Bruce Weber Doesn’t Like Clothes

|Claire Koron Elat

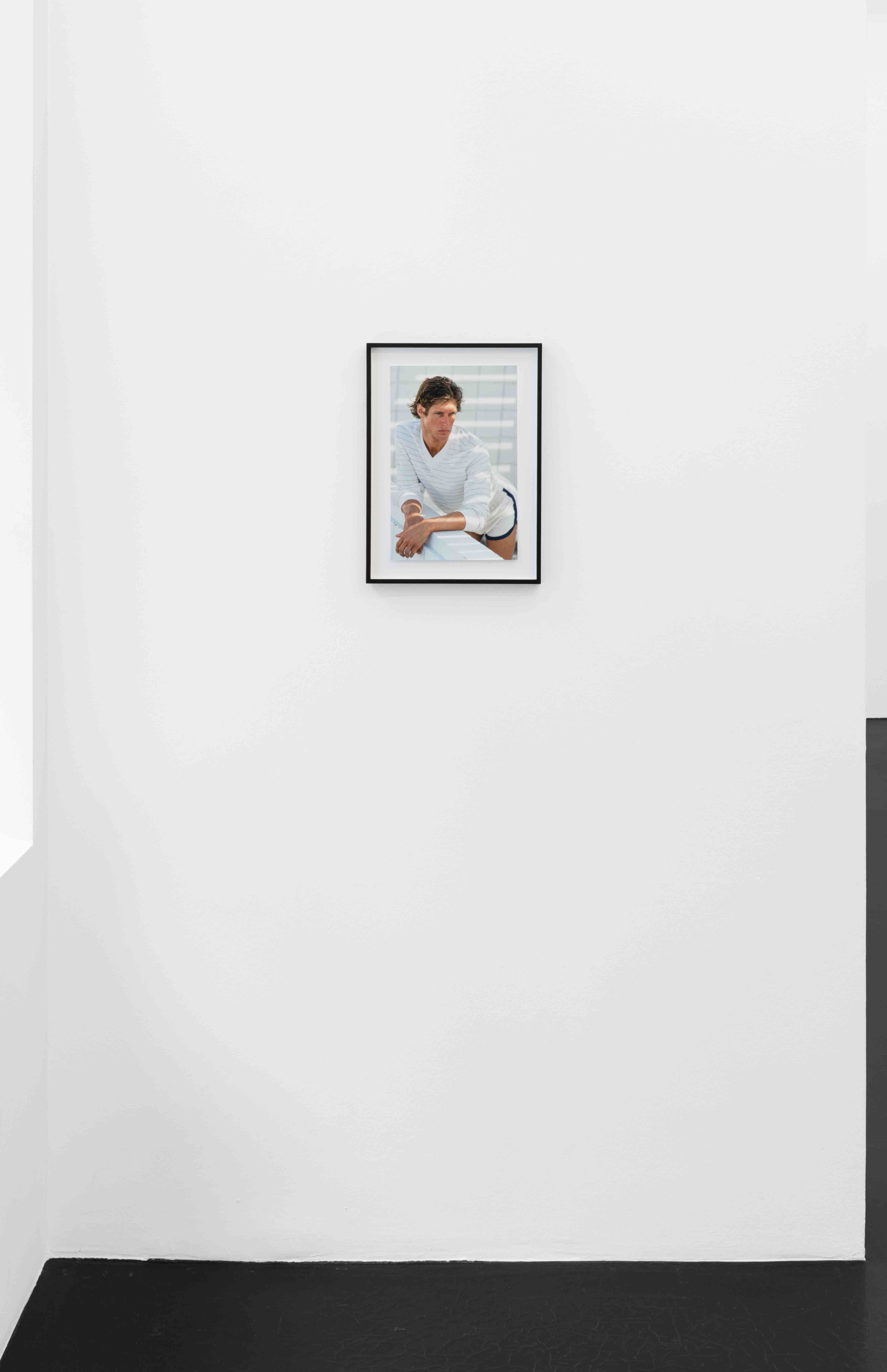

Bruce Weber, “Bahamas”, 1980, archival pigment print, Courtesy of Galerie Buchholz

“For me, photography was never just about fashion—and I find fashion in the most unexpected places,” says American photographer and filmmaker Bruce Weber. In his current solo exhibition at Galerie Buchholz in Cologne, which closes this weekend, he revisits early works from the 70s and 80s that have shaped a new visual language in advertising.

