Sonic Fictions and Alternative Histories: Kode9

|PHILLIP PYLE

As long as there are ghosts, utopian thinking is of little use. Hauntings, seeping from the unconscious and from histories of conflict, empire, and colonialism, inflect not only the present but the future.

In times of diminished horizons, Steve Goodman, aka Kode9, has often turned to history and to the speculative art of science fiction to explore a future that accounts for the ghosts of the past while empathizing with the problems of the present. For the Scottish electronic musician, DJ, researcher, writer, and founder of the Hyperdub record label, the near future is not a place where we should expect to find a total absolution of today’s issues. In fact, one of the only constants that we should expect from the near future is a lack of constancy.

Kode9, Astro-Darien, Audio Essay cover. Designed by Lawrence Lek (Digital World Design) and Optigram (Typography), 2022.

Goodman has long worked at an affective nexus of discourses and avenues of cultural production. Having studied Afrofuturism, postmodernism, and cybernetic culture at the University of Warwick in the 1990s, he earned a PhD in philosophy and worked with the famous Cybernetic Culture Research Unit (CCRU) comprised of figures such as Mark Fisher, Sadie Plant, and Nick Land. With his practice taking shape in late 1990s London, Goodman founded the legendary Hyperdub in 2004. Soon after their first release “Sine of the Dub,” a loose dub cover of Prince’s “Sign ‘O’ the Times” by Kode9 and The Spaceape (Stephen Samuel Gordon, then known as Daddi Gee), the still embryonic label dropped Burial’s South London Burroughs (2005), the debut EP from the enigmatic and universally acclaimed electronic musician William Bevan, helping to catalyze a momentum that would eventually lead to Hyperdub being regarded as one of the world’s most prescient and sharp electronic labels.

In the past, Goodman has described the name choice of “Hyperdub” as a way of contextualizing dubstep and the burgeoning London post-hardcore soundscape through the “history of the music of the Black Atlantic.” The label is perhaps best known for a bass-driven nocturnal sound, encompassing an ocean of influences including British jungle, garage, drum and bass, Jamaican dancehall, Detroit techno, and Chicago house and footwork. However, having released music with a range of artists, producers, and rappers including Jessy Lanza, Laurel Halo, DJ Rashad, Mica Levi, Loraine James, Klein, Hype Williams, aya, and Iceboy Violet over the years, Hyperdub’s identity is tied together less by a single sound than by a common thread of conceptual rigor and research-based sonic inquiry. With each Hyperdub artist toying with distinct genres, histories, late capitalist technologies, software, and machines in their own way, Hyperdub achieves the rare sort of theory cum praxis that allows listeners and club-goers to reside, ever so briefly, in alternative worlds of sound, thought, and feeling.

On the occasion of the 20th anniversary of Hyperdub and on the eve of the publication of Sonic Faction: Audio Essay as Medium and Method, a book co-edited by Goodman, Justin Barton, and Maya B. Kronic, and featuring contributions from figures such as Kodwo Eshun, Lawrence Lek, and Lawrence Abu Hamdan, I interviewed Goodman via email, his preferred medium. Even through the veneer of a screen, it became even more clear to me that—to appropriate a comment left on Hyperdub’s YouTube channel—Goodman’s work is a “hidden gem of this fucked up world.”

PHILLIP PYLE: In addition to continually putting out releases with artists that you've been working with for a decade or more, such as Burial and Jessy Lanza, Hyperdub has always embraced what's emerging on the peripheries of sound. How do you stay attuned to newness, especially considering that you also have your own music and research practices? Can you also tell me a bit about how you see the earlier wave of Hyperdub releases relating to this new generation of artists?

STEVE GOODMAN: I think Hyperdub—the artists we work with and the music we release—functions as a kind of attractor network and filter system, so much of the new music we sign has come through friends or friends of friends. Jessy Lanza is a good example of that. We also connected with Burial because he used to read the Hyperdub blog around 2002 before we were even a label. Occasionally, I’ll have a chance meeting with someone, and we click. I was asked to do a b2b with Tim Reaper at Unsound Festival a few years ago, which was a very intense set, so I asked him if he wanted to do a release. I think the label has mutated through a few phases over the years, either in relation to scenes we were part of, or following the paths of artists sending out their own sound probes. Right now, perhaps reflecting how scattered electronic scenes are, we seem to be working with a generation firing off their own flares in the dark as opposed to everyone charging in the same direction.

PP: You released compilations to accompany the fifth and 10th anniversaries of Hyperdub. You haven't done the same with the 20th anniversary (at least so far), but you have been doing anniversary shows across Europe and the US. Might that have to do with what you're saying about how this most recent generation is "firing off their own flares" and the Hyperdub sound not being as cohesive or unidirectional as it was, say, 10 years ago?

