GRUPPE Wants to Haunt and Heal You

|Cassidy George

If we could conceive of the liminal space between the analogue and digital worlds as something akin to a wormhole – a theoretical, tunnel-like structure connecting two disparate points in the screen-time continuum – reading Gruppe is like traveling through it. First conceived as a digital platform in 2017, Gruppe has since evolved into a series of physical “editions” that take the form of an experimental art and fashion publication. With the release of each issue, Gruppe further solidifies its position as one of the most astute barometers – and predictors – of contemporary visual culture in print today.

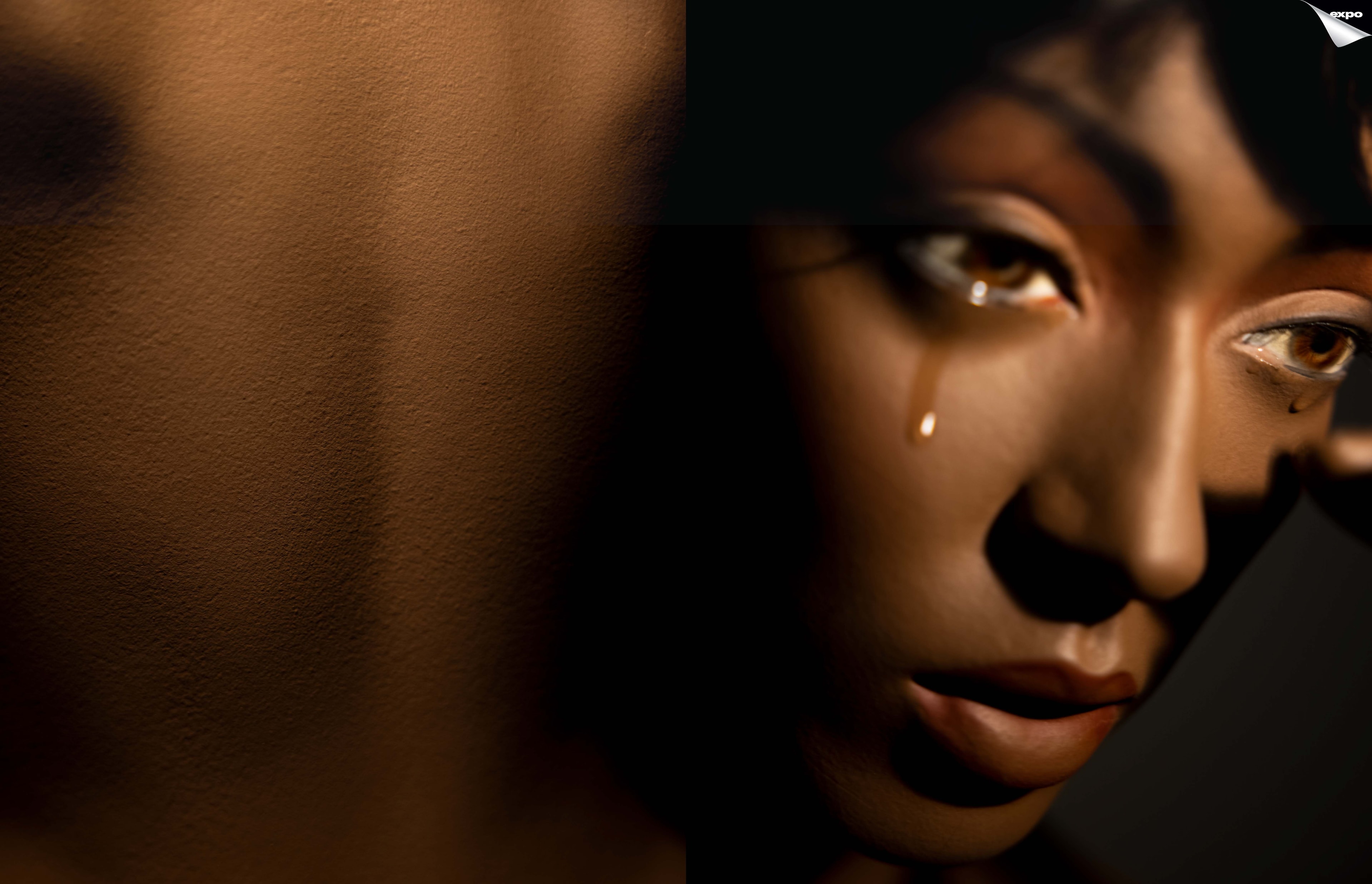

Issue 4 – Gruppe’s most recent release – is an immersive experience that beckons viewers into a grotesque, mystifying, and brutally-honest world, challenging them to navigate through a haunting series of prompts about the numbing and even disgusting realities of life in the 2020s. Its winding editorial roads explore the psychology of desire and invert the normative readings of internet phenomena – inviting us to reconsider incels as a literary movement, self-care as a virus, and apps as infantilizing. In the introduction, Gruppe asks readers: “What are you waiting for? Let us help you feel better.” In a new interview with Julian-Jakob Kneer (Art Curator), Nele Ruckelshausen (Editor & Text Direction), Fritz Schiffers (Creative & Art Direction), and Tim Heyduck (Creative & Fashion Direction), the Gruppe team tells 032c how they plan to do so.

It's a bold financial, creative, and emotional endeavor to start a print magazine. When you founded Gruppe, what was the core impulse there? What blank space in the world of print did you want to occupy?

We founded Gruppe in 2017 as an online platform. At that point, it just wasn’t in the realm of our financial possibilities to make a print magazine, even though that was always a distant aim. We did, however, have a clear idea of what niche we wanted to fill. We were surrounded by all these young, creative people here in Berlin – designers, photographers, artists – who didn’t really fit into any of the existing publishing spaces. Yet their style and aesthetic were being heavily drawn on by brands like Vetements at the time. We wanted to create a space to add this distinct Berlin voice to the European art and fashion scene.

