Uchronia Without Bounds: London Hardcore

“Even the most private accounts of catastrophe,” I think later, leaning in the corner alone to take a rest and down my umpteenth beer, “experience a transformation here, via noise and euphoria, into a generic fucked up-ness excluded on all sides from the fucked up-ness that was here the object of jubilation.” Everyone here acts like everything is different from what it is. That is the enigmatic appeal to the dignity of nocturnal ferment and endless celebration. It's irreducibly local and at the same time, yeah, that’s right, utopian dimension.”

Excerpt from Rave by Rainald Goetz (1998), translated into English in 2020.

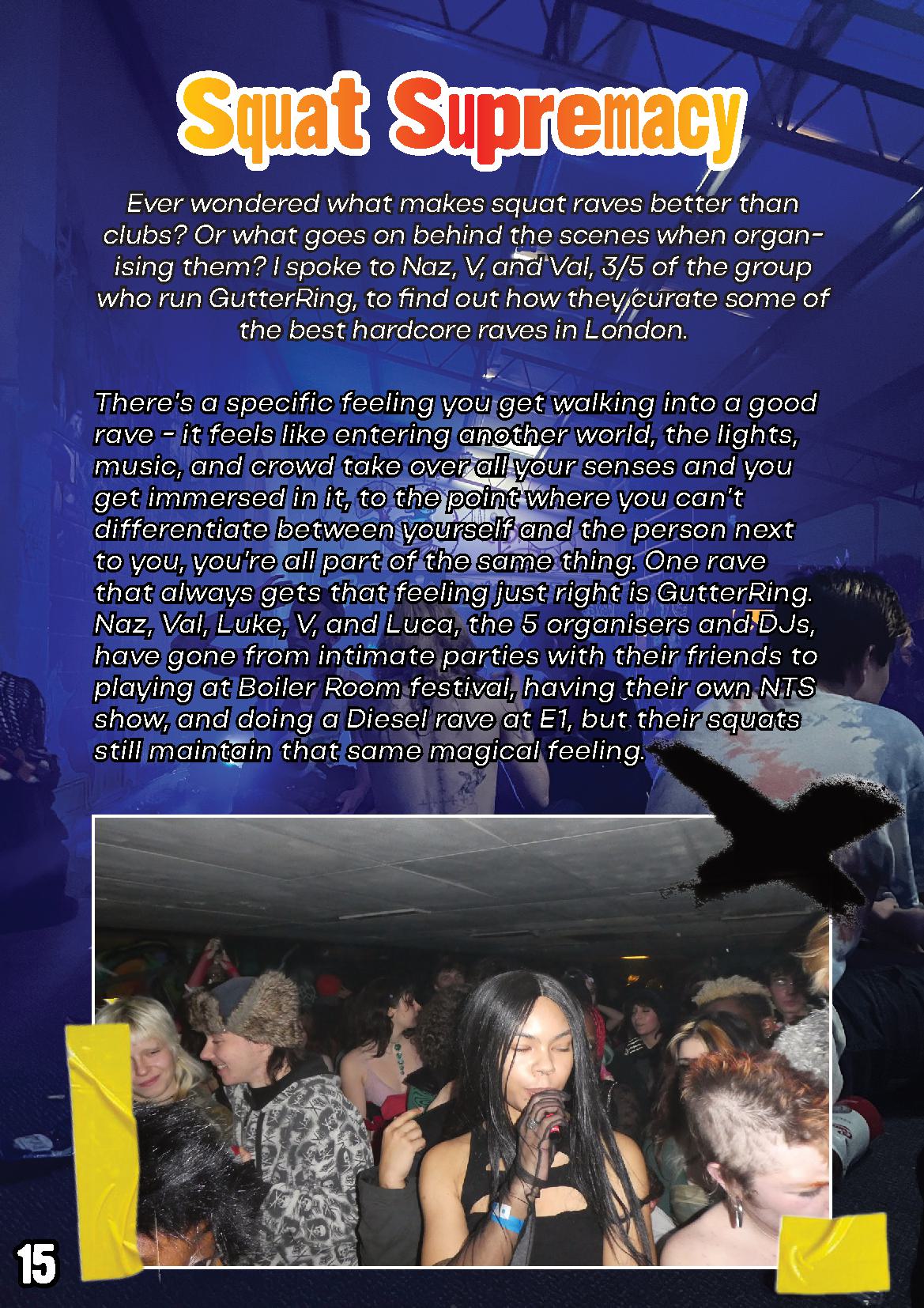

The London Hardcore youth exist in corners of London that no one has heard about, no one has visited. Whether it be a warehouse in the far reaches of South London or a basement on Dalston Kingsland, it is in these cavities that they create their sanctities through sound, style, and community. In its current configuration, the Hardcore scene took off in London's queer, marginalized, creative communities following the Gutterring raves' success post-lockdown. Now, many other events of the same nature have popped up and thrived, creating euphoric euchronias and other-worlds for those who don't fit into hegemonic society.

