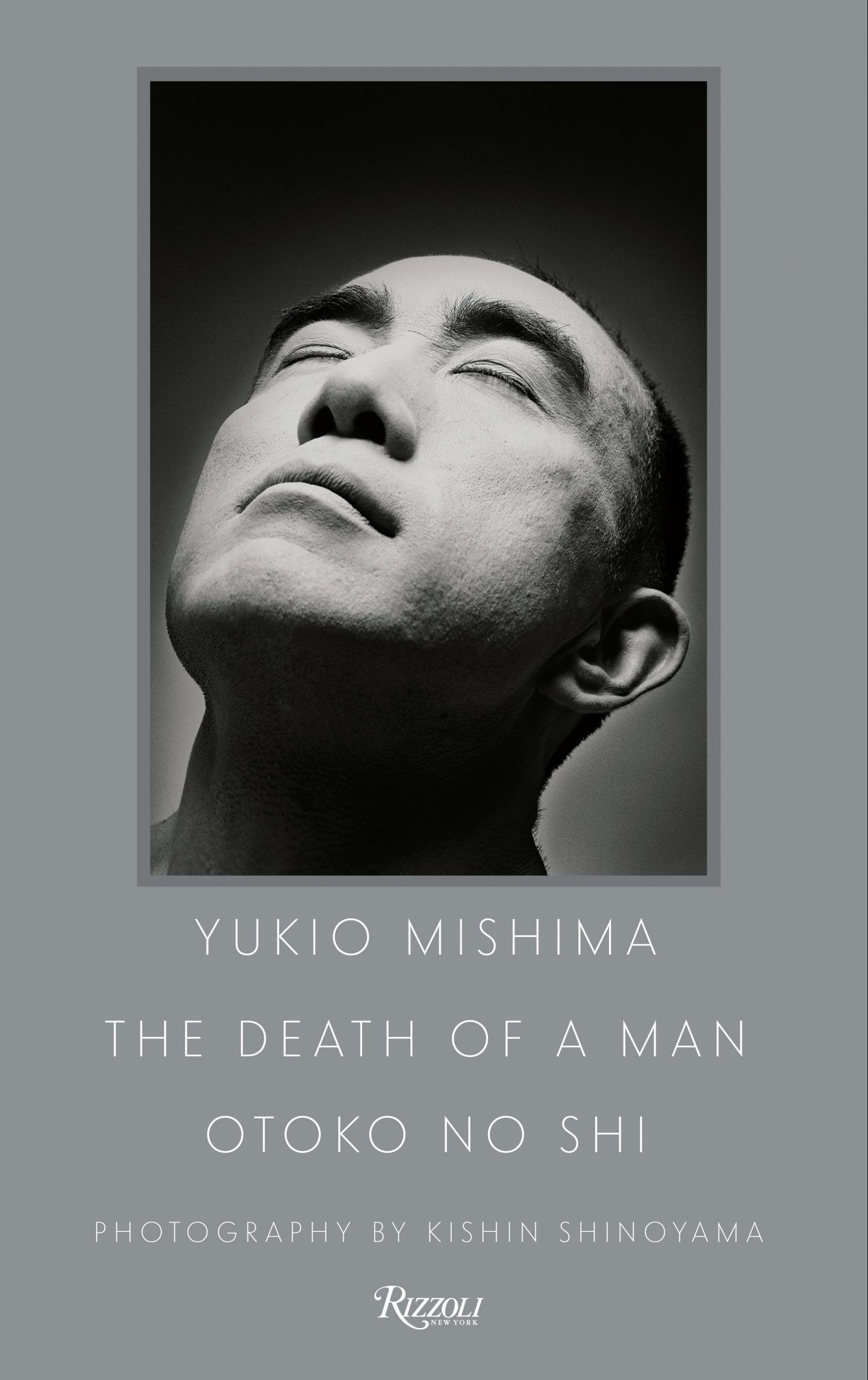

The Death of a Man: YUKIO MISHIMA

|Jasmine Amussen

“I prefer the suicides that are used to establish oneself.”

