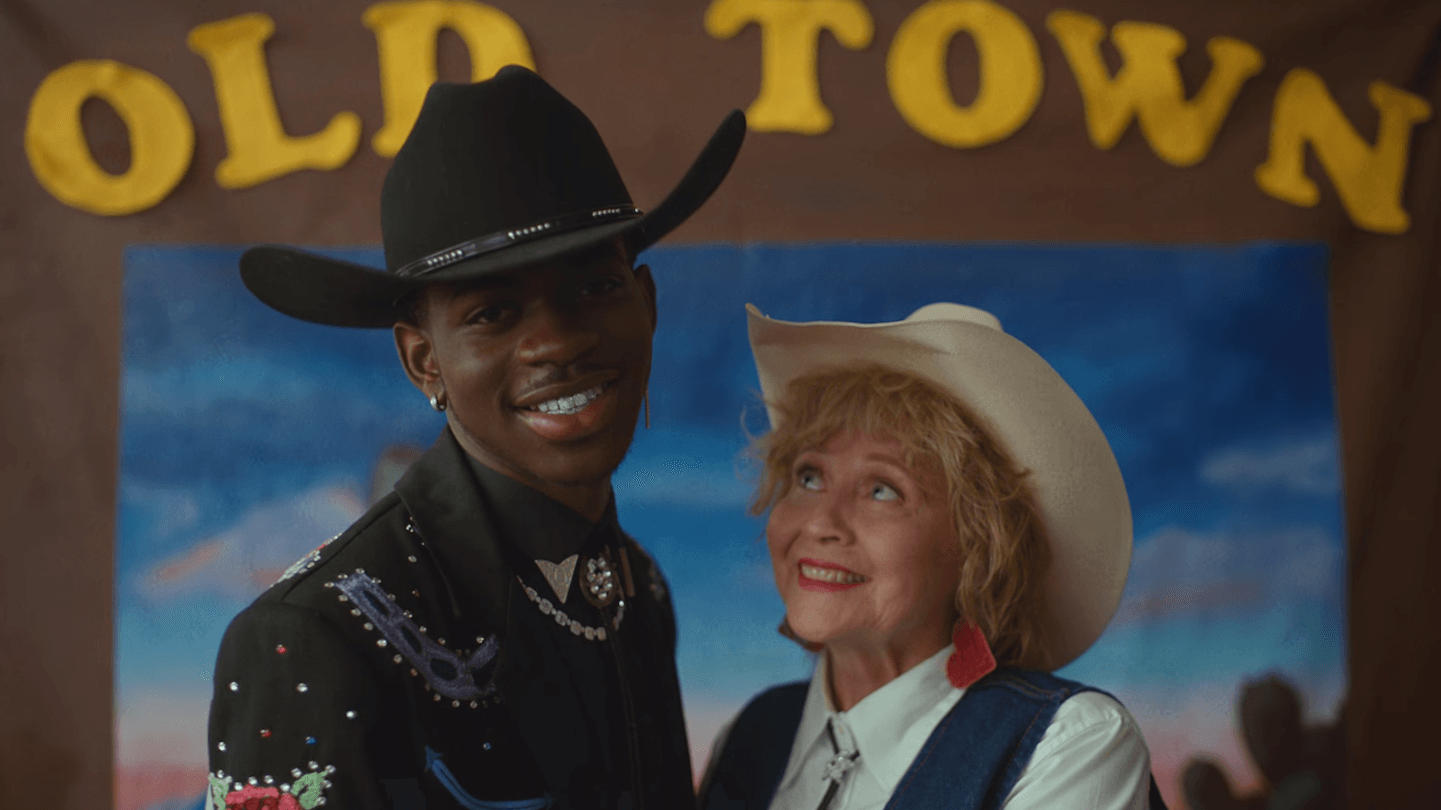

Old Town Fury Road: LIL NAS X, “Daddy Lessons,” and the Black Yeehaw Agenda

|Jasmine Amussen

This morning, Lil Nas X dropped his debut EP, 7 – a much-anticipated follow-up to the rapper’s “Old Town Road,” which started as a viral TikTok hit and wound up spending 11 weeks at No. 1 on the Billboard charts. After a remix with country megastar Billy Ray Cyrus, “Old Town Road” was the most popular song in America, and the center of national debate about what music – and specifically, which musicians – can be considered “country.” In this piece, originally published on the southern arts platform Burnaway, 032c contributor Jasmine Amussen reports on the ascent of the Black Yeehaw Agenda – via Beyoncé, Ray Charles, and Young Thug on a horse – from Lil Nas X’s hometown of Atlanta.

