Exclusionary Design: You Can’t Sit Down in Modern Cities

|Felicia Granath

In his book, Exclusionary Design (2017), writer and scholar Fredrik Edin addresses developments in civic architecture that reflect a “final” break from the West’s industrial and social democratic past. In the 21st century, Edin argues, we are given and denied access according to our ability to consume. Wealth dictates how a city must function and look. Corporations and their interests are the foundation of the built environment, and problems that might hurt those entities are confronted by design practices intended to be exclusionary: by the use of barriers around heating vents, by dull spikes on steps, and by obstructions placed under bridges and other covered areas – all interventions that prevent the use of public spaces for shelter or rest.

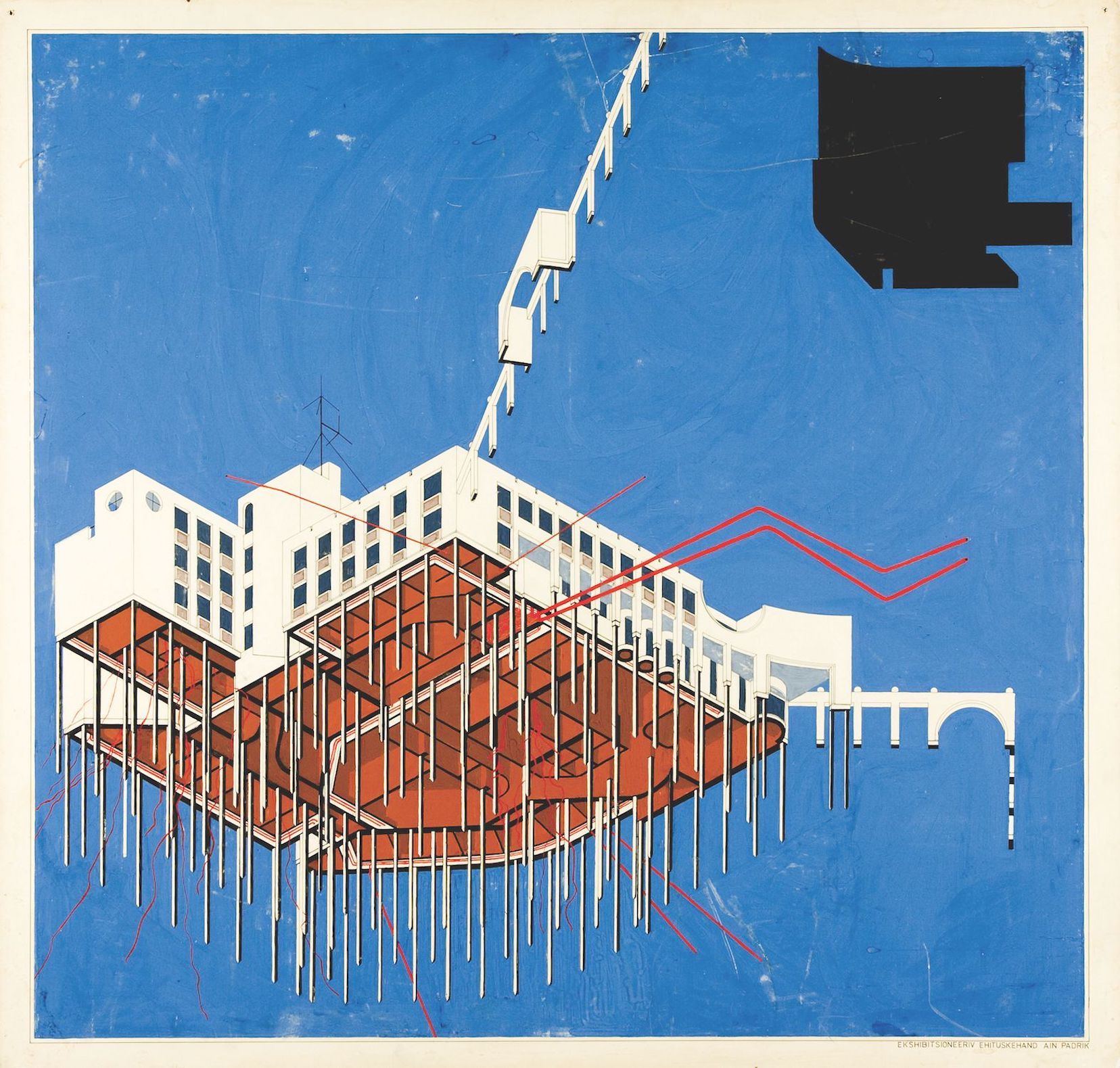

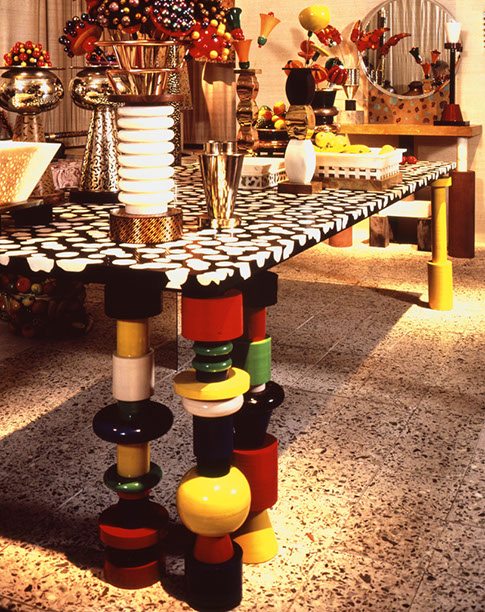

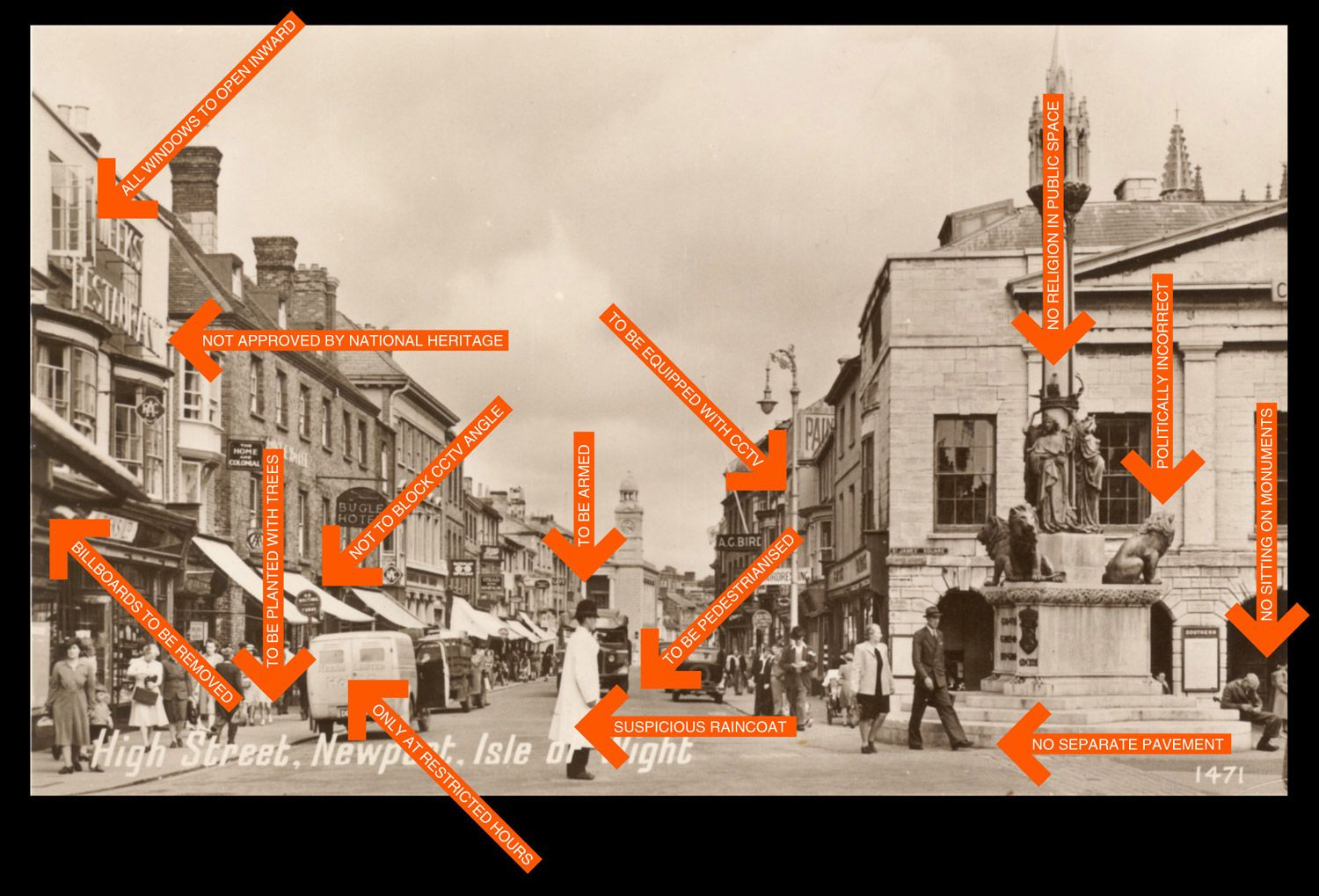

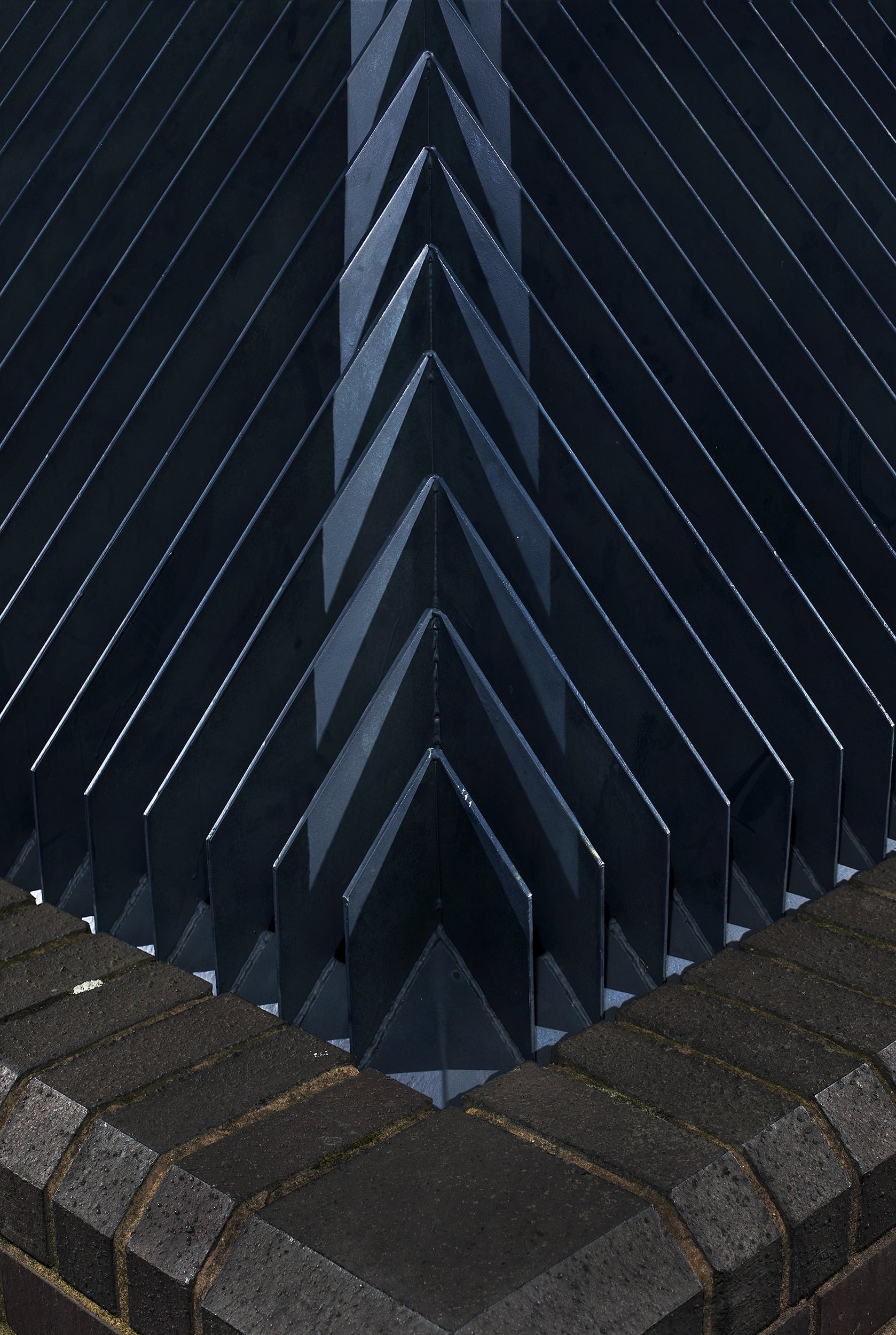

Edin illustrates what the city looks like for its “flawed consumer,” the deracinated citizen who is granted neither space nor freedom of access. The same transformation of the urban sphere preoccupies German photographer Julius-Christian Schreiner, whose ongoing project, “Silent Acts,” accompanies the conversation here and will be the subject of a forthcoming exhibition at the Stadtgalerie Innsbruck opening on October 3, 2018.

Felicia Granath: What brought you to write the book?

Fredrik Edin: I have always been interested in cities. What they look like and why, and their different power relations. My interest in exclusionary design began when the City Tunnel train stations opened in Malmö, Sweden, in 2010. On the platforms in the new stations are benches which are difficult to both sit and lie on. Anyone attempting to sit comfortably will slip right off them, and they were clearly built this way. I thought of it as a pretty interesting phenomena, since benches like these are common in stations. I searched online for information but could find almost nothing. There were criminologists discussing the subject, some sociologists, some architects. Over time, I became more and more interested in what this said about society, and saw connections to the privatization of our cities. It reflects a society where consumption has become increasingly important.