In conversation with Claire Koron Elat, he discusses masculinity and male desire, shooting with amateurs, and George Cukor’s influence on his work.

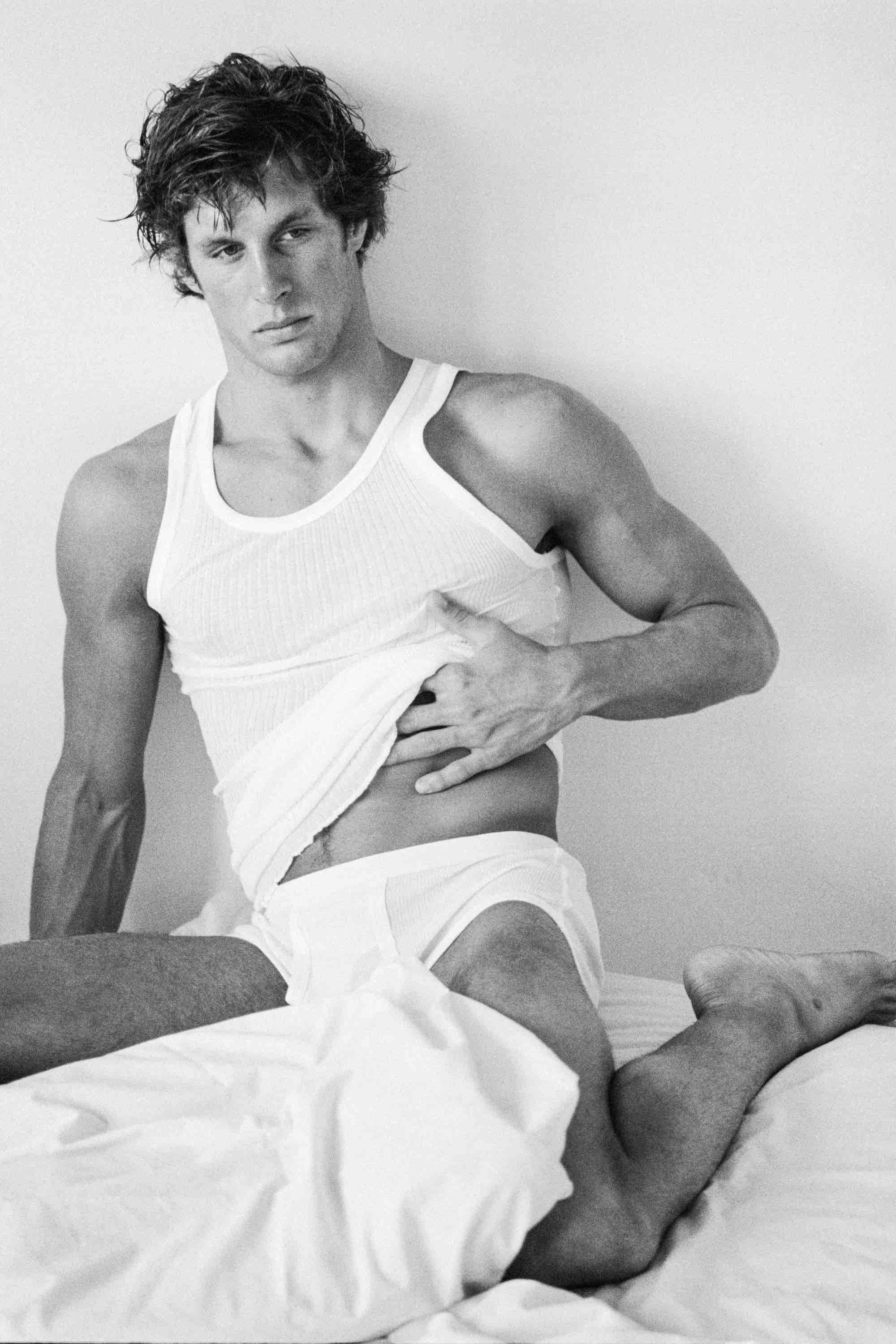

Bruce Weber, “Jeff Aquilon. New York, NY”, 1978, gelatin silver print, Courtesy of Galerie Buchholz

Claire Koron Elat: Your current exhibition “Early Men” at Galerie Buchholz in Cologne presents photographs from your foundational period in the late 1970s and early 80s. These works are lesser-known. Why did you choose to revisit them now and showcase them specifically in a gallery context?

