NOT GREEDY FOR MONEY, BUT FOR THRILLS

|Sven Michaelsen

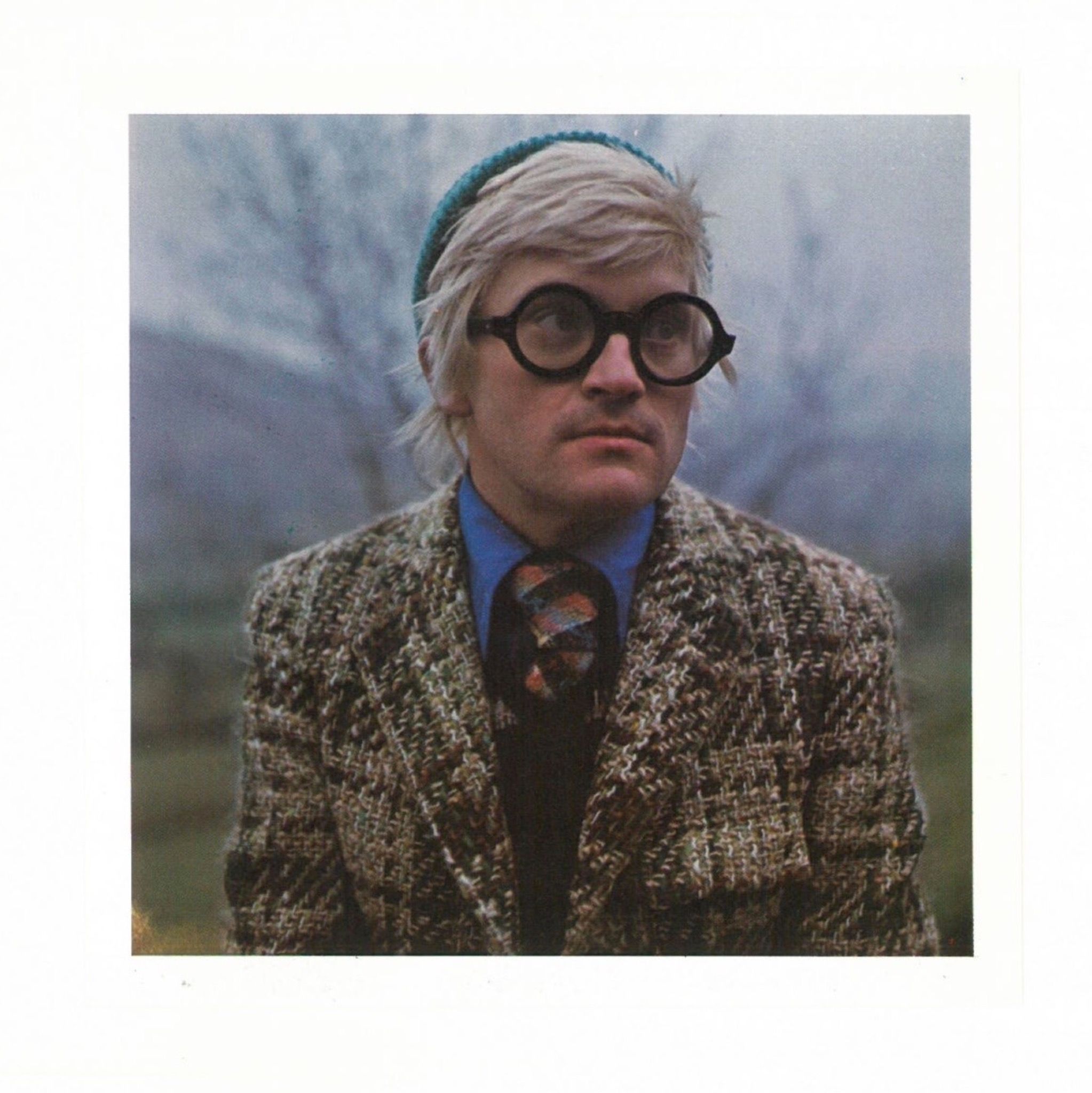

David Hockney is a living master of breaking records, in sales both at auction and at museum ticket stands.

A conversation about the artist’s emergency stash of cigarettes (2,000 of them), the ludicrous price tags on his paintings (up to 90 million dollars), and the life-giving power of curiosity.

You’d immediately sign him as a spokesperson if you were in charge of marketing for a tobacco company. “Want one?” David Hockney asks, holding out a pack of Davidoff Classic Magnums. He’s a happy smoker, the 83 year old says. “Tobacco is good for my mental health. Maybe I’d be addicted to psychopharmaceuticals if I didn’t have cigarettes and Cohiba cigars.” Hockney – son of a militant anti-smoker who participated in street demonstrations advocating for the prohibition of tobacco in the 1950s – has been smoking for 66 years. “If there is one social group that I feel I belong to, it’s the bohemians, and there is no such thing as bohemian society without smoking and drugs. People should let the bohemians live their lives; a society runs out of ideas without them.”

