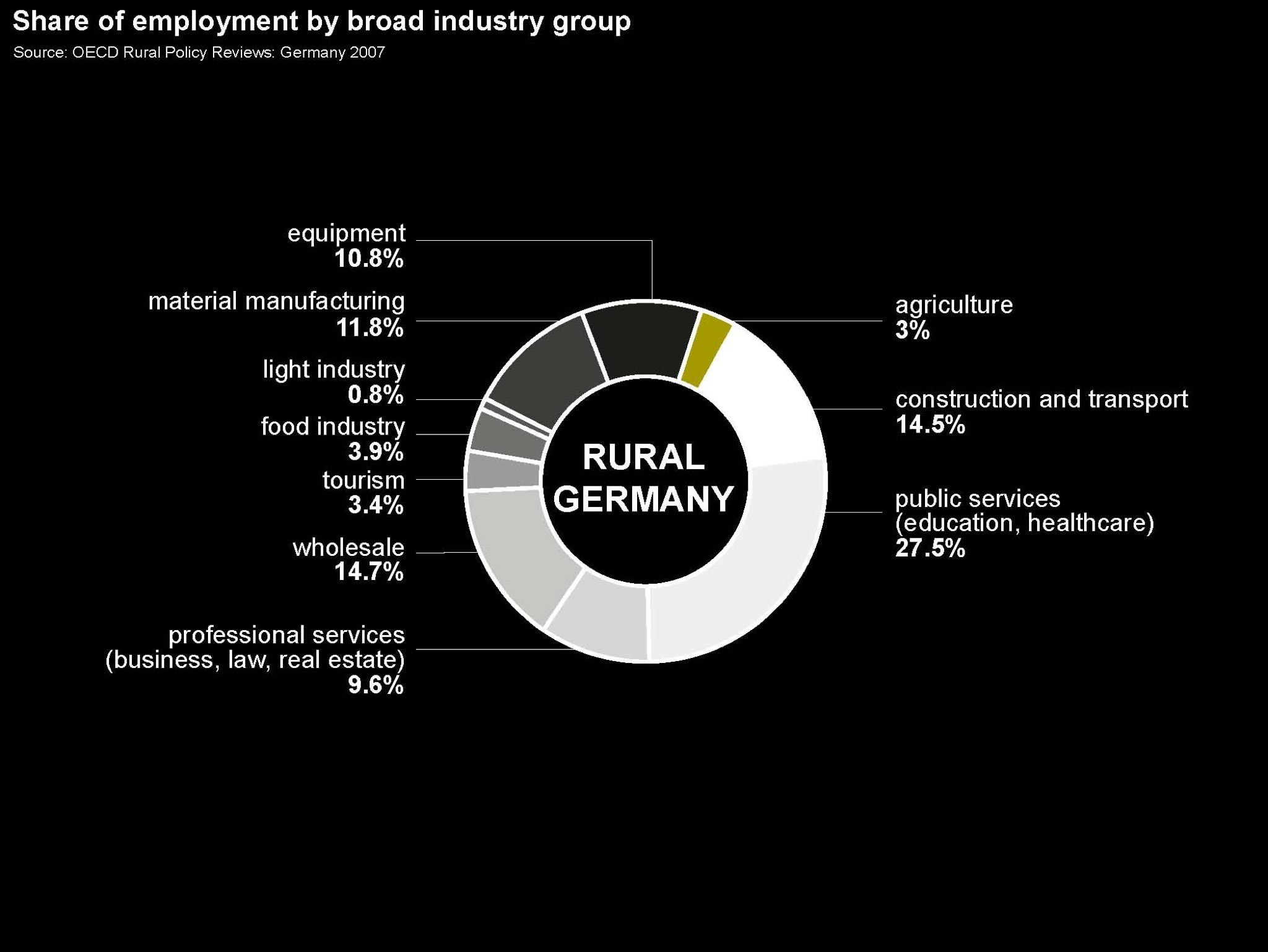

In the midst of rampant urbanization, the world population is still divided roughly 50/50 between city and countryside. In the developing areas of the world, about half of those who live in the countryside still work in agriculture. So even in countries where rural depopulation is a fact, agriculture remains critical. But in Europe and the U.S., the percentage of the rural population working in agriculture is somewhere between two and eight – almost negligible. Globally, if we look at the 50 percent who live outside of cities, there are actually two billion people living in the countryside, not working in agriculture. They live in the countryside and we don’t know what they do there.

