The Hellp: "People have really misconstrued us"

|Cassidy George

“Bring back gatekeeping.”

“Art is basically just masturbation.”

“People have no choice but to act like narcissists.”

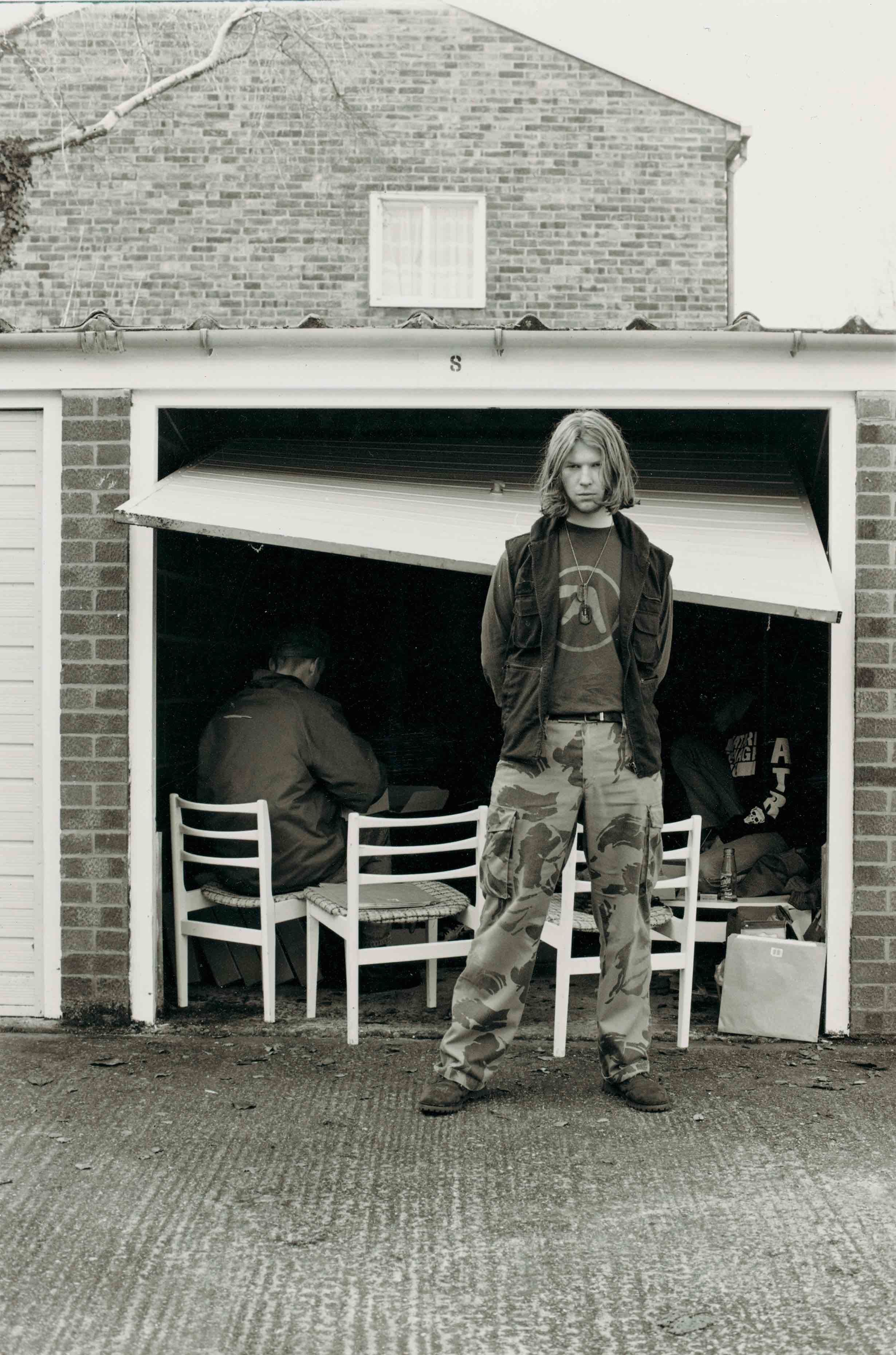

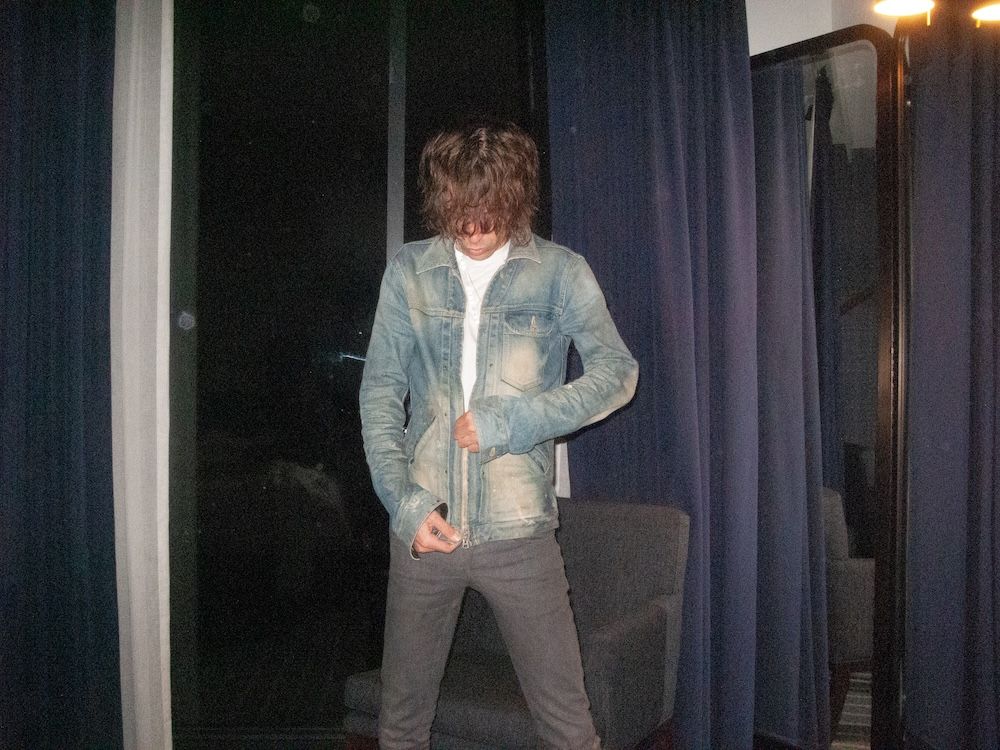

These are just a few of the provocations Noah Dillon and Chandler Ransom Lucy have dropped over the years—statements that, depending on your temperament, might outrage, engage, or awaken you. Dillon, also an acclaimed fashion photographer and visual artist, started The Hellp around a decade ago. At the time, he was most known for his work as a member of the art collective Hot Mess alongside Luka Sabbat. “I felt like I really had to get the fuck out of where I was, physically and mentally. I hated what my life was, so I created the band and other parts of my creative life as an escape route,” said Dillon. The project did manage to hel(l)p him out of his personal hell. Lucy originally joined the three-person band as a drummer, but the two have operated as a dynamic dyad since 2018.

Even a cursory listen to their early discography reveals The Hellp to be early architects of a sound that would come to define the early 2020s—a strain of experimental indie electronica now audible in everything from Brat to the work of Summer 2025 cover star 2hollis. With visual output that is just as crucial to the project as their sonics, the majority of The Hellp’s music videos would look more at home looping on a gallery wall in Tribeca than they do on YouTube. As algorithms continue to only make the viral visible—and, in doing so, accelerate the cheapening, hollowing, and overall idiocy of popular culture—Dillon and Lucy have been unwavering in their commitment to creating meaningful work. For the last 10 years, The Hellp has churned out sounds, images, and ideas that eschew prevailing trends, refute hegemonic discourse, and challenge the general, placated consensus. Ironically, their enduring commitment to swimming upstream will ensure they maintain their role as the architects of dominant culture to come.

