Runway Music: Musicology for Clothes

|FEDERICO SARGENTONE

Finding the good among the chaotic mechanisms of the creative industry is a practice that needs to be campaigned for. To look for exceptional details within the commercialisms of the industry is a mission.

I have undertaken the laborious task of dissecting the gray zone of cultural production between high and low. I’ve embedded myself in the dangerous field of cultural criticism, where a commercial image bears as much significance as a theater play or a sheet of piano music. Fellow literati — contemporary and since passed — might very well roll their eyes, but we are on an avant-garde- and kitsch-energy boost here. Mix it with some ice-cold Raymond Williams and you get the point.

The archetypal product that I believe sets the blueprint of the much-discussed high-vs-low cultural production is what one could call “runway music.” Runway music is music produced, selected, purchased, cleared, used, commissioned, or, in some cases, stolen, for the purpose of augmenting the presentation of clothes. How? Through sound, duh. “Presenting clothes,” varies in form: it could be a runway, a fashion film, a TikTok video, an Instagram reel or story, a branded YouTube post, or any medium that could formally imply the presence of sound.

What intrigues me about this C-tier creative practice is its disposability. In this context, an mp3 file of about 20 minutes often transcends its physical format to become abstraction — sound branding. Yet we have winners and losers in the runway music game. Brands doing it right, and brands simply doing it. Although the pleasure of analyzing the products of this game resides in the unexpected moments of genius, escaping the predictable route of commerce.

Womenswear SS-23 collections unfolded through the usual fashion month schedule this autumn. To escape those routes, creative directors aimed high — not necessarily in terms of altitude, but in terms of erudition. As someone who has been commenting on and critiquing experimental music for years, I am shocked to see how the “classical orchestra” trend has permeated the fashion sound arena. What is even more intriguing is the functional psychology behind those music choices. As previously acknowledged, runway music is essentially sound branding, hence it is often a tool to position the brand in some specific area, and here, classical music is reciprocally treated as a brand too — a luxury brand.

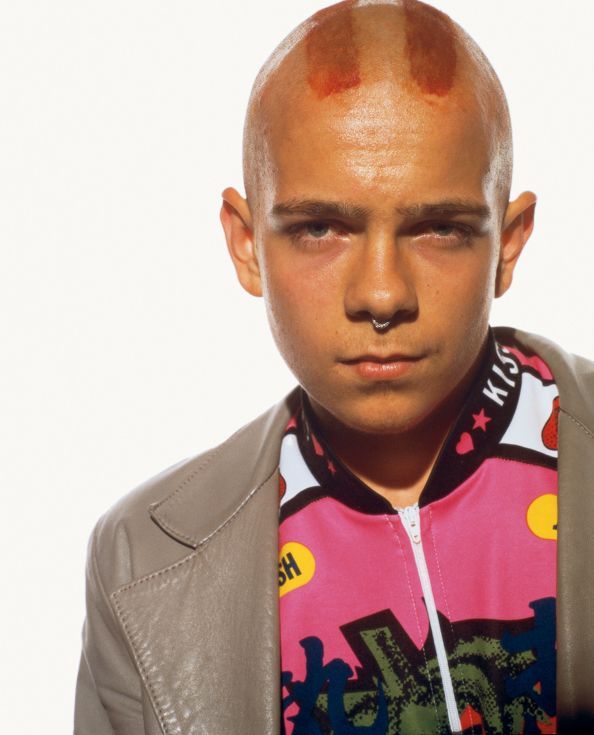

Burberry

For his Burberry farewell show, Riccardo Tisci devised a sonic quasi-dramaturgy, oscillating between stark silence and soprano-sounding vocal incursions. The opera piece was commissioned to the Welsh composer Paul Mealor and performed by American superstar soprano Nadine Sierra. It was accompanied by the London Contemporary Orchestra, whose musicians were dressed in black baseball caps bearing the Thomas Burberry TB monogram. As press and critics advanced the hypothesis of Victorian influences in the collection — lace, crochet, bustier — the orchestral take could make sense, formally. But conceptually, it delivered a blockbuster version of something that had not quite succeeded in sounding elevated enough. If it is true that opera singers were the celebrities of the Victorian age, I wonder what the actual celebrities of today thought about the soundtrack of the show. And, trust me, there were many. Obscurity! Illusion! Drama! Theater! The aria and the Air Max collide…

Act II. Scene I: Curtains rise. It is 1913 and Sergei Diaghilev's Ballets Russes company is premiering a new show at the Théâtre des Champs-Élysées in Paris. The belle époque is fading off, disappearing with the outbreak of World War I one year later in 1914. Civilization is, undoubtedly, at its peak. On May 29, 1913, at the Théâtre des Champs-Élysées, an unknown Igor Stravinsky debuts his orchestral work Le Sacre du Printemps (“The Rite of Spring,” 1913), a seminal work that will cause huge indignation among the Parisian theatergoers, members of the high society, and cultural establishment. That night, Diaghilev's Ballets Russes brought to life a piece of music avant-garde, and Stravinsky — for merit or shame — became a social sensation.