To begin making an account, we visited a strip of North Holland, a municipality called De Rijp. It is a classically Dutch landscape. But when we asked people what was happening there, we discovered drastic transformations in the Dutch countryside. These aren’t farms, but a recruitment office, a heritage mill, a yoga studio… Only a few of the strip’s inhabitants are connected to agriculture; the rest form a very contemporary array including a tax consultant, a band member, and an author of children’s books. Most of the landscape is heritage, but inside the preserved buildings, contemporary, “un-rural” activities are unfolding.

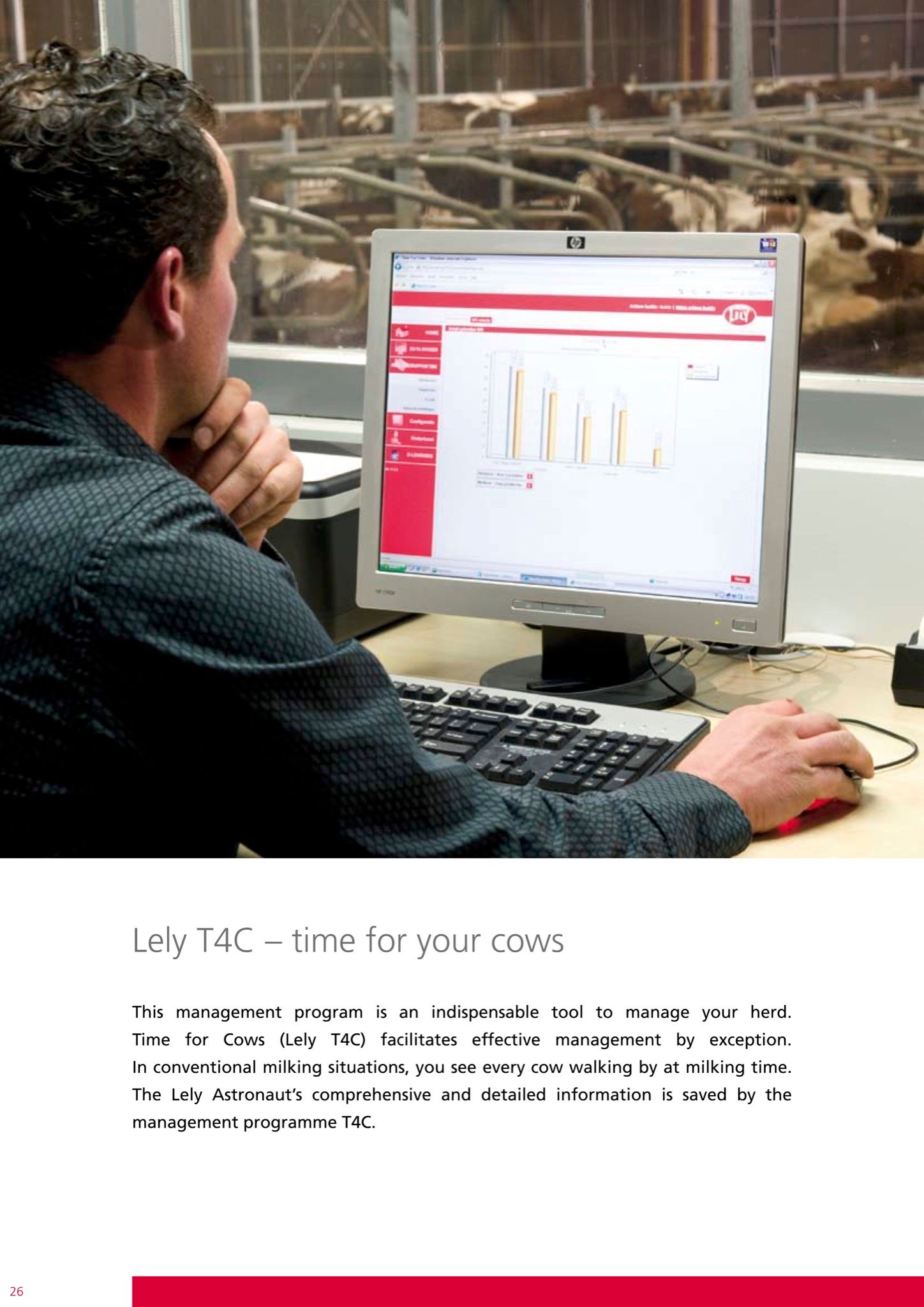