While The Hellp’s music works perfectly well on a surface level—anyone can understand the appeal of their most popular tracks “SSX” or “Tu Tu Neurotic”—the project ultimately rewards those who want more. Seekers will find a deep archive of interviews, essays, and even university lectures (Dillon has spoken at Stanford and Yale, among other colleges) that reveal the inner workings of Dillon and Lucy’s processes, philosophies, and politics regarding everything from pant silhouettes to patriarchy and their place within a distorted musical landscape. The Hellp are like the living embodiment of the “iceberg meme”: what’s visible at first glance is merely the summit.

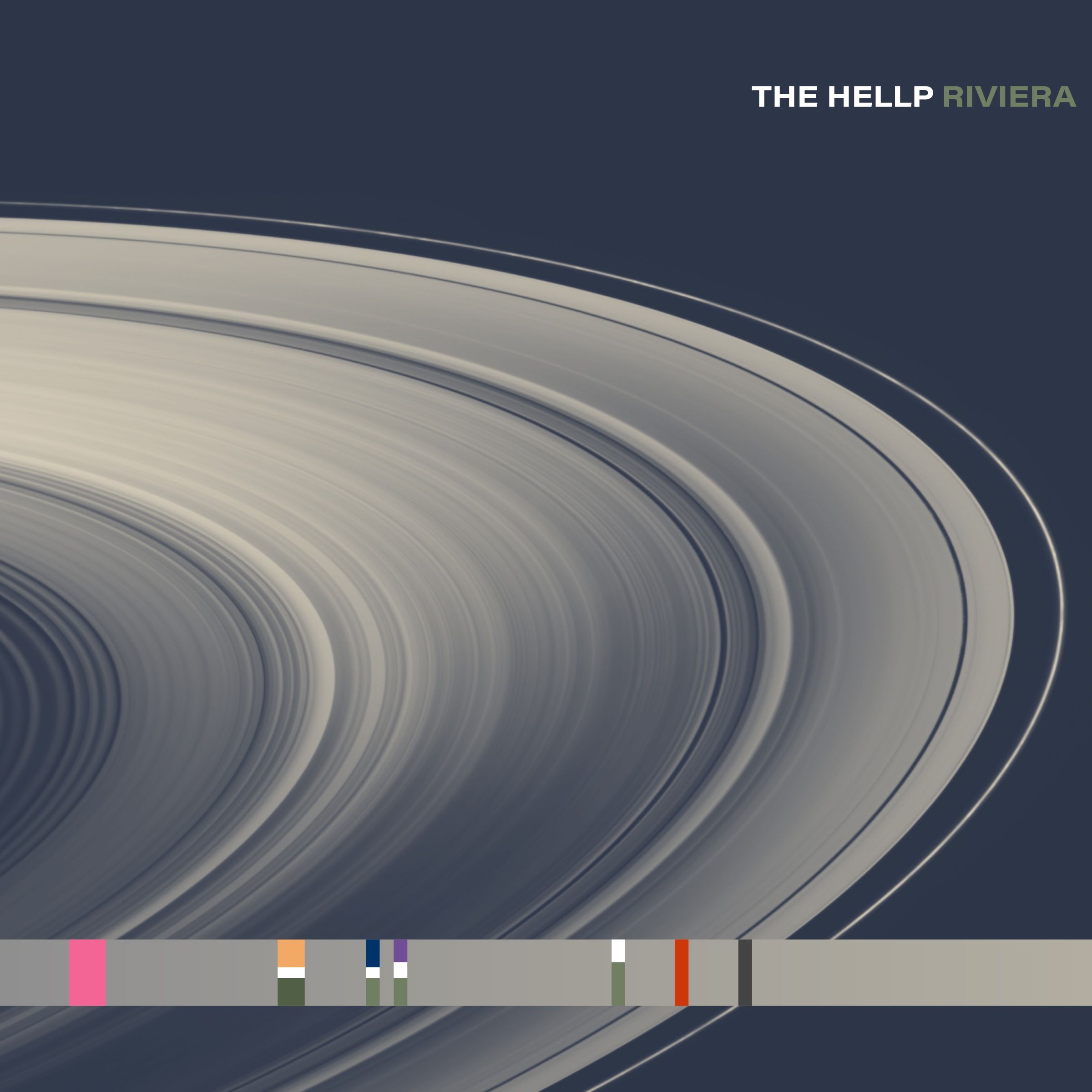

Next month, Dillon and Lucy will release their sophomore album, Riviera. True to form, the duo opened up about the record—and just about everything else—ahead of its release.

Cassidy George: Today you released “Here I Am” as a single. Prior to that you dropped “Doppler,” which is named after the Doppler Effect, right?

Noah Dillon: You got it.

CG: I was really struck by the lyric “Yesterday was just a feeling.” What were you trying to capture with that line, and how does it foreshadow Riviera?

ND: That instrumental is quite old—2018 or 2019. I write the lyrics, and I’m definitely in the era of my life where the things I used to think were so important and worth fighting for don’t seem as pertinent now. It’s actually a freeing feeling going forward. It’s the same feeling the Existentialists had after World War II—disillusionment is rampant. We released a song called “Techno” on an EP a few months ago, which has this line: “Everywhere is something and nothing is everyone.” To me, that’s the same sentiment as “yesterday was just a feeling.” Everything matters and nothing matters at the same time, and you have to push through and stick to your guns—in a way that isn’t self-destructive.

CG: Do you think of The Hellp as a utopian or dystopian project?

ND: I think it’s a utopian project based in a personal dystopia. I started the band in 2015 or 2016. I think the general feeling of media, art, and culture had a more polished and glistening feel—or at least a facade—back then. I could feel the direction things were going in, and I didn’t like where music was heading. I wanted to steer it back the other way. We have steered it, but not necessarily in the direction I wanted it to go.

