A One-Night Dream: HONEY - SUCKLE COMPANY'S Omnibus at the ICA

|William Alderwick

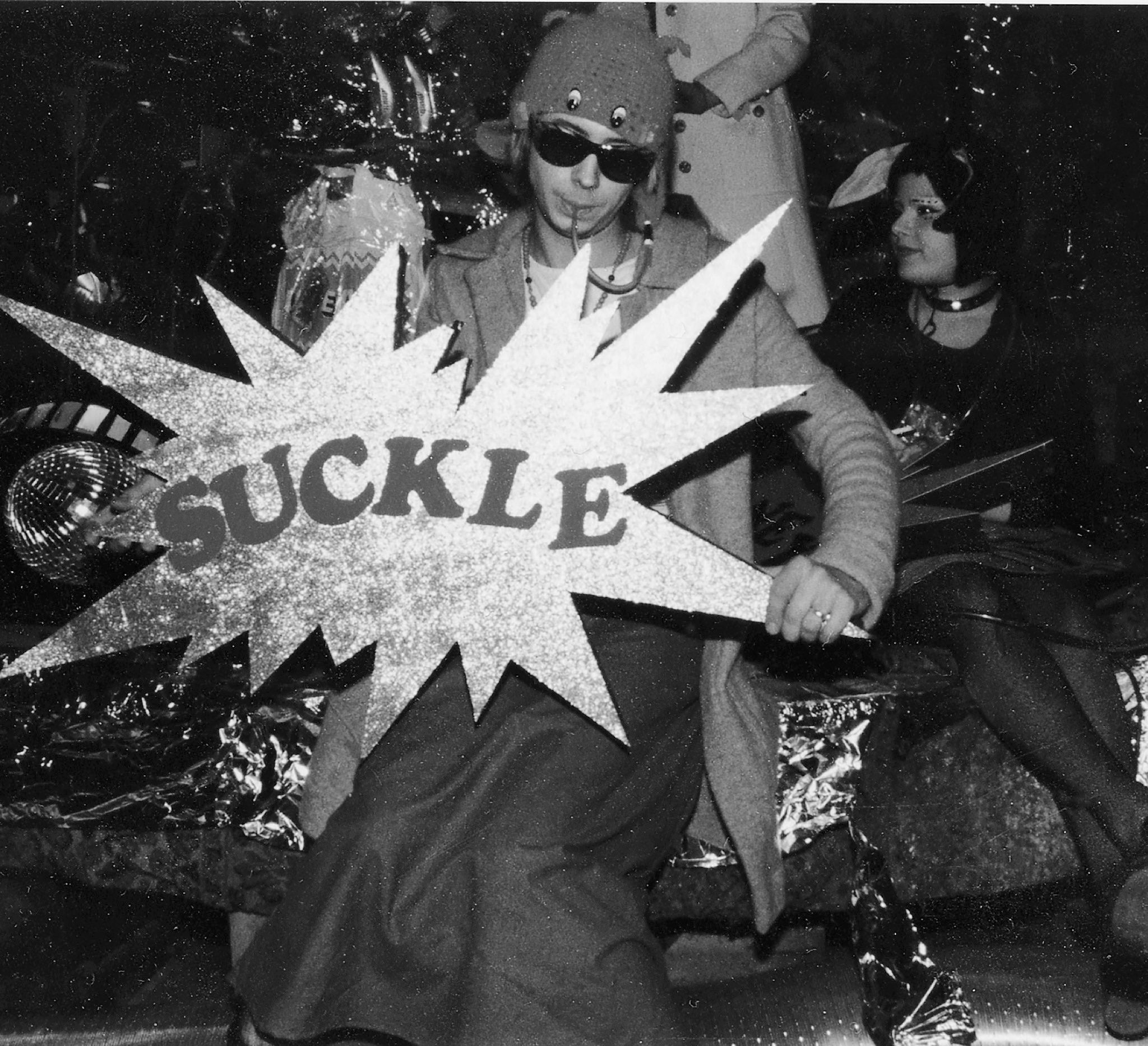

“Fashion is dead.” The Captain Space Sex and Alec Empire flier is pinned up to the wall in the first of three glasses boxes full of photos, fliers, clothing, badges, paint-soaked personal stereos, felt bunny ears, costume fragments, batteries, bits of circuit board, more photos etched with slogans and carved with manga characters, wires and all the eclectic fuzzy, furry, neon dream detritus and documentation from Honey-Suckle Company’s early Berlin art squat party collective lifestyle, on display in their Omnibus survey show at the ICA in London (October 2, 2019 – January 12, 2020). The Berlin collective formed in 1994, just five years after the fall of the wall, in a city obsessed with techno and full of derelict buildings, taking their name from the flower’s homeopathic qualities: helping one to learn from past experience and re-establish a sense of trust in the future, in order to feel grounded in the present.