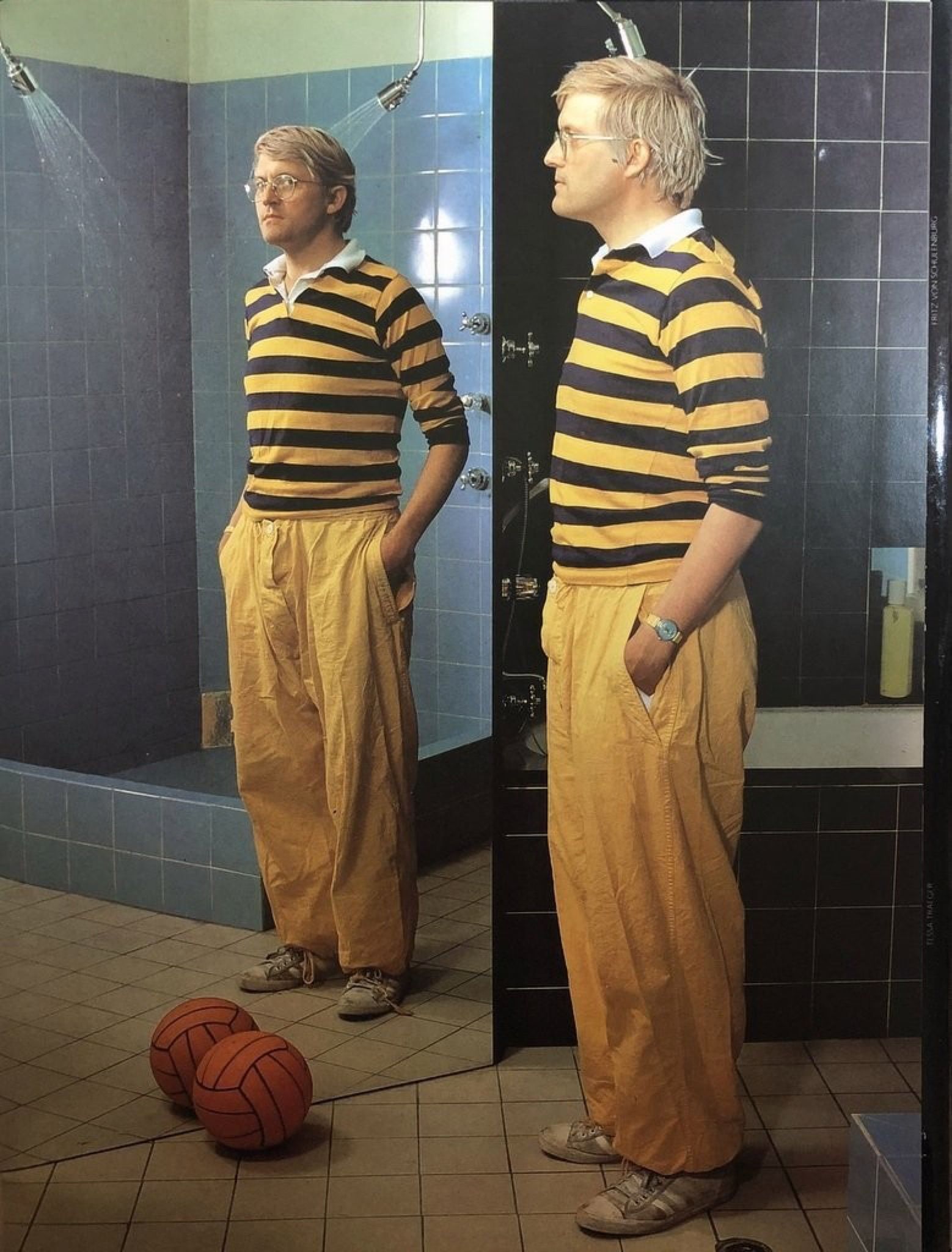

From 1979, the Brit had lived primarily in his villa on Montcalm Avenue in the Hollywood Hills, above Los Angeles. This year, on March 2, he moved into his farmhouse in Normandy with his dog, Ruby, and two assistants to paint the beginning of spring in the countryside. Two weeks later, President Emmanuel Macron imposed a nationwide lockdown. “Suddenly,” Hockney recalls, “the restaurant where I ate lunch every day was closed. Other than that, the forced isolation has changed very little in my life. I paint from the early morning until the late afternoon, and if the day is boring then I paint a boring day.”

The floor of Hockney’s studio is dotted with thousands of burn marks, and the painter’s pants and cardigan have at least a dozen cigarette holes in them. “A cigarette helps my concentration whenever I stand back from the easel and look at my painting,” he says. “Smoking gives me time to think about the gaze I paint with.” He names three colleagues who continued to smoke and who have achieved lasting fame as role models for his conviction: “Picasso turned 91, Monet, 86, Renoir, 78. And as a German, you are likely to know that the most radical anti-smoker of modern times was Adolf Hitler! If he had won the war, he would have eradicated smoking entirely.”

Nine years ago, Hockney had a mild stroke that robbed him of his speech for a few weeks. But otherwise, he says, he is in perfect health, minus a few age-related malaises. “Unfortunately, there are very few sins left in my life. I have not had any alcohol in over 20 years. If you see me drinking a beer, it’s children’s beer in my glass.” After two bottles of the alcohol-free variety, he turns off the lights at half past nine in the evening, and starts the next day between four and five in the morning.

When your painting Portrait of an Artist (Pool with Two Figures) was sold at auction in New York in 2018, you became the most expensive artist alive. Did you follow the nine-minute-long bidding?

No, I’m not interested in spectacles like that.

You destroyed the first version of the work in 1972, after six months of vain attempts to paint it. Why?

The perspective of the swimming pool and the two figures’ relationship to one another wasn’t right. I was also unsure about the choice of background. First I tried a wall, then a glass wall and mountains. To paint the new version of Portrait of an Artist was a race against the clock, since the painting was going to be shown in André Emmerich’s New York gallery in 14 days. I worked 18 hours a day, with an intensity like never before.

Portrait of an Artist depicts a traumatic separation. Your first true love, Peter Schlesinger, who had left you shortly before, is standing at the edge of the swimming pool. Schlesinger’s new boyfriend is swimming under the water. Does the pain subside once you’ve painted love fizzling out?

Yes, you gain distance from a breakup if it becomes an artistic problem of representation. Misfortune and sadness become working materials, and you look at yourself as if from the outside. Take Van Gogh. He loved painting and spent the majority of his life doing it. So he led a life full of love. But his biographers claim that his life was full of loneliness, pain, and depression. This misunderstanding pervades almost all of the biographies written about artists. Why do I paint every day? Because I don’t feel all that great when I do something else.

How close and how far away are you from Portrait of an Artist now?

The separation from Peter Schlesinger was 48 years ago, but the picture shows something that could have happened yesterday. This sense of timelessness is why the picture is still convincing to me today.

There’s a rumor that the painting was sold under false pretenses. Your biographer Christopher Simon Sykes writes: “A man walked in off the street, an American, apparently with money to spend, who gave the impression [in André Emmerich’s gallery] that he was a friend of Hockney’s and who seemed to know the painting well. Assuming him to be bona fide, Emmerich agreed to sell him the picture, the most expensive in the show, for 18,000 dollars. Within a few months the painting was with a London dealer, who took it to an art fair in Germany, and it ended up being sold to a London collector for nearly three times its New York price.” Do you know this London collector?

No.

The London collector later sold Portrait of an Artist to David Geffen for an undisclosed sum. Geffen is a Los Angeles-based music and film producer whose fortune has been estimated at more than seven billion dollars. Did Geffen ever offer you a viewing of the painting?

We both lived in Malibu in the 1990s. I visited him every once in a while to see a new movie. Then one day my picture was hanging on his wall. A couple of months later I stopped visiting Geffen, because he was annoyed that my dogs peed on his carpet.

In 1995, Geffen sold the painting to Joe Lewis for yet another undisclosed sum. Lewis is a British finance shark living in the Bahamas whose assets have been estimated at more than five billion dollars. He owns an 85 percent stake of the football club Tottenham Hotspur, three mega yachts, and an art collection featuring works by Picasso, Matisse, Lucian Freud, Henry Moore, and Francis Bacon that is valued at one billion dollars. Your painting is said to have been hanging in one of the salons of his 98-meter-long motor yacht Aviva.

I never met this man. He also never offered me a visit to see the painting. So I can’t say whether this is true.

When Lewis had the painting auctioned off by Christie’s two years ago, the first bid was 18 million dollars. Thirty seconds later, there was another bid for fifty million dollars. In the end, an anonymous telephone bidder paid 90,312,500 dollars for it. Do you have any idea who bought the painting?

No. I called Christie’s and asked for the identity of the buyer, but they said that they were sworn to absolute secrecy.

Portrait of an Artist is one of the most intimate paintings you ever made. Does it bother you when plutocrats buy your painting as a kind of penis extension?

I don’t think about it. I’m a painter who paints the here and now, and who doesn’t look back. Nostalgia is an uninteresting state of mind. I’ve only ever dealt with my past once in my life. Four years ago, I put together the monograph A Bigger Book with the book designer Hans Werner Holzwarth. The book weighs 35 kilograms and [the largest spread] is more than one and a half meters wide. Holzwarth and I spent six months going through my work from a period of sixty years. It was like psychoanalysis, making it clear to me how my artistic self has developed. Our aim with the book was that every time you’d turn a page, a new painterly aspect would show itself, and I think we succeeded. The journey through my past got me so worked up that I was unable to paint for half a year. That had never happened before. No matter how miserable I was, I could always paint.

