Strange Bedfellow: An Ode to the Outsider with SOUFIANE ABABRI

|Victoria Camblin

“What would you have me do?

Seek for the patronage of some great man,

And like a creeping vine on a tall tree

Crawl upward, where I cannot stand alone?

No, thank you!”

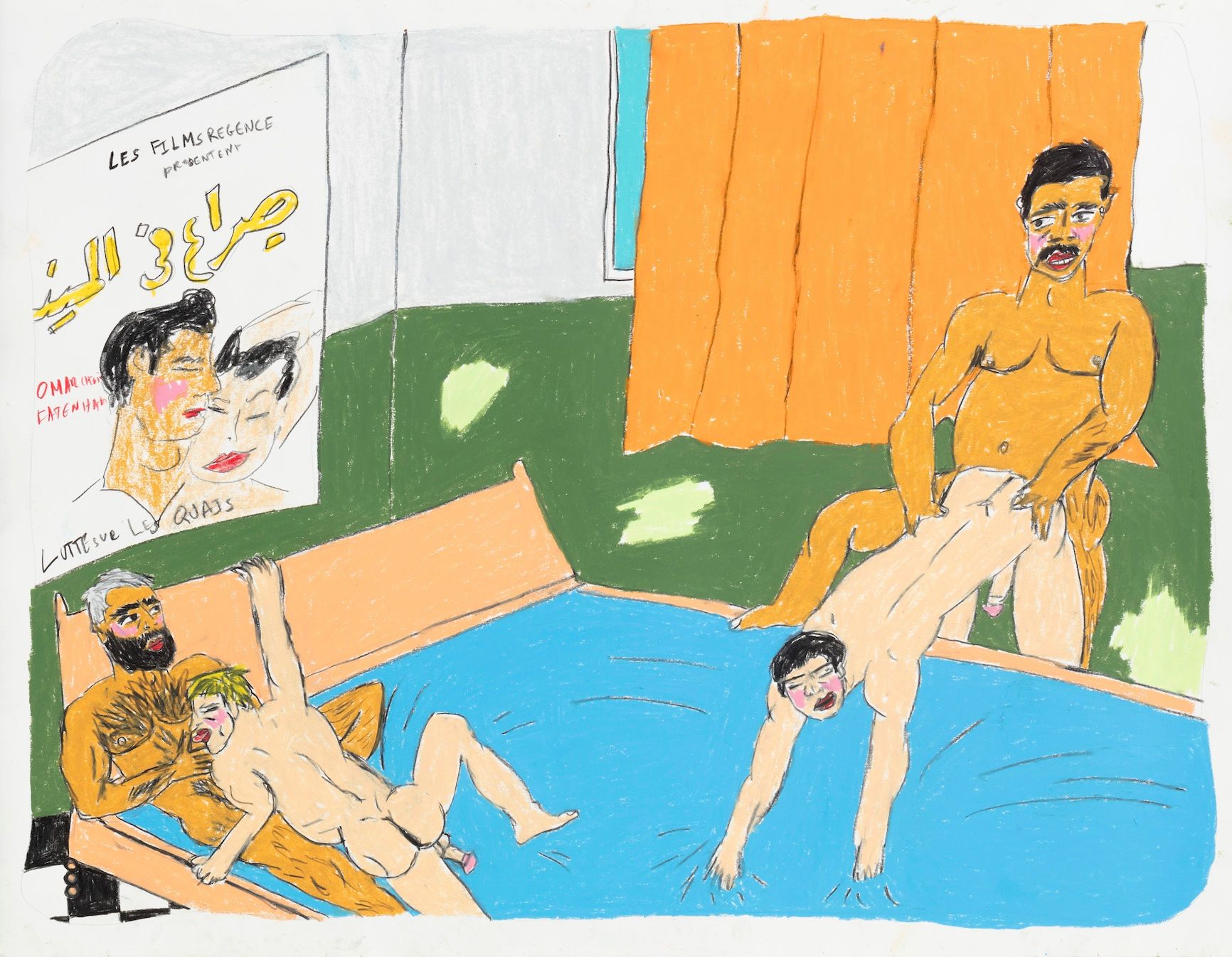

So begins the famous “No Thank You” monologue in Edmond Rostand’s 1897 Cyrano de Bergerac. A real-life version of the play’s titular character, fictionalized as a libertine-swordsman known for his sharp prose and enormous nose, lived in France in the 1600s, during the Thirty Years War and the reign of Louis XIV, in an era of flourishing in French art and literature thanks in large part to aristocratic patronage. Noblemen and kings sponsored writers, who in turn flattered their benefactors in their works — a model that de Bergerac, in Rostand’s interpretation, eloquently rejects with a non merci. The 17th century also gave birth to the Académie Française, an institution dedicated to the regulation of both the playwright and his protagonist’s weapon of choice: the major cultural asset that is the French language. Perennially criticized for its conservatism and notoriously opposed to regional idioms, this national authority was dissolved during the French Revolution and reinstated in the early 1800s under Napoleon Bonaparte. When Rostand was inducted a century later, in 1901, he became its youngest-ever member. Yet his Cyrano reveals an institutional skepticism, expressed from within the academy itself. The piece made critics uncomfortable with its admixture of vulgarity and virtuosity, and its poet-hero who scorns the model to which all artists are bound.