It begins, like many significant cultural moments of the twenty-first century, with someone being rude to Beyoncé. The Houston native released “Daddy Lessons” as the sixth track on her sixth studio album, Lemonade, in April 2016. The country-zydeco song draws on Texas iconography, with lyrics emphasizing the singer’s relationship with her family, whiskey, the Second Amendment, and the Bible, her wariness of men and capacity for self-defense. There is a harmonica, a banjo; clapping hands measure a syncopated rhythm. It is undeniably a country song. “Daddy Lessons” lacks sonic qualities that could place it within any other genre, except perhaps the New Orleans-inspired horn section opening the song. It doesn’t even feature a single electric instrument.

Beyoncé submitted “Daddy Lessons” to the Grammy committee for consideration as a country song, which it refused. The committee reserves the right to say anything or nothing about its methodology. (It’s doubtful committee members would have done themselves any favors by providing details to critics.) But the decision to exclude Beyoncé’s “Daddy Lessons” highlights the racist double standard that arises and the doublespeak that occurs around any music made by a Black artist that isn’t rap. Immediately following the release of Lemonade, country music critics, producers, and artists clamored to announce that Beyoncé couldn’t have possibly made a country song.

“Sure, Beyoncé’s new album Lemonade has a song with some yee-haws, a little harmonica, and mentions of classic vinyl, rifles, and whiskey,” Allison Bonaguro, a writer for Country Music Television (CMT), wrote. “But all of the sudden, everyone’s acting like she’s moved to Nashville and announced that she’s country now. Just because of this song ‘Daddy Lessons.’ It doesn’t sound like a country song to me, she didn’t cut it at a studio in Tennessee, and it certainly wasn’t written by a group of Nashville songwriters.” A few days after this fiercely partisan statement, Texas trio Dixie Chicks covered “Daddy Lessons” live on tour. Months later, Beyoncé performed “Daddy Lessons” with Dixie Chicks at the fiftieth-annual Country Music Awards in Nashville while wearing a sheer, dazzling dress. In hindsight, Beyoncé’s imperiousness is even more shocking than it may have appeared at the time. Less than a week before Donald Trump was chosen to succeed America’s first Black president, Beyoncé entered one of the most conservative and insular environments in the music industry. Allying herself with a group of women who were already despised by the country music establishment—see the 2003 incident in which Dixie Chicks lead singer Natalie Maines told a London audience the band was “ashamed” that then President Bush was from Texas—Beyoncé refused to dress the part, refused to appear humble, and refused to play along. It’s anarchy. It’s chaotic good. It’s absolutely out of bounds. It’s the first superstar moment of the Black Yeehaw Agenda.