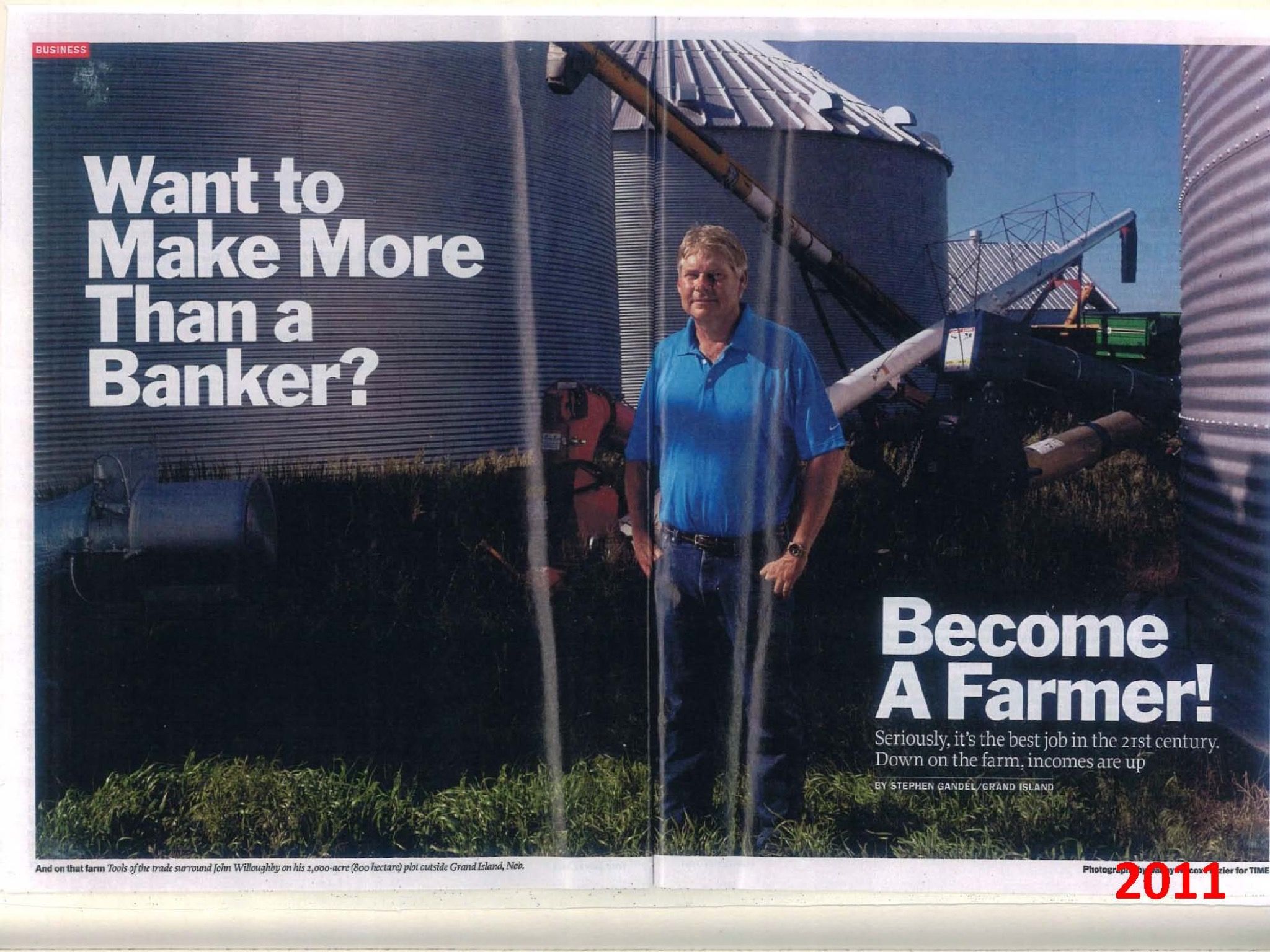

Animal husbandry is increasingly automated: feeding, barn cleaning, and dung removal are taken care of by robots; the farmer has become an office worker, sitting in a cell behind a computer with a one-way mirror to the cows. The information he processes is digital, and in this sense he is like you and me, except that he generates two million liters of milk per year. There is now a paradoxical situation whereby the fewer people that work on a farm, the more it produces. The farmer works with spreadsheets, again like most of us, and if he wants free time away from the barn, there are mobile devices that enable him to leave.