I have no idea where this is from, but it’s Mishima, obviously. I think it’s in The Temple of the Golden Pavilion.

On November 25, 1970, Yukio Mishima, the Nobel Prize-nominated, body-building, far-right, queer, upsettingly attractive, and insanely prolific author of essays, novels, plays, poetry – the “Ernest Hemingway of Japan” – was jeered away by the Japanese Army he so wished to command and committed seppuku, recruiting his teenaged lover for the final motion of decapitation.

It was messy: apparently it took several strikes to behead Mishima, his thick bull’s neck not lending itself to a clean cut. Mishima never wanted it to be clean, anyway.

As the 50th anniversary of Mishima’s pornographic gesture approached, his work rose again to the surface, in call outs by other authors (see Jeremy O. Harris re: “my favorite writer”), new translations of his books – many of which have not been published in English – and the gorgeous, horrifying Rizzoli monograph The Death of a Man. The fact that the other people involved with the Rizzoli project – photographer Kishin Shinoyama and painter Tadanori Yokoo – managed to keep this collaboration under wraps for almost 50 years is absolutely mind boggling. Mishima’s dangerous and unwieldy legacy in Japan and abroad no doubt helped them keep quiet.

Originally set to be released in 1971, immediately following his suicide, The Death of a Man was a project Mishima wrote, set, and directed himself. Yokoo, a young painter Mishima was very fond of, was supposed to pose alongside the author in a shoot by Shinoyama. In his essay in The Death of a Man, Yokoo says he was hospitalized with a blood clot at the time, and could not make any photographs. Mishima was furious. He kept calling and calling, but it became clear that he had to go it alone. Three days after Mishima’s death, Yokoo was visited by Shinoyama, who showed him the pictures he had made.

“If Mishima had not ended his life in that manner of death, these photographs would have taken on a different significance, but it is impossible to view these images without taking his final act into account. I felt like I was challenged by a Zen koan that demanded, ‘What will you do?’ After Mishima’s all-too-real death, it was no longer possible for me, his surviving alter ego and co-star, to perform my role in Death of a Man so late to the party. I don’t understand why Mishima wanted me as his co-star, but the Japanese ritual of death by suicide requires a ‘fellow traveler’, and perhaps Mishima needed a co-actor to execute his personal artistic creation.”

The role The Death of a Man was supposed to play in the final act of Mishima’s life is quite clear. Much in the way America prepared its citizens for mass (preventable) deaths, for example, of healthcare workers during Covid-19 – calling them “heroes” and other terms of martyrdom – if the publication had come out as planned, it would have been Mishima’s last, poisoned goodbye kiss, a final piece of parting encouragement.

Had The Death of a Man appeared in 1971 instead of 2020, would it have inspired young men towards a similar erotic death impulse? To violence? I can’t say for sure, and I’m certainly not a lost, angry Japanese youth in the aftermath of World War II.

“Perfect purity is possible if you turn your life into a line of poetry written with a splash of blood.”

