Of Cats and a Unimog: STANLEY KUBRICK and his Driver, EMILIO D’ALESSANDRO

The story of STANLEY KUBRICK and his driver EMILIO D’ALESSANDRO is more than that of an undeniably genius, famously obsessive film director and his loyal employee. It is a story of love between two straight men that spanned 28 years before it was cut short by the director’s death in 1999.

I. MENTMORE TOWERS

Someone driving around the English countryside near Mentmore on a cold Saturday night in the late 90s might have encountered a tableau as eerie as it was bizarre and affecting. Approaching the dramatically lit, turreted Victorian manor that was built for a Rothschild, a car stood still, moved forward a few meters, and then stopped again. A bearded, disheveled-looking man in his 60s or 70s, shabbily dressed in a multi-pocketed, MacGyveresque fatigue jacket and running shoes, trailed behind it on foot, taking pictures of the barely changing scene.

The bearded man was none other than Stanley Kubrick, and he was here doing light studies for Eyes Wide Shut (1999), his erotic-nightmare adaptation of Arthur Schnitzler’s Traumnovelle (1926) starring Tom Cruise and Nicole Kidman. The director was snapping a picture every minute to figure out the best conditions to shoot the sequence he had in mind – Cruise’s character arrives at a secret, masked party that’s equal parts orgiastic bacchanal and occult ritualistic sacrifice. A task most directors would delegate to underlings after reaching a certain status and age, it had to be done in person, and it had to be done by the exacting, Bronx-born auteur of 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968) himself.

The man in the car, meanwhile, who would hit the gas and back up as his friend beckoned, was Emilio D’Alessandro, Kubrick’s driver, courier, secretary, estate manager, and indispensable middle-man to the world. As that night’s adventure reveals, theirs was an unusual friendship, a complicity based on an almost pathologically obsessive work ethic and shared dedication to doing things until they were just so – no matter how much time or how many tries it took.

But the two men’s story is more than that of an undeniably genius, famously obsessive film director and his loyal, intellectually diverse employee. It is a story of love – affection, dependency, and other corollaries of the term included – between two straight men that spanned 28 years before it was cut short by the director’s death in 1999. It was during these years that Kubrick completed A Clockwork Orange, Barry Lyndon, The Shining, and Full Metal Jacket, arguably the centerpieces of his revered legacy.

Today, Emilio lives in Cassino, an hour and a half southeast of Rome, with his English-born wife, Janette, whom he married in 1962. Speaking in the farmhouse that used to belong to his father, Emilio wistfully recalls the evening at Mentmore close to 20 years ago:

“It was so cold, and he was outside taking pictures of me inside of the car driving up and down the drive with the headlights on.”

Emilio’s boss did not look well at all. It was obvious Kubrick didn’t feel well, but he didn’t think he had gotten sufficient light tests and wanted – as always – to keep going. When Emilio asked the director if he was feeling alright, Kubrick replied he was fine.

“No, you’re not,” replied Emilio. “Give me the camera and get back into the car. We’re going back home.” Emilio’s hunches that night proved correct. Kubrick died not long after, having barely finished editing Eyes Wide Shut and just a few days after screening what is believed to be a final cut to friends and family.