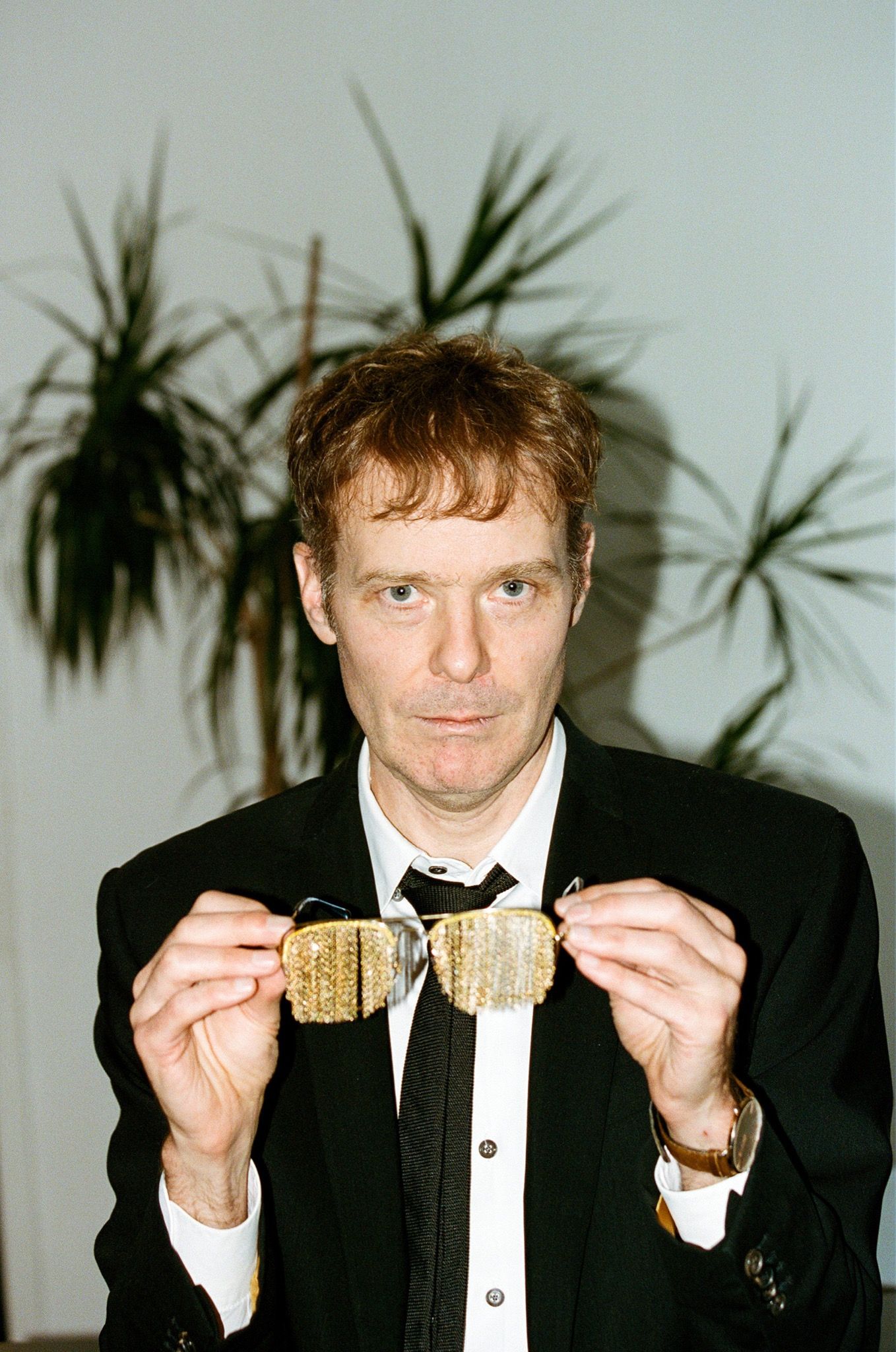

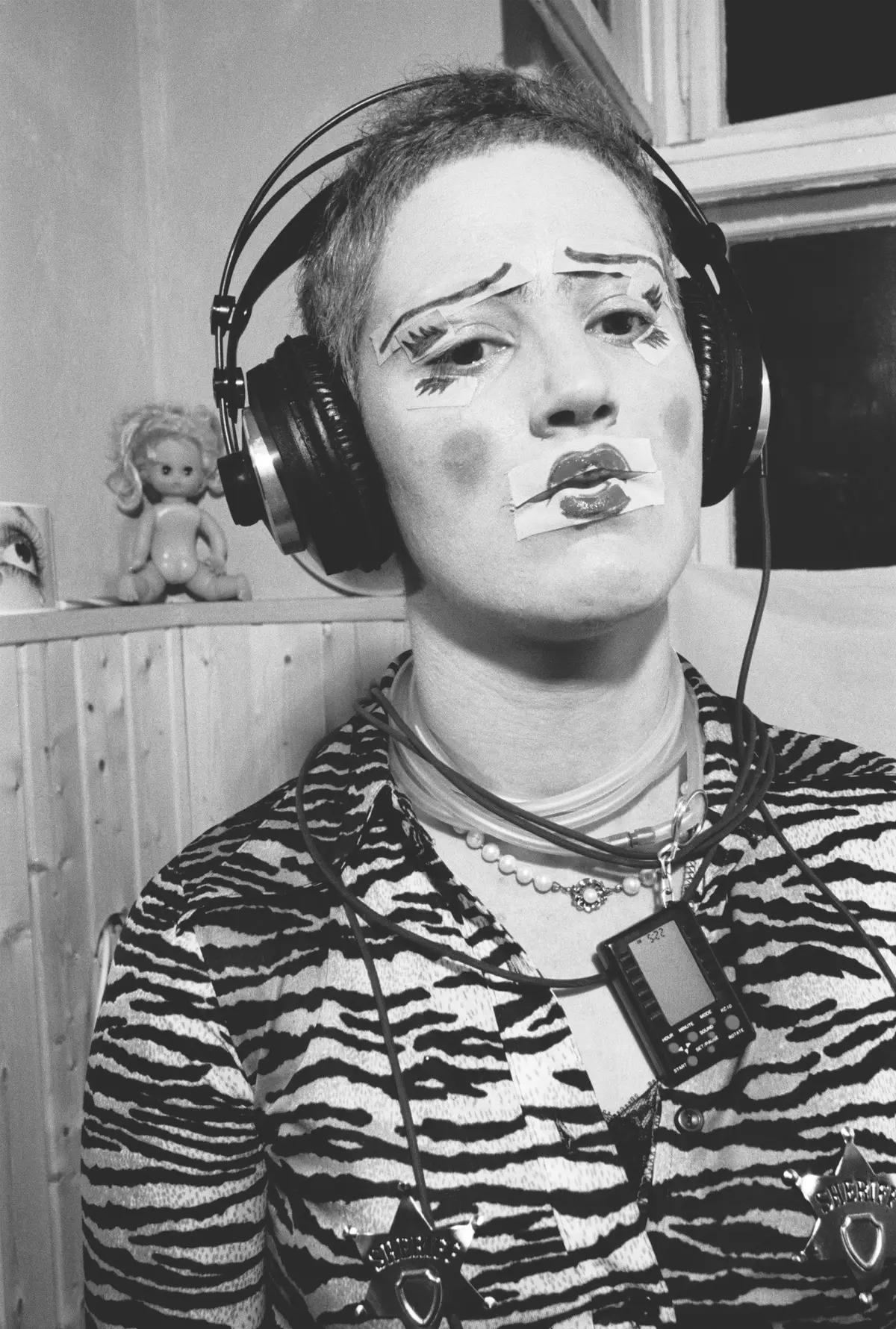

The members of Honey-Suckle Company coalesced around each other, living and working in shared spaces, exploring identity and collectivity through style, producing a series of clothing collections and fashion interventions in the early 1990s that were presented in self-run spaces like berlintokyo as performances, installations, happenings, films.