SG: When we did our 10th anniversary 6x CD compilation, it was a great chance to thematically group how the label’s releases had evolved up to that point, looking both forward and backward. I don’t know, this year I’ve been more excited by doing a bunch of events to celebrate our birthday and doing some history of the label’s extended DJ sets. It’s a really interesting challenge for me to find ways of navigating through this labyrinth of over 1,000 tracks from our catalog doing Hyperdub-only sets. I’ve just had a recording of my set from the Hyperdub show at Fabric from March go online. That’s just one pathway. In October, I’m planning to do one that lasts six hours, so I can really get lost in the deeper recesses of the label. The idea of doing a compilation didn’t really excite me this year. We’ve done them before. I feel digital media today is set up for listeners to customize their experience any way they want, to construct their own playlists and so on. We did a digital compilation with Adult Swim for our 15th anniversary. While it’s got a lot of good tracks on it, I found that a bit of a random listening experience.

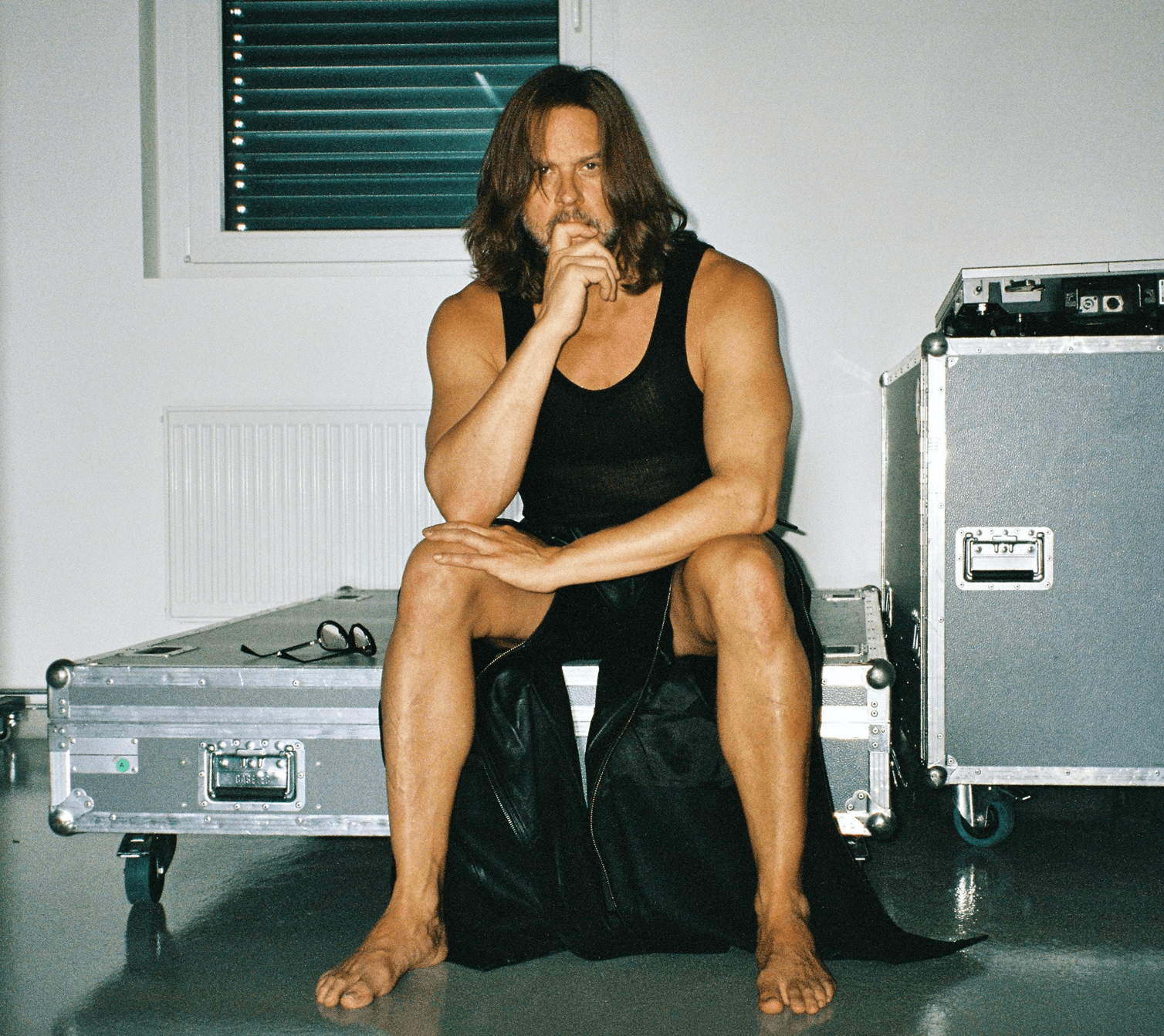

Kode9 portrait. Photo: Letizia Cigliutti.

