Fandom at the Grand Palais: Michael Jackson On The Wall in Paris

|Jasmine Amussen

I was born in 1989, when Jackson was wrapping up his tour for Bad, having sold out Wembley Stadium seven times and performed for an estimated 4.4 million people. I grew up culturally aware of Michael Jackson – as a Black southerner, it was impossible not to – but by the time I chose my own music, he had stopped making his, was facing child molestation charges, and was broke. He was neither recognizable nor real; he was a commodity, a messed up California fantasy that sold newspapers, and then he was dead. My native internet had so much trouble believing it that it fell apart. Google thought it was under a DDoS attack and halted related searches; Twitter and Wikipedia crashed. AOL Instant Messenger was offline for 40 minutes, later describing the episode as a “seminal moment in Internet history,” unlike anything they’d seen in scope or depth.

Michael Jackson was around in spirit, of course. He was at the Super Bowl in 2016, when

Beyoncé showed up in a homage to his signature military jacket to perform “Formation,” and in the music video for Rae Sremmurd’s “Black Beatles,” channeled by a version of his famous red “Beat It” jacket worn by Gucci Mane. Wearing Michael Jackson’s wardrobe says, “This is my divine right. I am the descendent of kings.”

Or maybe it means you visited Michael Jackson: On the Wall, a summer exhibition at London’s National Portrait Gallery (NPG) which re-opens today at the Grand Palais in Paris, celebrating the king of pop around what would have been his 60th birthday, for which Jackson-inspired merchandise – glitter socks, bow ties, a fedora – was produced. On the Wall was explicitly not about that material legacy, however, instead examining Michael Jackson’s impact on contemporary art. As NPG director Dr. Nicholas Cullinan writes in the exhibition catalogue: “It is about art, artistry and artifice. It is not about biography, memorabilia or rehearsing the many opinions put forward about Jackson during his lifetime and in the decade after his death.” How do you navigate Jackson’s massive cultural legacy, without the grounding supports of his life and its reception?

Of the pieces included in the exhibition and publication – which features works that were never exhibited at the NPG, reproduced here from private collections and other inaccessible places – many seem too intimate to be accessed without a built-in emotional relationship to Jackson. Off the Wall reads as a collection of fan art and fan fiction, as though its contents live the rest of the time on fan sites like DeviantArt or Archive of Our Own – not in the world’s great art collections. Included are Dawn Mellor’s Drawings of Michael Jackson 1984-6 (1985–2011), warm and endearing works earnestly made when the artist was a teenager – peak fandom age, for most – far away from Black American culture, in the north of England of the 1980s. Mellor’s sincerity stands in contrast to Lorraine O’Grady’s The First and Last of the Modernists (2010), a series of diptychs of Charles Baudelaire and Michael Jackson – both captured in coy repose – that casts their lives and careers as bookends to the modern era. Within the NPG’s clinical presentation, Catherine Opie’s Bedside Table – excerpted from a series documenting Elizabeth Taylor’s house, remote control user guides, fake flowers, and all – is stripped of the context of the celebrities’ friendship. We are left with our own meta-voyeurism, spying on someone else’s fandom.