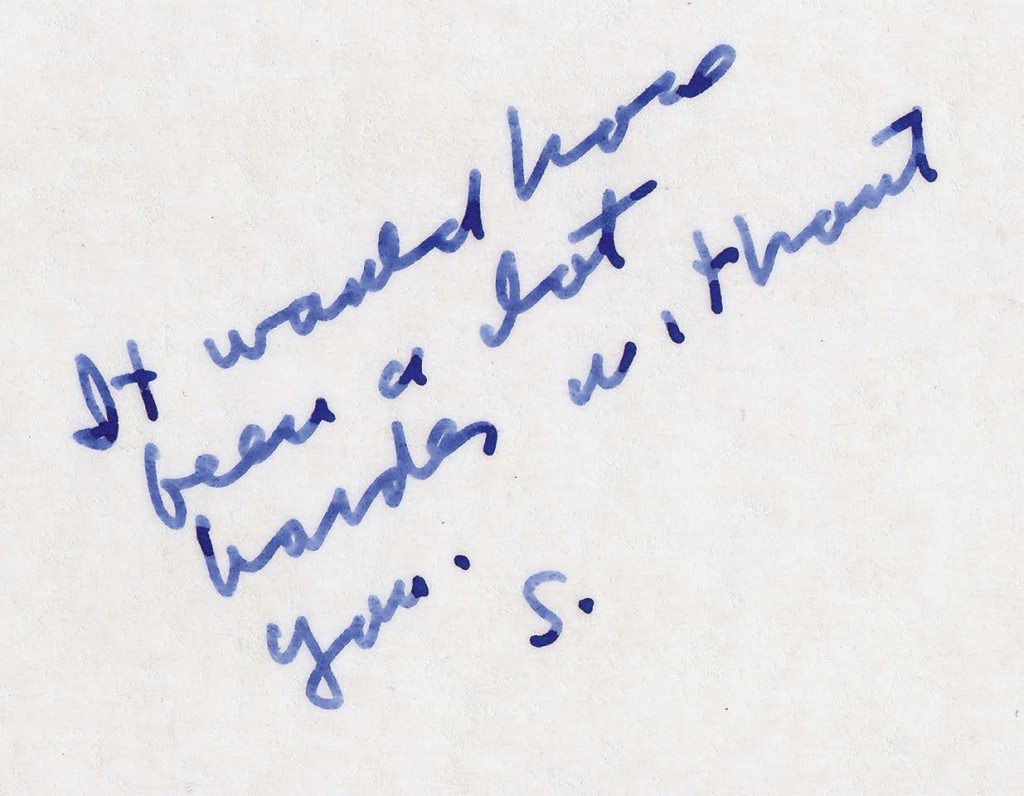

The director Alex Infascelli, who is currently working on a documentary about Emilio’s life, titled S Is for Stanley, says it is hard to overstate “how much Emilio meant for Stanley to be Stanley Kubrick. There would have been a Kubrick of course, but it would have been a different Kubrick.”

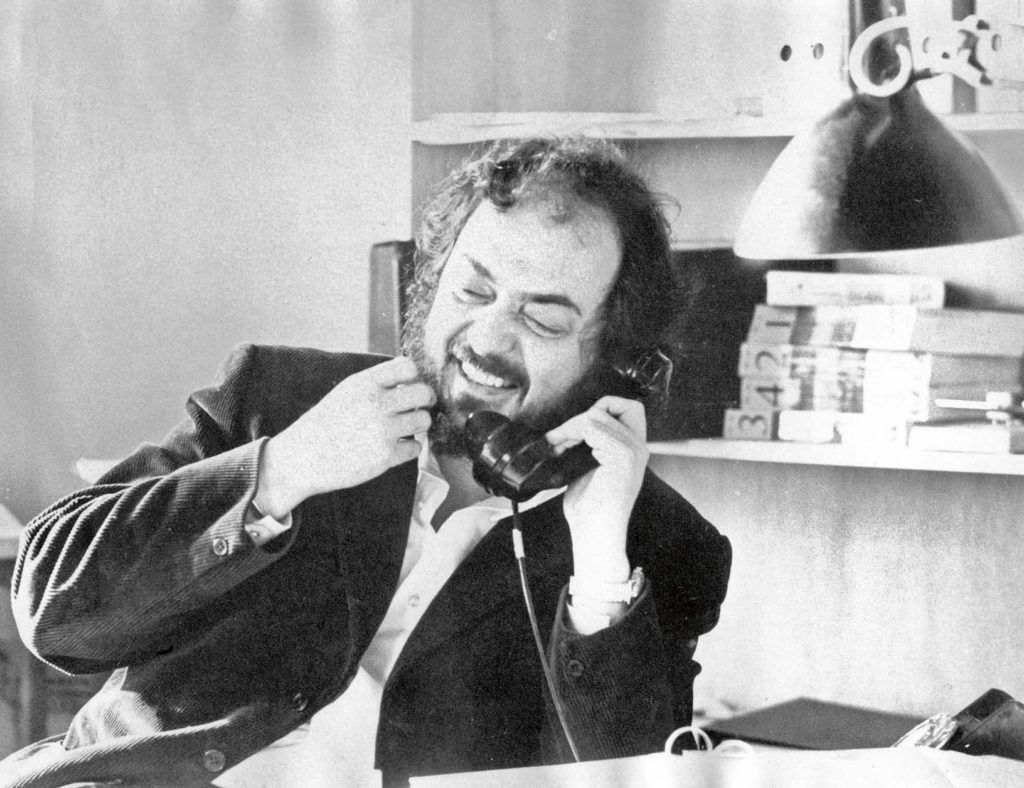

The allegedly reclusive director was, in fact, more social than is widely believed; he relied mostly on long phone conversations to stay in regular contact with a number of close collaborators and friends. But it is true that Kubrick’s delicately calibrated filmmaking machine would have been a lot less efficient, and that he himself would have had a lot more trouble dealing with the outside world, had it not been for Emilio, his most trusted companion and foot soldier. Besides cleaning, driving his cars, and running every conceivable production, household, and personal errand for his boss – tasks that ranged from the banal to outlandish – Emilio was the director’s most vital liaison with wider humankind, and that includes his daughters.