The core idea of the band is hope, reflection, and positivity. Our “best” song is “SSX,” which is a hyper-indulgent, feel-good song, more or less. The video is basically just me anthologizing my family in ways that I never saw because it’s all footage my dad filmed before I was born. It was about recounting the past so we could have a better future.

Chandler Ransom Lucy: I’m a pretty happy-go-lucky guy, but when we made that demo in 2018, I was going through a terrible breakup with a girlfriend, and I felt incredibly isolated. “Doppler” is a reflection of what’s to come in Riviera, in that there’s a lot of this feeling in the record—a lot of large, rotting landscapes that also feel incredibly isolated. I think the band is utopian in that, even though this record is melancholic and sad, you come out of it realizing there’s still a road to be traveled. Even our darkest records make you feel like you can continue—even for just another day, just to see what tomorrow has to give.

ND: You know, Riviera makes you think of the French Riviera, and that’s obviously the escape people from the North and from Paris made; heading south in the spring and summer. A lot of great French New Wave cinema is based in the Riviera. But if you transpose that idea of escape to America, that’s what the album sounds like. I live around the Echo Park area in LA—and every time I look toward the coast, I see the distant hum of lights from Long Beach, Huntington Beach, and Santa Monica. The American Riviera, that’s what it’s called.

When I was a kid growing up, there was this hill that looked so similar to the Windows XP background—the iconic one that Chandler grew up less than 30 miles away from, coincidentally. I would look over that hill and think, “I know right over that crest there’s a beautiful oasis that would allow me to get away from all of this.” I won’t actually go over it because I know it’s just more land, but if I leave it to be a mystery, then everything is okay. It was like Schrödinger’s cat. And that’s what the riviera is, and what it embodies in this record—melancholy at its finest, but layered with the veneer of hope and fervor.