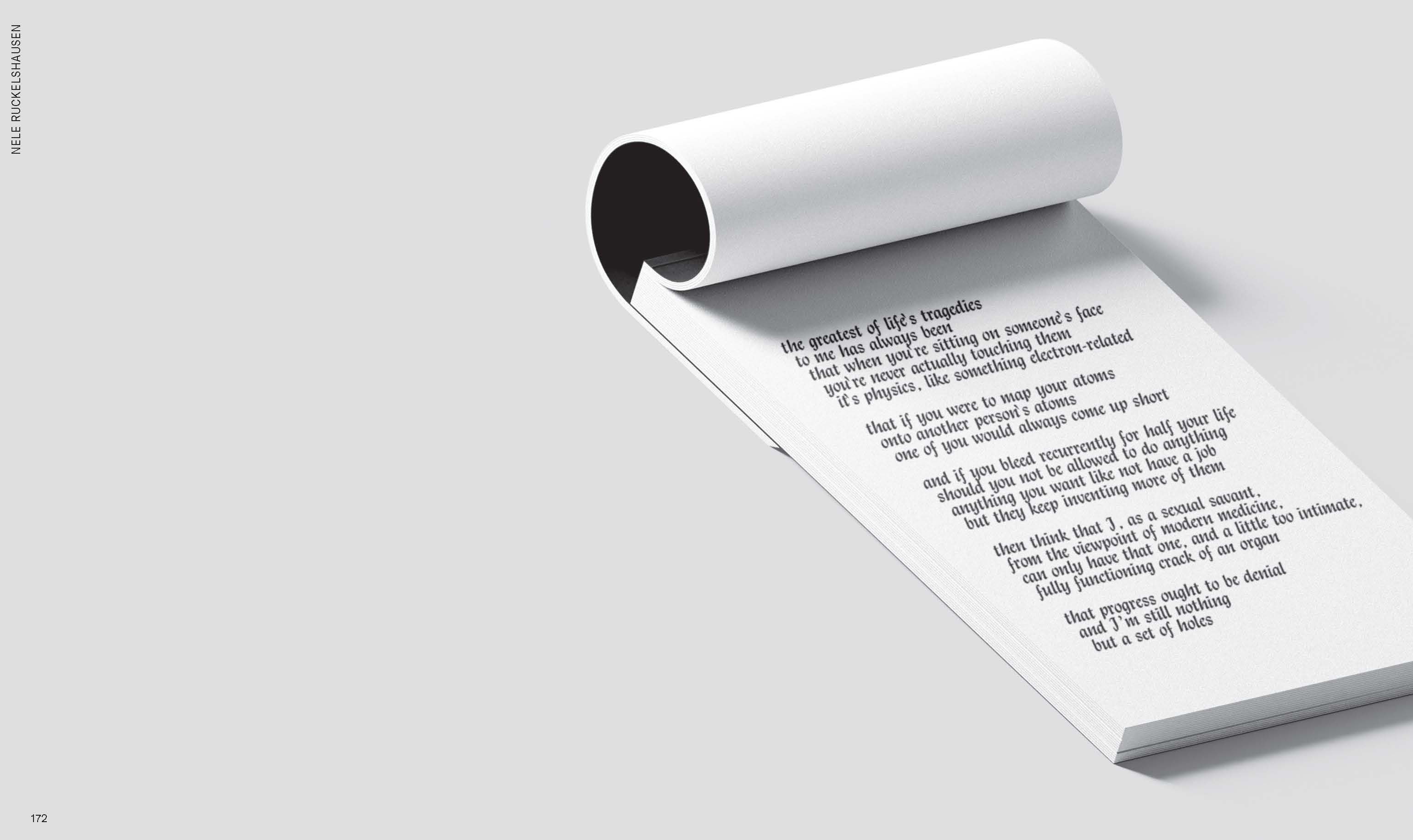

In 2018, we got an opportunity to make a print issue with art students from the Universität der Künste in Berlin – and that’s what really got us hooked on the medium. Print streamlined our process a bit: each issue is a distinct project in time, and it’s nice to end up with a physical object after you put in all this work. Still, it’s probably best to not understand Gruppe as a magazine, but more as a series of art editions. From the beginning, it was really important to us to be heavily creatively involved in the production of our content. We didn’t want to just publish things by people we found interesting or current, but to participate in shaping these future aesthetics and narratives.

What ethos would you say underpins your aesthetic and editorial universe?

A very plain way of putting it is that we’re very interested in contemporary culture, both on a purely aesthetic level and on a sociohistorical one. For each issue, we pick a certain concept or idea from contemporary culture, and we explore that idea along two tracks. You have the art, fashion, and photography content that’s really trying to put a finger on where we think culture is right now visually – or, on where we’re headed. Then you have the broader concept of the issues in the text pieces, which try to explicate why we’re there. These pieces deal with history, international politics, and economics – stuff you wouldn’t usually expect in an art and fashion magazine. Those pieces tend to drift toward the left, toward anti-imperialist, anti-capitalist theory. Perhaps that’s where a little bit of an educational mission comes into play. We have faith in our readers to want to engage a little deeper in the world. We have a lot of internal discussions about this as well – about our politics and code of conduct. We’re not content with just hopping on the virtue-signaling