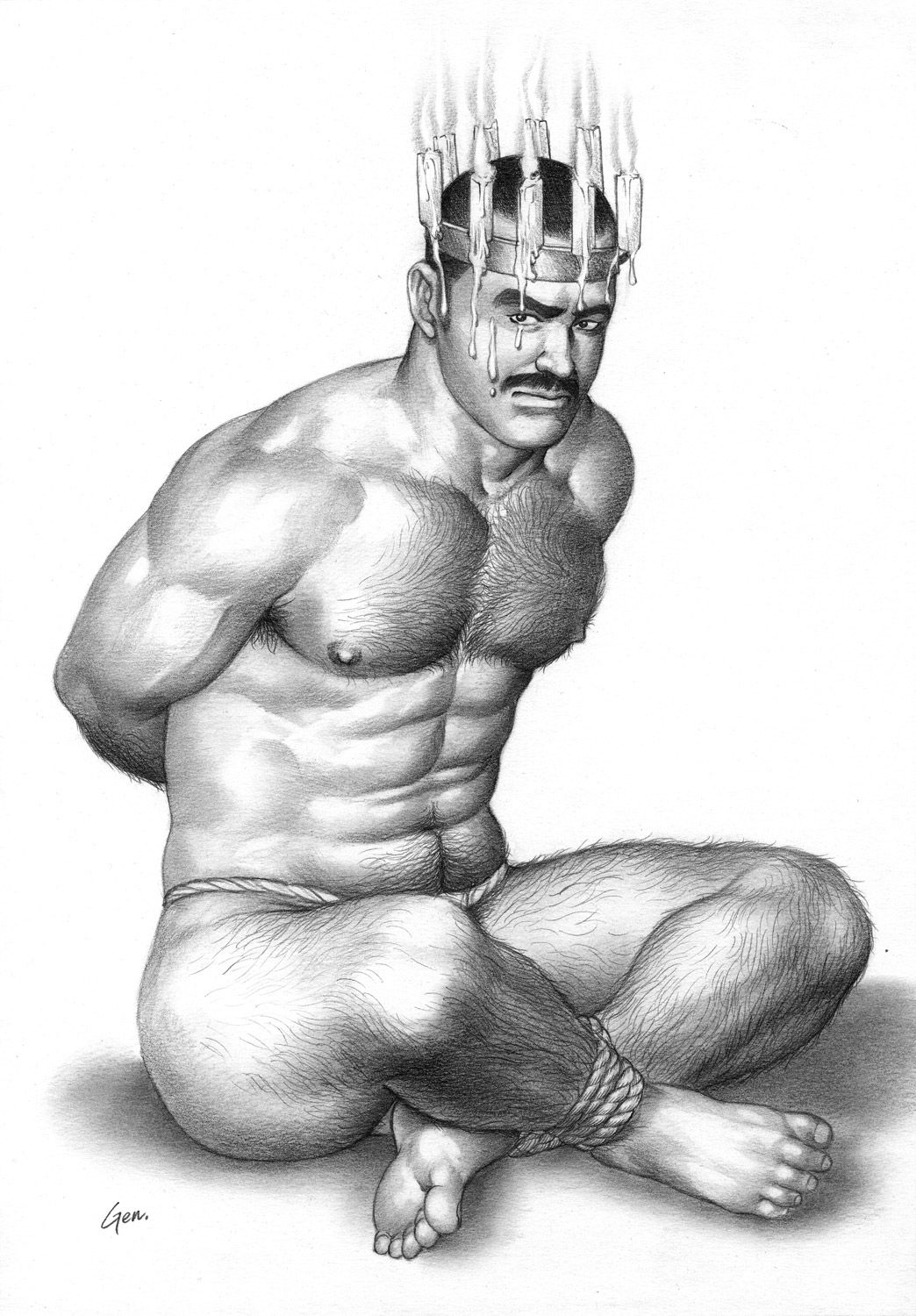

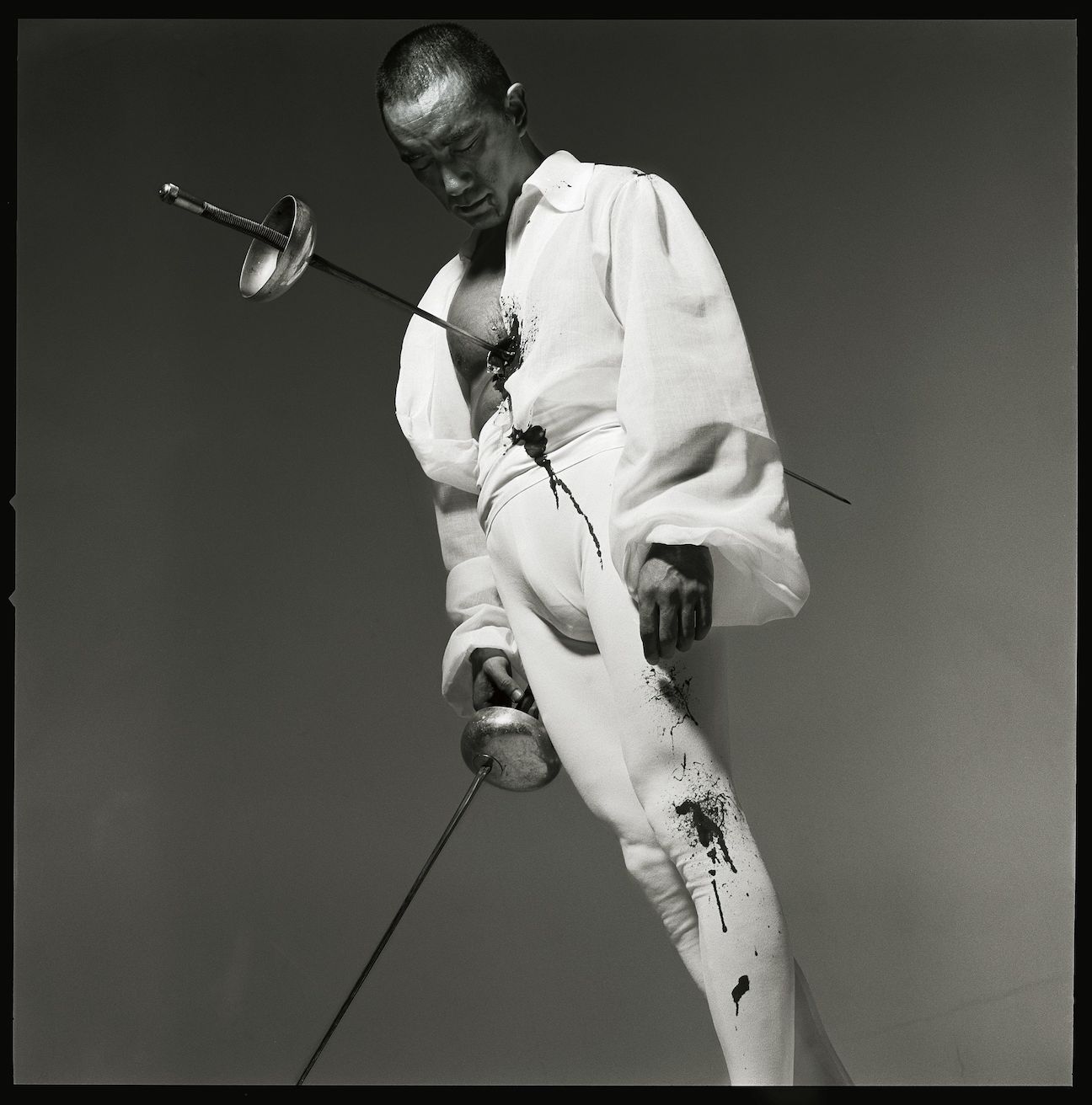

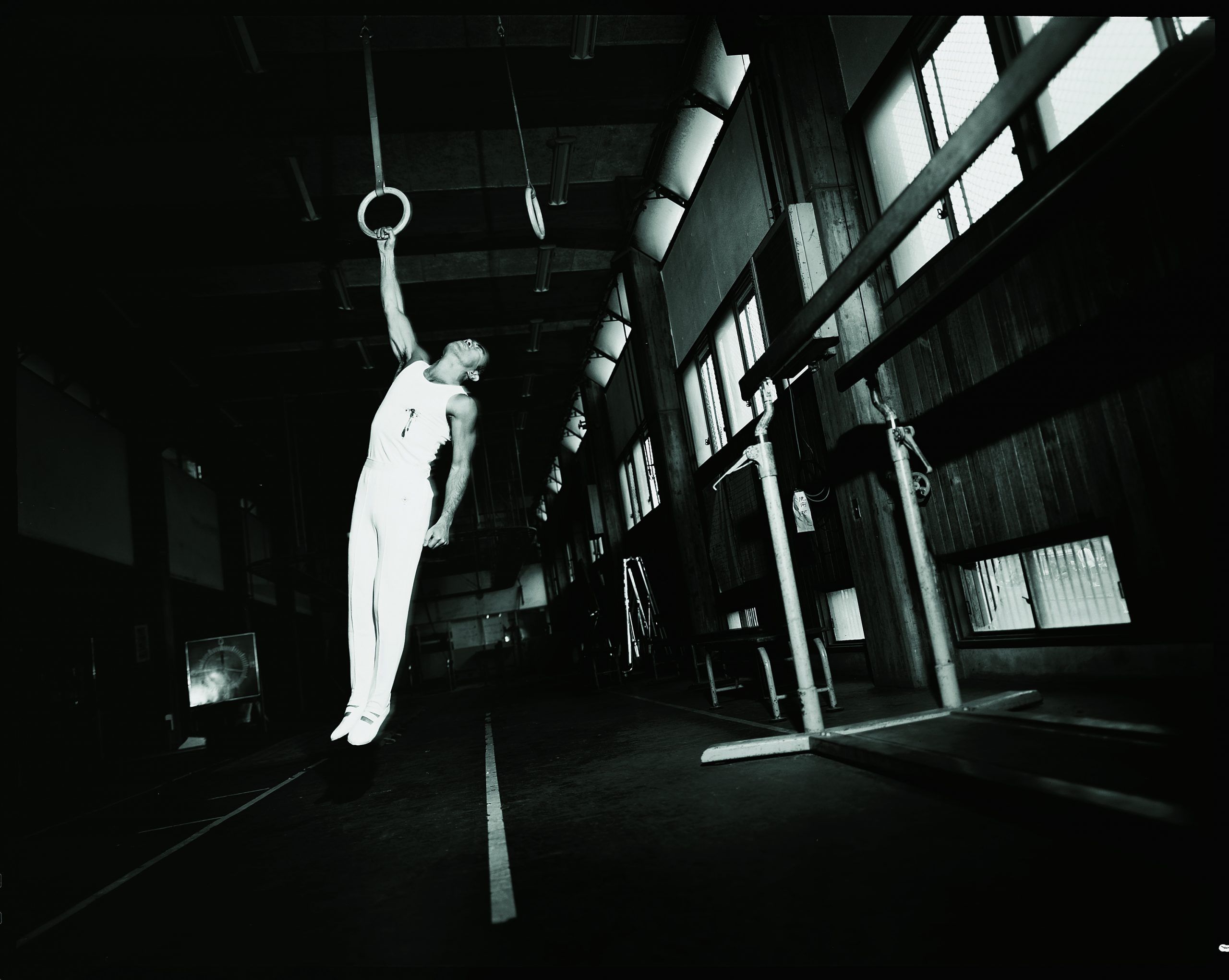

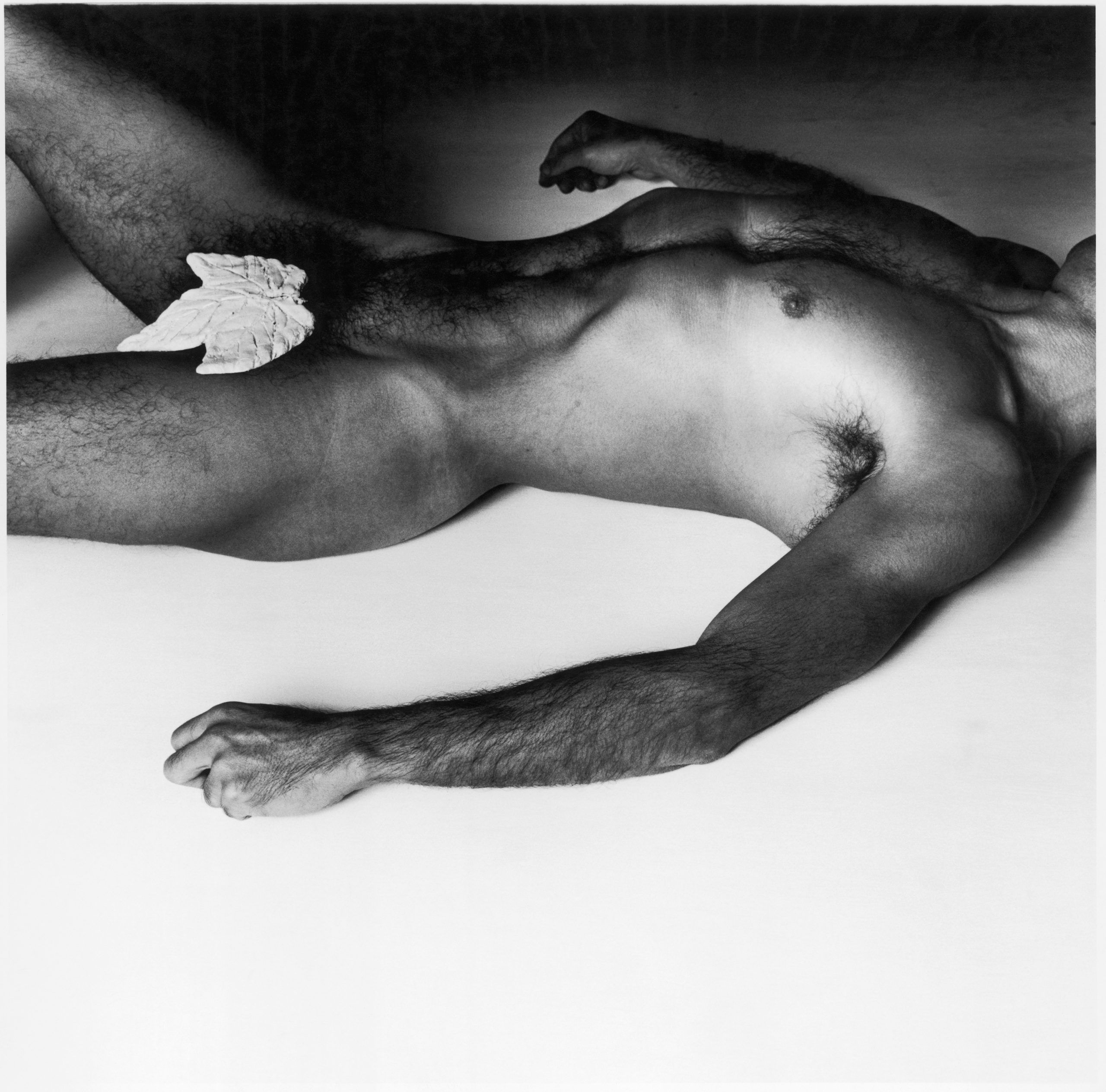

Shockingly sadomasochistic and deeply alluring, the photographs themselves are beautiful and repellent. There is no touch of Shinoyama’s softness, or of the tenderness that accompanied 28 Girls, the work he completed before The Death of a Man. The two projects’ subject matter might be wildly different – the former involved nude girls, the latter nude