CG: Just circling back to what you said about Existentialism, I’ve always felt like your band does a good job of sonically articulating feelings of internet-era alienation. What is the antidote to that, in your opinion?

ND: The anodyne doesn’t really exist for me. That’s sort of why I created this band and whatever this lifestyle is that I’m living now. I was just looking for human connection via the expressive arts, I guess. I don’t have an answer yet, I’m still on that journey. Music is a juvenile pursuit. A band is. Starting a band is a common teenager activity. If you’re smart enough—or stupid enough, depending how you look at it—to figure out how to make decent music, then it continues into your adulthood.

CRL: Noah and I both grew up in small, rural towns, and we both felt pretty alienated and rejected. I think that subconsciously has carried through in our behaviors and in the nuances of how we communicate ourselves to the world. What happens to you in your formative years—I guess some people would refer to this as “trauma”—really does stick with you and define you, whether you’re able to carve a path forward for yourself or not.

ND: I didn’t get a taste of what acceptance felt like until my later teens, and then parlayed that into the creative fields. That’s a big bone to chew on, and we’re still gnawing our way through it and around it.

This record has been in my mind for almost eight years. The band actually started with this feeling on the initial works, but then we made an experimental track just for fun, “Tu Tu Neurotic.” This branded the band in a different light. Our Enemy EP (2021) took people by surprise, but then we went to Atlantic Records and became obsessed with the idea of outsider pop music. That’s what most people know the band for now. Enemy is much more in line with how Riviera is going to feel. It’s much more aligned with our self-ontology, who we are as artists today, and how we feel about life.

Our album LL (2024) was much more of a concept record. With LL, we knew we were making something almost tasteless. Or I should say, we were riding a fine line between taste and tastelessness. It was an intentional play on making bangers. We were like, “What’s up, everybody! We’re gonna make bangers just like the kids who we inspired do now.”

To do this I actually tried to give myself brain rot. Every day, I watched as much TikTok and listened to as much SoundCloud as I could, and listened to as many Splice beats as I could. I tried to fry my brain and make it younger and almost stupider, so we could make that style of record. Riviera is the complete opposite approach.

CG: Intentionally rotting your brain in order to make pop music is kind of like method acting, but for music.

ND: It unfortunately really worked—but at what cost? I’m stupid now. I can feel the lag in my brain. Was it worth it? You have to sacrifice something to get something else. So yeah, why not?

CG: I think your candor is part of what makes The Hellp stand out so much. I feel like there isn’t that level of transparency in music anymore. Most artists in your arena are trying to be as mysterious as possible, which, to at least to me, often feels quite cliché and manufactured. I sometimes wonder if it’s just being used as an excuse for artists who have nothing meaningful to say.

ND: It’s all manufactured. We’re manufactured too—it just depends on what level you’re doing it. People love a product, and we’re no different. This band and us as people—we’re products to be consumed. People love when a product is wrapped up in nice packaging, when all the Ts are crossed and the Is are dotted and whatnot.

Since the 1950s, we’ve been used to these hyper-manicured moments and people. Of course, you could say, “What about the Britney Spears crash-out?” Or mention any of the celebrities who’ve gone off the rails in the last 60 or 70 years, but even then, that narrative was crafted by the press and a team of PR people.

Culture moves so fast now, but we’ve been relevant and influential since 2016. That’s a long time for a contemporary act. Beyond the main pinnacles like Charli XCX, we’ve seen everybody come and go in the underground. We’re a bit more raw and rugged, and people are at odds with that sometimes, but I also think that’s why we have been around for so long.

CRL: Being quiet, sparse, and mysterious has only ever worked for two artists: Aphex Twin and Frank Ocean. I believe honesty is always the best policy, and I believe in wearing your heart on your sleeve. To quote David Lynch in a Louie episode: “Look them in the eyes and speak from the heart.”

ND: We’re not really ironic guys at all. I don’t subscribe to that. I’m part of the more “cringe millennial” style of David Foster Wallace and that era of thought. I mean what I say and say what I mean.