representation bandwagon. It’s pretty clear to everyone at this point that art and fashion exist in a bubble, but they don’t exist in a vacuum. They’re influenced by what’s happening in the world and vice versa, and it’s becoming increasingly hard to pretend that’s not the case. From the beginning, we’ve thought of the two – namely, “pop” culture on one hand, and its material roots on the other – as inextricably linked, and we try to treat them as such.

One of the theses of Issue 4 is that "we live in a haunted world." Can you further comment on that? Is the issue designed to be haunting itself?

This idea that we live in a haunted world goes back to late British writer Mark Fisher. He coined the term “hauntology” in response to the late-2000s wave of electronic music spearheaded by Burial, which resampled earlier electronic beats and vocals in an eerie, ghostly style. To Fisher, that musical style became a metaphor for how culture at large has developed since the 1990s. The idea is that history has ended and the present is just kind of a big, wafting cloud, billowing out into infinity. Cultural phenomena appear and reappear from the mist, but there’s no real sense of direction, no real emotion or purpose. Everything is already a shadow of itself.

That feeling of irreality, what filmmaker Adam Curtis would call “hypernormalisation,” is something we’ve touched on in several issues, probably because it keeps reasserting itself – first with the Trump presidency, then with the pandemic, and now with the war in Ukraine. It feels as though we’re living through these momentous times, yet the default state remains a more or less dissociated, depressive hedonism. It’s funny, because before every new issue we set the intention to keep things a little lighter or “more friendly,” then we always end up with something pretty dark. But that’s a function of the world we live in.