Do you really not care whose walls your pictures are hanging on?

I really don’t care. It doesn’t matter to me who the legal owner of Portrait of an Artist is. It is my picture and it stays that way. I painted it and the copyright belongs to me. That’s what counts. The owner only owns a piece of painted canvas that will probably pass into other hands sooner or later.

The only possible way to own a painting is to paint it.

Before the auction, a Christie’s representative made the following grandiose announcement: “We rarely can say, ‘This is the one opportunity to buy the best painting from the artist.’ This is it.” Do you share this expert opinion?

No. It’s easy to see through such PR that is intended to boost the auction results. As Oscar Wilde once said, “It is only an auctioneer who can equally and impartially admire all schools of art.” All these people care about is making more money. If the Christie’s woman was right, then I painted my best painting 48 years ago. What a slap in the face! I’ve come a long way from considering Portrait of an Artist as my best work.

Were you overcome by a sense of triumph when you heard about your world record?

No, “the most expensive living artist” is not the kind of title I’m after. I felt a little bit of triumph when A Bigger Book was published. This book was a much more significant event for me.

After the auction, Peter Schlesinger told the English newspaper the Observer: “I can’t speak to its emotional element because I don’t think it’s emotional. I don’t even think it’s a portrait of me, really.” Who’s right, Schlesinger or your biographers?

He stood for photos for me in Hyde Park in London, and I painted him according to one of these photos. By definition, this is portrait.

Your world record with Portrait of an Artist lasted only six months. Last May, Rabbit, a sculpture by Jeff Koons, was auctioned off for 91.1 million dollars. Do you follow the ever-changing records of the art market?

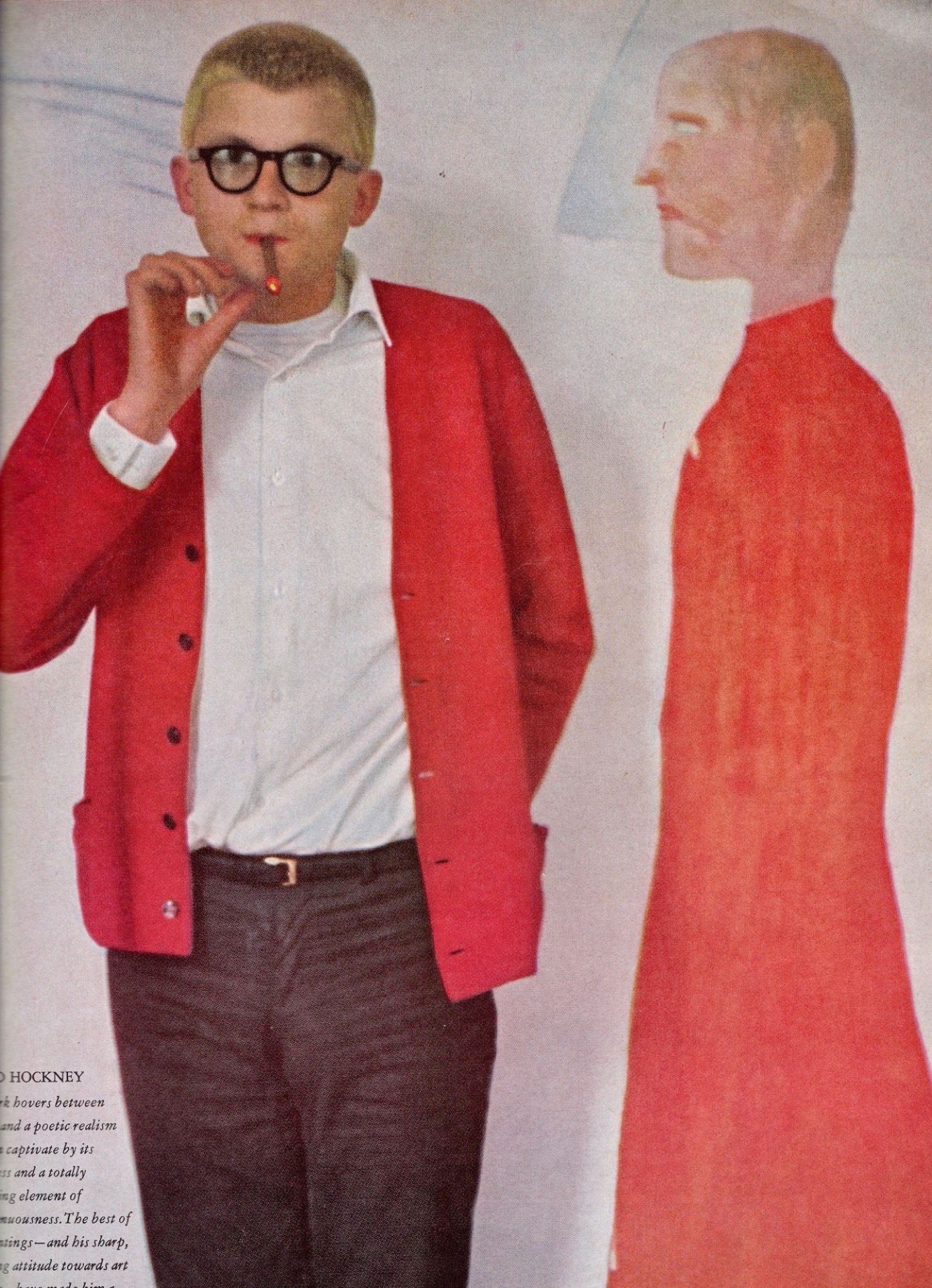

I try to ignore the art market as much as possible since sums like this are crazy. The good thing about such astronomical prices is that they guarantee a painting protection and diligent care. Anyone who spends millions wants his investment object to remain in the best possible condition so that he can sell it in due course with maximum profit. That’s a reassuring feeling for the artist. I painted my paintings in such a way that they would have a long life, and I have done this from the very beginning. The colors of my early paintings still look good because even back then I knew how to handle colors. If you add too much white, for instance, the colors change over the years.

Who do you think about while painting?

No one. I only paint my pictures for myself. I hope that what I find interesting is also interesting for others, but I would also paint if no one was interested in my paintings. I wouldn’t know what to do with myself without painting; I would feel entirely superfluous. I would go crazy after a couple of months in the swamp of idle brooding. You could see that as a curse, but I don’t.

Does it influence your painting to know that every square inch of canvas you cover with paint is worth a small fortune?

No. Greed is not foreign to me, though mine isn’t geared toward money, but rather toward exciting moments. I have the good fortune that it can make me happy to watch raindrops running down a windowpane. The sense and purpose of my paintings are pleasure and joy. They’re not supposed to do anything else.

Anger, desperation, suffering, depression, sickness, death – the dark sides of human experience hardly ever feature in your work. How do you explain this?