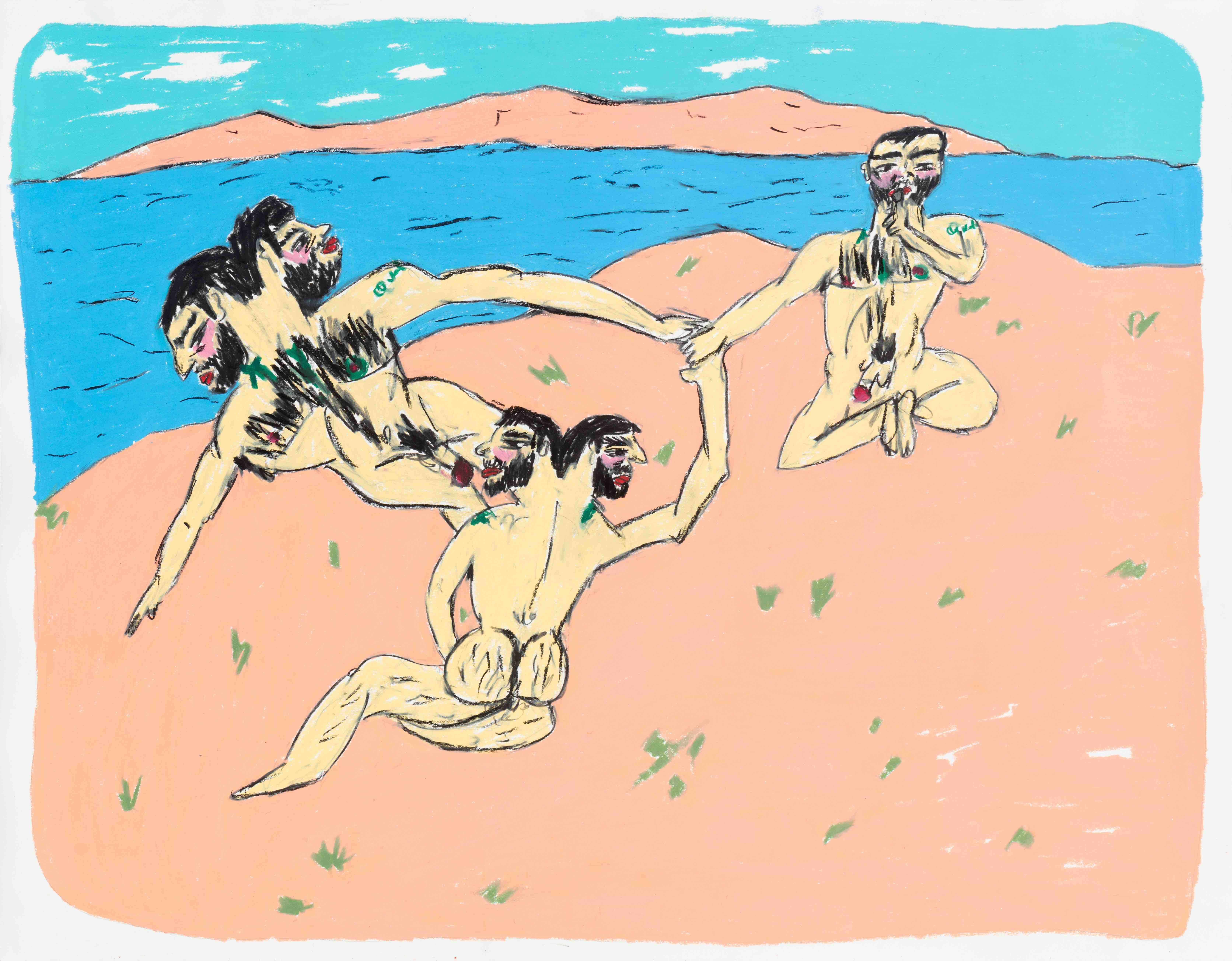

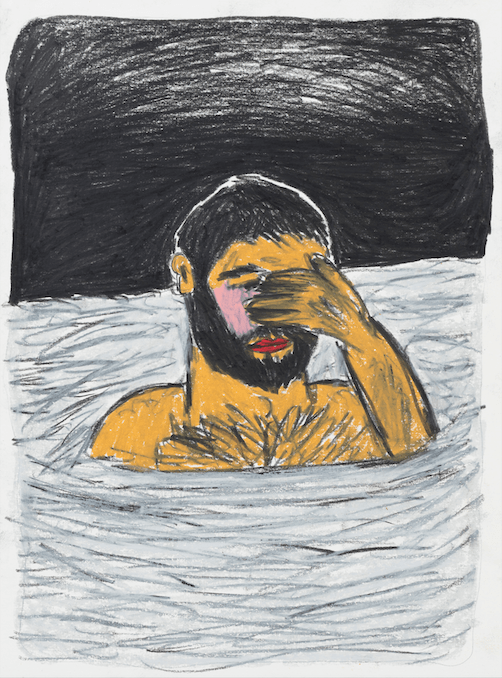

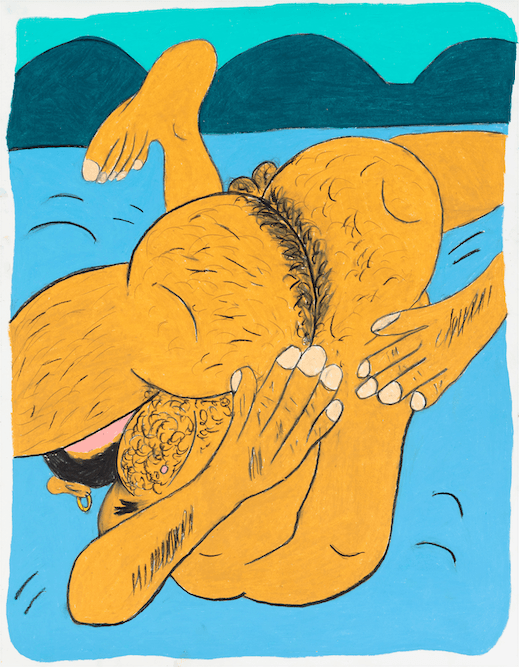

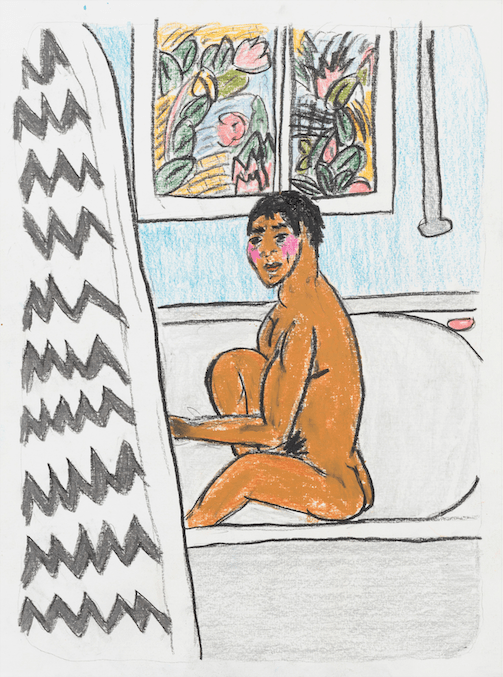

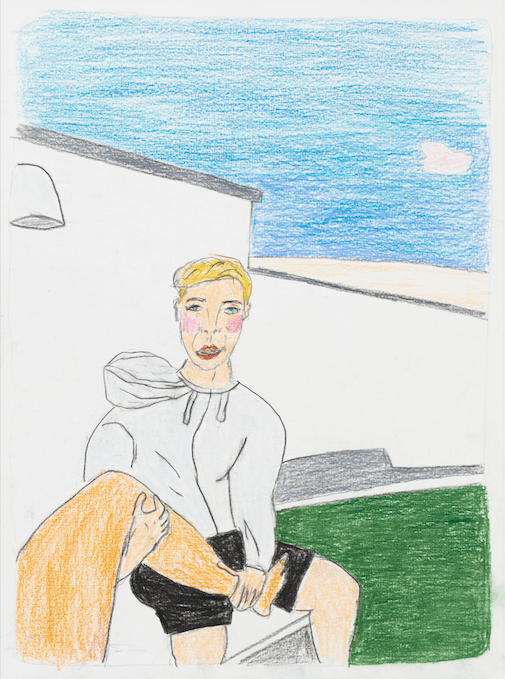

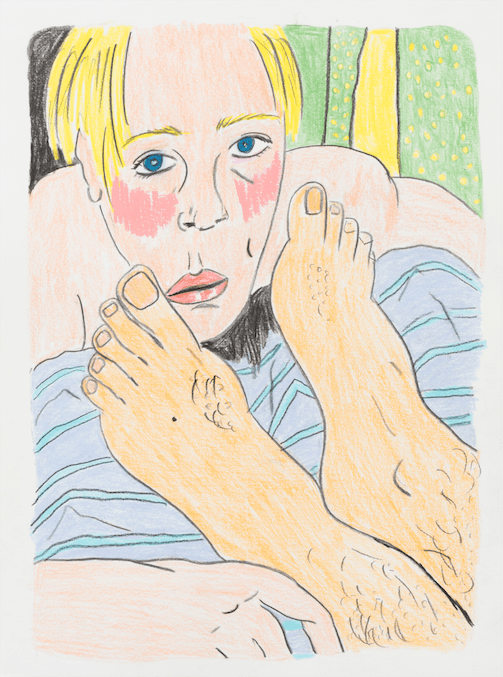

Rostand would not be the last French-language author to battle this mother tongue. In the 20th century, Jean Genet (1910-1986) emerged as a notable “enemy from within” the literary establishment, who waged a “war of words” against the same canon he would come to inhabit. “I couldn’t change the world alone, I could only pervert it,” the vagabond-turned-author wrote of his purposeful deviations. “[T]hat is what I attempted by a corruption of language, that is to say from within this French language that appears so noble.“ Both Rostand and Genet feature as main characters — and creative forebears — in the artistic practice of Soufiane Ababri, whose exhibition “Non Merci!!,“ named for Cyrano’s tirade, now enters its final week on view at Berlin’s Dittrich & Schlechtriem gallery. Ababri maintains a studio in Tangiers and a practice both literally and atmospherically “between” Morocco and France, creating in the queer and decolonial margins that flank the realms of critical theory and French literature, sociology and political activism. In "Non Merci!!!" his investigations take form as a scenographic