“Everything was a one-night dream,” said member Peter Kišur at the press view on Tuesday morning. Costumes and outfits thrown together, improvised together one night, out of whatever was to hand, for an unrehearsed performance the next.

Costumed mannequins loiter around on black and white faux-tiled lino flooring, lined by pink walls that recall some 50s kitchenette dream or dive bar, partitioned like a public toilet. Tucked away in one corner, a shoe box on the floor contains a Jill Sander receipt, a golden heart, and a dead rat. Cabbage patch kids and other dolls are strewn on a blanket in another corner. A child-sized mannequin in a plastic raincoat worn over a sports jacket taped with slogans of personal empowerment, and action figure toys positioned on its feet like alternative footwear options. A Chanel double-C logo pin pops out on one jacket, but it’s shorn or vacant somehow, stripped of its potency and aura, as if misplaced like a relic from another world found wandering charity shops at the end of the universe.

Through these early collections, Honey-Suckle Company were working to “destroy the illusion of ego,” explained Kišur. The show doesn’t contain or attempt to show all of Honey-Suckle Company’s collections, clothing, or slogan-taped outfits from this time. Instead it’s a like a series of mood boards breaking down the piecemeal crazed magpie assemblage producing them. “We’re sharing the method of taking identity back,” Kišur continued. The recent climate strikes brought members to tears, seeing a new generation of young activists now discovering and utilizing these techniques of self-expression, empowerment, and protest for themselves.

Against the back wall a stack of television screens radiates with the late-80s/early-90s nuclear waste hues of VHS taped Captain Space Sex performances and films. The churning organic rhythms, melding and mixing as they play over the top of each other, contrast sharply with the monotonous automatic sounds coming from the front hall behind me. This feels human, and full of life. But a sense of nostalgia and absence pervades, nonetheless. The happening is but a trace.

The floor of the ICA adjacent to the front hall is submerged under sand and broken rocks, turned into a dirt pit stage for the end times. Under a spinning wheel throwing flickering colors on the walls, a piece titled NEUBAND comprises a band of mannequins decked out in geometric and bulbous costumes, standing tall and haunting their instruments. An uncertain tremolo echoes the hall from two small electric fans fixed up to hit a guitar’s open strings, taking turns to shift the oscillating tones up or down. Drones whirr almost laconically from a creaking accordion, its bellows breathless like an antiquated artificial lung, as an arrhythmic aphasic bass drum punctures the buzz with an intermittent, slow beat. In the sand a hollow plastic bubble hovers. The collective used to perform in these on stage, but this one is empty now, like a placeholder for something to come or that was never really there. This gloriously happening past, fixed uncertainly in homage.

As ICA’s Chief Curator Richard Birkett noted, Omnibus re-frames and re-stages moments from the collective’s long history together. There is a temporality here that echoes the Institute’s previous show with Black Quantum Futurism, an ongoing concern with our fallenness, the facticities we find ourselves always already thrown within, and strategies for subverting or unpicking them.