I take it as a compliment when my paintings are criticized as being too playful. Even a scientist in a lab needs a sense of playfulness to make a discovery. There’s no art without play.

If you’re asked about your wealth, you wave it away and say that money doesn’t interest you, since you were already “restaurant rich” in your mid-20s. What do you mean by this term?

I ate in restaurants every day and was not obliged to order the cheapest item on the menu. I ordered lobster and caviar whenever I felt like eating lobster and caviar. That’s why I’ve felt like I’m rich for 60 years. I’ve spent my life exactly the way I wanted to since I was in my early 20s. How many people do you know who could say the same thing about themselves?

Your German colleague Gerhard Richter, whose fortune is estimated at 550 million euros, recently said with a mixture of sadness and anger that it isn’t fair if a painting costs more than a house. Do you agree with him?

The most expensive painting in my first exhibition cost 300 pounds. Any teacher or lawyer could have afforded it and would be rich today. That’s why I think it’s pointless to think about whether the price of an artwork is fair or unfair.

Robb Report asked the publisher and art collector Benedikt Taschen about which artist had tortured him the most. His answer was: “David Hockney is my friend and neighbor. I visit him twice a week. A couple of years ago, he started to paint something that I knew that I wanted to have right away. When he was finished, 12 months later, I asked him to sell it to me. He shook his head and said, ‘I love my paintings, and thank God I’m wealthy enough now that I don’t have to sell them.’ We started playing a game that was half in jest and half serious. After two years, he finally sold me the painting.” What painting was he talking about?

Garden with Blue Terrace.

The painting shows the view of the garden from the blue-painted terrace of your house. What did Taschen have to put down for it?

Maybe two million dollars. I don’t really know anymore. It was a friendly price in any case.

Your life partner, Henry Geldzahler, who died in 1994, tore up your paintings when he thought they were unsuccessful. Who is able to criticize you, a living monument, today?

I miss Henry, the man and his unfailing eye. My assistants could theoretically say, “David, you didn’t get your new painting quite right.” But is that the job I’m paying them for? I think I’m my best critic. I read all the time that I’m a very prolific painter, but I’m not. Besides the drawings, I painted a dozen pictures last year at most.

Do you wish that it were more?

No. I’m 83 and could fall over dead in the next minute, but if I did, I would have left more traces behind me in art than most painters.

Artists whose powers of imagination have begun to wane often start to release work they might have rejected in better times. Have you become more self-critical or more complacent in your old age?

More self-critical. And this is one of the reasons I’ve kept more than half of my paintings for myself for the past 20 or 30 years. Like I said, I’m my greatest critic, and this critic isn’t always totally sure how successful a painting of mine is.

Fear of failure, not knowing how to continue, mental blocks – are you familiar with any of these?

No. If you go to work every morning like I do, every painterly problem vanishes into thin air sooner or later.

Your foundation owns more than 8,000 Hockneys. What’s going to happen after you die?

I haven’t decided yet.

Since you don’t have any children, it would make sense to donate your collection to a museum.

The advantage of museums is that they are not allowed to resell paintings for a profit. The disadvantage is that most of the works disappear into the depots, never to be seen again. But for an artist, being forgotten is even more mortifying than dying.

Painters like Julian Schnabel become rich and buy back their own paintings. Do you as well?

It’s beyond my means to fork out 90 million dollars for a Hockney. If I was drowning in cash, I’d like to buy back Play within a Play from 1963.

In an interview, the art dealer Larry Gagosian was asked whether inflation in his industry would carry on like this. Gagosian replied, “they say that for basketball players, anything taller than 6’8” is too much.” Can you interpret this oracular phrase?

I’ve known Larry for 45 years. In 1975, he was still selling posters with kitschy motifs in a back courtyard in Westwood; today he’s the most powerful art dealer in the world. You have to admit that he does excellent exhibitions and catalogues, but don’t ask me whether the art market is 6’8” or 6’9” – or whether the art market is a bubble that’s about to burst. Even in Rembrandt’s lifetime a Rembrandt was expensive. Unfortunately, today the price of a work of art is more important than its value. In museums, the longest lines are in front of the most expensive paintings. A lot of visitors don’t come because of the art; they come to ogle at a huge pile of money.

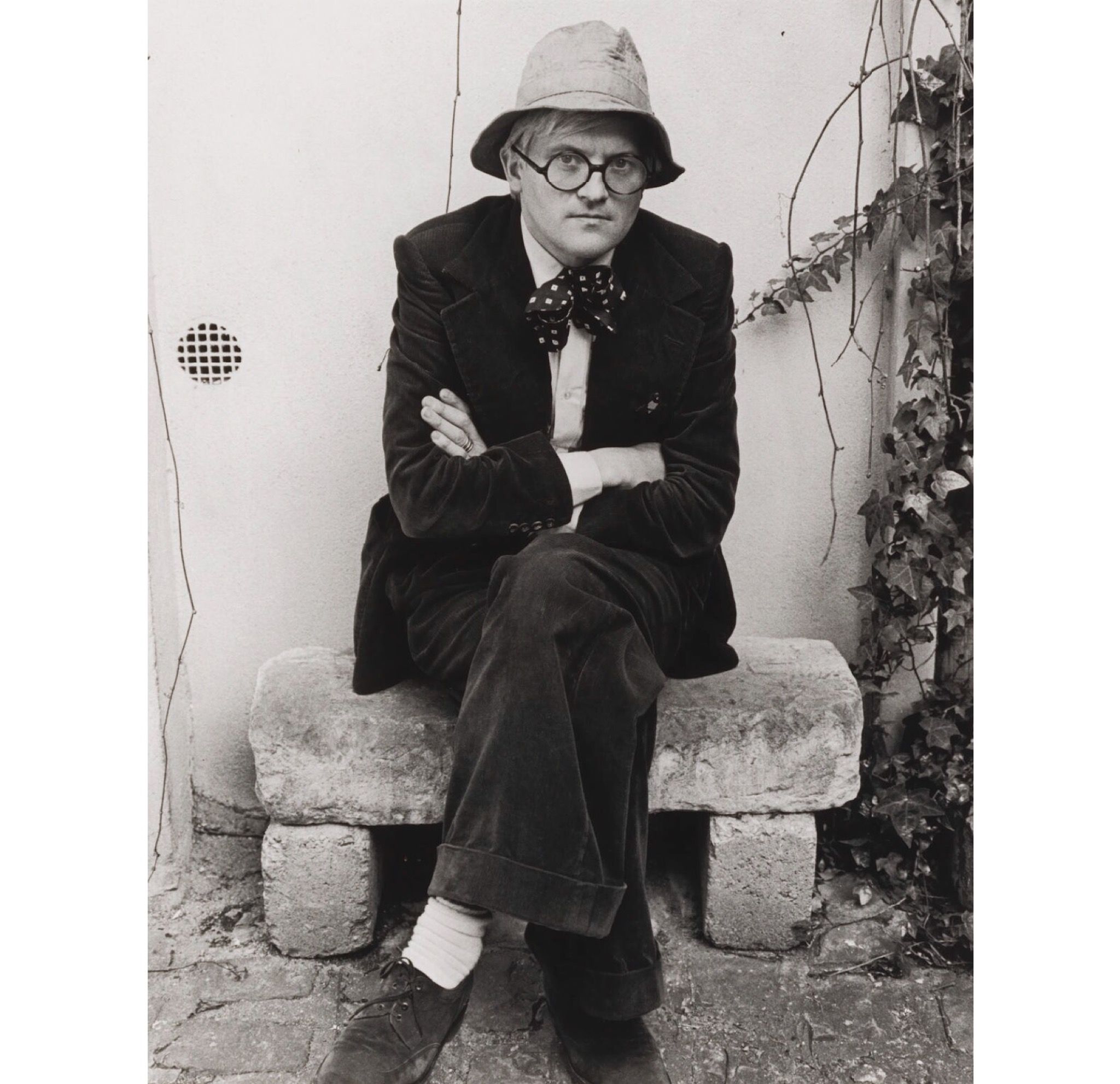

Even people who weren’t painting enthusiasts knew who David Hockney was by the end of the 1960s – at the very latest. How have you dealt with more than 50 years of fame?