installation, which was animated by performers on the opening night and remains populated by a new series of Ababri’s “bedworks”: drawings in colored pencil on paper made, as their name implies, in bed. The result is a play of inner and external experience that speaks at once intimately — artist to community, and artist to self — and publicly, querying the status quo.

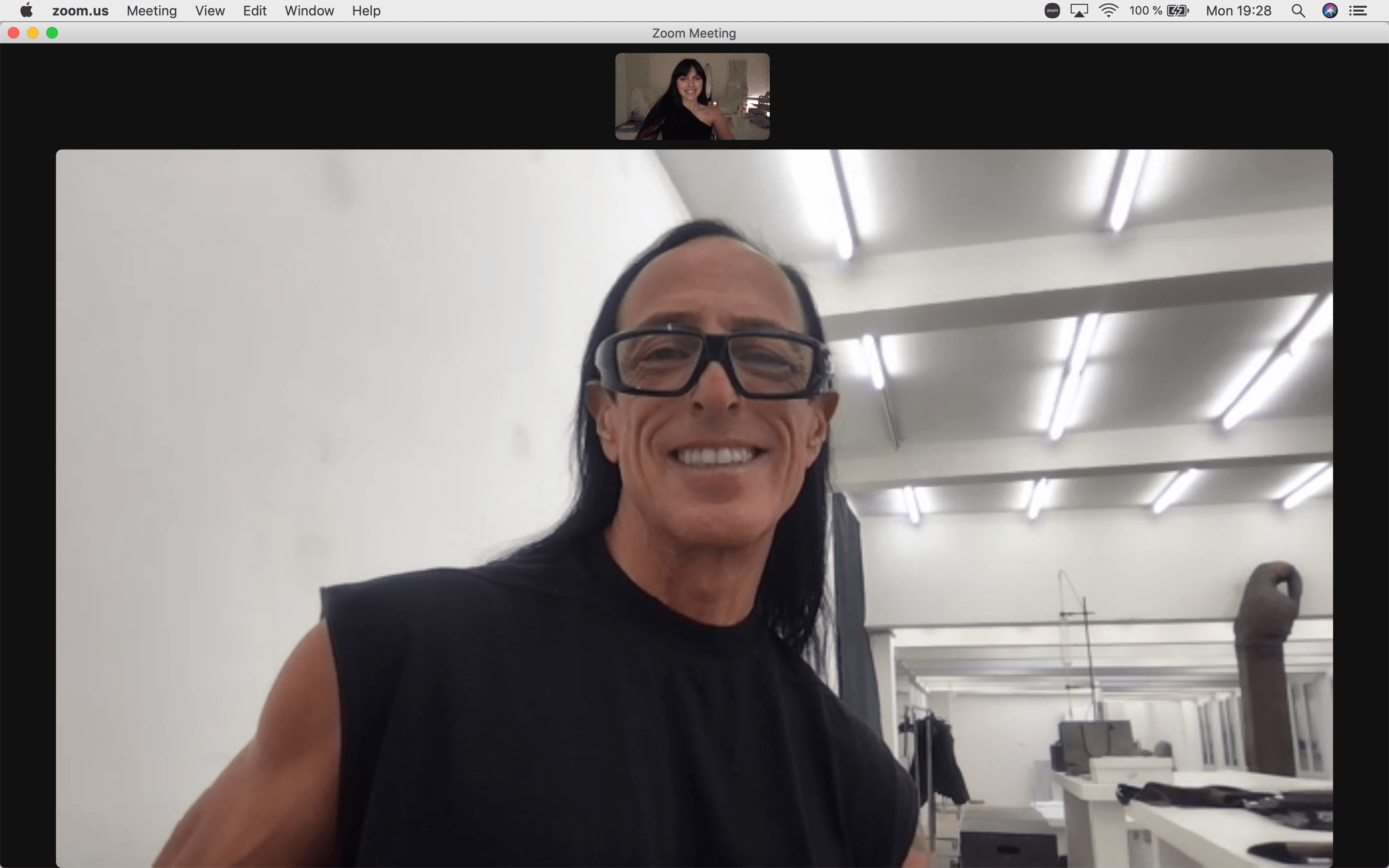

Victoria Camblin: How did you find Berlin while you were here for the show?

Soufiane Ababri: I love that city. It’s my second time showing with Dittrich & Schlechtriem, and I’ve found that there is an energy in Berlin that really pushes the performative side of my work. You need the right exterior energy to access a certain level of work, and that often comes from the people that surround you. Working with Andre [Schlechtriem], there is something that happens where he takes a project somehow above and beyond where it started – it’s an exchange that pushes me to exceed myself, to do things that would otherwise have just been murmurs in my head. That’s what I expect from a gallery, or from any institution: to help realize small miracles. There is a critical moment at the beginning of any project where you have to find the means to make it physical, real – to materialize it. My experience in Berlin in that respect has been sublime.