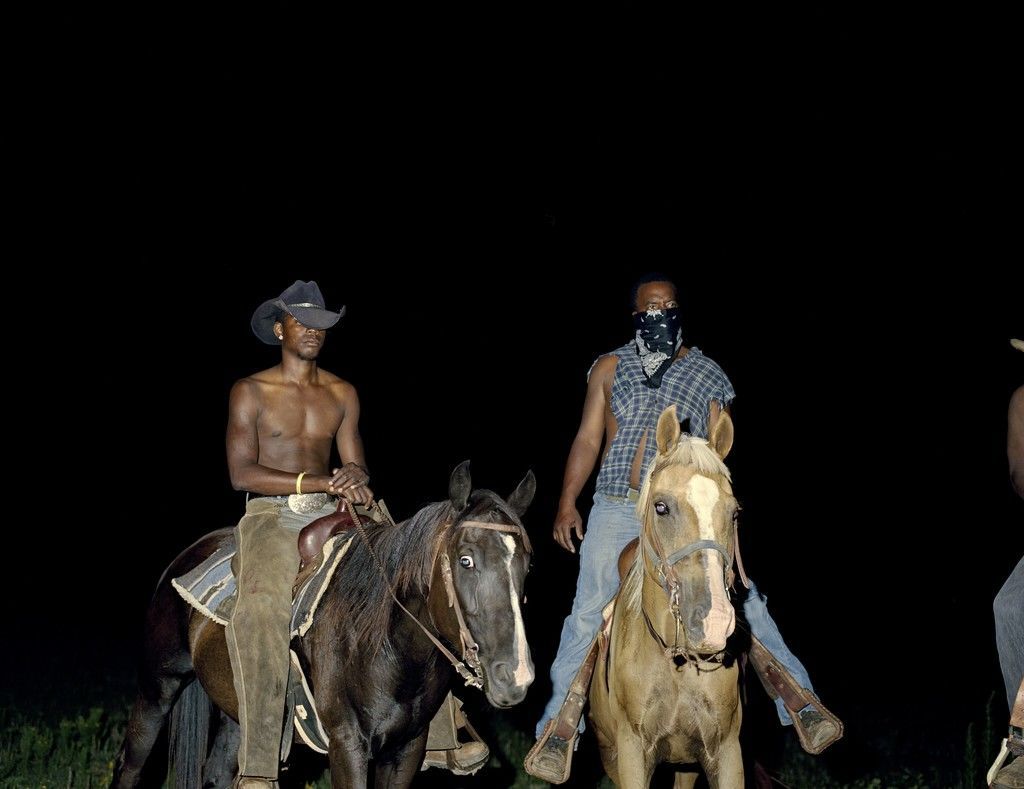

The Black Yeehaw Agenda—which includes everything from Instagram accounts such as @blackgirlsincowboyhats to Young Thug ad-libbing yee-haw —has been percolating for decades but has only recently risen to a full, frothy boil. On a bright spring day in Atlanta a few years ago, I texted my friend while walking down Ponce De Leon Avenue—I think I just saw Young Thug on horse. Young Thug is one of the more difficult to pin down stars of the brilliant, ever-expanding, ever-cannibalizing Atlanta rap constellation. As rappers from around the country continue to make pilgrimages to Atlanta to work with the city’s producers and mixers, hoping to win some portion of the infinitely bankable Dirty South sound, Atlanta has turned inward, looking to its red clay backyard, becoming even stranger, harder, brighter.

Young Thug released the album BEAUTIFUL THUGGER GIRLS in June 2017, delivering what Lil Nas X has called the first country trap song, “Family Don’t Matter.” (The younger rapper has also referred to Thugger, his fellow Atlantan, as a “true inspiration” and a pioneer of the genre.) “Family Don’t Matter” has Thugger morosely considering taking his woman for granted over twangy acoustic guitars, ad-libbing yee-haw as his life falls apart and Millie Go Lightly chides that he keeps living like his family doesn’t matter. Outside of the city and critical acclaim, BEAUTIFUL THUGGER GIRLS didn’t make much of a splash, but there is no doubt that it signaled a wry turn in the way Atlanta rappers positioned themselves in relation to the suburbs, to the rural, to whiteness. Lil Yachty, another Black teen from Metro Atlanta subverting white suburban imagery, has proudly planted his posi-troll flag in the turf of the conservative virtue-signaling brand Nautica—while Republicans have become more openly hostile towards young Black men and Atlanta suburbs have become less Republican. Even as Nautica’s creative designer, Lil Yachty may not have the power to aesthetically neutralize the threat that khakis and polo shirts represented as the white nationalists wearing them marched on Charlottesville and killed Heather Heyer, but the presence of his bubblegum trap persona within the suburban tableau represents a sly cultural infiltration. In 2019, Lil Yachty’s preppiness seems to have more in common with early OutKast aesthetics—the authentic version of “Straight Out of Dunwoody”—and perhaps explains why he has been spared of the vengeful reaction recently faced by Lil Nas X.

The twenty-year-old rapper, who grew up in Atlanta’s Bankhead Courts before moving to suburban Cobb County, released the country trap mega hit “Old Town Road” independently on SoundCloud in early December 2018. The song’s popularity skyrocketed in the following months, largely because of the viral #YeeHawChallenge on video-based social media app TikTok, in which users appear wearing head-to-toe cowboy gear as the bass drops in “Old Town Road.” On March 16, after the its popularity had garnered Lil Nas X a contract with Columbia Records, Billboard—a strangely powerful relic of the days of racist music segregation and tool of bland algorithmic machinations—removed the rapidly ascending song from its country charts. Lil Nas X told Time magazine, “The song is country trap. It’s not one, it’s not the other. It’s both.” Past aural distortion, country and rap music address many of the same topics: cheating partners, money problems, abandonment, violence from the state and lovers, substance abuse, braggadocio—“Old Town Road” contains all of that. The song has plenty of teenage arrogance but also an incredibly clear, singular vision. Lil Nas X is not out to redefine the rural imaginary, he just happens to be doing so on his march to becoming a star who doesn’t have to live in his mom’s house anymore or go to boring classes at the University of West Georgia.

Young Thug can be safely written out or away as a stoned street kid, Lil Yachty can be the token weird Black kid who wants to be on the rowing team, but there is no easy way to dismiss Lil Nas X from where he demands to be. There is no boundary for him. He can move between East Atlanta, Alpharetta, and all the way to Hiawassee because he cannot see a place where he—his music, his ridiculously tall, six-feet-two-inches frame, his diamond grill, his joyful bemusement—does not belong. Can’t nobody tell me nothing, and he’s right.