PP: While Hyperdub has roots in London, you first began DJing in Scotland, where you are from. I'm curious if you feel like there's a different sensibility compared to electronic musicians from London? Also, considering that Hyperdub has expanded both within the UK and globally, would it be remiss to say that the label still centers around a "UK sound?"

SG: I would hate to generalize about Scottish musicians, but one thing in common with some of my favorite recent electronic musicians from there, such as Rustie or Hudson Mohawke, is they are definitely not purists. They have no issue slamming together techno and rave culture with rap production, for example. I’ve lived in London for over 20 years, and loved music from here for about 30, but definitely feel like I bring a slightly alien, impure perspective. The label also takes impurity as a virtue, so even the UK producers are weirdos in their own respective scenes—I love that.

PP: Your music is heavily informed by research. How have your writing and research practices interacted with your music as of late? Did the process of editing Sonic Faction, for instance, inspire any new material that you're currently working on?

SG: At the moment, I’m enjoying simply making tracks to DJ with, but my last large project fed into the Sonic Faction book project. It was a sonic fiction which manifested as an installation, an audio essay (Astro-Darien), a video essay, a live A/V set, and an album (Escapology). It’s probably the first time my writing and production practices have come together so tightly, as previously they would really pull in different directions. I set up the Hyperdub sub label, Flatlines, in 2019 precisely for these kinds of projects which exist in an impure interzone between music, sonic abstraction, radio documentary, radio drama, poetry, science fiction, and theory. The project has aspects of all of these but somehow belongs to none of them.

Sonic Faction, co-edited with Maya. B Kronic and Justin Barton and published by Urbanomic, is a kind of manifesto for Flatlines, focusing mostly on the first three releases on that label (but also with loads of other contributions attempting to complicate rather than define this medium), and revolving around this idea of the audio essay, which is a very open format and a way of sonically activating texts and encouraging collective listening situations. The book emerged out of a couple of these situations at KARST gallery in Plymouth and Iklecktik in South London over the last few years, and the launch for the book at the ICA in October will pursue these ideas further. It outlines some of the context for Flatlines, but also connects to the experiments of groups of which I was a member, the CCRU in the 1990s and Audint in the 2010s.

Left to right: Audint, Unsound-Undead (Published by Urbanomic, 2019) and Optigram x Kode9 collaboration.

PP: Speaking of the CCRU, next year marks the 30th anniversary of its founding. Did you have a sense of how prescient the CCRU would prove to be during your time in Warwick?

SG: The prescience isn’t surprising, as much of what CCRU was interested in was refracted through near future science fiction. The CCRU was a convergence of a group of researchers coming from quite disparate backgrounds. When its affiliates diverged at the turn of the century, its impact seemed to lay dormant or unacknowledged until much more recently. I think what was actually going on was that each of its former members were, in their own ways, processing what happened, the advances that were made, what was learned, and implementing them in their own work. Retrospectively, the impact crater seems to be pretty wide. The tendencies we were following were the rippling effects and agency of emerging technologies and the wave patterns of deep time processes that are embryonic and not yet fully actualized, yet at the same time were apparent through scattered clues in popular culture.

In relation to music, I definitely consider [Mark] Fisher, [Kodwo] Eshun, and [Simon] Reynolds a generation of writers that were a bit older than me, that I looked up to, learned a lot from, and even where I disagreed with some of their conclusions, they framed the way I thought about music, theory, and technology.

Installation view of Lawrence Lek, Black Cloud Highway, Sadie Coles, London, 2023.

PP: Your work often deals with catastrophic events and narratives, particularly those with a tie to colonialism, empire, and diaspora. Astro-Darien, for instance, is described as “a sonic fiction about simulation, presenting an alternative history of the Scottish Space Programme, haunted by the ghosts of the British Empire.” While I understand that audio essays differ from your DJing or the tracks you produce, do you find that your political interests inform your music in other ways?

SG: I have a number of sonic practices from DJing, producing, running a record label, the composition of audio essays, writing, and theorization, etc. Each throws up its own pragmatic problems, so I tend to work from the bottom up, dealing with specific challenges as they present themselves rather than with some overarching ideology which dictates what I do aesthetically. That being said, I have spent a lot of time thinking about how sound and music contributes to the affective environment of contemporary capitalism. Working within a somewhat compromised music industry, that presents a series of open questions I don’t have any conclusive answers to.

PP: Do those interests factor into the future you envision for Hyperdub?