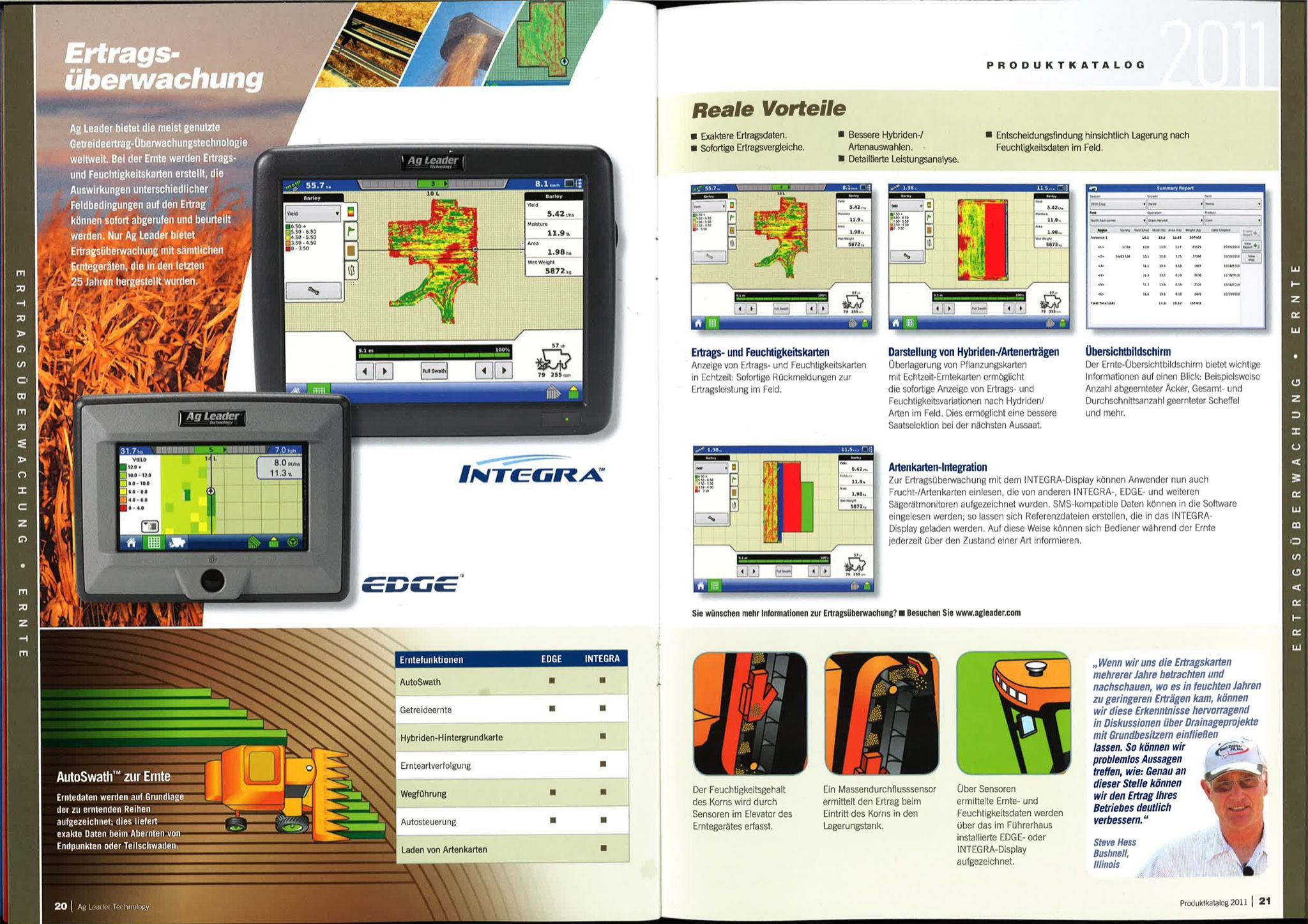

Husbandry of the land is now a digital practice. The tractor, which revolutionized the farm in the 19th century, has become a computerized workstation with a series of devices and sensors that create a seamless digital interface between the driver and the ground. The digital is promising and delivering the ultimate exploitation of the last drop of potential of each patch of ground. Every action, from planting to weeding, is specified for the smallest pixel to generate the largest possible yields. You could even say that landscape and tablet have become identical – the tablet is now the earth that the farmer works with. The countryside is a vast and unending digital field…

The life of the farmer in the 17th century was a stringent sequence of inevitable steps that actually left little time for improvisation. The contemporary farmer’s calendar is a lonely regime of research, server management, administration, and holiday.