In a span of roughly six months, Lil Nas X and “Old Town Road” producer YoungKio—two Black teenagers on opposite ends of the planet—created a cultural juggernaut that squarely takes aim at one of the last unmoving myths in America, The Cowboy. The Cowboy is the definitive archetype of American expansionism and manifest destiny—the figure who has conquered non-white peoples, captured natural resources, and herded animals in mythmaking, campaigning, and image-building since Reconstruction. In the white imagination, the cowboy’s whiteness is not only taken for granted but inextricably bound up with his essential exceptionalism and individuality. (Stand your ground is a cowboy mantra.) The Black Yeehaw Agenda is aesthetics, but it’s also action. After almost a century of the weaponization of Black American culture into American soft imperialist power, Black Yeehaw is bringing those chickens home to roost. Instead of Soviet teens screaming for Michael Jackson records and Levi’s, teens from Chicago to New York to Omaha to Mobile are buying Wrangler jeans and cowboy hats—even though John Wayne and the Marlborough Man are long dead.

The power of “Old Town Road” comes from its overwhelming brightness, its undeniability as a country song, its ability to reveal the real or imagined boundaries between the urban and suburban, ex-urban and rural, between generations and eras, and the agency of the players within those bounds. Lil Nas X’s atmospheric rise grants him powers and privileges that were unthought of when Ray Charles recorded his Modern Sounds in Country and Western Music in 1962, so the language used to discuss the rapper is not so much dismissive as it is technical—bigoted America’s preferred contemporary tool for coded racism. The creeping existential crisis that is driving these last-minute genre-defining technicalities is very real. The idea that the Black mecca—Atlanta—produced cowboys is a source of confusion, hostility, and outright resentment from those who would rather not have their genres, identities, or suburban/rural lines muddied, especially by those who are young and not white. “Old Town Road” proposes to expand the archetype of the nation’s favorite and first post-Civil War hero. But critics of the song fail to see that Lil Nas X has, perhaps more successfully than any country star in recent memory, embodied the spirit of the cowboy—a lovable loner whose insistence on being always and wholly himself sets him apart while allowing his horizon to expand to the farthest reaches of the sunset.

The banjo plucks and 808s of “Old Town Road” have nearly drowned out everything else happening in the cultural sphere since March. Taylor Swift, one of the only two non-rappers to make Billboard’s top ten since 2017, released the single “ME!” with the support of the traditional music industry machine in April. A mural showing a butterfly appeared on a street in Nashville in conjunction with the song’s release. “ME!” debuted at number two or three on charts around the world, stuck behind “Old Town Road.” The only person who could truly interrupt the song’s cultural dominance was the Diva Imperator herself, Beyoncé. On April 17—perfectly timed for Black Spring Break, for Founders Day at Spelman, for the most beautiful spring weeks in Atlanta—Beyoncé released the live album of her 2018 Coachella performance and the accompanying Netflix documentary. Called Homecoming, the meticulously coordinated performance represents the fulfillment of the imperial vision for Black culture the singer first signaled with her November 2016 appearance in Nashville. Ignoring the usual Coachella flower crowns, Beyoncé’s mammoth ensemble enacted nothing less than a two-hour exaltation in explicit, precise aural and visual terms. The performance marked the first year in the festival’s history that did not feature a rock headliner. Homecoming brought the collective Black American experience—a shared history whose traditions are rooted in the South—across the vast frontier to a blockbuster music festival on the far edge of the West. While Homecoming does not yee-haw like “Old Town Road,” it presents Beyoncé as The Cowgirl, refusing to operate within the bounds set by traditional festival experiences, refusing to accept the fact that her culture was unwelcome at Coachella, and boldly planting her lemon-yellow flag in the desert, proclaiming this as one for Black history.

No one has any idea what the future holds for Lil Nas X—his entire story is unprecedented and uncharted—but his infectious yeehaw sunshine has already done its work. Shortly after the “official movie” for “Old Town Road” was released in May, Wrangler launched its Lil Nas X capsule collaboration featuring boot-cut jeans and cut-off shorts that—true to the song’s lyrics—bear Wrangler on the booty. The brand’s social media pages are rife with comments such as, “Wranglers are to be worn by cowboys and farmers, not rappers” and “[‘Old Town Road’] is ruining the cowboy name that y’all have,” alongside threats to boycott the brand, videos of white people burning Wrangler jeans, and angry call-ins to talk radio with thinly veiled (or not) racist tirades about a Black teenager wearing a certain brand of pants. Lil Nas X himself thought it was all a bit much, tweeting “y’all really boycotting wrangler? Is it that deep?” The collection has been sold out for weeks.

Beyoncé’s future we can see a bit more clearly. Smiling from her giant pyramid in the California desert, she thanked Coachella with a question. “Thank you for allowing me to be the first Black woman to headline Coachella. Ain’t that a bitch?” The next time we see Beyoncé, I don’t know where she will be, nor where I will be, nor any of the others working under the Black Yeehaw Agenda. But among the inhabitants of earth, who can hold back their hands or ask of them, “What have you done?”

Yee-haw, y’all.

Credits

- Text: Jasmine Amussen