London Hardcore thrives on an amalgamation of influences, extending what it means to be hyper-individual into a new realm. The Hardcore sound is punctuated by earsplitting styles from the 1990s, such as gabber and donk, combined with an extensive range of sped-up samples, an uncompromisingly complex sound, and high BPM. Much like the clothing style, the music that comprises samples, pre-programmed drumbeats, and already sung voices is a recycled mode in perpetual movement. London Hardcore thrives in this blend, belonging to everything and nothing at once; it is truly a world of its own.

Lucy Broome speaks to rave collectives Genesys and GR1N, and to Héloïse Shadbolt, founder of Rapture magazine, to explore how rave’s legacy of world-building is finding expression in London’s current scene.

GENESYS

The Central Saint Martins duo Paritos Tamang and Rain Mueller created the Genesys club nights in June 2022. Describing their collaborative work as a “symbiosis,” Tamang and Mueller situate themselves on the techno side of Hardcore but their club nights have greater spiritual goals.

LUCY BROOME: What exactly is Genesys the origin of?

RAIN MUELLER: The way we spell Genesys refers to when multiple organisms work together, like a system.

PARITOS TAMANG: And what’s being originated is a new culture.

LB: Rain, I’ve heard that you are the tenth avatar of Vishnu, who was sent to this realm to return man to the dynamism of nature and free humans from the decadence of this age. Is that right?

RM: That’s true to an extent, and Genesys is largely a way for us to do that.

PT: It cultivates this relationship between people, technology, music, and art, so that they can come together and create this new culture.

RM: There are many things that are crushing the human spirit and in the Hindu prophecy, this is called the Kali Yuga —the age of decadence. The way to return to nature and enter the Satya Yuga, the first stage of the Hindu Yuga cycle, is through euphoria and ecstasy. We can create this by coming together and sharing these profound experiences and entering a trance state. Genesys is a hive mind. We’re trying to bring all these people together in a very literal sense. This is the place where young people can come and create the future. I’m sure that many amazing projects have been born in the smoking area.

PT: And new lifelong friends. For a lot of people, if it’s their first time experiencing a rave in London, we can change their expectations of what a party could be.

RM: By the way, I’m not really the tenth avatar of Vishnu, it’s a metaphor.

LB: Then who is Vishnu?

RM: Vishnu is part of the Hindu pantheon, the Trimurti which consists of three gods; the creator, Brahma, the destroyer, Shiva, and Vishnu, the upholder, the architect. Essentially, at the end of each age, Vishnu is incarnated on Earth through an avatar. So, maybe it is me, but it could be any of us, who brings the end to one age and ushers mankind into a new one.

PT: It’s a kind of philosophy that we try to convey through parties.

LB: Pari, would you also situate yourself in this mode of Hindu ideology?

PT: In so much as we said about Genesys being a hive mind and a collective consciousness. We really want it to be this universal, shared experience and bring light to this way of thinking about rave culture.

I grew up in Nepal, which is a largely Hindu and Buddhist population, but it’s Christian as well—there’s not one dominant religion, it’s a mix of cultures. Similarly, London is a place of cultural mixing.

RM: Spirituality definitely influences our process. The thing about Genesys is that our narrative isn’t necessarily fictionalized. We’ve worded it in a very creative way but everything we talk about is pre-existing ideas, such as the gods of Genesys. We’re also inspired by a concept called egregore. It’s an entity or a spirit that’s born from the minds of the collective. For example, there’s the egregore of football. When all the fans come together, the thing that’s above them is the egregore of football. It’s a spirit that’s born from the collective, and that exists in Genesys. Every cultural movement has that, but maybe they don’t acknowledge it.

LB: A lot of your work is situated in the digital, which people often associate with being disconnected from cultivating “real” connections with people.

PT: There can be a disconnect with technology, but we try and use it as a tool to help connect more people. RM: In our early raves, we were streaming in VR in collaboration with a company called Club Mix.

PT: They essentially let us use their venue whilst they streamed and recorded it. It was an example of a very symbiotic relationship.

RM: We put a lot of emphasis on symbiosis. Whoever we’re working with, we want it to be mutually beneficial. With the first venue, they streamed it with a 360-degree camera and broadcasted it into the metaverse. People from all over the world could join and rave. We hope to do that for our next rave as well.

PT: Yeah, we’d like to delve further into the digital realm.