nationalists – but Mishima always made clear that some of the great defining aspects of the Japanese character he so adored were feminine, neurotic, elegant, and poisonous. Mishima’s own short introductory essay describes the work of his friend Mr. Shinoyama, and one photograph in particular: an image of an eighteen year old girl named Emi Aoki – “of mixed blood,” Mishima so kindly notes – who languidly, elegantly, and fluidly disappears into a bloody sun.

Mishima’s figure does no such thing. All of his staged deaths are filthy, relishing in an orgiastic pleasure of the damned. The Seppuku of a Fishmonger is so slimy and slick with oil that the stomach turns with the page. Trouble at a Construction Site has a bloody axe, and Mishima’s bloody head, and a thrillingly open robe, a dark thatch of pubic hair exposed. His hands are strangely tense, curled inward like claws, as though he doesn’t want to let his pleasure loosen his grip on the reality he has built, or is building.

His flayed A Lynching on Board / The Death of a Sailor is the most overtly homoerotic of the lot; the flagellation marks across his back and his tight white pants could be part of any public scene from the Folsom Street Fair or a dirty magazine bent toward boys with confusing feelings about the man on the cross. While these deaths are supposed to be those of the “everyman,” Yukio Mishima could not look past his own desire to be reborn in blood. Instead he made all deaths heroic in their tragedy, and beautiful in their ecstasy.

Credits

- Text: Jasmine Amussen

- Images: Kishin Shinoyama