MICHAEL HEIZER: Desert City

|Mahfuz Sultan

“We’re living in a world that’s technological and primordial simultaneously. I guess the idea is to make art that reflects this premise.” – MICHAEL HEIZER

Michael Heizer’s work on City began in 1970, when the artist recruited a pilot for an aerial property search above the desert surrounding Las Vegas. Flying over Garden Valley, Nevada, he spotted the plot he would acquire as the site of his sculptural magnum opus. Heizer began furtively building City there in 1972. Decades later, it was announced that 2020 would be the year of its completion, although exactly when it will be accessible remains to be seen. “Over the years we saw how the thing stood the test of time, what didn’t work, what had to be rebuilt, what happened when the valley flooded, in different climates,” he told The New York Times in a rare interview in 2015. The public has been waiting to see the secret City for half a century, but that’s a blip on Heizer’s timeline for the work: “It’s part of nature, here for the millennia.”

In my memory the deserts of the West are all one desert; fact and fiction wear the same dress; events far apart in space and time sit side by side in open concourse. Michael Heizer’s City (1972–), a mile and a half-long unfinished complex of mounds and declivities and deep furrows that split the horizon line, shares the same white expanse as the Nevada Test Site, a facility where some 100 atmospheric tests of nuclear bombs were conducted. In Las Vegas, they used to say that you could see the mushroom cloud from your front lawn and that the air smelled like it was going to snow. This was the same test site where Fred Moten’s father worked, the same one where Fred worked years later on leave from school, in some benighted chamber, reading literature beneath a naked light bulb. In that desert, City is one more man-made complex among many, among the server farms and bunny ranches, the trailer parks, the latter-day anchorites with their museums of scrap metal scoured from the remains of wartime facilities, and the skeletal airplane hangars now defunct and left to rot. The desert is as urban as anywhere in America, no less empty than the blocks in SoHo and the galleries that Heizer left behind in 1972. The ground under that desert is as sedimented with infrastructure as the subway, and a cowboy hat is mere affectation.

Heizer opened City: Complex One (1972–74) in the same year that Evel Knievel broke 40 bones attempting the Snake River Canyon jump. The artist scored the Earth while Thomas Pynchon sent his mythic V-2 rocket out on its parabolic path and Hunter S. Thompson stumbled, se dated to a pink, through the neon haze of the Vegas Strip. These events all inhabit one era, and Heizer is one more poet of the atomic age. The great bomb is as capable of reshaping the Earth as the tectonic shifts that drove the mountains around City up out of the sea. All of it, for better and for worse – from the smallest cut made in marble to the dynamite Heizer used to quarry Double Negative (1969–70) to the one kiloton bomb dropped at Frenchman Flat, all of it – is sculpture.

Admittedly we live in a time deeply suspicious of Land Art and its language of colonial administration and subdivision, aerial surveying and mapping, all the romantic bombast of eminent domain invoked under the aegis of art history. For Heizer’s generation, those children of the postwar period who saw the possibility of some mystic union between the sacred and the profane in that desert, City evokes the antediluvian. The cyclopeia that walked from one end of the Earth to the other carrying impossibly heavy stones in their hands, a race who left their marks in Giza, the Peloponnesus, Stonehenge, and the celestial plateaus of Mesoamerica. These were sites prepared for the sudden appearance of terrible, grimacing gods; these were the sacrificial altars upon which peasants and conquered peoples were split. From the very moment its horsemen carried the banners of Manifest Destiny into that desert and drove its tribes into sunset – into exile, internment, and death – the West has been a deeply constructed, industrially sustained fantasy. Heizer knows it: for him, City exists simultaneously in a mythological landscape pitted by lithic gods and a postmodern rush of fluorescent striping and signage radiating out of Vegas into the desert night. “We live in a schizophrenic period,” he once said to Germano Celant. “We’re living in a world that’s technological and primordial simultaneously. I guess the idea is to make art that reflects this premise.” City is indissociable from its contradictions, as mired in that causal chain of action and reaction as anything else in that desert, and that is how he dreamed it.