SG: For all my theorizing about futurity, I really don’t have much to say about the future I envision for Hyperdub beyond the music in the pipeline. I know that we have some amazing albums coming out next year, but beyond that, who knows? I am, however, clear that the model of what record labels were feels increasingly redundant and is in a process of transition. I’m excited to see how that pans out.

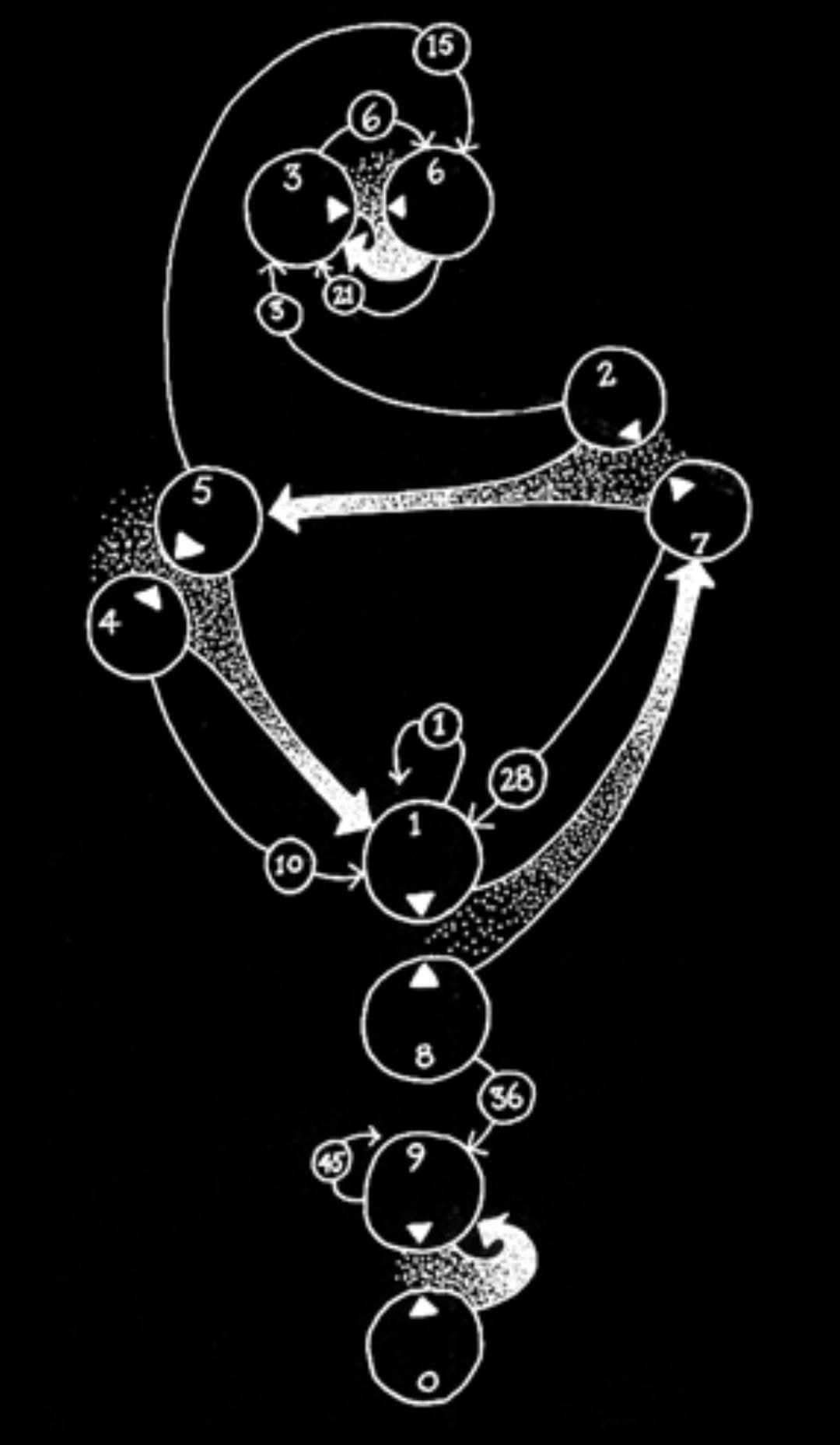

CCRU numogram.

Credits

- Text: PHILLIP PYLE

Related Content

Lankum's Antidote To Alienation

Fakethias’ Infinite Horizon

032c Guest List - Makko

The Dare Knows What's Wrong with New York

With Love From Death Beach, Casey Spooner

Who Wants to Be a Human Jukebox? Richie Hawtin

Where in the world is Paris Texas?

A Specialist in Club Music: VTSS

All Networks Lead Through Kansas: The Text Image

Gated Nightmares: Herrensauna’s Cem Dukkha

Yeat: American Truths

Abusing Technology with Kim Gordon