Bruce Weber: Truthfully, I hadn’t thought to re-exhibit them at this moment. The idea started with a good friend of mine, the cinematographer Jeff Preiss, who I worked with on two films years ago: Broken Noses (1987), and Let's Get Lost (1988). Jeff is friendly with Jacob King and Heji Shin. They connected Nathaniel Kilcer, who works in my archives, with Christopher Müller and Daniel Buchholz, and together they looked through lots of older works and proposed we start there.

I got particularly excited when we started reviewing the sittings I had done at George Cukor’s home in Los Angeles back in the late 70’s when I was first starting out. When I heard that Christopher and Daniel responded to that work as well and the idea behind it, I knew we were on the same page.

CKE: The exhibition’s press release also says that Heji Shin and Jacob King had a conversation in which Shin criticized contemporary fashion photography, and said she finds boring. What do you think about fashion photography today? And how would you compare it to fashion photography in the 80s, 90s, and 00s?

BW: It’s a little hard to answer this, because for me, photography was never just about fashion—and I find fashion in the most unexpected places. Sometimes I'll see a photograph of an important ambassador on a state visit, and I think about the clothes they're wearing. I've always felt photography was about everything that our eyes see, or at least what we want to see. I understand Heji’s point, though. Fashion photography today is so different. Back when I started, we were using film. I had a beautiful spectral light meter that was typically used in-cinema. It was my trusted companion, as much as my camera. Now, with digital, it’s different–some of that trial and error is taken out of the equation. But I’m still excited any time I pick up a camera.

I think the biggest difference when I was starting out was the amazing support system backing me up: editors, art directors, stylists and publishers all pushing me to do my best. Young photographers today simply don't have access to networks like that, or the same time to develop those relationships. But I try not to be judgmental about it. I know that photographers are having a good time as always and that people are giving them chances.