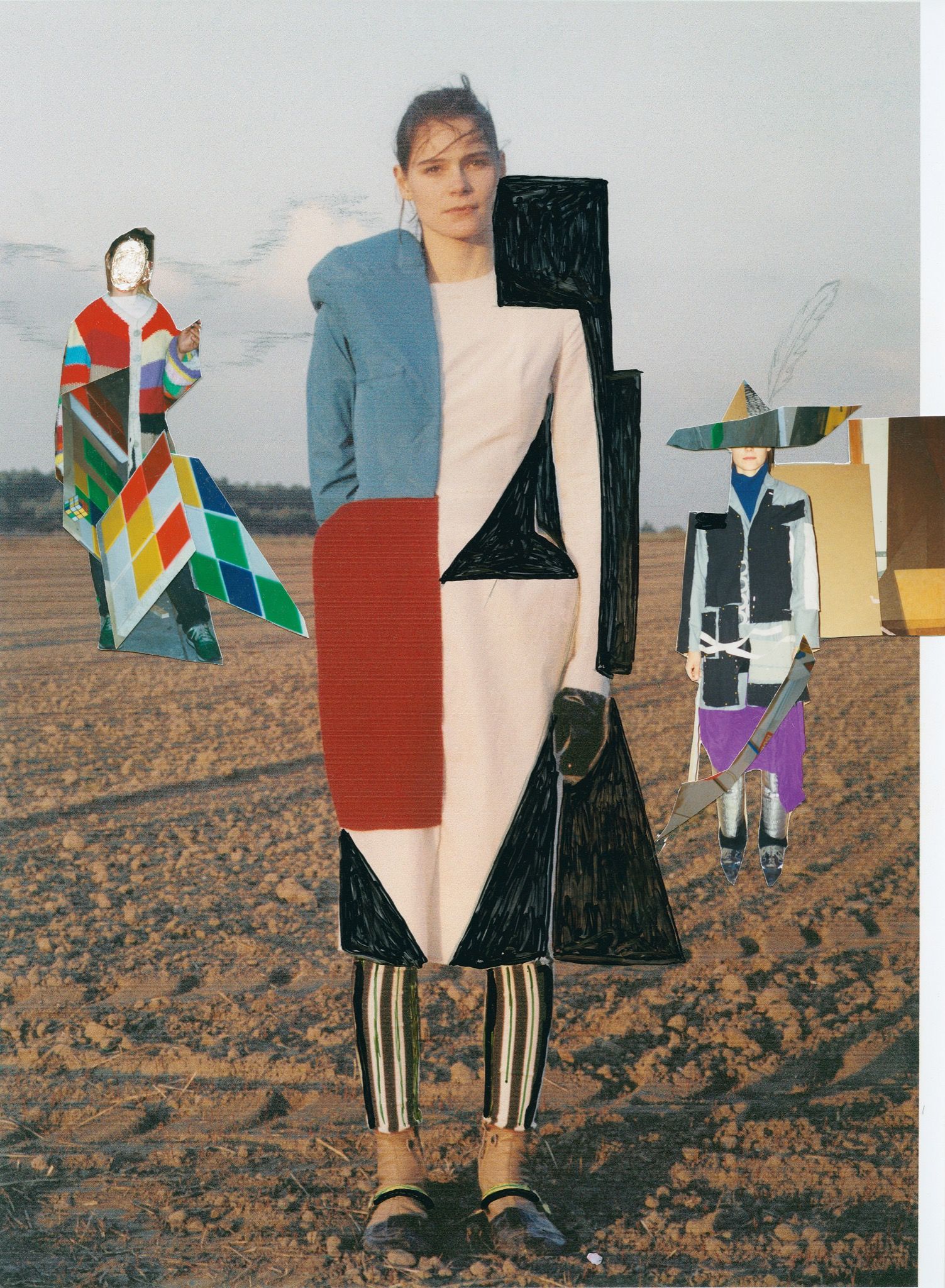

As if moving from the rigid formalism of a Berlin so straight that “techno record sleeves only featured words and numbers, no images,” or that “guitars appearing in the Love Parade almost caused riots,” the collective took their cultural inheritances seriously and to task. The ODESSAU series of analogue photographs and films documents Honey-Suckle Company adopting Bauhaus compositions and forms, re-enacting the “good design” and attempting to reconstruct the human into something new or more, only to pull it apart at the seams; putting on a logic only to then break it, like trying on a new jumper before disposing of it and moving on.

As appropriate for a shifting collective whose membership has changed and evolved over the years, Omnibus takes you into distinct worlds, phases, chapters, and moods of the Honey-Suckle Company journey. How to address or comment on the journey of this collective, this community, over 25 years, both insularly themselves and reflecting the wholes all around?