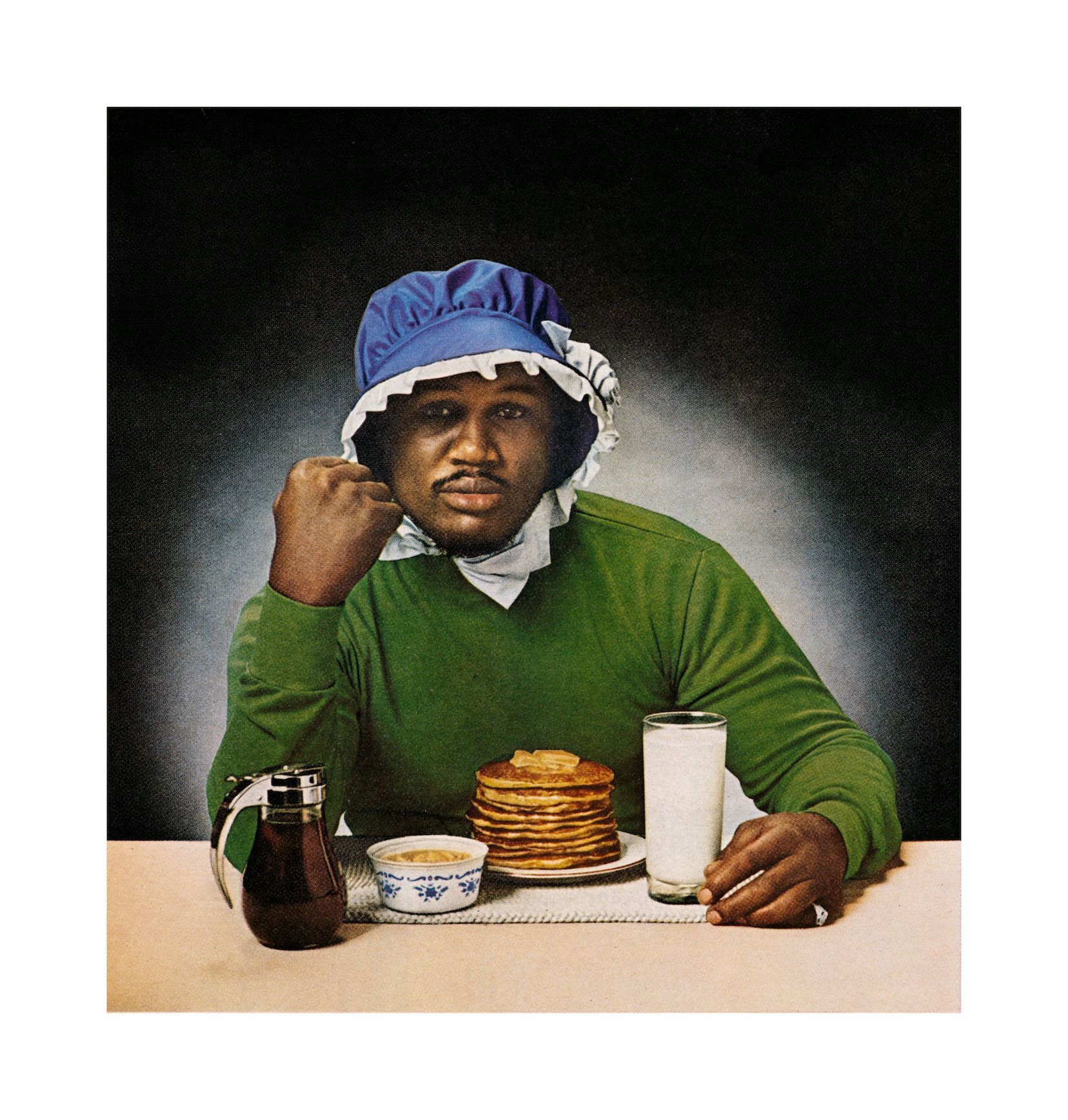

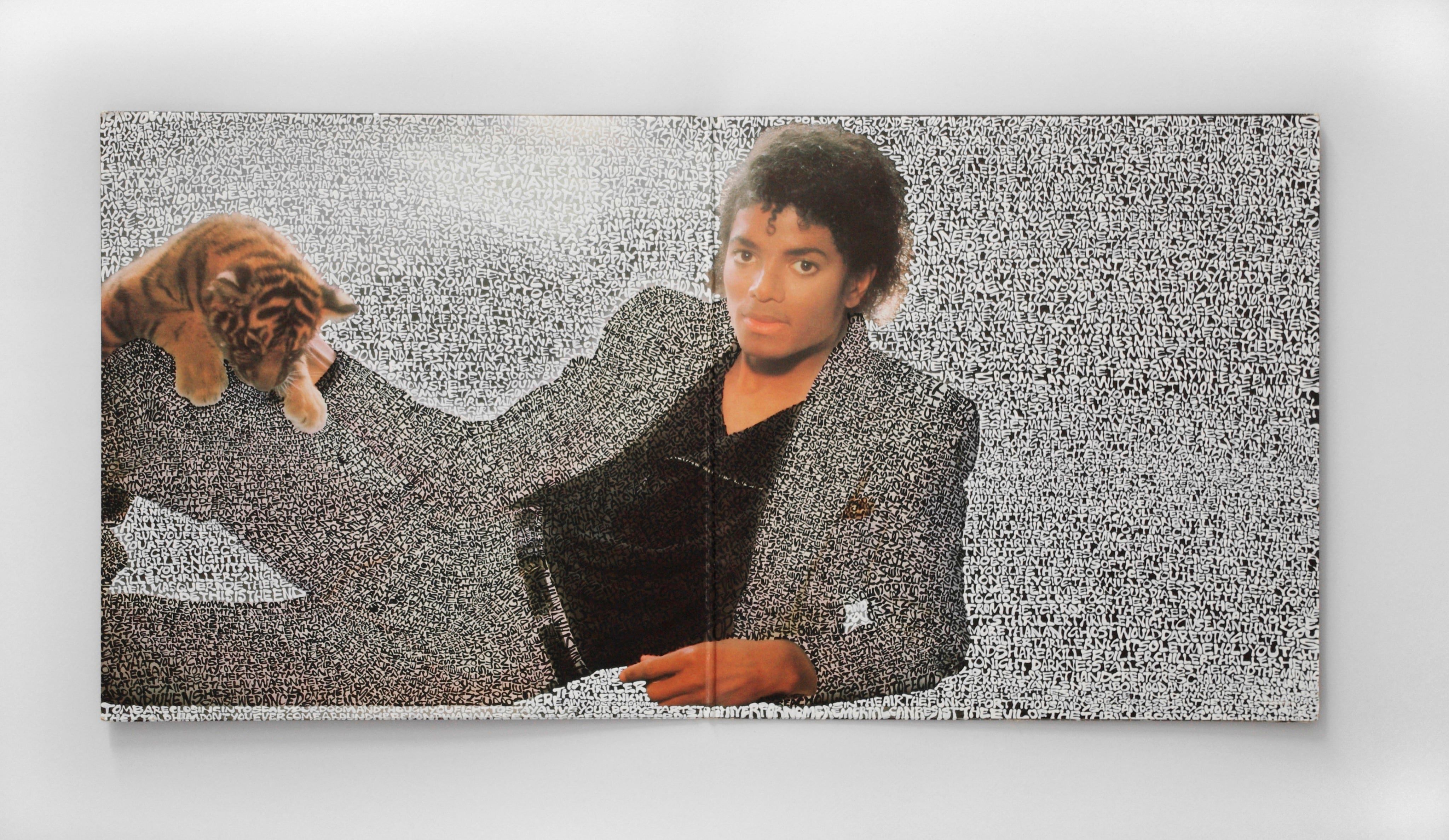

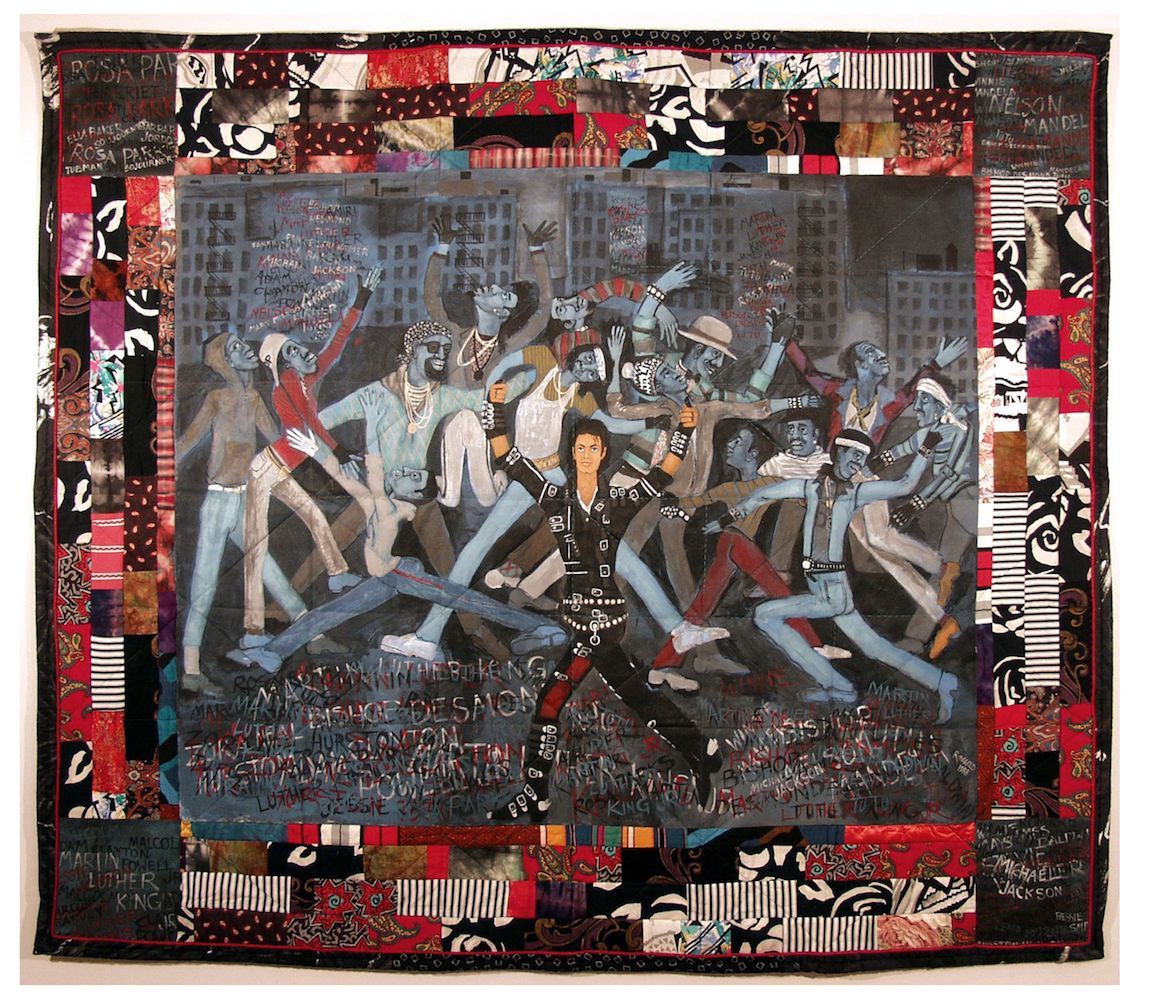

Something of a contemporary art who’s who, the On the Wall catalogue regales us with Andy Warhol’s famous MJ magazine covers and Jeff Koons’ Michael Jackson and Bubbles (1988)alongside works by KAWS, Faith Ringgold, David LaChapelle, and Kehinde Wiley. Hank Willis Thomas’ Time Can Be a Villain or a Friend (1984–2009)portrays an alternative universe Michael Jackson, handsome and stately – a still-sexy daddy, cool skinny tie and kinky hair. That alternate reality I suddenly and urgently longed for, where Michael Jackson is still alive, in this version, making music with Prince or Bowie.