City shares the desert with the alien mythologies of Area 51, the polished disks glimpsed through diamonds of chain-link fence by children who grow up and move to Vegas to work the tables and forget what they saw. I imagine that the winds that carried radioactive death to hundreds on the Utah border, the drift that set the plutonium counter in Heizer’s home to shrieking, were the same Santa Ana winds that carried saturnine misery to Joan Didion in her tragic paces up and down the California coast. These are the hostile winds that fan the flames of a car burning by the side of the road. The cinema is there with Heizer too: Marilyn Monroe’s cries as Clark Gable brutally traps a mustang in John Huston’s The Misfits (1961), the erotic geology of Zabriskie Point (1970), the letter sent to Moe Green from Michael Corleone in the form of a bullet, and all the scenes of men in pastel suits digging graves in front of open trunks as casinos blink in the distance. City is a temple in the land of sinuous interstates and solitary diners strung out like iridescent pearls in the Nevada night. It is a landscape so populated with the ghosts of American modernity that Heizer could never have called it anything but City.

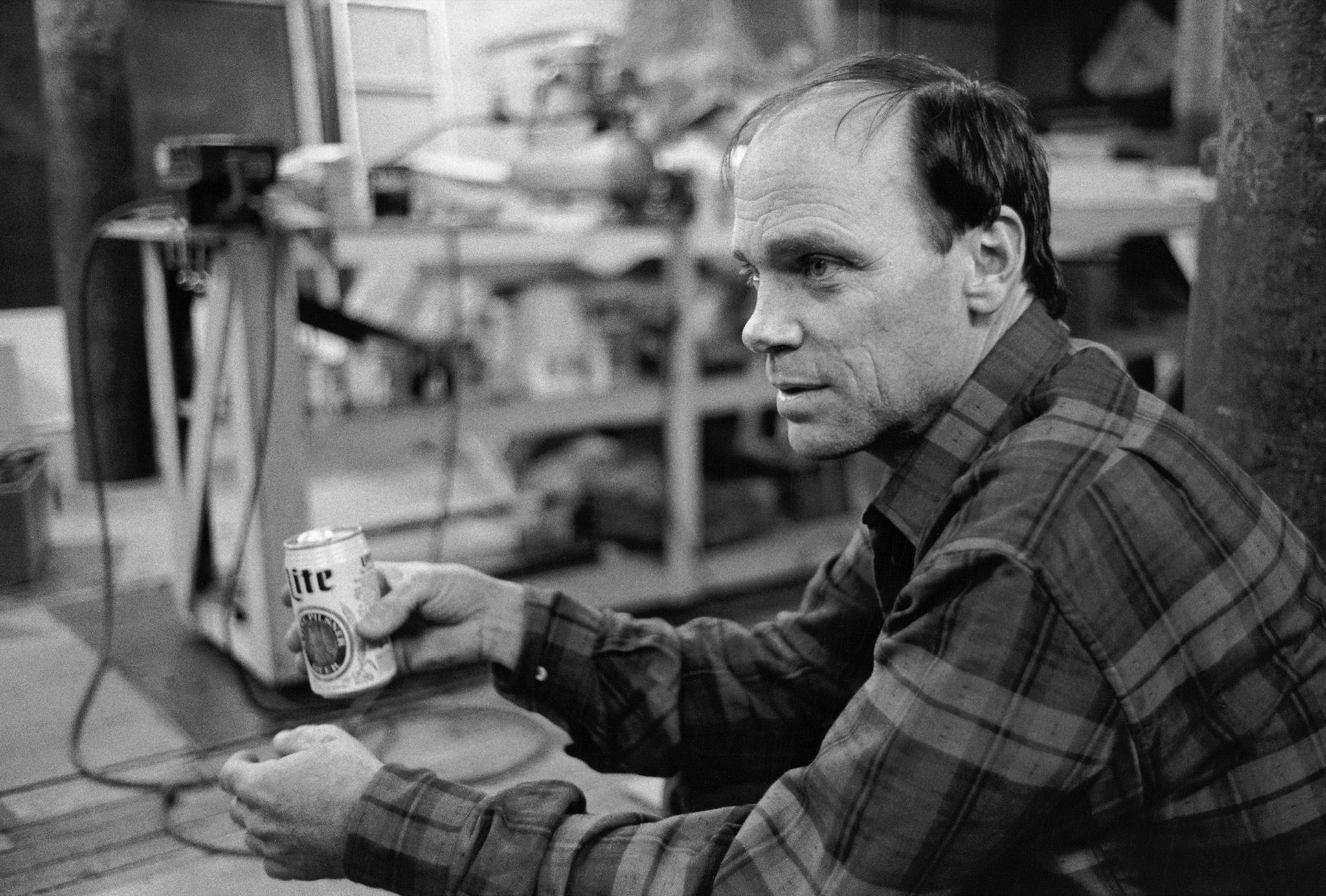

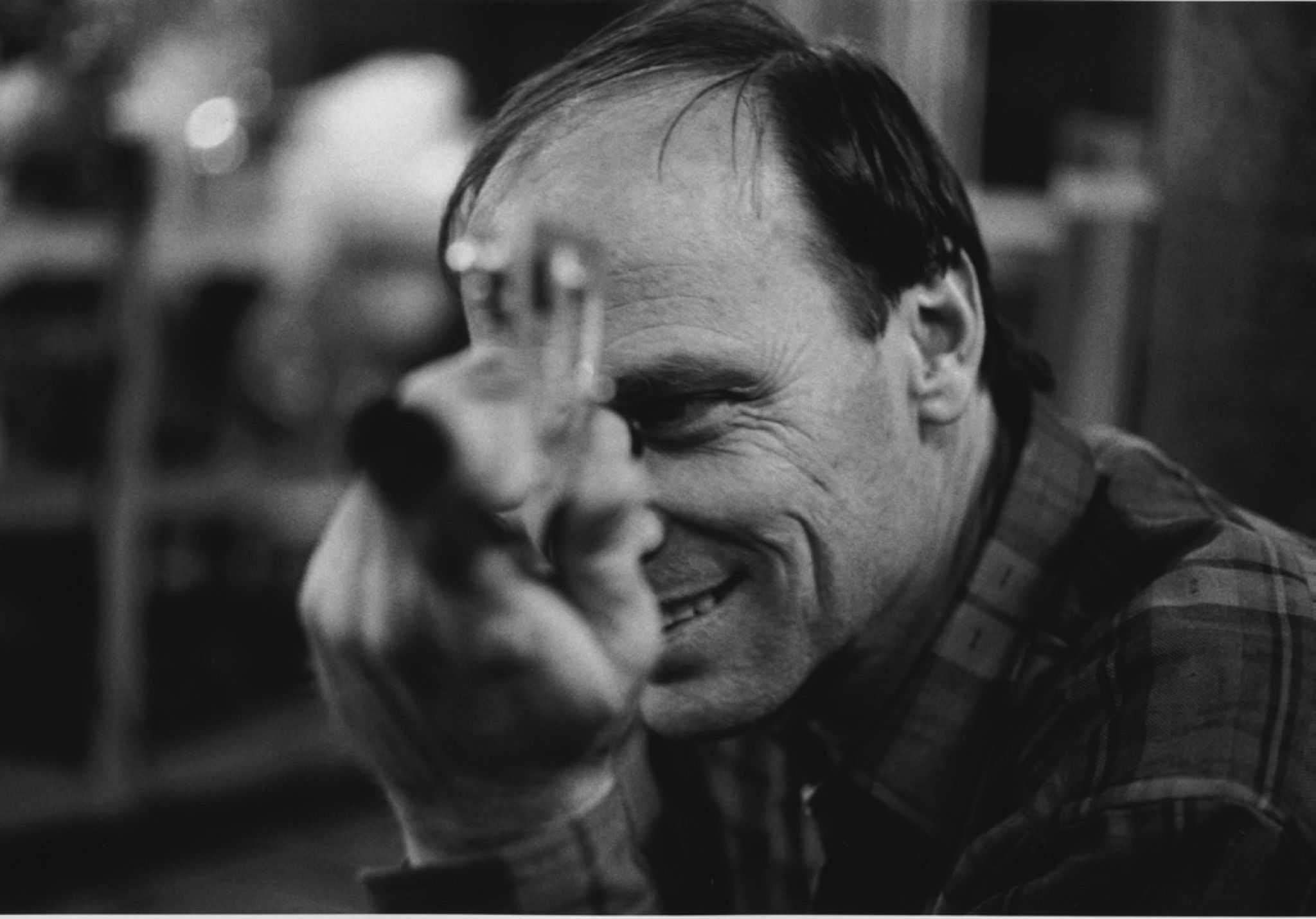

“Mike asked me to take some photographs of this model – I think to send to funders to raise money for making these large earth-moving projects.” – ARI MARCOPOULOS