VC: You mentioned it being particularly inspiring for performance. How would you describe the interplay between that and your drawings – between your two-dimensional works and your “live” activations in space?

SA: The drawings are really something I do without anyone seeing me, in domestic space. I don’t even draw in the studio, where people are maybe stopping by for a visit, but really in personal space, in a “safe space.” I enter a dialogue with people with everything that is “exterior,” which includes scenography as well as performance – because I never hang anything on white walls. I want to put something immersive into place, where there aren’t just drawings made between myself and the medium, or between artist and output. I want to engulf everything that’s in a space, to give it an energy and try to relate to everyone present. That’s when the body starts to play all the elements inside the drawings.

VC: It's interesting that you use the theatrical term “scenography,” as opposed to décor or interior design. I think historically it was more common for artists to do set design, and for visual arts to cross over into dramatic ones. In France in the 20th century, with dadaism and surrealism, you had avant-garde artists creating work explicitly for the stage, designing backdrops and wardrobes. It seems more siloed now.

SA: I’ve never formally worked in theatre, but I do have, let’s say, a political and cerebral conception of theatre. I invoke it in my exhibitions. Cyrano de Bergerac, which is the reference for this show, is obviously a piece for theatre. Maybe one day I’ll intervene in the context of theater, doing scenography for someone. I certainly have desires.

VC: Now I’m fantasizing about you doing the set design for a production of some classic French play.

SA: There are artists from another generation who I would say nursed me, as I was growing my practice. I adore Marc Camille Chaimowicz, who uses scenography and decorative arts as a means of expressing a position and transforming it. His work raised me, artistically. With his conceptual approach, his literary references to authors such as Proust, his ability to transform an exhibition space into somewhere to gather, to converse, to read plays together – he really creates. Similarly, there is a side to my work that is scenographic, and another side to it that is about creating warmth. I don’t relate or refer to the “white cube” at all. People who go see the show in Berlin have a lot of things to read and see outside of what I made drawing alone in my room – elements linked to the performance, Cyrano de Bergerac’s “no thank you” tirade written on the walls. There is an aspect of wanting to transport viewers elsewhere.

VC: The Cyrano de Bergerac speech is where you get the title of the show, “Non Merci!!” Your work is often interpreted politically. Would you say there is a theme of refusal there, connecting the work to the politics or social discourse of the moment?

SA: It’s not really “refusal.” Maybe I’d call it “rejection.” It’s about pushing something away, but “no thank you” is a very distinctly French way of doing that. “Non, merci” isn’t just a “no.” You have the “thank you” there, too. It’s a way of being punk or marginal while also being distinguished, which is what Cyrano de Bergerac – who I have always loved – does while still rejecting something. It’s not just about pushing society away. This also happens in the work of Jean Genet. Genet writes in a sublime manner, using the highest form of the French language, but at the same time he rejects that language. It’s a question of rules and order. As artists we can continue to make things, to build something using those existing structures, but at the same time we can “no” to things that prevent us from being subversive, from pushing barriers; to things that asphyxiate.

Rejection is a kind of exchange, in fact. I think that’s what protesters are trying to do when they go out into the street. They’re pushing away a system but it’s not a totally nihilist or anarchist gesture. It’s an attempt to get something back – a “no” that invites a response from the other side. Importantly, this “non merci” is absolutely not addressed at the spectator. Cyrano de Bergerac is waiting on a response, whether it’s one of agreement or disagreement.

VC: You’re touching on traditional forms – of “politesse,” and of language and expression in general – and exploring the possibility of being radical within those structures. It’s the problem of having to reject the oppressor in the oppressor’s own language. In this case, that language is French, which is a language that has been imposed in so many regions across the globe.

SA: Yes. I’ll cite Jean Genet again. Genet writes that marginalized individuals and groups have a different relationship to these systems due to their experience of events such as colonialism, and so on. Of course, Cyrano de Begerac has been translated into every language. I was in a French lycée in Morocco, in Rabat, so I read it in school.

VC: They were very effective using this language and this literary tradition in service of cultural imperialism. It’s explicitly called “the secular mission.”

SA: There are things that I have enjoyed for years and each time I revisit them with a different outlook, re-analyzing and really re-viewing them. I basically know the repartees surrounding the nose, or Cyrano de Bergerac’s “non merci” speech, by heart, and things like that follow you for the rest of your life. Each time I go back, it’s with a different and deviating perspective. I may dive back in from my position as a guy who is gay, or as an immigrant coming from a Muslim tradition and working with a post-colonial approach. I’ve been making these drawings, the “bed works,” for years, and I constantly get remarks from artist colleagues or from gallerists trying to push me toward other things. They’ll ask, “You’re not going to make drawings in bed for the rest of your life, right?” or “you’re not going to keep the prices the same forever, are you?” or “don’t you want to start making sculptures?” At a certain point in your artistic career, these institutions will try to bring you away from a domestic practice, away from a practice that is considered “small.” There has been a sense of minimization around the choice to draw. I returned to Cyrano just at the right time, and there it was: “Non, merci.”

VC: Do you feel like there’s something happening right now with Cyrano de Bergerac, like there’s something in the Zeitgeist? I noticed this work coming up in conversations recently, even before I started thinking about your show, mostly around the premise of identity-swapping and appearance. My theory is that the renewed interest has something to do with ideas of anonymity and creative authorship and how those themes are playing out today, particularly online.

SA: But I wouldn’t say that people are interested in saying “no, thank you” right now. When you look at Lebanon, or at what’s happening in Iran, or in Ukraine, you’re not seeing a lot of the “thank you” part, on a social level. There are very courageous people doing very courageous, very urgent things. They’re not going about this with a literary approach. My practice has a literary approach, which works critically only in the long term. That’s why I say I’m not an activist artist, even though plenty of people would like to consider me that way. I refer to oeuvres that are part of cultural history. My work is connected to a certain community, and in revisiting aspects of culture I am trying to change the way we understand things at their core. But that’s different from what’s happening now, in the reality we live in. It’s not going to have an impact on what’s happening in Iran.

VC: How would you describe the community your work is connected to?

SA: It’s LGBTQ+, it’s de-colonial, it’s racially conscious. I’m talking about and to people who, because of a certain stigma, have been rejected by society. And from that moment of rejection, I consider them to be part of a family, a community.

VC: Getting back into bed, as it were, that’s also a kind of marginalized space. You mentioned you have been making work there for several years.

SA: I started in 2017.

VC: So, it’s not a Covid thing?

SA: No! I had studied in various prestigious art institutions in France, and there was always this view where drawing was marginalized. Drawing didn’t have the same force as video, or installation, or sculpture. It was second rate, preparatory work. This meant that it was always part of a practice that was “outside” the rest of my work, in the sense that I was doing for myself. All artists do things for themselves, things not intended to be exhibited – “projets de tiroir,” as we say. I kept drawing, just as I’d loved to do since I was young, and at a certain point I started to “problematize” it, as we would say in sociology class. Meaning that you observe yourself – or a society – doing something forever and eventually you ask why. Once I started to problematize my relationship to drawing, I wasn’t content with just doing it anymore. I need to have a process with my work, because it’s never going to just be about making things – it has to have this link to social study, to criticism. So, I thought, “what am I doing?” That line of inquiry brought me to the bed works.