The desire for one’s work to be seen by as many people as possible beats in the hearts of even the most modest artists, because art has to do with sharing. I wouldn’t be an artist if I didn’t want to share my perceptions and thoughts with others. But I am not one who secretly enjoys having his private concerns dragged into the spotlight. My paintings belong in public, but I don’t.

In 1990, you refused to be knighted in your home country because you didn’t want to be known as “Sir Somebody,” as you put it back then. What would you do if the Royal Palace asked you to paint a portrait of Elizabeth II tomorrow?

She’s a remarkable woman – a real test for any portrait painter. I wouldn’t know how to paint a royal person like her. She has majesty, but how does one paint majesty in 2020? If I were to paint the Queen, the picture would be printed in every newspaper. Lucian Freud experienced this hype when he presented HM Queen Elizabeth II in 2001. I think I’ll spare myself a thing like that.

World fame, record attendance at exhibitions, an undisputed reputation among art critics, fortune – you’ve achieved everything artists dream about. Wouldn’t a portrait of your queen be the last great challenge?

Probably yes, but the picture would absorb me for months, and I have something else in mind already. Two years ago, I bought a house near Pont-l’Évêque in Normandy. Since nobody visits me here, I’m three times as productive. For an old man who doesn’t know how much life he has left, every undisturbed working day is a treasure. I’m sick of Los Angeles because smokers are demonized as perverse criminals there. I want to be able to eat and smoke in a restaurant, but if I did, I’d be put in handcuffs in that country. Americans lost their sense of humor; hysteria and repression now dominate there.

How many cigarettes do you smoke a day?

Forty, fifty.

I always keep an emergency reserve of 2,000 cigarettes in the house.

There’s always a carton in my car because you can be stuck in traffic for ages in Los Angeles. It doesn’t matter to me whether I die from a smoking-related illness or from some other illness that has nothing to do with smoking. The reason we die is because we are born. How old was Helmut Schmidt? Ninety-five, ninety-six? I’ve had four doctors in the last forty years. Every one of them was younger than me and warned me that I should stop smoking. None of these gentlemen are still alive! American television claims that British American Tobacco is the greatest mass murderer of our time. What miserable bullshit! The American arms industry deserves this title. Fuck them!

Have you ever quit smoking?

Yes, but after three weeks my assistants wanted to quit because they found me unbearable. So it was smarter to start again. I’m not afraid to die, and I’m curious to know whether it means the end or the beginning of an unknown adventure. Whoever does everything to become as old as possible denies life and is already lying in their coffin. Picasso was still painting at 91, but you can also do it like Balzac. He died at 55 but left behind a work that seems like he had been working on it for 100 years.

There’s a pack of cigarette papers in your studio. Do you also roll cigarettes?

No, I use cigarette papers to roll joints in the evening. Cannabis makes me laugh, and whoever laughs isn’t afraid. That’s why cannabis is healthy.

Will you ever go back to Los Angeles or England?

I’m not sure yet. Traveling has become a real torture for me. I have to be pushed around in a wheelchair at the airport since there are often a number of miles between check-in and the gate. How could mankind allow investors to pervert airports into shopping malls?

You first came to Los Angeles in 1964. Have you ever considered moving to another American city?

I lived in San Francisco at some point, but it was too provincial for me. A city is provincial whenever the locals constantly ask you what you think of their beautiful city. That happens all the time in San Francisco. No one in Los Angeles or New York would ever think of asking you something like that.

One of your most haunting self-portraits shows you as hearing-impaired, holding a hand behind your ear and grimacing. When did your hearing problems start?

When I received my first hearing aid in 1979, I had already lost a fifth of my sense of hearing. Extreme loss of hearing is isolating because you stop going to parties or exhibition openings. You feel cut off from people and withdraw into yourself. After a couple of years, you have that feeling of being trapped inside yourself. I always found it inspiring to go to the opera or classical concerts. Today that would be too depressing for me because I can’t hear the high and low notes. There’s no more music for me without headphones. On top of this, I can’t locate sounds. If a telephone rings, I have no idea which direction the ringing is coming from.

Most of your friends and companions have been dead a long time. Are you lonely?

I figured out quite early that I’d be lonely and loveless at some point. That makes it easier to bear. When I’m struck with melancholy, I go into the studio and try to imagine that it’s my duty to cheer the world up with a new painting. I don’t dare to judge whether painting can change the world, but I do know from my own experience that art can make despair more bearable. Those who are blind to art need to be shaken awake.

You don’t mind being alone?

I get by alright, because I think what goes on inside my head is interesting. In that sense, I’m enough for myself. But that doesn’t mean that I don’t have any longing or desires.

People your age have a tendency toward cultural pessimism. Do you?

I subscribe to the New York Times, the Los Angeles Times, and the Financial Times, but it’s been a while since I cracked them open. I’m sick of how apocalyptic the media’s presentation of the world is. Are times really getting worse? My mother was born in 1900 and died in 1999. She lived through two world wars and experienced what it was like to have German planes drop bombs on your head. She would have given the finger to anyone who said our planet was going rapidly downhill.

Did you vote for or against Boris Johnson and Brexit?

I’ve only voted twice in my life, and that was a long time ago. I haven’t wasted any thought on Brexit, because my mind has been preoccupied with the Bayeux tapestry and questions about spatial perspective. The Bayeux tapestry dates from the second half of the 11th century and marks the beginning of European art. In comparison to this work of wonder, Brexit is a marginal event.

In the bedroom of your first apartment, there was a dresser opposite the bed on which you painted the words “GET UP AND WORK IMMEDIATELY.” How does such a Puritan imperative fit with your image of having been a sex-addicted party animal in London in the Swinging Sixties?

The chest of drawers was the first thing I saw when I opened my eyes in the morning, and I really did get down to work immediately, because the morning was the best time to paint. The newspapers wrote that I was a flamboyant dandy, but in reality I was a highly disciplined worker, even back then. An artist can propagate hedonism in his work, but he can’t live hedonistically. If he did he’d be out of a job.

Do you remember the first time you thought, “I want to be an artist”?