Heizer left San Francisco for SoHo in 1965, the expressionistic pieties of Clyfford Still and Sam Francis in his wake. For all their differences, these painters shared the belief that line and color could raise the telluric energies that sat fallow in the western soil even beneath its asphalt and power lines. They believed that paint could hold a certain referential density in the total absence of figuration. I speak here of Francis’ accretion of spiritual force to canvas through a collision of colored planes and gesture – his Jungian archetypes and literary allusions conveyed through a play of light and forms. Standing in the embers of literary modernism, Samuel Beckett once remarked that James Joyce had said everything that needed to be said, that he had taken endless, unchecked language as far it could go. Beckett decided to push language in the opposite direction, into states of silence and inanition, into the void. At the San Francisco Art Institute, in the twilight of Abstract Expressionism, right before he turned his back and headed for New York, Heizer might have shared Beckett’s impulse.

In New York, his irregularly shaped canvases, cored and mute in tone and color, spoke of an absolute negation. In one Negative Painting (1966), four polyhedrons meet at four edges about an X-shaped hole. Thin washes of acrylic and the absence of color dramatize the flatness around the void. The jogged perimeter of the work drives the eye toward the subtracted center. It is as if a hole was punctured in what would otherwise have been a rectilinear canvas and a sudden release of energy from the wound had a distortion effect on its edges, contorting it into an uneasy communion of forms, like a supercontinent shattered by some convulsion into four islands balanced precariously on the same continental shelf. Heizer does not treat the void as a subtraction from the canvas, material that used to be there that he excised. Things are not taken away and placed somewhere else. They are vaporized, annihilated. These are the first whispers in his work of the nuclear bomb. This is the kenosis of the mystics, the emptying out of the body to leave room for spiritual energy to rush in. The mad babble of urban heresiarchs who surface in film and comic books preaching that some totalizing catastrophe – usually a big bomb left in a train station or city center – has to rent a hole in the world before man can reach some plane of self-knowledge. Heizer’s paintings diagram the detonation of something within the self.