VC: Would you say part of it is also revealing and presenting works in progress, rather than finished ones? Like each drawing is part of a larger ongoing research project, not an individual end in itself?

SA: It’s never finished. The bed works form a kind of base that allows me to go in different directions. I always start a project by drawing, and it’s always something that ties my work together. The idea that the “bed works” are going to change? No. They provide a thread that connects everything I’ve done so far and will guide me to other places. Because the bed is something that connects all of us. There’s the orientalist representations discussed by Edward Said, but there’s also AA Bronson’s work about the bed’s rapport with AIDS, for example, and how people were bedridden. It can be a place of rest, of illness, of love, of work. It’s something that exists in some form in every domestic space. It’s inexhaustible as a consideration, really.

VC: There’s a side to it that is representative of a kind of globalism. You even find the same exact beds in different domestic spaces – like if I rent an AirBnB in Tangiers there might be the same Ikea bed there as you would find in an apartment in Berlin. As you note there’s also a strong art historical tradition in its representation as a queer space. I’m thinking of Rob Rauschenberg’s painting, Bed, which is a vertical single bed-sized “canvas” with painted sheets. Cy Twombly drew on the pillow.

SA: They were together, right?

VC: Exactly. You have this heavily painted lower plane – the visceral, bodily fluid-stained part – and then these delicate Twombly drawings at the top, where the head and the dreams and the mind and the subconscious are. It’s also got a link to surrealist dream experimentation, and to psychoanalysis, where you are lying down and laying your thoughts bare. You’ve said drawing is a “safe space” for you. Is the bed one, too?

SA: It’s not at all a “safe space.” I certainly wouldn’t want to summarize it as one, anyway. The bed can also be a place of pain, a place of insanity, a place where people are cloistered day and night because they are in a challenging psychological situation with respect to the outside world. The bed is, however, a space that offers a very particular type of energy for work!

VC: In the office the team was wondering if the images you make are from memories of real experiences.

SA: They’re real experiences, but they’re not necessarily personal ones. Maybe it’s a visual thing, something I saw in the street or in a movie. In that case, I did somehow participate in the thing – but in what way? It depends! I am speaking about myself here, but I don’t want it to be seen as a self-portrait. I’m more interested in making a self-portrait of a community.

VC: Would you say you’re a portraitist of a shared experience of imperialism?

SA: There is a large self-portrait in the exhibition where I imagine myself being knighted by Jean Genet – where they tap you on the shoulder with a sword. He tries to ennoble me, and I refuse. Genet really is one of those “primary sources” I described, a touchstone who I re-read regularly and with which I immerse and imagine myself into the types of scenarios in my images. Prisoner of Love, from the time at the end of his life spent on the Palestinian cause. It’s an obsession. I started reading Genet in Tangiers, at about 17, and I have never encountered it in the same way.

VC: The way we encounter mundane things, including the bed, evolves constantly too, I guess. I find your idea of finding “work energy” there so interesting, as someone who has historically had what I would call a complicated relationship with that space. There’s a lot of pressure to sleep, and to sleep well, and a lot of risk of, say, unconscious invasion.

SA: Exactly. Domestic space in general is something that must be constantly revisited. The history of western painting has described interior space as one destined for women, and men as existing outside it. The kitchen, the sofa, the bedroom – these are spaces that are extremely charged with stereotypes and complexities. That’s what interests me. That’s why sociology interests me. Pierre Bourdieu, for example, has dissected these spatial divisions in order to understand how we are made and why we act in the ways that we do. He also had an incredible vision on to how we consume information, which compels me immensely, especially with respect to social media, where there’s so much stuff that you either have to be “for” or “against.”

VC: Bourdieu pioneered the study of how people consume and assign value to art, specifically in French society. You mentioned that you intentionally stay at a particular price point with your drawings. I am curious if that connects to how you see or wish to see the consumption of your work by audiences. You work with galleries, where your works are bought and sold. Is drawing a way of pushing against this exchange of commercial and social capital – despite operating, as we’ve discussed, in the system’s own language?

SA: Choosing drawing as a primary practice is something that’s testing this capitalist market, especially given that the price of a drawing will always be a tiny fraction of the price of a painting. From that standpoint, there is a lot of choice in not going from drawing to painting and willfully staying within those limitations.

VC: Not everyone has studied at Beaux Arts or made a monumental sculpture, but everyone has made a drawing. How do you relate to the value or idea of artistic expertise?

SA: I try as much as possible to not think about it, to forget about it completely. But in schools where the training focuses on sculpture or video installation, no one is concerned with what is made by hand. I took that de-valorization as a kind of force – as a means of looking at how our defaults can serve to improve us. Of course, after at least a decade in France of institutions rejecting everything that is pictorial or figurative, now it’s coming back.

VC: At the Paris + art fair in the fall, it was all figurative painting.

SA: Totally.

VC: Ultimately, you teach to the market. And there is always people’s lingering desire to simply hang something on a wall. Is that what you want people to do with your drawings?

SA: There’s a whole trajectory — I start by making drawings, which form a kind of timeline of the exhibition, recording my experience of life from the moment Andre tells me we’re going to have a show on a given date. But whether it’s at a gallery or an institution, my involvement stops the moment I hang something up. There is no directive for how a person should receive it, or for how the institution should present it. I do get emotional when a museum buys a work, because I know it will come out again. I know the work will live. I was really moved when MAACAL, a contemporary art museum in Marrakech, bought a drawing. When I see an email telling me my drawing is in a group show and know that young Moroccans are going to see it and ask themselves questions about their communities, that fills me with joy.

VC: I was thinking of how someone in Europe might encounter a depiction of male intimacy by an artist of Muslim heritage as being purely scandalous, and not seeing any other cultural nuances behind it. Traditionally, public expression of physical affection between men — friends holding hands in the street being the classic example — is more accepted outside the global north, where it remains taboo.

SA: I did a project in Turkey around wrestlers who cover themselves in olive oil. The only way to beat one’s adversary is to put your hand in his pants and grab him and flip him. It’s an expression of extreme virility, to touch each other without thinking about it at all. Men holding hands is disappearing in Morocco, you know. And it’s the result of colonialism, of course. Women still do it, but men don’t anymore, not even in small villages. The occidental gaze has been internalized into the value system. They’ve adopted a western relationship to virility.

VC: Which is conservative, despite the west’s liberal self-perception. It’s imprudent and impossible to generalize, of course, but the way we narrate “freedom” to this day still seems like strategic marketing via the creation of a myth of its opposite.