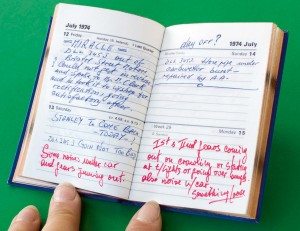

Among the more fascinating documents Emilio keeps in drawers and folders full of Kubrick photographs and notes are several memos – some handwritten, others typed – outlining precise rules, instructions, and things to watch out for when interacting with his daughters, including Vivian, who eventually found a refuge from her oppressively close relationship with her father in Scientology.

In a particularly enigmatic missive, Kubrick instructs Emilio to “make sure [Vivian] gives you the airline, time of departure, destination, and flight number for her trip,” adding that his daughter would probably prevaricate when asked to provide this information. Kubrick adds to not “let her get away with it” or “see this note.” Of the difficult fatherdaughter relationship, Emilio says in the upcoming documentary, “I had to be between them.”

But that’s only the tip of the family-life iceberg. There are innumerable papers in Emilio’s possession that detail things like the precise type, color, and quality of toilet paper that needed to be placed in the apartment for the actors in The Shining (1980), as well as where the replacement rolls were to be placed. Everything had to be personally approved by the detail-obsessed director. If the humble – but never submissive – Italian driver won the distrustful director’s confidence, it was because he followed all directions to the letter without questioning them – even if that meant spending months building a perfect fence intended to safeguard Kubrick’s beloved cats.

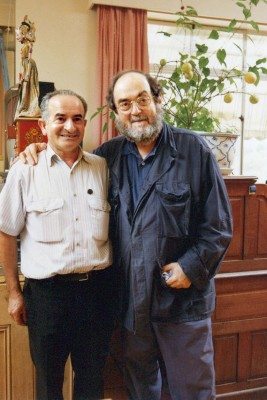

Emilio recalls how, when he first met Kubrick, he thought he “looked like Fidel Castro”

It was not unusual for the painstakingly precise directives and rules Emilio received to concern animals. Emilio’s initial job training included a seminar on the do’s and don’ts of the director’s cats and dogs, along with the warning that following the rules about the animals was probably the most important thing to remember at Abbots Mead, the Kubricks’ north London home and a self-contained film factory of sorts. (When he settled in England, Kubrick set up his life so that his family and work were one; at Abbots Mead, and later at Childwickbury Manor, the director wrote, researched, edited, and managed production details, thus retaining almost complete artistic control while being financed by Warner Brothers, a rare exception in the history of filmmaking.)

With the director’s love for animals verging on the absurd, Emilio was required to be present whenever one of his prized pets had to be medically examined. And so, when Victoria, one of the director’s favorite cats, fell ill in 1996, Kubrick had Emilio drive her to Cambridge. (The feline specialists at the renowned university handled all Kubrick cats, as the director would not entrust his animals’ care to any ordinary local veterinarian.) With instructions to photograph the cat every few minutes in order to monitor her recovery, Kubrick also gave Emilio a camera to take with him, and the result is a series of slightly blurry, barely distinguishable cat shots worthy of Gerhard Richter.

II. THE ROCKING MACHINE

It all started with a porcelain penis. Emilio D’Alessandro had left Italy at age 18 in order to avoid military service. The son of poor farmers from a small village in the Cassino region, an area known for one of the bloodiest battles of World War II, as a young child Emilio had seen fields littered with corpses of young Allied and German soldiers, leaving an indelible impression in his mind and inspiring his resolution to never engage in any kind of military activity.