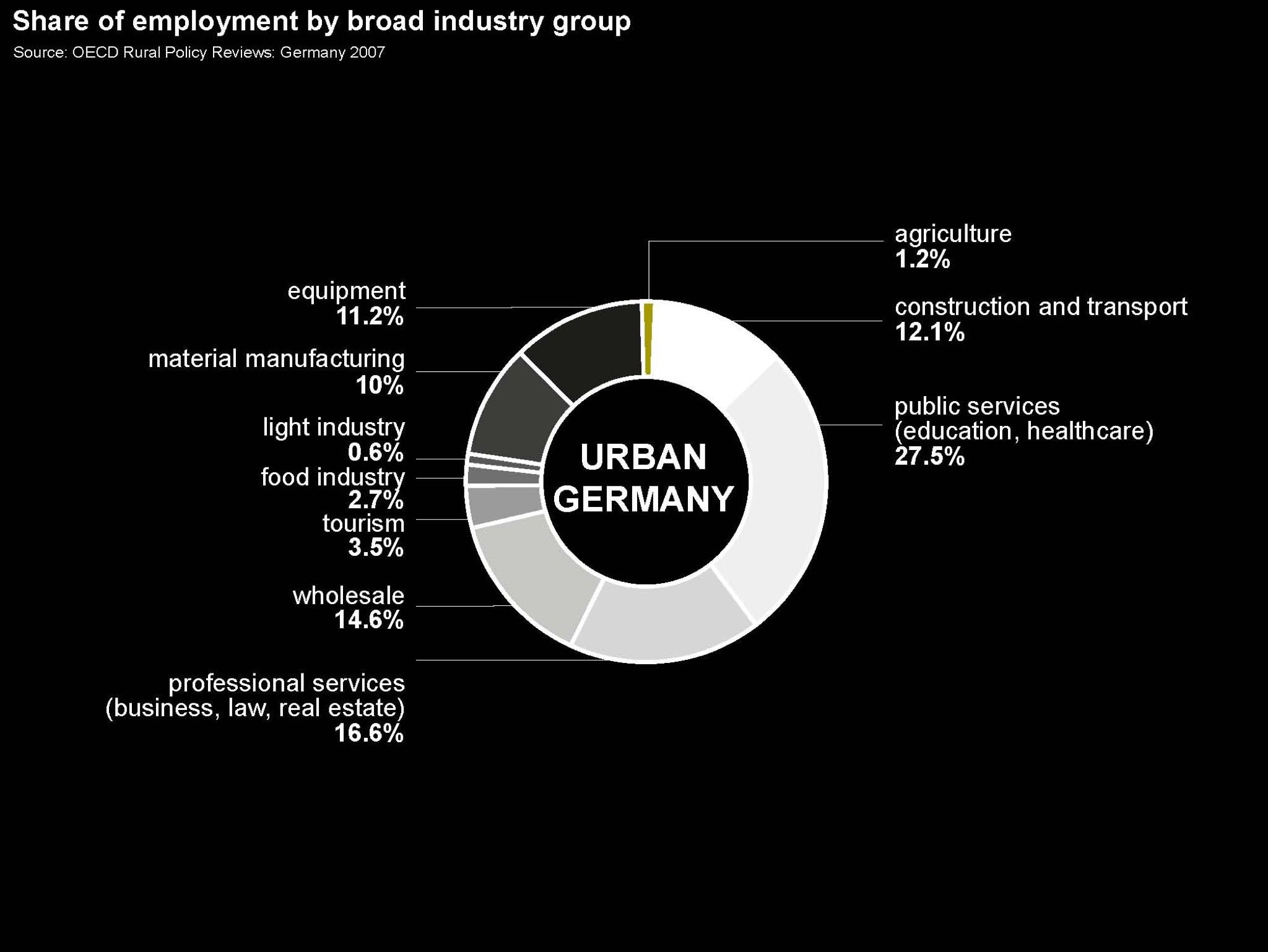

A comparison of the professions in rural Germany today and the professions in urban Germany reveals a huge degree of overlap. The countryside, in terms of how we work, is now very similar to the city. The farmer is us, or we are the farmer. He works on a laptop and can work anywhere. In this, he is like the FLEX worker or the knowledge worker, who is no longer connected to the city and who is discovering the countryside, for very different reasons. The FLEX worker is converting the abandoned farms of the former farmers and turning them into excellent FLEX spaces, where the wooden construction is a very welcome signal of the past, or of continuity.