SA: That applies to everything, not just the gay question — which brings us back to the ideas that got me working on this in the first place: the history of orientalism, the idea of the division of the planet into two parts, one good and one less good. Back to Edward Said.

VC: Would you ever find the post-colonial filter limiting, in terms of how your work is received?

SA: It’s just a positioning. It’s not limiting. It unites every artist who has ever been marginalized in history. It connects my work to the work I read by radical feminists. I’ve never stopped discovering things or finding ways to see things differently. That search is endless. But it’s just that at a certain point, you have to choose your direction.

Credits

- Interview: Victoria Camblin

Related Content

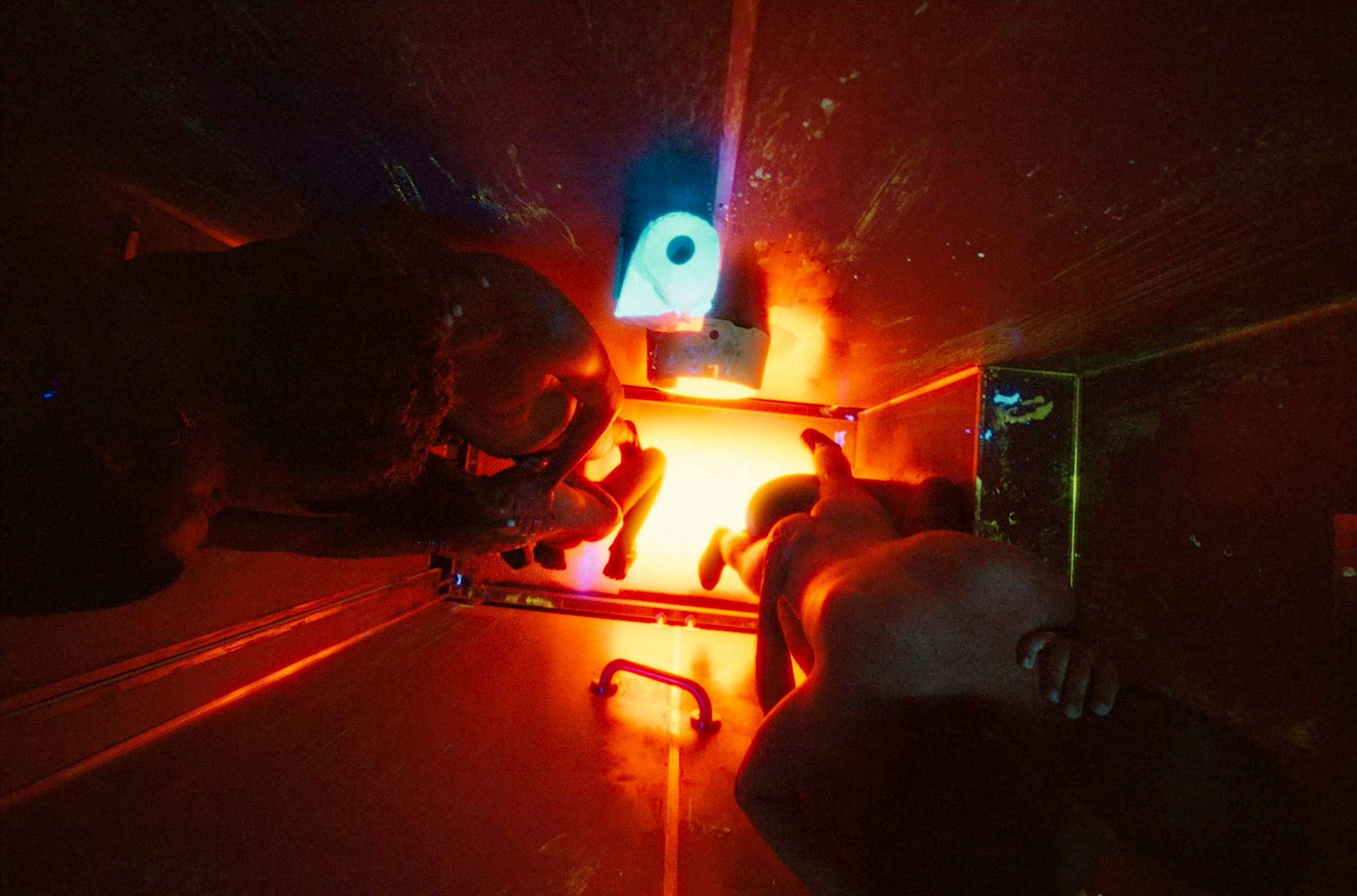

Cruise Centennial: MATT LAMBERT x LUDOVIC DE SAINT SERNIN for Pornhub

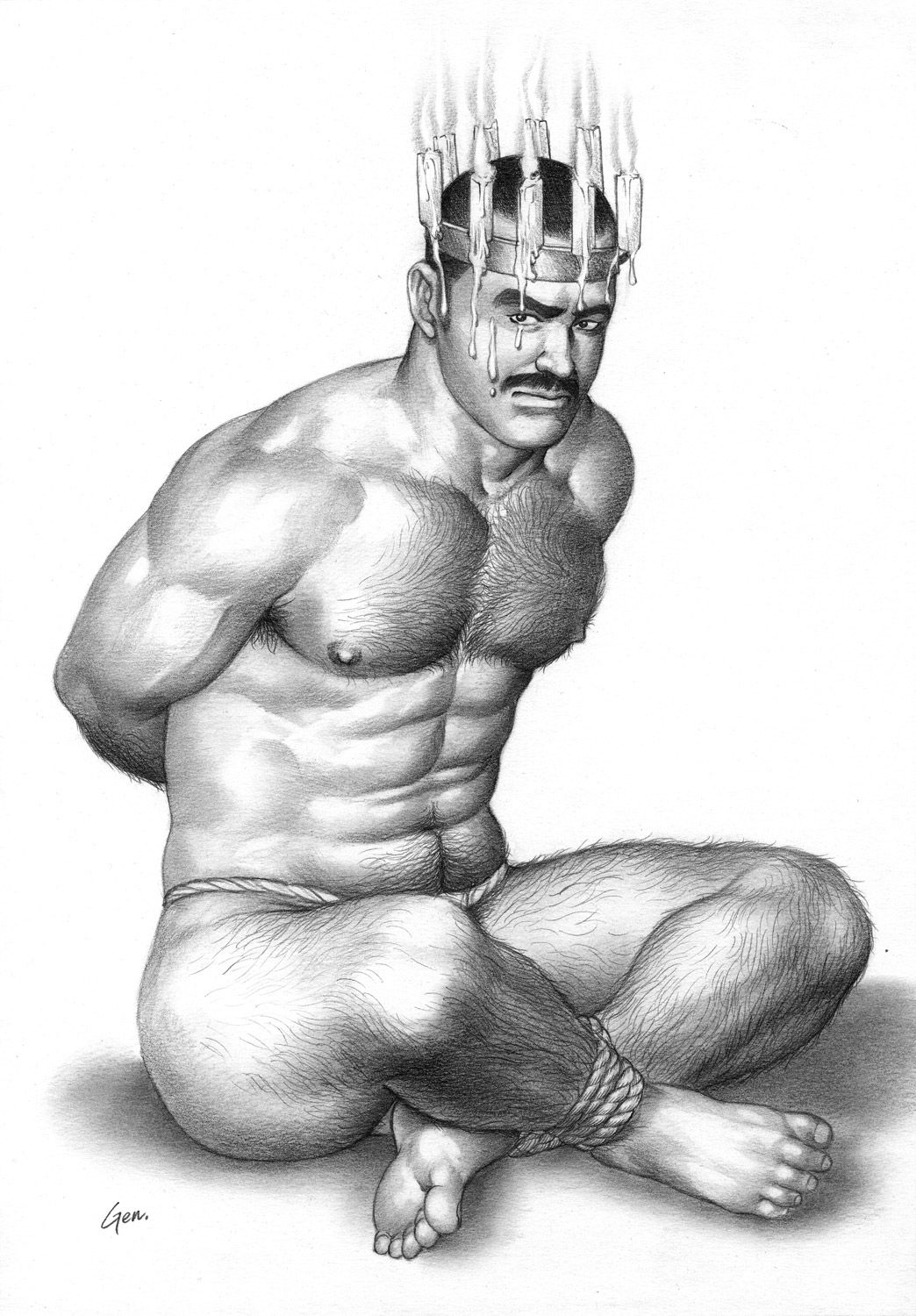

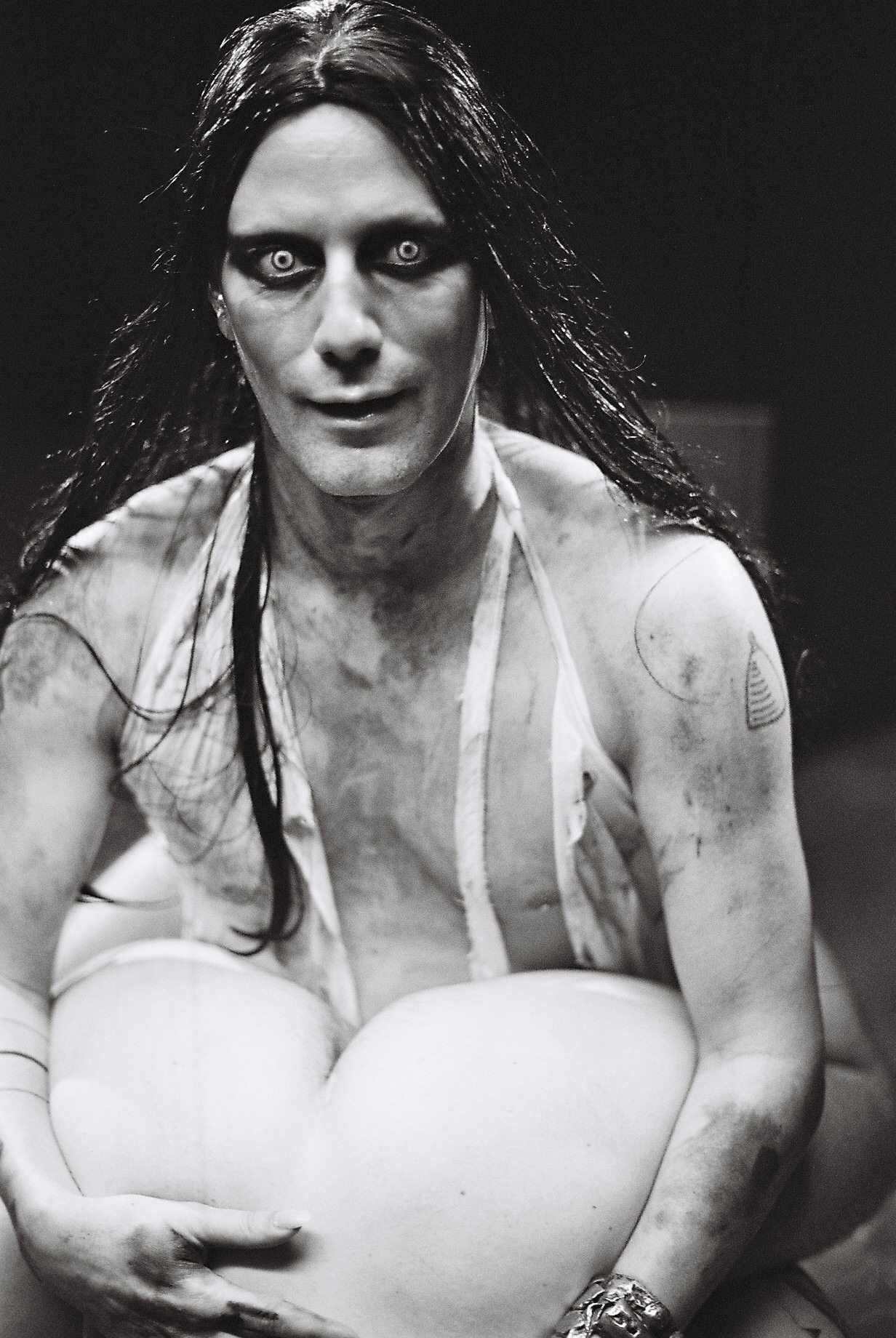