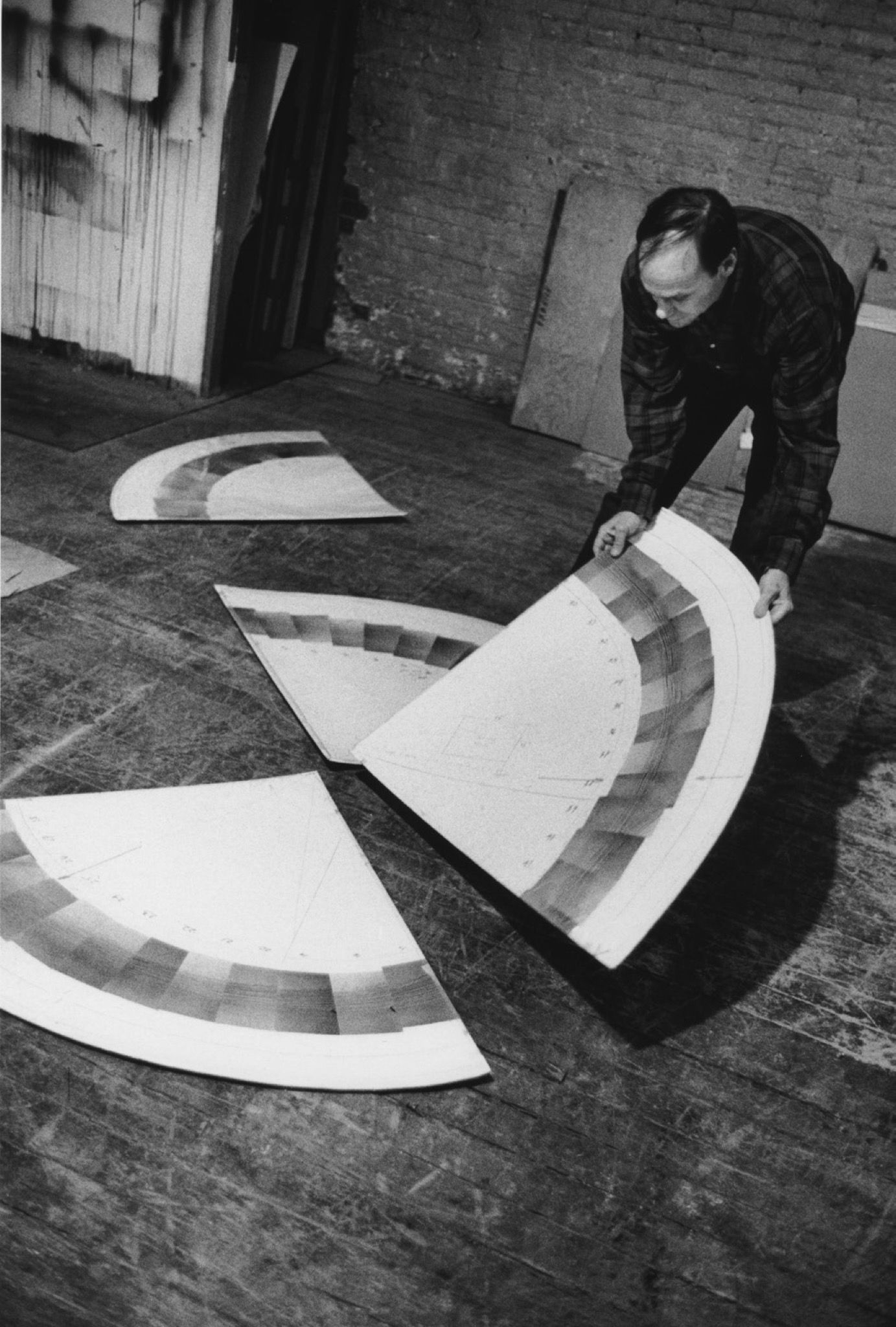

“Mike drew circles in the desert with his motorcycle. He put a spike in the ground with a rope attached, so combined with the motorcycle that made a compass in order to draw a perfect circle. Here he’s laying out a group of aerial photos of the circles he drew in the dirt. He told me he had a Honda 100cc bike. ‘Best bike to have out there,’ he said. ‘It’ll run on any fuel, you can just pour vodka in the tank and it will run.'” – ARI MARCOPOULOS

Nevertheless they are diagrams, mere simulacra – a choreography of figures that create the illusion of an infinitely receding void. When Heizer left New York for Nevada, I have to imagine that he longed for the thing itself. The intervening years between those early paintings and City were spent in various modes of experimentation in the desert. In an era of crowds and mass movements, Heizer worked in relative isolation and silence. While the students tossed paving stones at the police in Paris and American politics conflagrated itself, he made motorcycle drawings with tire tracks across the desert floor and dye paintings that disappeared into the wind. He collaborated with Walter De Maria on Mile Long Drawing (1968). He worked briefly and fitfully with Robert Smithson – a friendship that ended in recrimination and tragedy. There is no single through-line ending in that strange, sprawling megalithic city begun in 1972.

In many ways, City reflects the anthropological interests of its architect, and does so by harnessing ancient typologies to speak of the contemporary world. Heizer is the son of a renowned anthropologist and had already completed several exploratory trips to dig sites around the world by the time he started working as an artist. Right before breaking ground on Complex One in 1974, he traveled with his father again, to study the Colossi at Luxor. Complex One is trapezoidal in elevation, a mastaba that openly references the mound over the burial vault at Zoser in Saqqara. The mounds are made from the land around them, everything is re-used, the voids are no longer the totalizing absences they are in his paintings. Rather, they are occupiable depressions where a viewer can stand and see only City and the horizon line. A position that renders invisible the power lines and little signs of urban life that have since closed in around it. The horizontal banding in rough concrete recalls the staircase of the Castillo at Chichen Itza. However, it does so only typologically: Heizer is interested in the capacity of form to generate archaic resonances without necessarily reproducing their religious function or effect. On the front, what appears to be a concrete rectangle in elevation splits into fragments when viewed from the oblique. T- and L-shaped columns and concrete beams suggest a geometry of interlocking parts in arrested motion, much closer to De Stijl and the architecture of Gerrit Rietveld, or the monolithic symbols of Kazimir Malevich than some numinous outcropping in the desert left behind by an unknown race. The insistent frontality of the mound places it in dialogue with the billboards and over-scaled signage that are a part of the landscape in and around Las Vegas. The precision of its 90-degree cuts and grading at exactly the angle of repose – work that architects would call “clean” – speaks to the second machine age finishes of Minimalism.

Complex Two, completed in 1988 after a hiatus back in New York and several funding battles won and lost, is an even larger mastaba than its neighbor. Comprised of a mound, concrete seams, and the depression it was pulled out of, the earthwork exists half above and half below the horizon line. Less Cartesian than Complex One, it aspires in certain places to the curvilinear and appears more worked on by hand. Heizer laid several large monoliths against it, cast concrete stelae that appear almost heaved up from the Earth’s crust; cenotaphs to all art forms of the 20th century that fetishize building materials and leave them as potential energy on the gallery floor, indexical and lifeless. City bears similarities to bunkers and munition sheds, to the lingua franca of everyday architecture in the Nevada desert, even if its mounds are closed surfaces with no interior spaces.