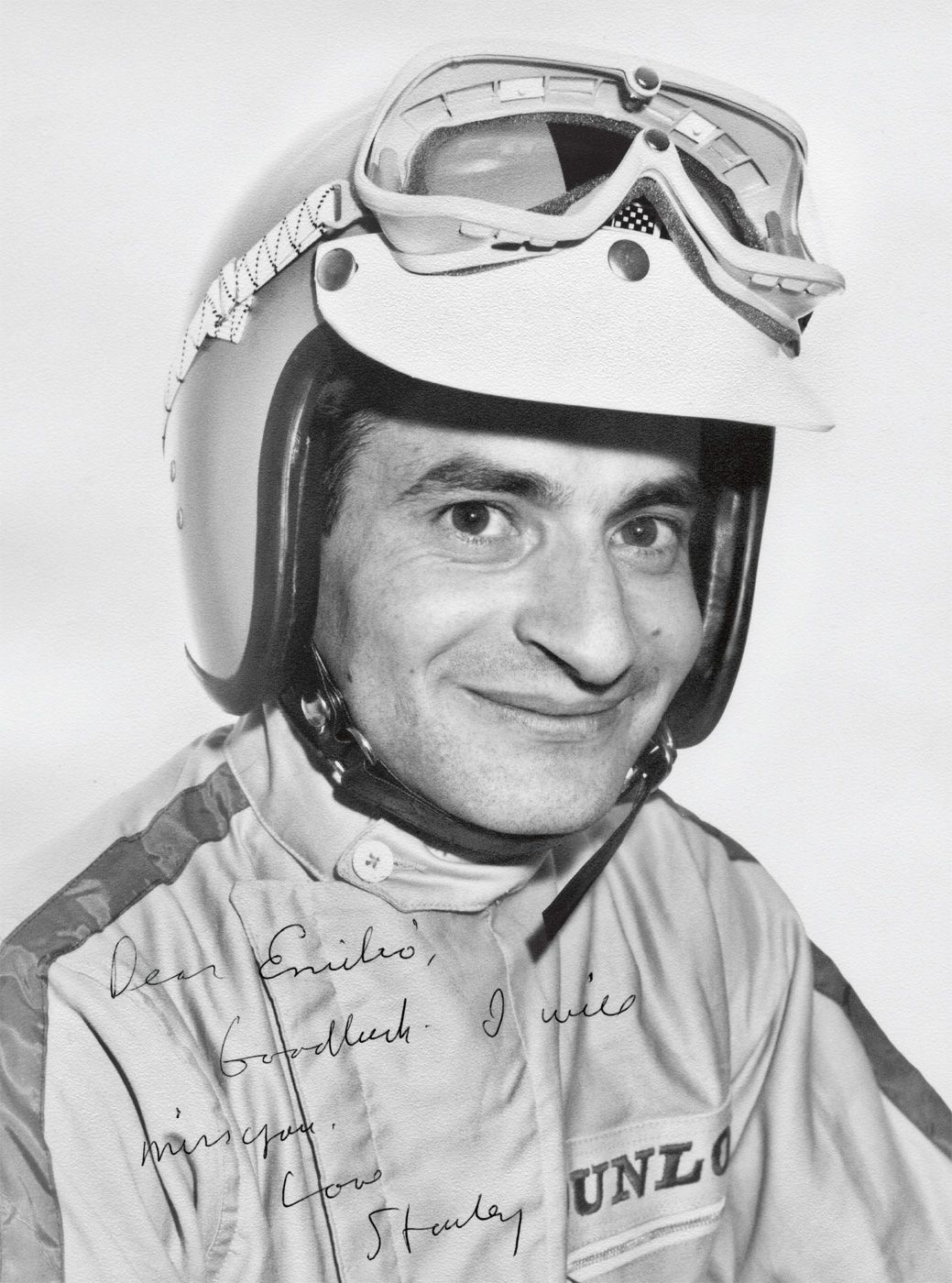

In 1960, Emilio embarked on a three-day train trip to London. Once in Britain, the resourceful illegal immigrant soon obtained papers and began to work his way through a series of odd jobs, including one at a hosiery factory and another working as a mechanic near the famous race circuit Brands Hatch. It was working on cars that ignited Emilio’s first great passion: racing. Following a need for speed, freedom, and control over his life, Emilio soon started training to become a race car driver.

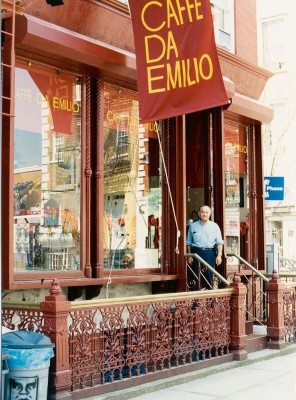

But personal dreams aside, Emilio was now also a husband and father of two young children – Marisa and John – whom he needed to support. After a few difficult years during the crisis in Britain, Emilio’s economic salvation and fate-changing job came through a minicab company in an area north of London that was home to several film studios.