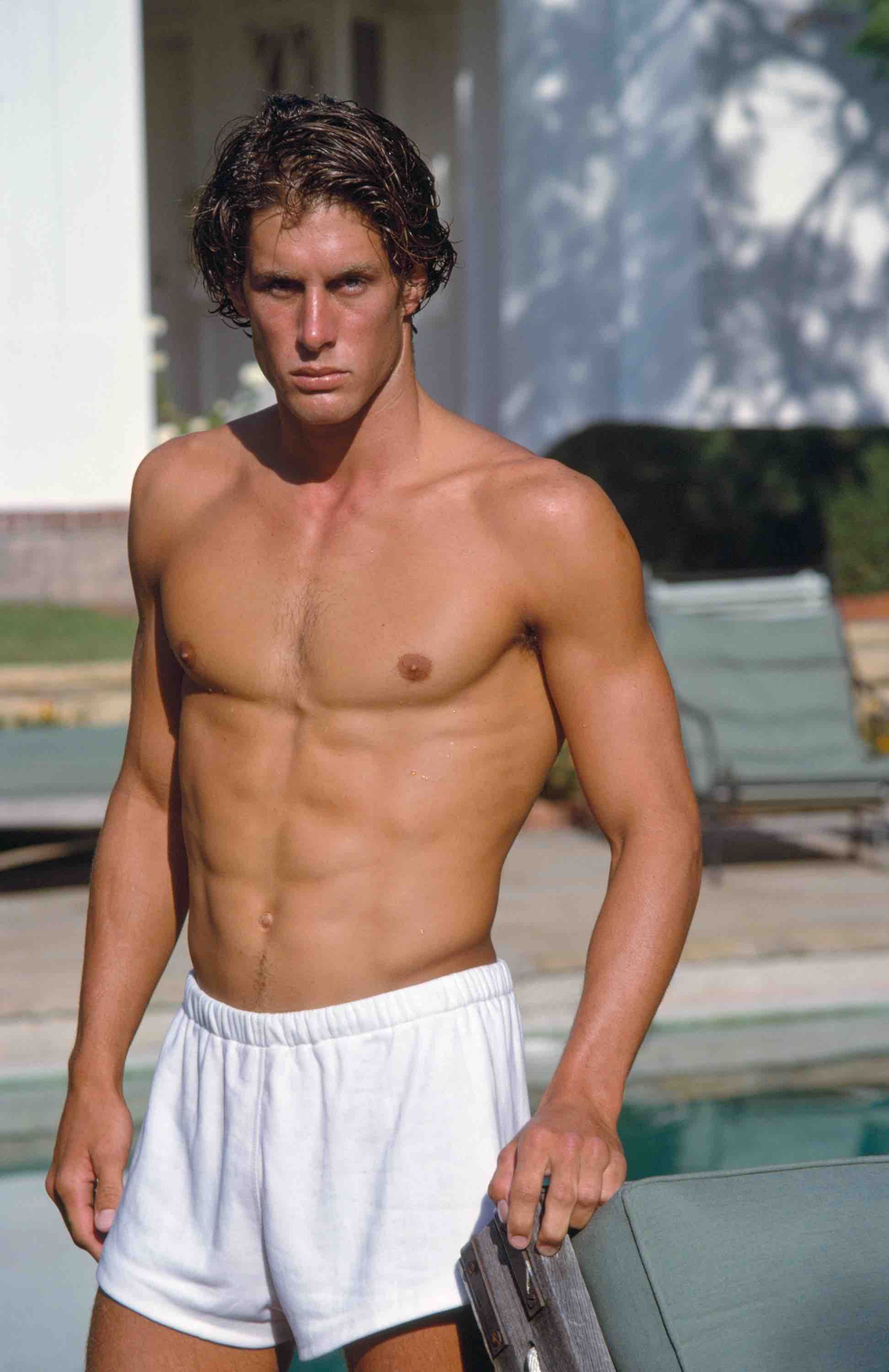

Right: Bruce Weber, “Barbados, W.I.”, 1979, archival pigment print, Courtesy of Galerie Buchholz

Left: Bruce Weber, “UCLA rugby, Los Angeles, California”, 1981, archival pigment print, Courtesy of Galerie Buchholz

CKE: The photographs taken at George Cukor’s house are central to the show. In what ways was this formative for your later work? Was he a mentor for you?