Nearly a mile and a half away on the opposite side of City sits 45-90-180, a gathering of astral geometry on a broad plinth unimaginably exacting and numinous. The work consists of concrete slabs and right triangles arranged as if in service to a personal god, some tutelary deity that Heizer fashioned for himself during the long hours spent at work in the desert. These sculptures aspire to a certain mathematical abstraction, almost Pythagorean in their fealty to proportion, dimension, and scale. Heizer is not engaged in a naïve project to bring ancient spirituality back into contemporary life; rather, his structures echo the ahistorical experience of everyday life, in which the Aztecs, Dutch modern, a Judd chair, and the MGM Grand sign float side by side unmoored from place and time. His project is as concerned with historical pastiche as it is with sculpture, which fits in well with the work of Venturi & Scott Brown, Michael Graves, and other contemporaries that recast the ancient pylons and pedimented facades in the colored light of the modern metropolis.

Now, I am not another poet intoxicated by the mere mention of ancient civilizations. I am far too African for such facile orientalisms. These are the daydreams of earlier generations, of writers raised in the shadow of the early 20th century’s fixation with the myth and literature of humankind’s adolescence. Those that fill their pages with Celtic dolmans and truncated pyramids, minotaurs and the lithic architecture of the Yucatan, in an effort to read their hieratic character into modern art, when there was a copy of The Golden Bough or the Collected Works of Robert Graves on every critic’s shelf. At one time, we believed that the invocation of Achilles or Europa in the title of a Cy Twombly work had the incantory power of an ancient chant. I am critical of the philological obsession with tracking all of civilization back to a single itinerant, monolingual people that colonized the world when there was one land and one sea, when Nevada was a seabed and had not yet thrown up the volcanic rock that Heizer would pull from the landscape. One cannot sanitize a legacy of colonial occupation merely by dreaming of a halcyon past when we were all one people, set about a single sea, and the same words followed myriad and random paths toward French and Sanskrit from a single origin.

City is not a temple dedicated to the scholarly fixations of its poets. Literature about City is filled with mythologizing sentiments, as if Heizer’s decision to work in the western desert was not fundamentally influenced by its proximity to all the contested spaces of modernity, from the seizures of Native American land to the military test sites and casinos that were built upon it. I doubt if he ever believed he was working on virgin earth. He went into that desert to quarry it, and City is a postmodern dig site, more a mining operation effected with construction equipment, dynamite, and concrete retaining walls than some re-emergence of sacred architecture. Heizer was excavating the ruins of his time.

Thousands of years from now, when some cataclysm splits Nevada down to the dust we walk on today and an alien race – mute, telepathic, formless – comes across City, cracked and eroded, its fragments serried across the landscape like boundary stones, will it tell them anything about this time that resembles what we call art? No doubt they will know the family rehearsals of evacuation procedures and the shelves of canned goods and first aid kits stuffed into concrete bunkers under the backyard. They will remember in some penumbral way the strange illnesses we visited upon ourselves in the aftermath of Hiroshima and Nagasaki; the mutations in Chernobyl; they will know that we once had and lost men like Andrej Tarkovskij to toxic air released by priests we once called scientists. They will talk about us as we do of Pompeii, frozen in ash below the water table, all that remains of us left vulnerable to a sudden gust of wind. Some historian will describe the mad flight of city kids to California to found new religions and therapy groups, suicide cults and hermitages. And yet, will that future still know art, and if they do, will they recognize it in the broken concrete of City? I imagine that Heizer hopes for this, that after all the debates – about the wall and the floor; the field expanded and compressed; mediums in collision or separate and immobile, each in their own egg dissolving into faint memories; art in and for itself or against the state – City will stand in silent testament to whatever it is we seem to call art, to the irreducible remainder after all discourse has been stripped away and nothing is left save the difference between a tool, a piece of food, and an object that is neither. Heizer has been working on an art that aspires to outlive even art itself, and perhaps, for the art of any time, that is the most and the very least that can be said of it.

Credits

- Text: Mahfuz Sultan

- Photography: Ari Marcopoulos