Also impressive are the catalogue’s contributors, who include Zadie Smith. Her short essay, “Michael, Before and After,” speaks to those of us born a bit too late; we come to know of Jackson’s unbearable passing through her searing pain and heartbreak. She writes: “I watched him become a fun-house mirror version of what I was – mixed race – and then he was white, and then he was monstrous.” Not just some band trying out a different sound and leaving fans behind, Jackson was a beloved son leaving an entire people behind unable to believe that he wanted to be white. “It would kill us to believe it. And so we refused to do so.” The essay is illustrated by a lone photograph of young Jackson, drying off on the set of Rock and Roll Sports Classic in 1978. He is beautiful, and Smith is rapturous: “I hope that this nose, in all its broad wonder, has been returned to him in that Heaven to which Witnesses go, where everything is wonderful and there’s no pain or sadness.” In this life, though, roughly ten years on from his death, I wonder if it isn’t lucky that we will never have to watch Michael Jackson perform with a teeny bopper starlet at the VMAs. Instead, on MTV and in museums, altars to his divine legacy are everywhere.

Michael Jackson: On The Wall opens today at the Grand Palais in Paris and runs until February 14, 2019. The exhibition catalogue is published by the National Portrait Gallery (London, 2018). www.npg.org.uk

Credits

- Text: Jasmine Amussen