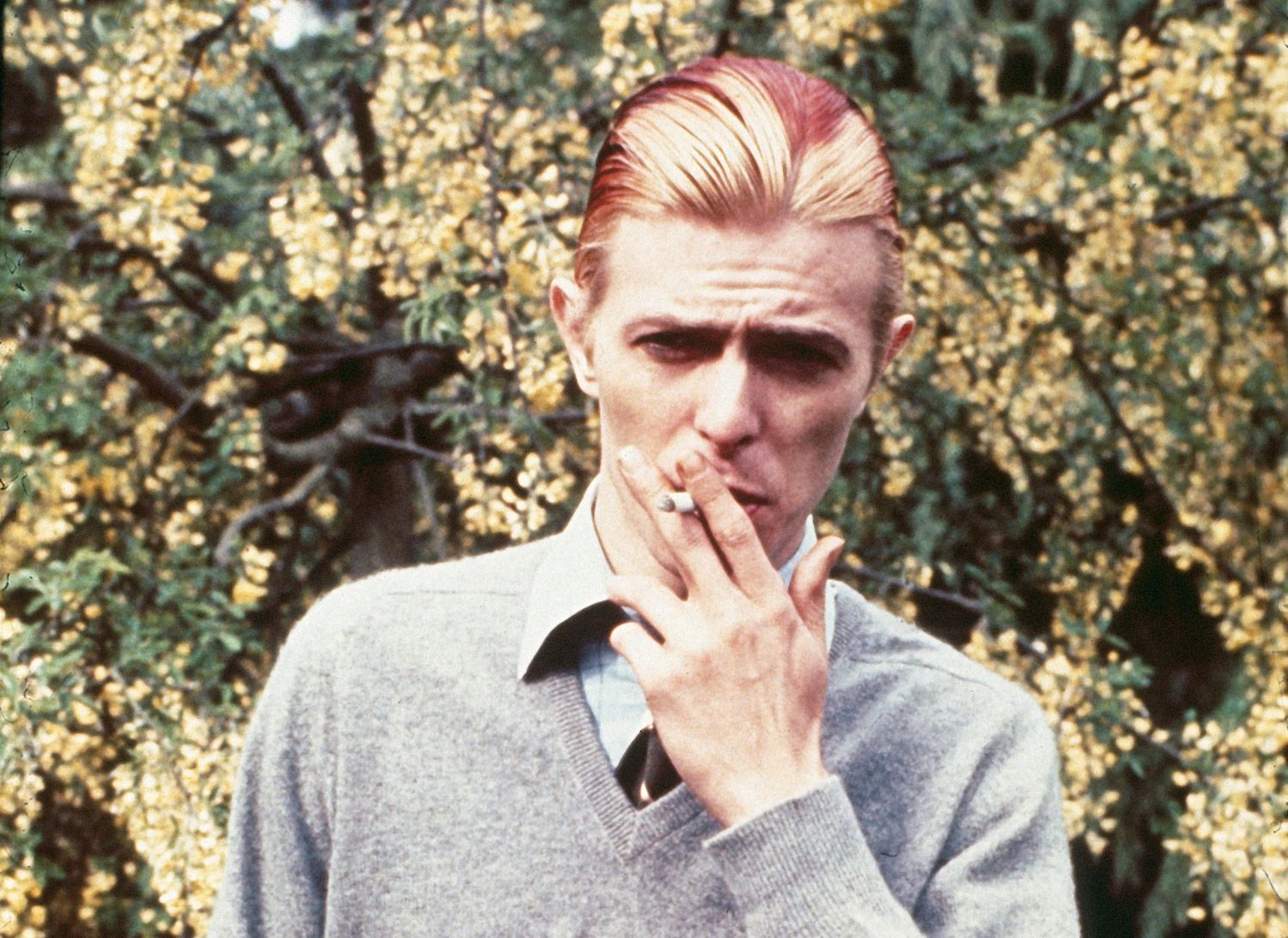

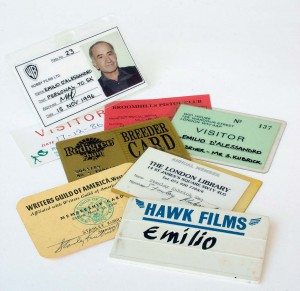

One night, near the end of 1970, he was assigned to deliver a gigantic rocking phallus, a prop for A Clockwork Orange, from a film studio in Borehamwood to another location. Having delivered the porcelain cock intact and on time (punctuality mattered a great deal to Kubrick), Emilio was soon hired to work exclusively for Hawk Films, the director’s production company. In the memoir he cowrote with Filippo Ulivieri, Emilio recalls how, when he first saw Kubrick, he thought he “looked like Fidel Castro.” Although the director was already famous by then, when they met in 1971 Emilio had never heard of him.

It was the Italian farmer’s son’s obliviousness to his employer’s fame, his infallible work ethic, and expertise with cars that quickly earned him Kubrick’s trust. Meanwhile, it seems that to Emilio, working for the demanding, idiosyncratic filmmaker proved to be a good substitute for the adrenaline rush of driving a car at over 100 miles per hour. Before too long, Emilio was doing everything for Kubrick: driving important actors to meet him, taking his daughters to school, checking the dailies in the morning and bringing them to the lab, maintaining all of Kubrick’s cars, taking care of the director’s cats and dogs. He was also the only person, besides Kubrick’s wife, Christiane, who had access to the director’s private rooms, known to be “sacred and inviolable” among his staff. Emilio spent more time with Kubrick, or doing things for Kubrick, than with his own wife.