Europe obviously doesn’t rule anymore, but it does rule the rules. A considerable amount of its rules are exported to other countries and permits them to trade with the E.U. Special software is written to accommodate this kind of interaction creating a new digital frontier in countries very far removed from Europe. One such piece of software, Helveta, enables people in the Amazon to identify and track every single tree in a certain region so that no illegal wood can go to the E.U. Swathes of the Amazon are now carefully inventorized environments where tribesmen-turned-DIGITAL INFORMERS report evidence of illegal logging. Every square meter of this “terra incognita” is actually extremely well known and better known than many parts of the city, even if we don’t know that it is known.

In every part of the U.S., the geometric perfection of farming is blatant, but more surreptitious – and this is almost the same language as missile sites or nuclear sites – are the enormous pigsties that are built in increasing sizes, hidden in the desert, not only in the U.S. but all over the world. This architecture is not only applied to agriculture or livestock; it’s also for server farms. A colossal new order of rigor is appearing everywhere. A feed lot for cows is organized like the most rigid city – the countryside being the ideal situation for these types of conditions; in the city, a monument aspires to formlessness. A HYPER-CARTESIAN order is imposed on the countryside that enables the poeticism and arbitrariness reserved today for cities.

Part of that arbitrariness and poeticism is the city’s production of theories about the countryside. And there are too few people in the countryside to verify these narratives. The countryside becomes a blank sheet on which a narrative can be projected, whether it is a right-wing or left-wing narrative.

One example is the “LAND GRABS” in Africa and how dangerous China is in this respect. Peter Ho, a professor in Leiden, has shown that a miniscule proportion of these stories could be verified and only a relatively modest amount of land was really bought. So what we hear from the countryside is utterly unreliable and utterly manipulated, whether it is good news or bad news.

The countryside is the most contested and emotive field, not least in the new forms of immigration required by new systems in the countryside: an Indian manning a milk farm in Italy, a former construction worker switching to farming in Ireland to accommodate the crisis. There is also an influx or volksverhuizing (MIGRATION) of complete populations. This is becoming an area of intense political protest. We are basically trained at this point to be indignant about workers’ conditions in cities like Dubai, but so far working conditions in the countryside remain unrecorded.

A series of upward trends converge in the countryside: the rise of the market economy, the increase in international tourism, and the growth of heritage sites. This makes perfect sense: you can pay for the heritage sites, and they are necessary for tourism. That means the countryside is becoming a playground not only for NGOs but also for an elite that can enjoy the emptied spaces and re-inhabit the authentic environment of the former farmer and his wife. That happens at enormous scales: entire villages in Tuscany are now bought by German businesses so they can preserve the aura of serenity for tourists.

We try to inhabit this emptiness with remnants of the cultures that used to animate this landscape, and we try to maintain in the name of “INTANGIBLE CULTURAL HERITAGE” the traditions that were once performed. Two different strains of artificiality run parallel. On the one hand the digital artificiality of the countryside today, and on the other the melancholy of the official and artificial maintenance of tradition through organizations like UNESCO.

The polarization of the city and the countryside in our imagination blinds us to similarities, like “THINNING.” Both the city and the countryside are increasingly inhabited in a more provisional way. THINNING is defined by an increase in the area covered and a diminishing intensity in the use of the area. The house in the Swiss village is used two weeks a year, and constantly maintained and partly inhabited by maids from South Asia. But compared to the intensive activity of the people and animals who used to inhabit the village, it’s thin use. There are similar patterns in Dubai. Looking at recently completed buildings, it’s impossible to detect real signs of life. So we looked for the second best thing: signs of irregularity. We found very few. This is the phenomenon of thinning, and it is taking place in both the city and countryside.

The countryside is now a weave of tendencies that are outside our overview and outside our awareness. Our current obsession with only the city is highly irresponsible because you can’t understand the city without understanding the countryside… *

* Taken from a lecture: Oude Lutherse Kerk, Amsterdam, 25 April, 2012

Credits

- Text: Rem Koolhaas