PT: We’re more real-life than online in that sense.

Genesys very much has a vibe, and one way to communicate a vibe is through music. And I’d say the next way is through clothing. By the end of our existence, before the organism of Genesys collapses and dies, we want to cover everything that a human could involve themselves in. Genesys as a rave is just the starting point.

RAPTURE

Héloïse Shadbolt visits the throngs of the club nights, often frequenting more than three raves a week—all for the sake of good journalism. She started her zine Rapture taking pictures of her friends and fellow rave goers, whose eccentric dress she felt compelled to document. Now Rapture is the scenes lead (and only) publication.

LB: What was the inspiration for Rapture?

HÉLOÏSE SHADBOLT: I’ve always been a massive fan of Fruits. I love how Shoichi Aoki takes photos of people. When I started going to raves, the interesting and individual ways people dressed reminded me of Fruits, and I wanted to document them in a similar way. Rapture began as a uni project, and I started my research by poring through all the volumes of Sleazenation in the library. I was looking at these issues from the 90s and early 2000s. Compared to other mainstream magazines that talked about culture, fashion, and music, it was a lot funnier and didn’t take itself too seriously—it pushed the boundaries of what was acceptable to talk about, like drug culture. I could easily analyze the Hardcore scene and make grand statements, but I wanted to make a zine that captured the energy of the scene rather than just intellectualizing it. I wanted Rapture to be the scene but in the format of a zine. I thought the best way to do that was to take influence from the tongue-in-cheek style of Sleazenation.

LB: How would you describe the Hardcore sound?

HS: I’m not educated in the music, I don’t know about the technical aspects, but I can talk about how it makes me feel. When I first started going to raves, all the music felt very euphoric. The hardness of the sound, the intensity of it, means you can’t get distracted or think about anything else, you’re so in the moment. You dance very intensely to it and everyone just fully lets themselves loose. When I got there, the music was so overpowering and the people were dancing so wildly that I felt like I could dance like that too. It gave me this feeling of freedom.

LB: How would you describe the dress of the Hardcore scene?

HS: In my opinion, the style of dress reflects the music. Because there are so many different sub-genres within the broad term “hardcore,” the music you hear at raves is an amalgamation of so many different sounds, and so the same goes for the style, people take influence from everywhere. For many, raves are a space where they can dress up, especially if they don’t feel comfortable dressing that way day-to-day. You’ll see people in outfits that look almost like costumes, like they’re dressing for another world. But then also I’ve got a friend who literally wears his gym shorts and a plain t-shirt. He goes and has a great time, and doesn’t feel any pressure to look a certain way. You can’t define the Hardcore style because everyone wears something different. There is no trend to follow. It forced me to think about what I wanted to wear for myself. I found my own individual style by going to raves.

LB: Why do we rave?

HS: It gives us an alternative. Throughout history, people have found a way to get in touch with the side of themselves that isn’t accepted in mainstream society. In psychology, there’s Freud’s theory of the ego, which describes the superego, ego, and id. The id is the freest, most hedonistic part of yourself, and your ego controls that. At raves, you can really immerse yourself in satisfying your id. Throughout history, in places with strict ideas of societal norms, people, especially marginalized people, have found somewhere to go where they can be themselves without judgment. You can go to clubs, but I feel even in clubs in the UK you have to dance a certain way and you have to act a certain way. When I started going to raves, I met people I connected with.

Everyone was so accepting and open, and I felt like I could be myself and dance freely. I would go back to work or uni and feel happier, refreshed even, because raves felt like a release.

LB: Do you think raves should be documented?

HS: I don’t think people should be going for the sole reason of making content. You want people to be in the moment. But I do think documenting it is important because we wouldn’t know about half of subcultures in the past if they weren’t documented. Yet, there’s documenting things in the right way, and then misrepresenting them. That’s why I’m really careful with my zine, trying to present the scene in its truest way—but even I struggle with finding that middle ground. I try to include as many perspectives as possible with the people who contribute to the zine, so it doesn’t just come from one viewpoint.

GR1N

If you enter a nefarious space and see a group of 20-year-old somethings dressed in masks and performing ritualistic activities to the sound of earsplitting gabber, you’ve probably wandered into a GR1N party. Acting like a cult and incorporating installations and performance art into their club nights, GR1N asks ravers to commit an act of “positive surrender.”

LB: Where did the name GR1N come from?

GEORGE MURPHY: We had to do this design project at university. GR1N was initially this character who would infiltrate weird NFT Discord forums.