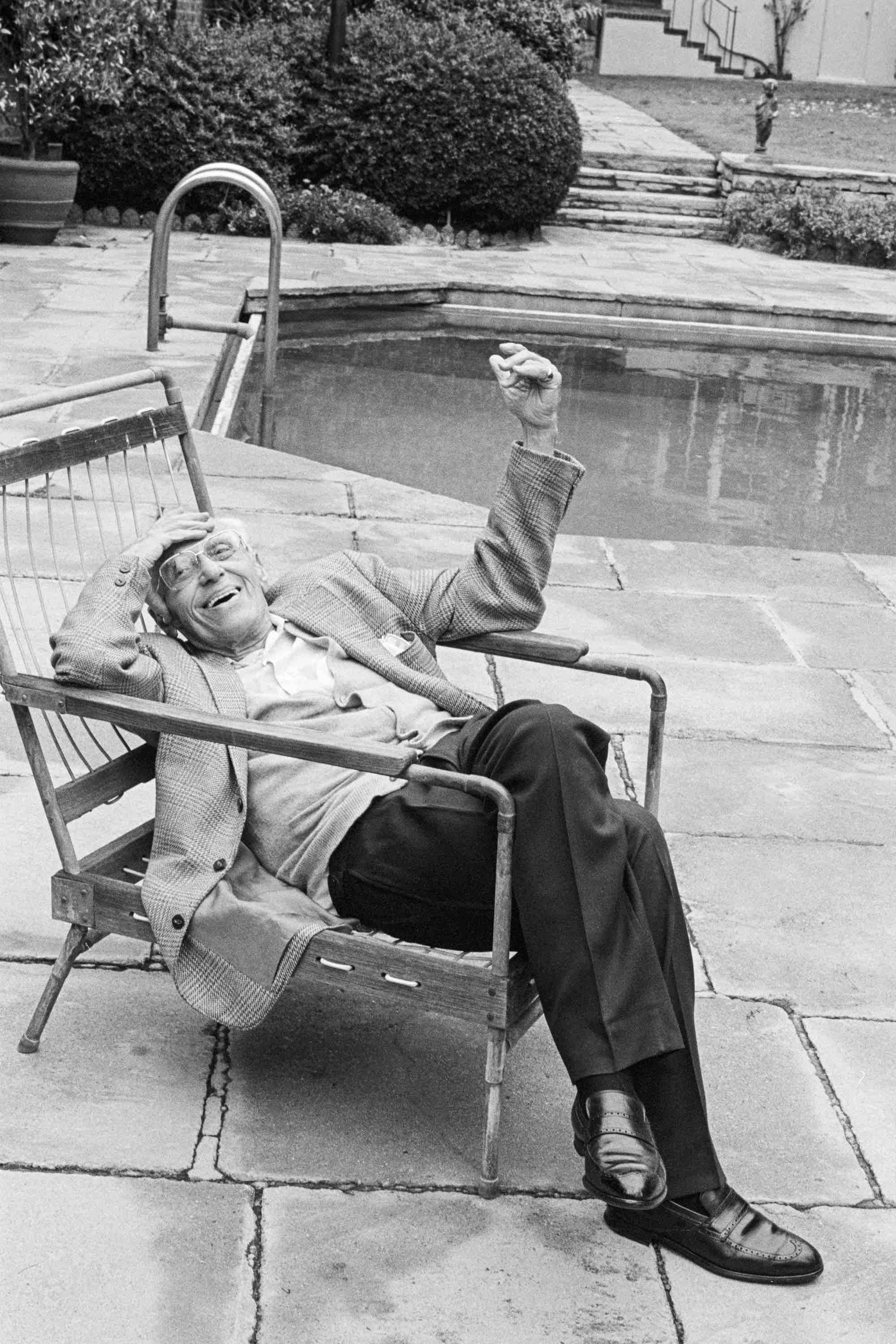

BW: Mr. Cukor was quite a strict man, but he had a good sense of humor. He worked with so many movie stars that my parents really idolized: Katharine Hepburn, John Barrymore, Joan Crawford. So it was so unexpected for me to find myself at his house. I'm calling him Mr. Cukor because when I met him on that first sitting for GQ, and the writer with me called upstairs when we arrived, “George, we're ready for you.” Mr. Cukor came out and said, “You can call Katharine Hepburn ‘Kate,’ but you must me Mr. Cukor.” He was really annoyed about it.

But he was very kind to me for the rest of the day. When we finished, he invited me to come back anytime. A year later, I met a young man by the name of Jeff Aquilon, who was the water polo captain at Pepperdine University. I asked him to come to Mr. Cukor's house because I wanted to take pictures of him in the swimming pool. Mr. Cukor came down and watched as I worked. When Jeff got out of the pool in his red Speedo, Mr. Cukor called out, “Now, that’s Hollywood!”

I'd say Mr. Cukor was a mentor in a way. He was friendly with many older directors that I knew, and I really looked up to him. I loved his movies. People were so idealized in his films. His movies are very different from the movies by another favorite director of mine at that time, John Cassavetes – where everything is so real.

CKE: Did Cukor influence the way you perceived masculinity and male desire?

BW: Because he lived in Hollywood, Mr. Cukor was very secretive about his private life. But he hosted a Sunday brunch at his home that was only attended by men. All of the well-known actors, directors, painters, and writers were there. He unfortunately never invited me—I was probably too square. All the people working at his house were really great looking. From what people told me, it was a sort of a celebrity gallery. I appreciated that Mr, Cukor’s home was his place where he could really be himself. It was a very conservative time, and he was a gay man living in Hollywood. Being as famous of a director as he was, I think it was hard for him to have a private life.

Bruce Weber, “Mr. George Cukor. Hollywood, CA”, 1977, gelatin silver print, Courtesy of Galerie Buchholz

CKE: You pioneered a new form of representation of male bodies in a period when it wasn’t so typical to show them – in advertising, for example.You also often chose to work with non-traditional models. Why did you take that approach?

BW: When I was at Denison University, my parents gave me a Pentax camera. My roommate just happened to be the best-looking guy on campus. His name was Bill, and he had jet black hair and these beautiful eyes. He was from Decatur, Illinois and was just the nicest guy. After class sometimes we'd get on his motorcycle, which he had built from scratch, and ride around the Ohio farmlands and take pictures. It was so easy and romantic. I thought to myself, “It would be fun to do pictures like this all the time.”