We sacrificed everything to be here, and I know you’re not supposed to say that as a white, cisgender male who has all of the—but whatever. I don’t give a shit. I grew up in a fucking tent for a couple of years and lived on an Indian reservation in the middle of nowhere. I’ve had a hard life. And Chandler is no exception.

We’re just guys who worked hard and want to make some cool and beautiful things, and are not afraid to say it. We really want to be great artists because the legacy of music is very important to us. It’s an important flame to have your hand over and carry forward into the future. We hope this new record is able to do that.

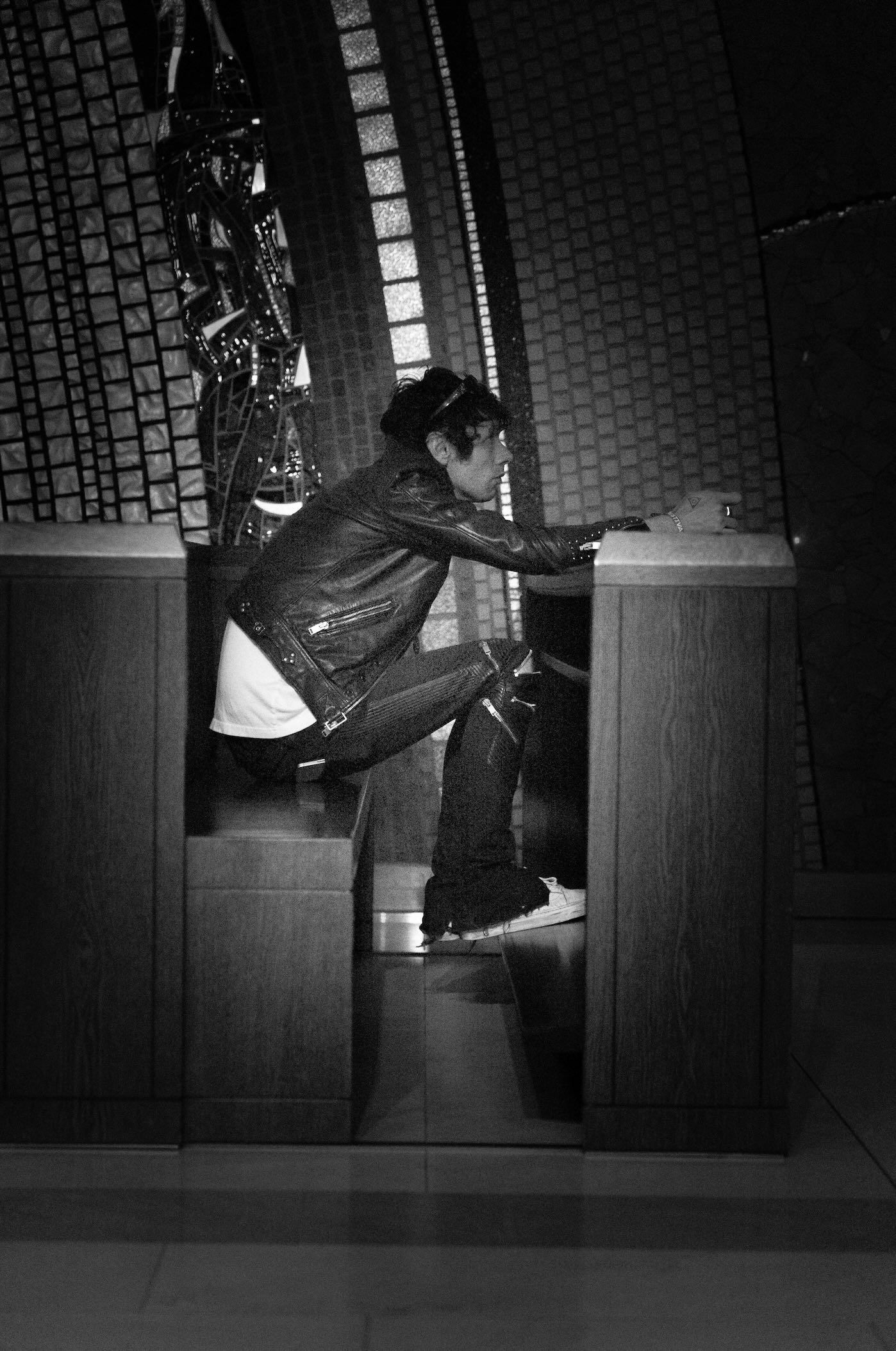

CRL: Our contemporaries don’t really talk candidly. People have really misconstrued us. Recently, there was a quick interview with us at a fashion show, and they were like, “What’s your dream cigarette rotation?” I said a conspiratorial name and Johnny Ramone, and Noah mentioned some pretty reputable historical figures—and all of the comments were like, “Oh, these guys are so annoying. They’re so irony-poisoned.” We were like, “What are you even talking about? Is it because we’re wearing leather jackets?”

I think everybody has been so irony-poisoned. We have been brutally honest in all of our interviews. Whether we agree with what we’ve said 24 hours from now is irrelevant to us. I just don’t think people can really handle that in the modern age. It’s not that people can’t handle the truth, I think it’s that most people don’t really know who they are. When they see a couple of dudes who are comfortable with their beliefs, their only instinct is to throw tomatoes at them and boo.

CG: In my experience, even your most controversial statements from the past are actually proposing complex ideas—ones that are worth ruminating over. They aren’t flippant hot-takes. I appreciate that there is genuine discourse around your project.

ND: I’m really glad you see it that way. I know a large population of people don’t. Intellectualism in general is sort of hated right now, for whatever reason. You can’t expect people to think critically—you have to make the work that allows them to think critically. That’s what a good teacher does: you lead the person on, and then allow them to think they got there on their own.

That’s why we were so obsessed with making “pop” music in a potentially avant-garde way. We think it does more to move the needle of culture than making music that is intellectual at the surface level, specifically because of the times we live in.

We’re in the post-Warholian era of art and commerce and obviously mid-to-late-stage capitalism. To have the conversation cogently and develop rational thoughts about our placement in reality, and to de-disillusion ourselves from the monstrous world that we have now—I think we have to interrogate pieces of media that are very pop-based and pop-structured.