You also explore the ways in which the pandemic has infantilized us and increased our dependence on modern forms of servitude. Can you describe what you mean by the “self-care paradox of the service economy”?

“Self-care” is one of those terms that didn’t seem to exist before 2015, and now it’s become so ubiquitous that it has virtually transmuted the structure of our desire – a bit like a virus, maybe. A very generous reading of self-care is as an attempt to carve out time and space for yourself that isn’t colonized by the interests of others. But by now, self-care is completely conflated with self-indulgence and selfish consumption. It’s been fully digested and repurposed for corporate ends, and the pandemic accelerated that trend. Because we were all so exhausted and depressed and limited in our movement, our willingness to self-indulge just went through the roof. This idea of “you’re allowed to treat yourself” now permeates the entire world of advertising – from food and grocery delivery to ride services and so on. This is what Jude Macannuco talks about in his text piece for the last issue: how companies increasingly take on the role of mothering us, spoiling us. They even speak to us like children.

The paradox is that you think you’re treating and serving yourself in indulging in these services, but you’re actually being served by others. These companies are not just abstract colorful little icons that exist only in the app store; they’re built on the physical and often precarious labor of other people. And of course, we’ve been relying on this type of labor for all kinds of products and services for a long time. But the extent to which we’re outsourcing our quotidian tasks – cleaning, making meals, getting around – to other people, some of whom live right next to us, is unprecedented.

How do you see the fashion, art, and culture industries as fitting into this paradox?

Fashion, art, and entertainment are definitely playing their part in this era of indulgence, though they don’t fit as neatly into the self-care paradox as, say, getting your groceries delivered. But like all other industries, they are increasingly concerned with convenience and with presenting themselves as “necessary indulgences”: Insta-shoppable fast fashion, Netflix shows specifically designed for binge-watching – all that low-nutritional, fast-paced, easily consumable content out there. The scope of things we feel that we ‘need’ in our lives is constantly broadening – and broadening from things to services. It has to, since continuous economic growth is the stated goal of any capitalist economy. And then when you dig down into it, especially with fashion, of course, at one point you always get to the blood, sweat, and tears – people in or from third world countries doing strenuous, underpaid labor to keep the whole machine running. Everyone knows this, but no one really knows how it could be any other way. That’s the broader paradox here. In this context, it’s important to reiterate that our goal is to explore fashion as a cultural phenomenon – not as a product. The only thing we’re trying to sell is the magazine.

You marketed Gruppe's past issues (facetiously) as vehicles for "the joy of breaking free from the tyranny of commodified desire." But in all seriousness, is that an aim of yours? What else can we do to break free from this tyranny?

That would be a pretty ludicrous cause to take up in earnest. With the advertising for the last issue, we simply wanted to parody the hyper-libidinal marketing strategies that were born in the Mad Men era and have been taken to new extremes in recent years – think of the Kendall Jenner Pepsi protest clip, et cetera. So a kind of meta-level inversion of the promise of not just satisfying your immediate desires, but eliminating them completely. "Don’t be fooled into buying things, buy our magazine” – the ultimate product, that sort of thing.

Our aim is the one stated earlier, to explore visual or cultural trends, and to ask what they mean. It’s not really clear that that enables us to break free from the ‘tyranny’ – it doesn’t really seem like it at present. It just seems to make us all really depressed and anxious. But within ourselves, we instinctively all hold it with Zizek: why be happy when you could be interesting?