This approach to pictures was very different from going to the couture in Paris! One time, I was in Australia looking for a guy to be in pictures for a story I was doing with Grace Coddington at British Vogue. We met some handsome guys, even in the Outback. Grace jokingly asked, “Bruce, how come I’m always running into handsome guys when I’m with you?” I said, "I don't understand it myself!” We ended up using my assistant in the pictures.

I'll say this much: a lot of the guys I photographed early on were guys you'd want to go on a date with – kind of normal and nice. Jeff Aquilon was serious and sensitive in that way. I like the vulnerability that you discover sometimes in a guy or girl who’s not a model—it helps the pictures.

For me, Robert Mitchum—who I made a documentary about when he was 75 years old—was the sexiest guy I ever met, which shows you where my head is at.

Right: Bruce Weber, “Jeff Aquilon, 9166 Cordell Drive, Hollywood”, 1978, archival pigment print, Courtesy of Galerie Buchholz

Left: Bruce Weber, “Jeff Aquilon, 9166 Cordell Drive, Hollywood, California”, 1978, archival pigment print, Courtesy of Galerie Buchholz

CKE: Did you always have some sort of conversation with people before you ended up booking them? What was the process like?

BW: It’s the same for me now as when I took these pictures at Buchholz: I got to know almost everything about them. I met their parents; I knew where they went to school, and what they wanted to do when they got out of school. They told me about the sports they played and how they felt about their coaches. I'm still friendly with many of them 35-40 years later. I'm photographing some of their grandchildren now, which is kind of crazy.

CKE: How different is to work with people who you know so well versus professional models?

BW: It’s very different, because [professional models] know how to show the clothes if you're taking pictures for a fashion magazine. I don't particularly like when a man or woman wants the clothing to be more important than them in the picture. Editors used to say sometimes, "Bruce, we know you don't like clothes." I would disagree—I just liked the people more.

I was always a little rebellious when working for fashion magazines. I didn't want the girls to wear much makeup. I thought they looked so beautiful, no matter what they were wearing. They didn't mind if I asked them to jump into the ocean in a dress.

I was photographing Kate Moss once, and I said, “Okay, dive into the swimming pool in that dress and a those boots.” I was with Grace again and she went, “Oh no! Bruce, those shoes are so expensive.” I just wanted to have fun like I did with my family on Sunday afternoons. We’d make films and take pictures, and that was my idea of getting along. I used to be quite shy. I think most photographers – or at least the ones that I admire – are shy. I think it's part of being a photographer, because when you have a camera, you're not shy at all.

Left: Bruce Weber, “Jeff Aquilon, Santa Monica Beach, California”, 1978, archival pigment print, installation view Galerie Buchholz, Köln 2025, Courtesy of Galerie Buchholz

Right: Bruce Weber, “Jeff Aquilon. New York, NY”, 1978, gelatin silver print, Courtesy of Galerie Buchholz

CKE: When you were shooting these iconic campaigns for Calvin Klein or Abercrombie & Fitch, why did you choose to show men in that particular way? It was so unique at that time.

BW: For example, at a Calvin sitting, people would say: “Those men and women are so sexy.” I said, “Really?” I didn’t see it like that. I just thought they were extraordinarily explosive people.

I would walk down the street and see somebody and think, “I like this moment in their life. I want to record it.” It’s not like I’m so in love with everyone I photograph. To make a good picture, I have to discover something about them that I admire or relate to or that makes them unique. It could be their hands, or that their feet are too big. It could be a girl who's maybe a little bit heavy but has a sweetness about her that's irresistable.

CKE: Would you say that clothing was secondary for you – even when you were shooting campaigns?

BW: In most cases, I would say yes. There were some important exceptions, like Rei Kawakubo and Azzedine Alaia. I love both of their work. I loved the fact that Azzedine sewed himself, working late into the night. And I loved the women he chose for his show, many of whombecame my friends. An Azzedine show was like having being invited to the best dinner party ever. The clothes were part of it, but it was more about the soul.

Bruce Weber’s exhibition Early Men is on view from June 25– August 16 at Galerie Buchholz in Köln, Germany. Tuesday to Friday, 11AM to 6PM, and Saturday, 11AM to 4PM.

Credits

- Text: Claire Koron Elat