MM6 Maison Margiela

Flash forward to 2022, and the Milan Symphonic Orchestra is revisiting Stravinsky’s composition in a borderline mash-up with motifs from film soundtracks and one “sample” from Laurie Anderson’s 1981 experimental hit “O Superman.” Looks from MM6 Maison Margiela’s MM6 SS-23 collection flow around the audience while harsh, almost cacophonic sounds hammered the atmosphere with brutally modernist symphonic stabs. Sounds fill the auditorium through dissonant combinations of sounds that do not belong to traditional harmony and broken-up rhythmic sections give space to spooky oboes, clarinets, flutes, trumpets, and trombones arranged to disrupt metric and tonal symmetries. Like Martin Margiela himself revolutionized the canons of style, Stravinsky — who composed the piece in a microscopic room furnished with only a muted upright piano, a table, and two chairs — invented modernism as soon as his pen left the last mark on the score of Le Sacre du Printemps.

Marni SS-23

The “Rites of Spring” — Printemps/été 2023, specifically — keep moving on and another orchestra is yet to play on stage. Marni SS-23 in New York is giving counterpoint, a compositional mode, rather than a technique, which has influenced music since the Renaissance, resurfacing as the leading trend in the Impressionist works of Erik Satie and Claude Debussy. In the 1960s, the New York Downtown scene fused the non-representational ethos of Minimal art into music, creating new forms of experimental composition. Composers La Monte Young, Terry Riley, Steve Reich, and Philip Glass are credited as the initiators of the leading avant-garde in contemporary music, and counterpoint became their weapon of choice. For Marni to show in New York might seem odd, since the brand is strongly tied to its Milanese heritage, but what is not odd at all is its soundtrack. Written by Minimalism aficionado Dev Hynes and performed by the String Orchestra of Brooklyn, the score is highly site-specific to New York City, featuring spiraling string voices that overlap and desynchronize in a stream of consciousness-like flux of disharmonies. If in Reich’s seminal New York Counterpoint movements are repeated in patterns and are structurally arranged in pulsing rhythm, in Hynes’s piece we see a more dramatic approach to symphony, which furthers the starkness of the Minimalist school to a much more layered, empathic, or emotional catharsis. Truth be told, both works evoke the City’s chaotic rhythm in great detail, with Hynes exploring the more Baroque-leaning polyphonic sound vortexes.

Comme des Garçons SS-23

There is nothing more effective than a vortex of strings. Everyone loves a good string melody, because it is direct, it is heartbreaking, it is classical, it is humane. Strings are to emotions what elegies are to tears: perfect vehicles. In his 1936 classic, Samuel Barber’s Adagio for Strings, violins build up a melancholic atmosphere full of anticipation, with pathos climaxing in sad, chant-like melodies. Barber’s blockbuster, which I suspect to be a sample in the legendary Aphex Twin (AFX) “P-String” track, follows the symmetric structure of the “adagio,” where a melody that first ascends and then descends within a central movement. A straightforward structure that easily lends itself to melancholic timbres, also due to its slow-paced tempo.

An adagio introduces Comme des Garçons SS-23 show in Paris. An angelic string piece by Greek composer Eleni Karaindrou, whose music is used throughout the show. Karaindrou’s music is a gem, produced with extreme sonic sensibility and emotional attunement, incorporating motifs from popular music. She has composed mainly for films and uses folk elements derived from the Greek-Byzantine tradition to paint vivid pictures.

As the orchestral trend signals a shift away from the traditional 4-to-4 rhythm heavily employed in runway soundtracking, it also implies the commitment of major luxury brands to shy away from the hedonistic depiction of fancy clothes worn by models on a runway. Pivoting to what is “classical” has emerged as an aesthetic trend for many brands that either reconnect with their heritage or propose a reconfigured version of “timelessness.” Of course, this classicization in design and ethos traversed into the sonic field as a trickle-down effect. When we hear about some brand’s “icons,” “timeless pieces,” or “heritage,” we can’t help but ask: “what is a classic today?” I am not sure whether a symphonic orchestra playing a delusional Dadaist mash-up is an innovative gesture or a sonic suicide. A classic, by definition, is a cultural object that not only doesn’t lose meaning over time, but also continues to acquire significance and keeps being purposeful, or consumable, as time passes. A classic is cemented in time, although dynamic in its openness. As we usher into a new phase of orchestral sound branding, I am left with serious questions about whether, by reciprocity, the runway had become the theater stage, and whether the front row is the audience or the spectacle.

Credits

- Text: FEDERICO SARGENTONE

Related Content

Why WOLFGANG TILLMANS Has Re-Coded Recorded Music into an In Situ Experience

Lust & Sound: Man About Town MARK REEDER’s Forgotten 80s Berlin

RAVE: Before Streetwear There Was Clubwear

Transmissions: NFTinis, Skirt Sets, and Cognitive Dissonance

The Road to Burberry: An Interview with RICCARDO TISCI

BERLIN by RICCARDO TISCI

TO LOVE ALONE

The Future of Couture: Neo-digital natives, blockchain luxury, and algorithmic customization