While interviewing author Virginie Despentes in 032c issue #36, writer Helene Hegemann comments:

“Berlin did everything wrong. Anything was possible in the 1990s. Berlin was a wasteland, new and old at the same time. It could have become the ultimate utopia. Imagine being a teenager in the 90s in Berlin. You’re 14 or 15, you start going out and you start falling in love, and you start to conquer the city you were born in. And suddenly the wall comes down and the city gets bigger. I imagine this as one of the greatest experiences you could have as a teenager. And they could have built something out of that experience. But what happened is that Berlin became a cheap fake of thirty other cities. Berlin had the potential to become a city unlike any other. Now this possibility is completely gone. Well, not completely. But almost.”

Honey-Suckle Company’s journey runs alongside and within the arc Hegemann describes, from stylistic self-expression and experimenting with collective living and action, to exploring, integrating, and ultimately rejecting cultural hand-me-downs, whether fashion, music, art, or theory. In this vast open vacuum of a city where anything goes, its members sought grounding in the collective.

Upstairs at the ICA, an eerie automated trio of mechanical harps turning slowly (on donor kebab motors) greets you like a demented child’s music box. It’s unsettling at first, untuned and discordant, but as the wheels turn a simple scale progression emerges, pulling each scratched and imperfectly sounded string together, to resolve and reset with a twinkled flattening chime. Uneasy, yet grounded.

Omnibus continues on either side of the group’s most recent work, RAINBOW PRESS PAGE 4, a parodic dance hologram projected like ghostly nymphs in miniature above a ceramic vase. To the right, OHN END and NON EST HIC (reconfigured and combined for the ICA installation) grab your attention before you enter the room with a sound like a cat’s mew. Thin colored sheets of fabric hang from the ceiling, flowing through the center of the room, carving the space into loose, discreet pockets, like a tent. Indiscernible layered voices chirp out from all around, and two sets of metal stairs float in the folds of fabric over your head, a stairway into the heavens, loftily out of reach. As ethereal as clouds, and upwardly lifting as your attention scans vainly in search of the sources of the voices and the sounds, the piece suggests mysterious spaces hidden above.

Photos line the walls from the EAUDE series, showing bodies entwined together, faces covered, twisted up in sheets and merging through tangled hairs. A response to the lebensreform back-to-nature movements, these multi-limbed organisms contort their way through woods and fields, like detoxified and desexualized holistic counterparts to the Chapman brothers’ Zygotic Acceleration sculptures.

On the left, MATERIA PRIMA. Crouching, you step through an entrance cut into plasterboard and a wooden frame, and out into the perfect white expanses of an edgeless room. This freshly painted curve seamlessly encompasses the walls and floor. Alone in the horizonless space, looking downwards, there are infinities to bathe in; like a cut-price James Turrell, all the bang for half the bucks. It is a void, the complete absence of visual information. According to Honey-Suckle Company, it’s a space of detox and reset, offering a caesura restart oneself from. But the artifice of this space remains present. Looking up, the exposed and unconcealed cornicing of the room’s ceiling and lighting fix us back to reality — reflecting an opposing movement to OHN END and NON EST HIC’s heavenly mysteries across the hallway.

In her introductory remarks, Helene Hegemann references Bini Adamczak’s Beziehungsweise Revolution: 1917, 1968 und kommende: the past century’s revolutions, Adamczak argues, were both of the state (Bolshevik, 1917) and of the individual (May ’68). The revolution to come will be one of relations, the inter-personal — one of collectives even. There are two meanings of Omnibus: as a collection of previously separate or distinct entities, typically periodicals, and the Latin origin, for all from all. The arc we might read through Omnibus moves through twenty-five years of taking hold of the body to leaving it behind in new configurations, dimensions, and relations. Perhaps the revelations proffered in collective action that their work suggest is the stuff of revolutionary potential. Whatever is becoming of the city of Berlin now, Honey-Suckle Company’s pursuit of something else in collective experience and action, of some potential, of some kind of “ultimate utopia,” whatever that may mean, promises us new cartographies, strategies, and techniques for reforging our relationships with ourselves and with each other.

Credits

- Text: William Alderwick