III. CAUTION, MAINTENANCE, AND DILIGENCE

If cats and other four-legged creatures unwittingly tested the limits of Emilio’s rapport with his boss, it was four-wheeled vehicles that propelled the relationship forward. Through cars, and time spent inside of cars, Kubrick learned to appreciate, trust, and depend on his new employee. Ever an astute observer of people’s qualities and flaws, the director noticed several things about Emilio beginning with their first encounter that soon made the man from Cassino indispensable to him.

For one, the trained race car driver was willing to work around the clock. In one of their early, deceivingly casual conversations – the verbal questionnaire was already part of Kubrick’s methodical vetting process – the director asserted his disregard for the English 40-hour work week, which struck him as utter rubbish. “It’s a waste of time to stop work at six. There’s still half a day to make use of,” he declared. ”I need you to be there when I need you, even if that means in the evening, after dinner.” Emilio, needing the money, was game.

For another, it’s easy to overlook how fundamental Emilio’s driving skills were to the lasting, resilient bond between the two men. While stories that Kubrick wouldn’t let anybody driving him go faster than 35 miles per hour and would not get in a car without a helmet seem exaggerated, the filmmaker did display an obsessive preoccupation with car accidents – and accidents of any kind, for that matter.

From nutritional ticks to his refusal to fly, Kubrick went to great, neurotic lengths to preempt any kind of harm to his person – protecting his body meant protecting his brain and thus his artistic vision. In light of such a fixation on safety, the fact that one of the first questions the director asked his new driver was why he drove so carefully seems hardly incidental. (Emilio responded that he learned to drive fast but safely on the race track.)

Just because you’ve known a few control freaks in your life doesn’t mean you can imagine what Stanley Kubrick was like

. Kubrick was not simply impressed that a Formula Ford driver could steer the car so well; it made perfect sense, and became a logical necessity to him – in the same way that it made sense and was a natural requisite that all of his cats be treated at Cambridge when they got sick – to be chauffeured by someone trained to protect his own life in extreme conditions.

Lastly, there was the day the director suggested they take Emilio’s car rather than his own, more comfortable limousine. Once inside the vehicle – a Hillman Minx – Kubrick went silent, impressed by its spotless interior. Finally, he said, “It looks new. It’s in better condition than mine. My vehicle isn’t this clean even when it comes back from the carwash. Do you look after it yourself?”

Once again, this wasn’t a casual inquiry. The director’s mind was made up: this was one man who had to work for him, no matter what. Back at Abbots Mead, Emilio’s principal duty was henceforth established. “Could you clean them all?” Kubrick asked, referring to his collection of cars. “I’d like them to be like yours.”

“But you only need to clean the inside of the Mercedes,” he added. The Mercedes was special.

IV. ONE IN EVERY COLOR

Apart from the ominous arrival at Mentmore Towers – which is supposed to be an estate on Long Island – there is another mysterious, dreamlike scene in Eyes Wide Shut involving a car late at night. In it, a young blonde boy shoves Cruise’s aimless, adrift character off the street curb, and he falls onto a blue Mercedes-Benz.

Much has been written about the importance of color in Kubrick’s films, including in this brief vignette – blue is never just blue, and red is never just red. Some of it may well be true. But the choice of car here speaks as much to Kubrick’s real-life passions as to whatever the director may have been trying to say about human nature via this or that hue.

Kubrick’s love affair with Mercedes-Benz began in the late 50s while he was filming Paths of Glory in Germany. He bought a small black model from the company known for its silver, three-pointed star, the first in a series of high-end German cars – and of several by the Stuttgart-based maker – the director would own over the next three decades.

According to Emilio, Kubrick thought Mercedes was the perfect car: powerful yet quiet, spacious inside without being too big on the outside. For the pathologically safetyand perfection-oriented director, the fact that, in the 70s and 80s, Mercedes had a reputation for making the world’s safest and most reliable cars was surely another consideration.

But if Emilio was the person who came in closest contact with Kubrick’s motorized fleet, he isn’t the only one who fondly remembers being inside of the director’s trophy cars. In fact, many a screenwriter and actor has singled out being driven by the Italian driver in a German car as an essential element of a Kubrick collaboration. Emilio put a face and soul to this obligatory component of working with the master.

Even the director’s obituary for the New York Review of Books, written by co-author of the screenplay for The Shining Diane Johnson, mentions a multitude of cars in a multitude of colors. “The experience of all of Kubrick’s writers has been remarkably similar – driving in his car to the isolated estate, the daily work with a charming and interesting, if demanding, companion. The cars changed – a copper-colored Mercedes stretch when I was there – but Emilio stayed.” It isn’t clear which car Johnson remembers – at the time there was a gold 450 SEL, notable for having been crashed into the house by the director and for being the cats’ favored mode of transportation, and a red 350 SE, used for production purposes during the making of the iconic horror film.