Japan’s Master of Gay BDSM Manga GENGOROH TAGAME Opens Up to 032c

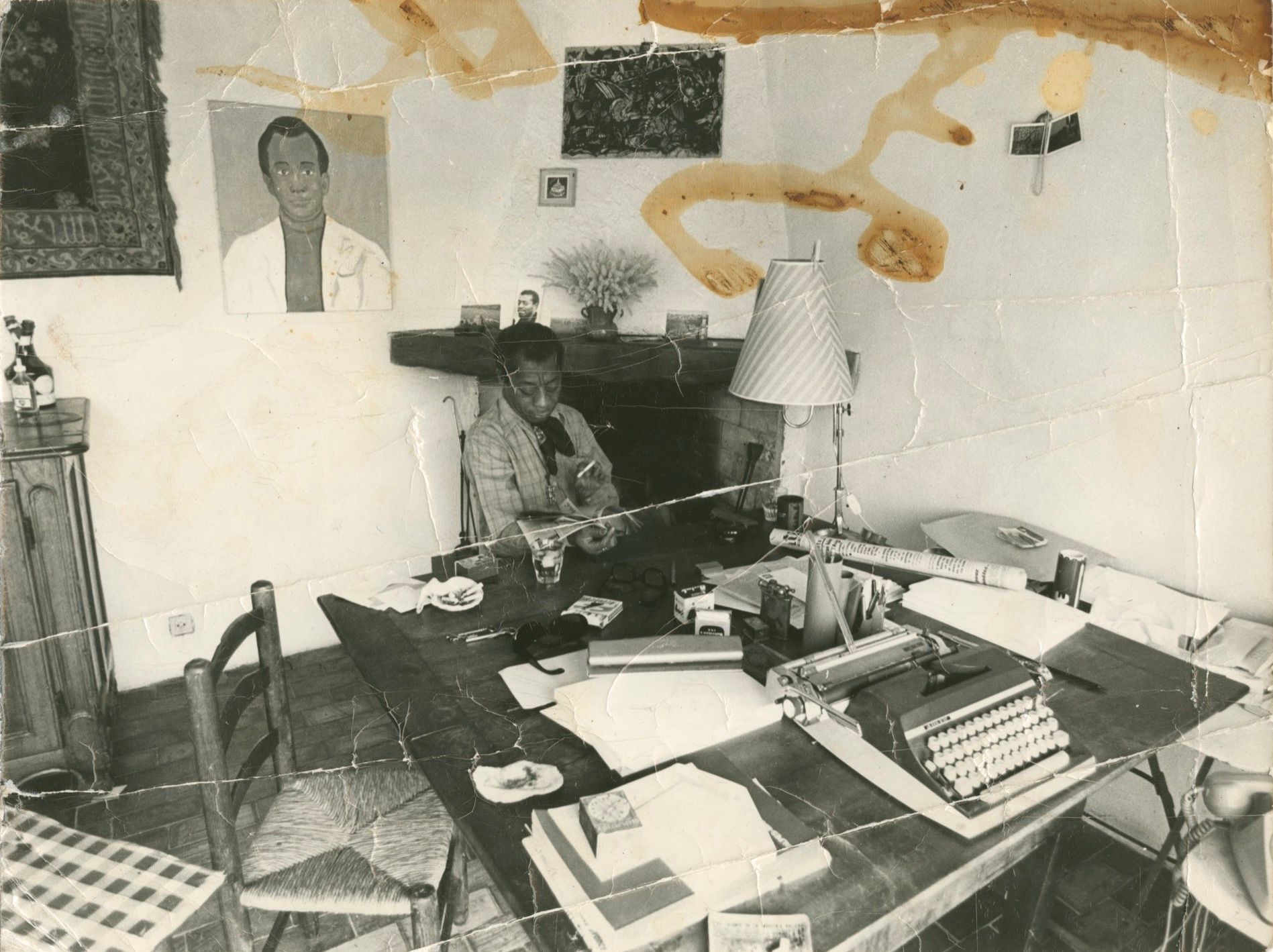

House as Archive: James Baldwin’s Provençal Home

ALVIN BALTROP and the Unofficial History of Cruising on Manhattan’s West Side Piers

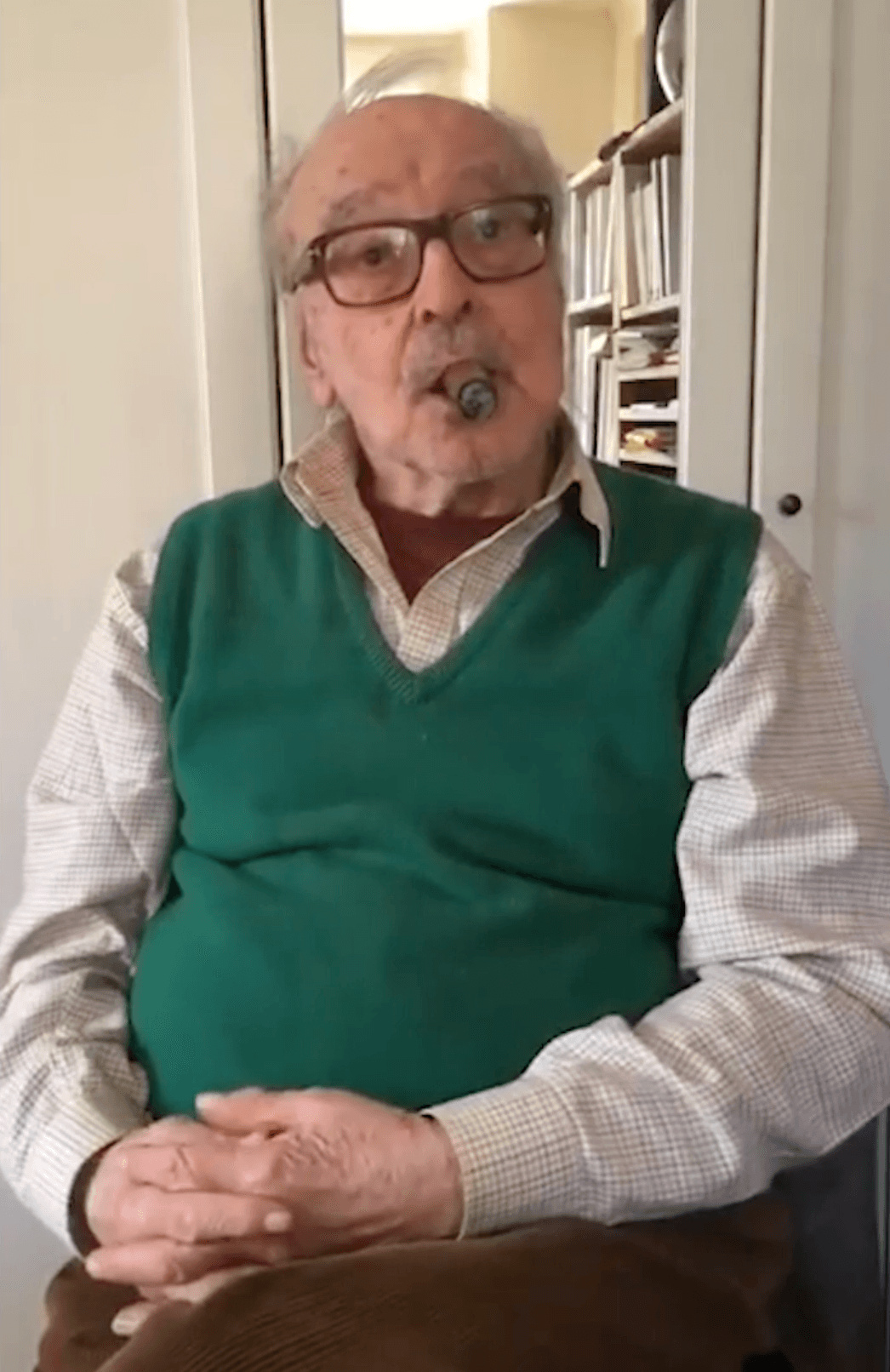

DEAR JEAN-LUC GODARD

ON MESSAGE: MATT LAMBERT and ERIKA LUST

Extremely Behind the Scenes: MATT LAMBERT’s “BUTT MUSCLE” Zine for Rick Owens

Brenda’s Business with RICK OWENS