LUKE CAHALIN: The project was about showing how fragile new markets were. We’d go on forums under this fake alias “GR1N” and convince people we were experts in the NFT marketplace. It got to the point where we received an offer from a Swedish football company to consult them on an NFT project. We really know nothing about NFTs, but we were showing how easy it is to become someone who is trusted. Although the alias doesn’t directly relate to what we do now, it was easy because we already had the Gmail account.

LB: How would you describe the GR1N sound?

PM: For me, personally, my favorite stuff is when it’s the most fucked up noisy sounding thing you’ve ever heard but it’s also incredibly catchy.

GM: A lot of hardstyle remixes do that. The beat and everything will be so heavy—but then it’s still got Lana Del Rey in it. Then you think about stuff like Brutalismus 3000, which exists in the same sphere, but they’re also situated in a very different genre. I’d say the music of the scene in general can sometimes be heavily influenced by Yung Lean, Drain Gang, and things like that.

LB: The themes of your installations are pretty unconventional, where do you take inspiration from? The first one I saw was “Panopticon,” which is an interesting name in a rave context.

PM: We normally have a well-thought-out narrative, where we’ll sit together and write a sort of lore as to why there would be a gathering of people in a space listening to music. We want to tell a story. From there, we look into how we can make it more immersive and believable.

LC: We want to achieve immersion and the idea of surrendering to something with the raves. That’s where the themes come from. The panopticon idea is about having to surrender to a group authority. That encourages people to let loose. You’re surrendering to being told what to do.

The recent “Inner Circle” raves were taking that in a more spiritual way. We want to recreate this surrender in the same way that you might submit to a deity through communal engagement, like when you go to a church and sing in a choir. We then want to channel that into our fictitious environments.

GM: This is where costume comes in. On a day-to-day basis, when you’re repping brands and everything on your street clothes, you display your personality through those things. When you give that away, it’s like you’ve surrendered an element of yourself. It’s like you’ve surrendered your ego. It makes it a much more fun and playful environment.

LC: It’s why I wanted people to wear masks at the last rave. Obviously, it fits with the theme of an Eyes Wide Shut cult, but at the same time, it allows people to be less self-aware. They’re more likely to fully commit to having a good time and enter this flow state.

PM: Simultaneously, there is self-expression in what you choose to wear. It’s a mixture of the two.

LC: It enables self-expression but it also allows you to surrender the individual pressure that you might feel outside of it.

PM: In terms of the music, we like to involve it in the story. We’ve had a few artists who will curate their mixes as part of the narrative.

LK: For the last show, Swan Meat’s visa, unfortunately, got canceled so she couldn’t come in person. Instead of not involving her at all, we wove that into the narrative. We got her to record a video, which we then had somebody in costume hold up and play on a monitor. The video made it seem like she had been held captive by a cult. Then she redid a premix for us with sections of spoken word woven in. That continued the story of why she couldn’t be there but re-contextualized it in this fictional world we built.

As Peter said, when we are making installations for the space, we sit down and write a lore or narrative about why we’d be there. That situates it as a space that could also be a real space. The space evokes feelings we’ve had from real spaces we’ve drawn inspiration from. For this next show, we’re drawing inspiration from churches in the main room. We want to have some degree of tunnel vision through faux pillars. There’ll also be a piece of geometry on the back, which would be reminiscent of the east window of a church. Even if it doesn’t look like the real place, it evokes the same feeling through the borrowed design elements. The installations and the spatial design are a big part of it, for us at least.

GM: In any city in the world, you can see someone plug in a USB. Something that sets the London scene apart is how it is framed in this whole aspect of giving a narrative for why it is happening. It creates a fuller immersion. It’s an immersive landscape that can even travel around if you like—it doesn’t just exist in a nightclub. It can exist in an art gallery or a multiplicity of alternative environments. Once something becomes that immersive, it transcends the space it is in.

PM: Our generation’s view of the future is a bit pessimistic. We might not have a bright future. The raves can write this complete other-world you can pretend you’re in.

LC: We have to make fictional narratives because the real, current state of the world doesn’t facilitate a positive surrender. You have to create these “fake” spaces for people to do it.

Credits

- Text and Photography: LUCY BROOME

- Lighting: LUCA MARINO

Related Content

“I Don’t Want Anything”: An Interview with ECCO2K

Legion of DUMA: Nairobi’s hardcore duo premieres a new video

“The Bigger the Risk, the Bigger the Reward”: JUERGEN TELLER’s Reasons to Enjoy Your Life

RAVE: Before Streetwear There Was Clubwear

GOSHA RUBCHINSKIY: Inside his Vertically Integrated Youth Universe

ALESSANDRO SIMONETTI Captures Italy’s UNDERGROUND SPEED FANATICS

“Nepotism Is All I've Ever Wanted”: An Interview with BAKAR