I knew who I was and what I wanted to be when I was 11. I don’t know where I got this self-certainty from, but it meant that I never cared much about the opinions of professors, critics, or curators. My father was an accountant for his entire life, and he was anything but revolutionary, yet even when I was a boy he instilled in me that I should never care about what the neighbors said. In the 1960s, everyone painted abstractly, but I didn’t, because something inside me said that abstract painting would soon come to an end. That I went my own way in my paintings instead of conforming also had to do with my father’s obstinacy.

As with figurative painting, drawing was frowned upon in the 60s. You mastered it early.

I experienced how art schools stopped teaching drawing. It’s an unforgivable mistake, because drawing is one of the prime instincts of humans, like singing or dancing. Every child does it. I covered the edges of my exercise books in cartoons; I drew the faces of the other passengers on the bus on my ticket. When I ran out of paper at home, I drew on the linoleum floor of our kitchen with chalk. My mother’s only comment was, “David, remember to not paint on the wallpaper!” To teach someone to draw is to teach them to see and to cultivate their sensitivity. Drawing intensifies our vision and makes us perceive things that were previously hidden. This discovery of sight is much more pleasurable than just scanning one’s field of vision with dull eyes. A Turner Prize winner once sneered that drawing is as outdated as riding a horse to work. I had this aphorism printed in large letters on a poster and hung it up in my studio. Many years later, I crossed paths with this man. He sheepishly admitted that the horse comparison was juvenile foolishness.

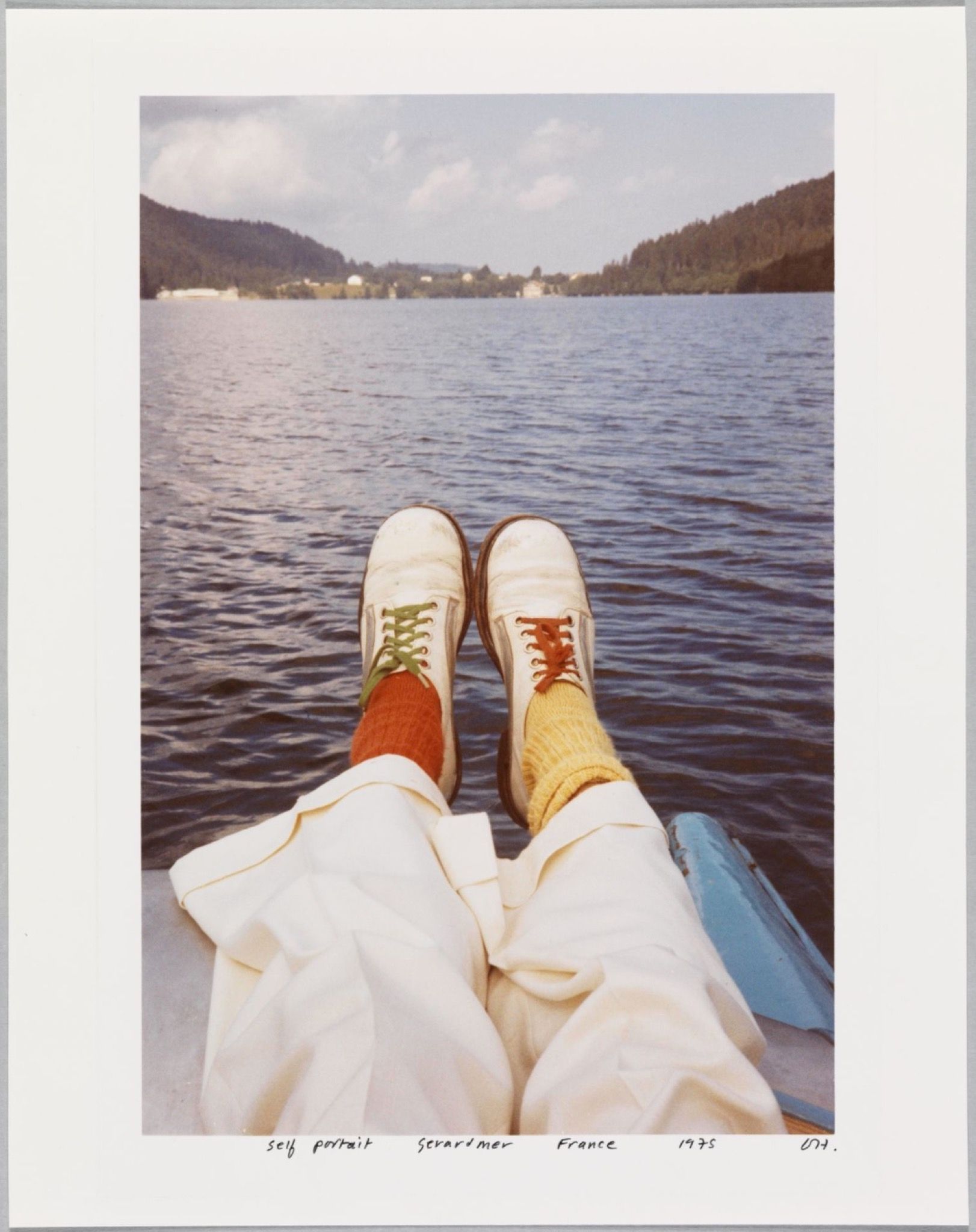

From 2005 to 2013, you lived in an ocean view house in Bridlington, on the northeast coast of England. There you painted still lifes on your iPhone and iPad that were recently published in a book called My Window. What brought you to using your phone to make art?

I bought an iPhone in 2009. At first I mainly used it to watch digital animations of goldfish, but then my sister Margaret showed me the Brushes app. It was the discovery of a new artistic medium.

What did you paint on your screen?

When I woke up, I painted flowers with my thumb and emailed them to 20 friends. It’s so nice to get fresh flowers in the morning, especially ones that will last. After a couple of weeks, I also started painting details from landscapes and the sunrises over the sea. I discovered how I could vary the thickness of the lines and how I could create color gradients. I missed the resistance of the paper in the first few weeks, but the iPhone made me bold because I could correct mistakes without any problems. A watercolor, on the other hand, does not forgive you for the slightest mistake. With the illuminated screen, I could paint early in the morning without artificial light, and I didn’t even have to leave my bed to get the brushes and paints. If I wanted to paint the tiniest detail, I enlarged the corresponding section of the picture with the zoom function. My pictures on the screen didn’t need to dry either.

You bought an iPad in 2010.

Not just one, but a half a dozen. The screen was eight times the size and the pen allowed for greater accuracy and more distinction than my thumb. While I had previously always had a sketchbook with me, now it was the display of my iPad. Artists like Van Gogh, William Turner, or Picasso would have been thrilled with an iPad. The color palette allows for infinite variations, and when you paint outdoors, you can react to every change in the light with a new shade of color within seconds. What amazed me was that you could watch the painting process from the first primer to the last splash as a video with a click of a button, line by line, layer by layer. It was the first time I had ever watched myself paint. My mind is a fraction of a second ahead of my brush – that’s why I never knew how I actually painted until then. Now that I’ve studied these videos, I paint more economically.