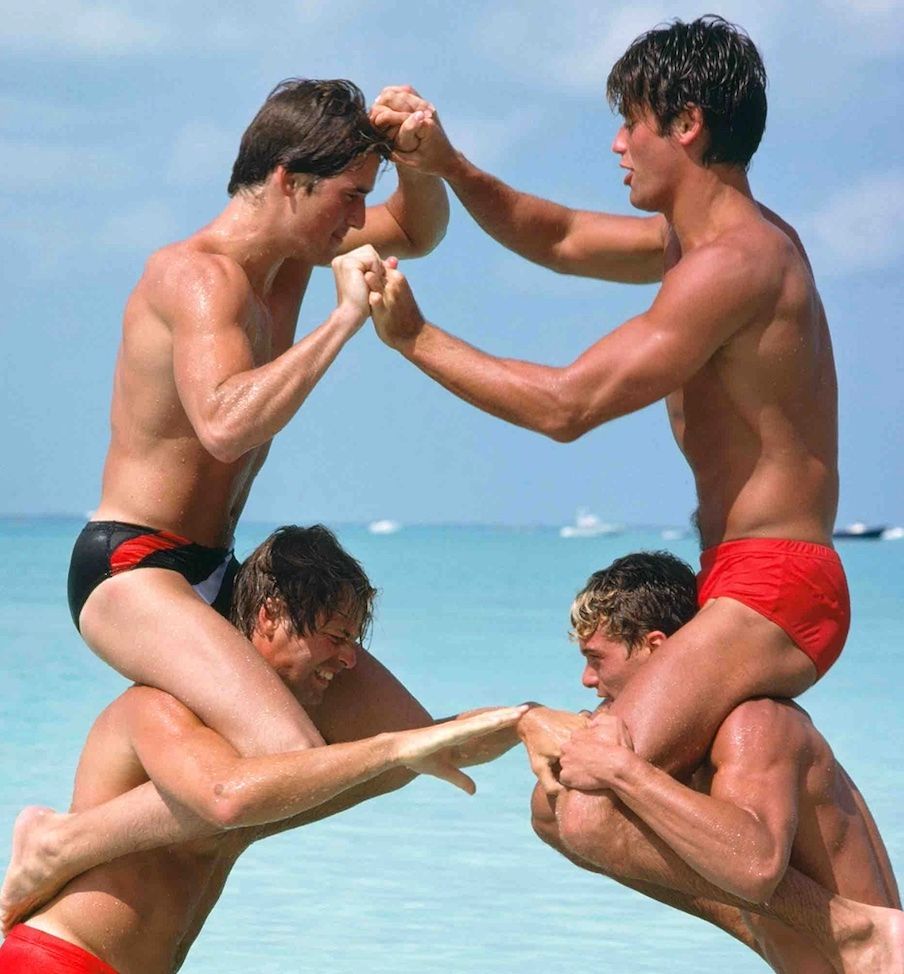

CRL: Using “Caustic” as an example, we have a very unique contrast in what we look like, what our songs sound like, and what our live shows and DJ sets can do. In every other universe we’d be making Justice-style music, or Sebastian—just something cool and hard.

For us to be these guys and make a “California Dream Girl,” and then do this live show where you have these insane moments where you see kids borderline crying in the audience because they love “9_21” so much—and then immediately contrast that with a breakdown at the end that’s a Katy Perry remix at 180 BPM, but still tasteful and doesn’t invalidate what we represent or who we are as people or artists—that’s what makes it interesting.

CG: When you signed to Atlantic, I was worried that the “powers that be” might corrupt the integrity of the project in order to be more marketable. But it sounds like you’ve been able to draw a line in the sand.

ND: We signed, but it kind of gave us a license to be even more brazen. We almost got dropped the first day we got signed. We had a meeting with the bigwigs of Atlantic and Warner—you know, classic boardroom style, high-level office in uptown Manhattan. Chandler and I were looking like Chandler and I always do—we had sunglasses on, and I had my earphones in like I do now. I literally have them in all the time because for one, I have really bad vertigo. Secondly, I just like the feeling of these things in my ears.

Anyway, at this big meeting, half of the people there were trembling in fear because they knew we could say something crazy, and the other half were waiting for us to kiss the ring. One of the execs loved us, and the other exec absolutely despised us. It was apparently the most visceral, negative reaction that this person had in over 25 years of working at the company. This person came to our live show in LA and then they changed their narrative.

CRL: Noah is glossing over the most important detail in this story, which is that we wore our sunglasses the entire seven-hour day at the office. [Laughs.]

CG: People will probably argue in the future that this was all one big piece of performance art.

ND: What did they expect? Of course we’re gonna walk in and say some piped-up shit. That’s just the nature of the music industry. People have forgotten that because everyone loves these controllable objects nowadays. .You’re being monetized from every single angle—but this has always been the case. Why do you think Elvis killed himself? It was like the first great Stanford experiment in pop music history.

People know how the water flows in the entertainment industry. I’ve never even said or admitted that out loud, but I guess it’s true: we are entertainers in the entertainment industry. Shout out to Kurt Cobain for saying that a long time ago—that’s all we are. Everybody’s an entertainer. Every kid with a phone who’s moshing and not even looking at the person on stage, but looking at themselves [on the screen]. Yes, we are doing a performance. We’ve all read Society of the Spectacle (1967). This has been coming for many, many years. Every single one of us is engaging in some degree of performance. But don’t be mad at Chandler and me just because our performance is better than yours.

CRL: That’s some real shit. I think that’s the realest thing you said all month.

Credits

- Text: Cassidy George