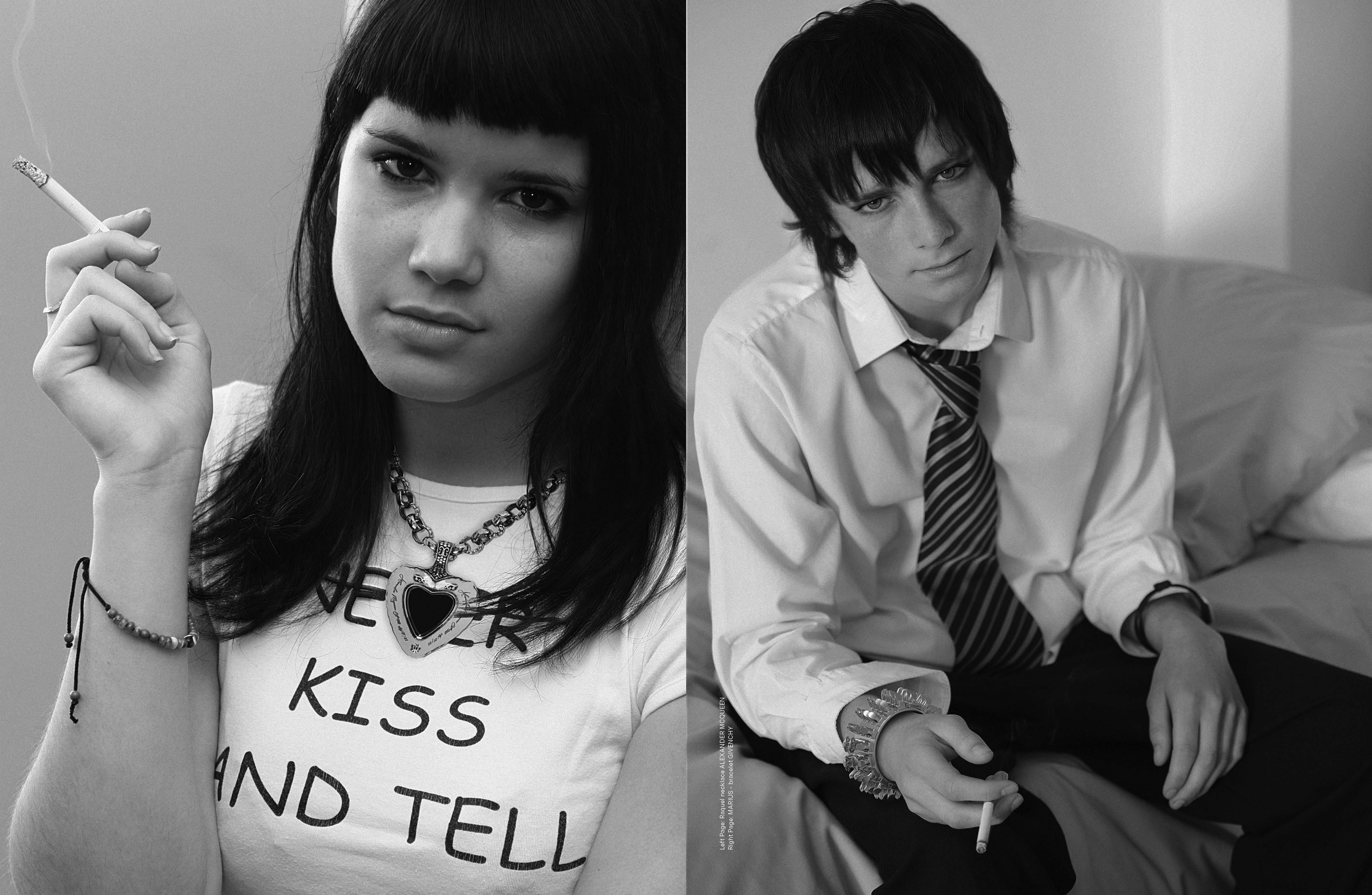

Creative & Art Direction FRITZ SCHIFFERS Creative & Fashion Direction TIM HEYDUCK Art Curation JULIAN-JAKOB KNEER Editor & Text Direction NELE RUCKELSHAUSEN Executive Editor BEN JACKSON Graphic Design MARIJN DEGENAAR

Credits

- Text: Cassidy George

Related Content

DEMNA GVASALIA on Vetements, Balenciaga, and THE SYSTEM

SECOND ACID WINTER: The Roots of Fashion’s Rave Revival

THE AGE OF UNPEACE: MARK LEONARD Explains How Connectivity Causes Conflict – and How to Cope

THE BIG FLAT NOW: Power, Flatness, and Nowness in the Third Millennium

JASSS: Wild Dreaming in a World of Service

Shimmering, Twisted, Tangible: Meet the Sci Fi Cinematographer Behind Ex Machina