Before these models came into the picture, Emilio drove and cared for the director’s famous “White Mercedes,” a 280 SEL, arguably the flagship of Kubrick’s serial motorcade. Ryan O’Neal, the lead in Barry Lyndon (1975), loved this car so much that Kubrick became concerned the actor wanted to steal both it and his driver. (The director then offered O’Neal his own pairing.) Another Kubrick collaborator, science-fiction writer Ian Watson, who published his memories of working with the director in Playboy magazine, reveals that the last Mercedes replacement had to do as much with the filmmaker’s McDonald’s binges as with his genuine passion for automobiles.

According to Watson, the filming of The Shining overlapped with a temporary obsession with Big Macs. One day after finishing another double-decker hamburger, the director threw the crumpled wrapper out through the open sunroof, only to have the garbage promptly returned in his face. “Fuck, this car isn’t much good,” Kubrick exclaimed. Clearly, it was time for a new Mercedes. Sure enough, soon afterwards Kubrick purchased the charcoal 500 SEL that remained among his favorite possessions from when he bought it in 1985 until his death. It was Emilio, of course, who made the pilgrimage to the dealership for servicing every year.

V. A YELLOW SUBMARINE

Emilio finished winning his employer’s heart when he turned out be the only person Kubrick knew who could drive his adored yellow Unimog, a four-wheel-drive truck manufactured by Mercedes-Benz that the director had bought from a farmer while filming Barry Lyndon. Until Emilio came along, it had been sitting idle in a garage because nobody had the skills to drive it. When he first heard the vehicle’s sixteen-gear engine, Emilio thought it sounded “like a machine gun”; when he first saw the thing, it reminded him of a “yellow submarine.” But he soon had the unwieldy truck under his control, which made Kubrick clap his hands in a rare burst of excitement.

Working for Kubrick wasn’t all fun and games, however; devoting one’s life to a filmmaker known for his dogged determination to have things his way came at a high price. As Michael Herr, a friend of Kubrick’s who co-wrote the screenplay of Full Metal Jacket (1987), wrote in Vanity Fair in 1999, “You’d have to be Herman Melville to transmit the full strength of Stanley’s will. Just because you’ve known a few control freaks in your time [doesn’t mean] you can imagine what Stanley Kubrick was like.”