The 120 still lifes in My Window show the view from your bedroom window, and sunflowers, orchids, pink roses, snow-covered branches –

You’re missing the fucked-upness of the world in my paintings? I feel responsible for the passing of the seasons and not for Brexit. Or take the glimmer of the first light of day that opens the world: if you have lazy eyes, all you do is shrug your shoulders. But I see in this shimmer a magnificent spectacle with constantly changing subtleties.

In 2010, you were the first renowned artist to have a major exhibition showing iPhone and iPad images exclusively. Did it surprise you that none of your younger colleagues came up with this idea?

No, because certain technological inventions immediately fire my imagination. That started in the 1980s, when I used the computer, Polaroids, video camer- as, Adobe Photoshop, laser printers, and fax machines for my work. In 1989, I had an exhibition in Brazil that consisted only of pictures that I had faxed in. To look at the world through a single lens for my entire life would make it lose its charm, and it would seem like a long death. To see in a new way with technological inventions means to get to know a new way of feeling. For me, that makes the world enchanting once more, since what had once been certain no longer applies. It is the refusal to copy yourself that drives you forward as an artist. I want to show something in my pictures as if it were being looked at with big eyes for the first time. How can you surprise others if you can no longer be surprised yourself?

How old do you feel?

In the studio, I’m 30. When I leave it I feel like I’m 83, grouchy and plagued by aches and pains. This discrepancy also pushes me into the studio every morning. If I were to lose the ability to paint, I’d probably kill myself, just like my friend R. B. Kitaj did. He had Parkinson’s. The most painful nightmare for a painter is that his hands start shaking. That would be the end of him.

How will you know when it’s time to stop painting?

I get the impression that most old people die of boredom. Goose bumps and tears of joy are just words to them. Their curiosity has faded, and the empty routines of their everyday lives lead to weariness and desolation. I still want to be surprised and make discoveries, because I think the world is beautiful and exciting and mysterious. I’ve been painting since childhood, but I still don’t know what my brush will do in the next second. The day that I no longer feel curious in front of a canvas will be the day that I’ll make myself retire. Until then, I’m still excited about the arrival of spring. Like Frank sang, “I did it my way.”