Let us clarify what exclusionary design means. You write and talk about the ways exclusionary design is practiced, and speak of the absence of objects and regulations as exclusionary too – public spaces without access to toilets, for example. What role does exclusionary design play in the advancement toward a more consumption-oriented society?

Those affected by this type of exclusion – homeless people, the poor, substance abusers, people begging for money and so on – are often excluded because they are not good enough consumers. I would say it is a way of dividing people. There are those who are viewed as consumers, and those who are thought of as bad consumers – and it’s far easier to eliminate the latter. The sociologist Zygmunt Bauman argued a completely new lower class was being created in society which he referred to as “flawed consumers.” Exclusionary design is a part of this process. The housing situation another.

I would define exclusionary design as referring to places and objects that have been created to keep flawed consumers and their activities out of sight. There are multiple reasons why this might exist: a familiar exclusionary design is one that prevents people from skateboarding. You might think the most common design is the leaning benches on train platforms, but I’d say it is removing objects completely. For example, where addicts tend to gather, the most common way to deal with these flawed consumers is to erase benches, public toilets, and bushes altogether.

Where does exclusionary design most often occur?

What they all have in common is that they appear in commercial spaces. There are some exceptions, such as putting up fences under stairs where one could seek shelter from snow and rain. I have even seen cages erected around hot air vents where people would seek warmth during cold winters. These are built where nothing of value really exists, which makes it seem more like pure evil.

Do we adjust ourselves to exclusionary design and internalize its standards?

I think we do – at least subconsciously. It’s important to remember that one of the fundamental intentions of exclusionary design is to camouflage social problems: nothing is solved, but poverty is temporarily moved out of sight. It creates a society in which poor people are degraded and chased from public spaces, which I think could have major consequences in the long run. If you look at certain cities – like Stockholm – people are incredibly segregated, mostly due to the housing market. I think it’s becoming more and more common that you do not see poverty. And the poor that are visible exist on probation.

I think we are affected even in cases where the design decisions are less obvious. Something I’ve noticed recently is the replacement of regular benches on train station platforms with bars you only can lean on. This is something taking place in both London and New York City. I think this decision makes it very clear that the station is not a place where one should hang out. Instead one should jump – as quickly as possible – on the first train headed in the right direction. This creates a behavior in us where you come to associate stations as a space you should quickly move through, at least unless it is a larger station or a central station where there might be stores. Then one can get some shopping done before leaving.

That was something that caught my attention while I read your book – how exclusionary design defines one’s attitude and function as, for example, commuters or consumers.

Malls and stations are constructed around the idea of us as commuters, or consumers, and no longer as citizens. The entire cityscape has been rebuilt according to the functions we require as people in a consumerist society. I believe that the old image of citizenship is beginning to vanish. We can no longer be considered only citizens. At the market we are consumers, and at the station we are commuters. The former meeting areas where citizens would interact and have a conversation, that aspect is vanishing from the cityscape.

Perhaps it has moved online?

One can look at social media as some sort of replacement to physically manifested meeting areas, but in my experience it is rare to genuinely meet random people online. The people you do converse with are your Facebook friends or Twitter followers, and either you chose them or they chose you. It’s unusual for me to communicate with a stranger on Facebook. I think that random meetings as explained earlier are being redefined.

What object or aspect of the city do you fear is next to become inaccessible?

In London there is some discussion about “pseudo-public spaces”. These occur when a municipal government decides they cannot afford to care for a place like a park and street. So they lease these spaces to corporations in exchange for property maintenance. It hasn’t really been implemented in Sweden yet, but where this happens in Great Britain companies are granted the role of authority by the municipal government. They are even able to establish their own rules of conduct for the spaces, referred to as “Business Improvement Districts”. In Sweden the closest practice to this is municipalities that put extra resources into corporations in a district. But in Britain the attitude within municipal government is much more like: “Alright. You get to manage this street and you are basically free to administrate it however you like.” As a result of this a municipality have less expenses and can lower their taxes, meanwhile jeopardizing the idea that public spaces belong to everyone.

In your opinion, what efforts are needed to steer the development of exclusionary design in another direction?

There are no easy solutions to the problems exclusionary design attempts to hide: social immobility, substance abuse, homelessness and the shortage of housing, to name a few. On a grand scale it’s about trying to create a more equal society: to reduce barriers, build homes, create a more humane and accessible healthcare system. For the individual it narrows down to organizing yourself locally and trying to affect your immediate environment. Collaborate with neighbors and friends, occupy spaces, install neutral benches in public spaces. We must address politicians, landowners, municipalities and corporations on this matter.

Credits

- Text: Felicia Granath

- Photography: Julius-Christian Schreiner