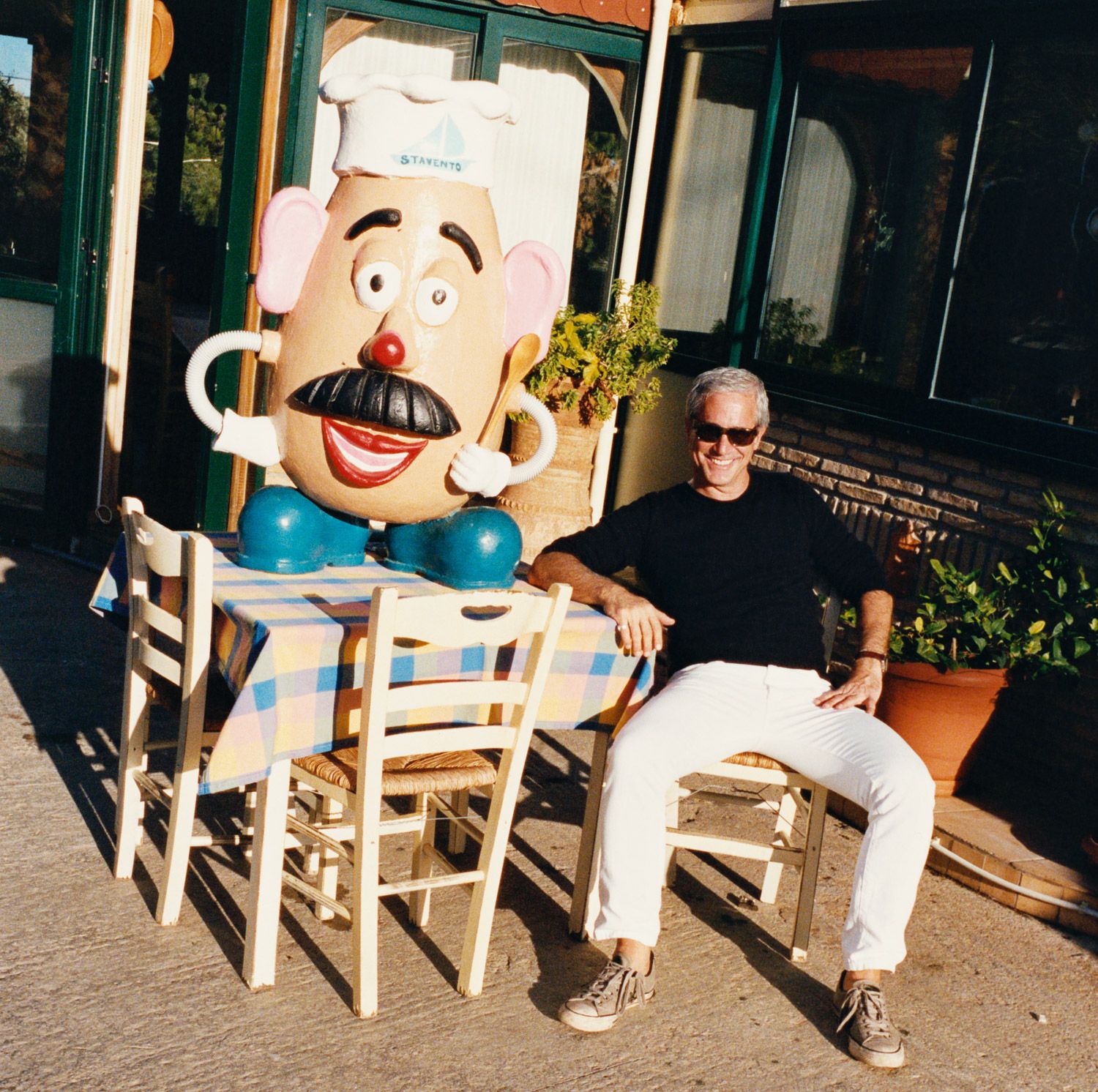

Or as Watson, who befriended Emilio, put it, “When you’re invaluable to Stanley, it’s difficult to escape or to have a life.” Emilio knew this and tried to get away from Kubrick’s inexorable demands for a long time. Finally, in 1994, after having been absent when his father died, Emilio and Janette left for Italy with the intention to stay there. The separation lasted two years.

In 1996, Janette, noticing that her husband was languishing apart from the director, used the birth of their grandchild to plan a trip to London that would naturally facilitate the men’s reunion. Emilio recalls the teary-eyed encounter as if it happened yesterday. “[Kubrick] stood still for a few seconds without saying anything, just looking at me. Then he came toward me, smiled, and just said, ‘Welcome back.’”

Emilio stayed by Kubrick’s side for the rest of the director’s life. In fact, during the last years of making Eyes Wide Shut, the director kept him closer than he had for any of his previous films, even giving him a small cameo. Their relationship had silently evolved into a tender friendship. Emilio was no longer primarily Kubrick’s chauffeur, but the sidekick with whom the technology-obsessed director would stay up late into the night, sitting on the floor deciphering the manual of the latest VCR or microwave oven he had bought. (Kubrick loved microwave ovens.)

VI. PURPOSE AND THRILL

Watching Infascelli and producer Inti Carboni put the final touches on their documentary at Frame By Frame, a post-production facility in Rome’s Prati neighborhood, brings up a delicate but persistent question. Was Emilio and Stanley’s a mutually enriching relationship, or is it the story of a humble, hard-working man who sacrificed his own ambitions to serve a strongerwilled genius?

It isn’t difficult to see what Emilio did for Kubrick. By going beyond the role he was hired for to become an electrician, plumber, ersatz vet, occasional substitute dad, gardener, carpenter, builder, and best buddy to Kubrick and his family, the one-time race car driver enabled the director to create a selfcontained, controlled economy, an isolated citadel in which the filmmaker’s worst phobias – waste, haste, carelessness to details, hugging, germs – were kept at bay. Emilio enabled Kubrick to realize his creative vision in near-complete autonomy.

But as Infascelli puts it, “It is unclear what spiritual function or void Kubrick filled for Emilio. Emilio’s life was full when Stanley arrived in it, and it was already fast. He had a wife and two kids and a passion that he was good at: racing. Who knows where that could have led him. Still, something was missing, he was alone, he hadn’t met his perfect match.”

Indeed, Emilio had deserted his roots and his home to go settle in a foreign country; there, he had learned to drive and speak a new language with the eventual goal of becoming a race car driver. At one point, he was competing against Emerson Fittipaldi, James Hunt, and Niki Lauda, all of whom went on to become Formula One champions.

Yet it was in working for a strange American filmmaker that the farmer from Cassino found the purpose and thrill he had been looking for all his life. Looking back, he says, “Everyday it was something different, something new.”

By SULEMAN ANAYA