Credits

- Interview: Sven Michaelsen

Related Content

SPRÜTH MAGERS: The Art Gallery and the World

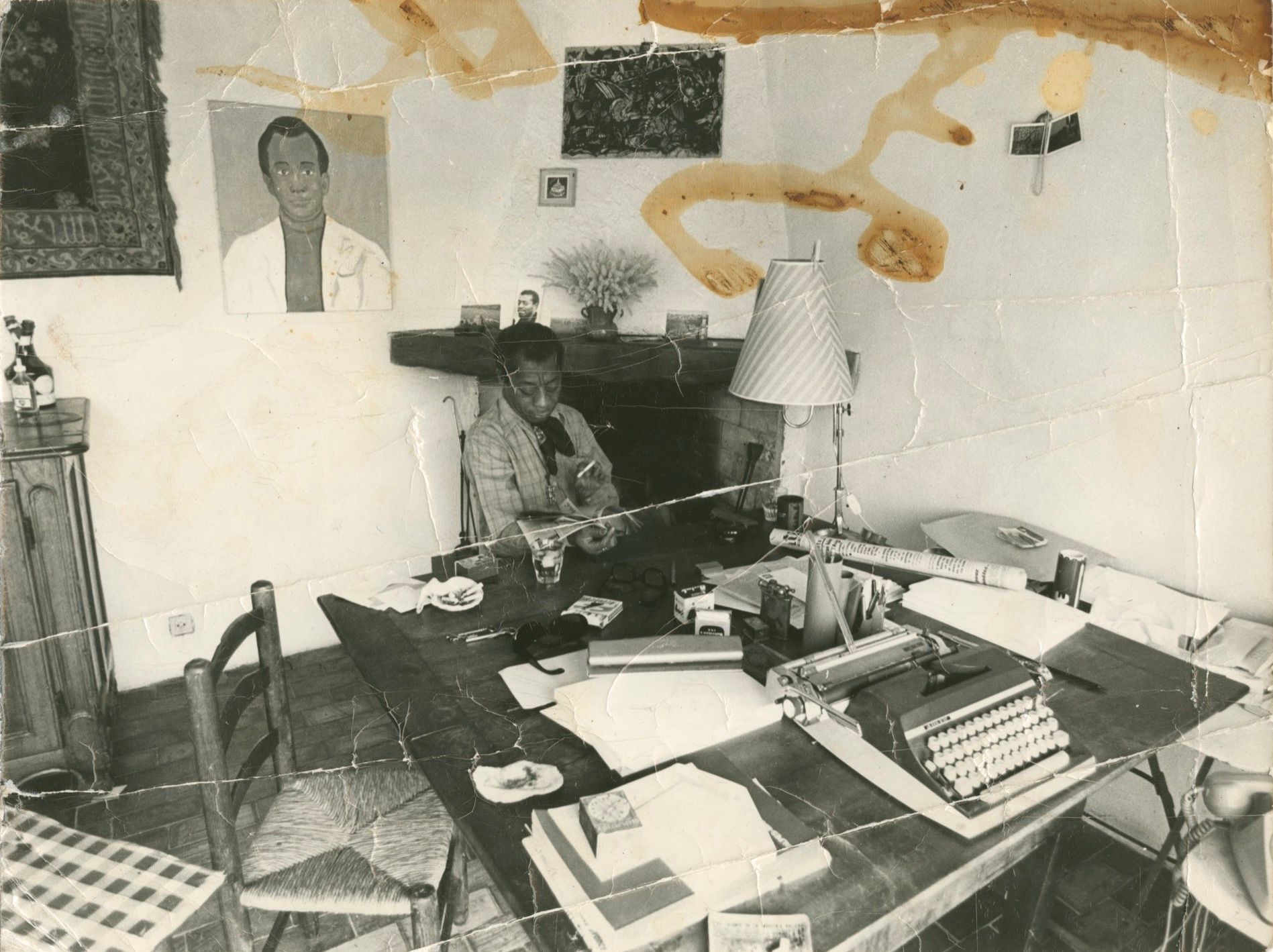

House as Archive: James Baldwin’s Provençal Home

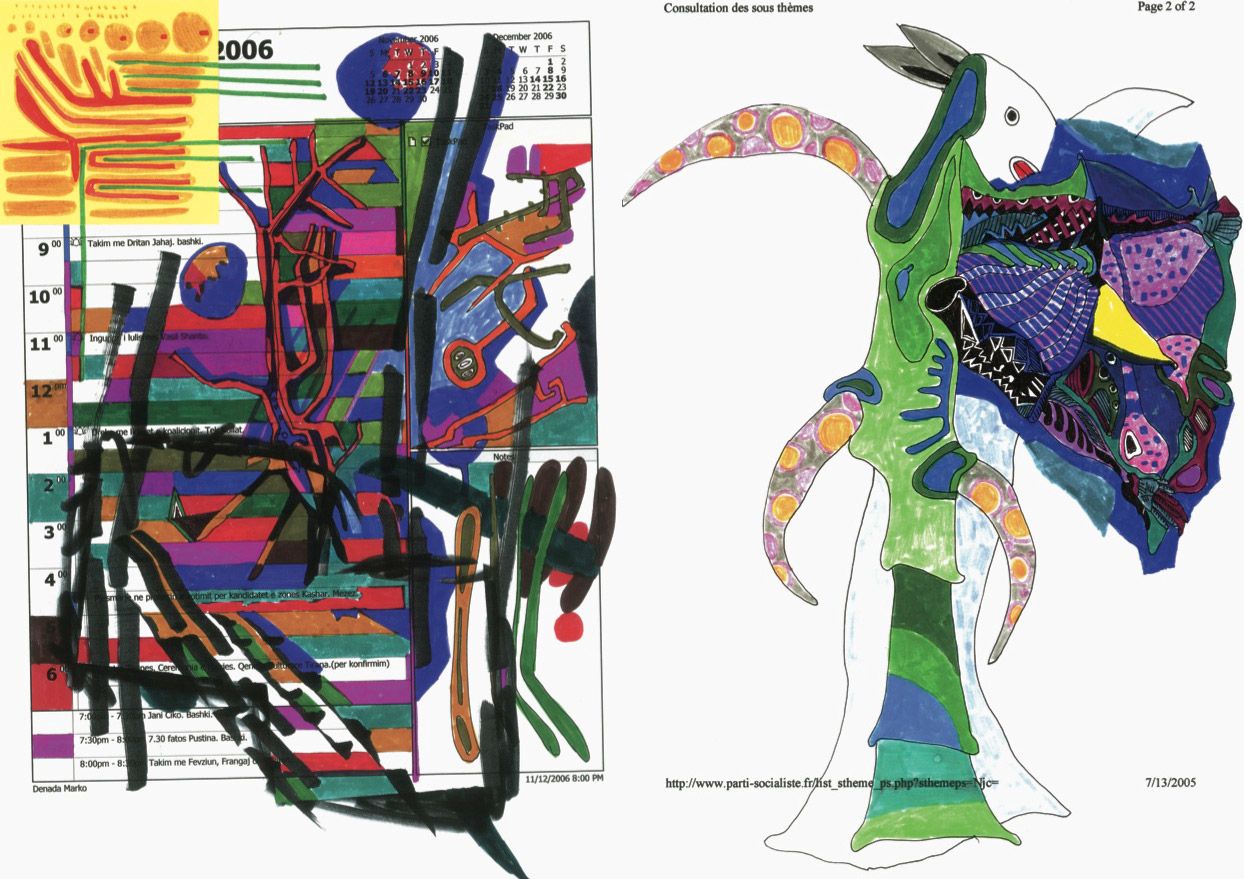

More Politicians Should Be Artists / More Artists Should Be Political: Take Note from Albanian Prime Minister EDI RAMA

Approaches to the History of Art

Art Under Construction

On Power, Picasso, and American People: An Interview with FAITH RINGGOLD

“Ridiculously Modest” by Chris Dercon

A One-Night Dream: HONEY - SUCKLE COMPANY'S Omnibus at the ICA

THE NEW ANGELES: GIORGIO MORODER on American Gigolo

“Architectural, Not Decorative”: WILSON on MAPPLETHORPE

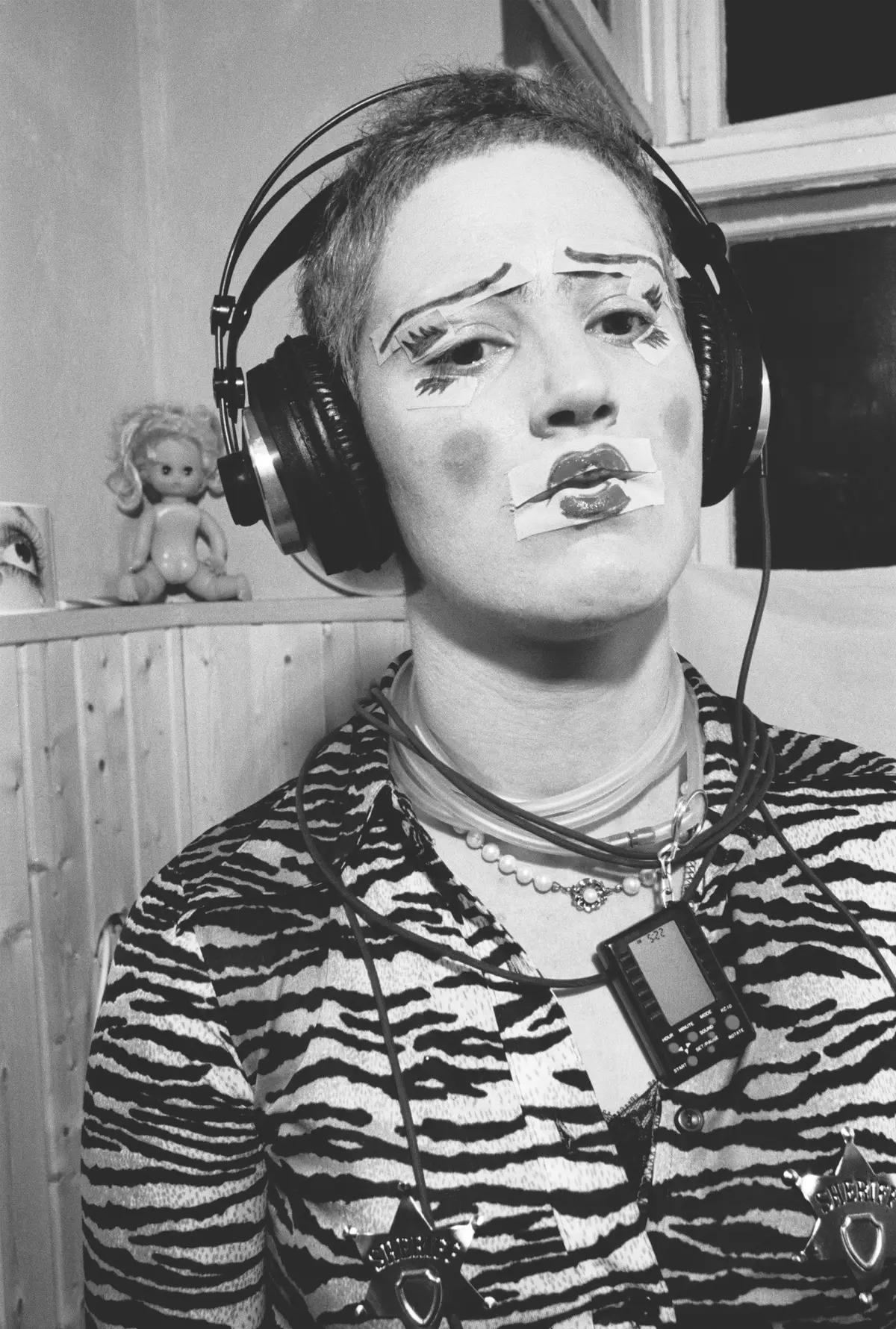

VIRGINIE DESPENTES: Hates People, Loves Dogs.

“It’s Important to Be Visionary Rather Than Reactionary”: Artist Hank Willis Thomas’s Aesthetics of Mass Action