Iceberg's Visual Soundscapes

|CLAIRE KORON ELAT

In 2016, designer James Long received GQ’s Breakthrough Designer of the Year award and was named creative director of Iceberg, the Milan-based luxury brand that was one of the earliest proponents of streetwear. Founded by Giuliana Marchiniand Jean-Charles de Castelbajac in 1974, Iceberg became famous for its irreverent knitwear featuring cartoon characters such as Bugs Bunny, Tom and Jerry, and Mickey Mouse. Now that Long is at the helm, he is adding his own distinct twist to the brand’s legacy. Known for mixing leather with satin and jerseys, Long is someone who loves contradictions.

HENRY LEVINSON: When did you first start leaning into contradictions?

JAMES LONG: For me personally, it’s natural, because I live between two countries, Italy and the UK. It’s just what happens. And I love contrast in furniture. I love period pieces with something very modern. I also love it, when I’m dressing myself, ... to contrast something very streetwear with something high-end or the other way around. In my design work, I’ve always loved leather textures against knitwear, which are really contrasting, and that’s in the brand’s DNA. Even in the collections, there’s tailoring and then there’s something very sporty. I need that sharpness to balance the softness and to create those opposites. There’s something brilliant about accepting everything and not closing yourself to one thing. You need to have both to know the middle.

HL: At face value, cartoons, which Iceberg is famous for integrating into its designs, might seem to be a contradiction to haute couture. How have you integrated these iconic aspects of the brand legacy into your work as a creative director?

JL: Fashion is quite cartoony at times. People change their bodies and whole character with clothes. I often talk to people who study fashion about the power of clothes and their transformative value. If certain clothes make you feel good and make you feel like you can transform, then that’s an amazing thing to have, isn’t it? It’s a tool, because at the end of the day, anything that makes you feel good is a positive thing. But cartoons are funny, aren’t they? You grow up with them; they’re the first thing you kind of know as a child. These talking animals were the people you loved to watch on repeat. They were your friends. As an adult, it’s completely mad to have a talking animal in your life. But as a child, they’re just normal to you. Talking squirrels, hilariously laughing ducks. At Iceberg, I love the cartoons. They’re not the entire brand, but they’re a nod to the history within all the other references for the collection. It’s almost a challenge every season to make them new, or to bring one of the characteristics of the cartoons into the collection and just have fun with it. When I see them used with fashion brands, it does look quite naive sometimes, but it’s so much a part of Jean-Charles, who was one of the first people to put cartoons on clothing. That seems like a mad concept, but that was his thing. As he was the founder of the brand, it would only be right to honor that part and then take it somewhere myself.

HL: What does creative freedom mean to you?

JL: When I had my own brand, it was like, there’s only me, right? There’s no one else telling you what to do. Your work is constantly your own. You’re not referencing a past, you’re just doing it. You’re working with someone, and there’s definitely going to be certain things that you want to do. When someone comes along at a fashion house, and you see them creating a new vision, as it grows and shows success, you see more of the personality of the designer coming through. That’s really all you have as a creative, your own thing that only you have. And when you see it coming through, it’s magic. You know when you see something and you think, “Oh, God, that’s not very free.” But you do know when you see something, whether it’s fashion or art, that feels pure and unadulteratedly creative. That’s the excitement of seeing creation.

In a world where we are drowning in a deluge of visualities, fulfilling our desire to be constantly stimulated, we easily forget sonic universes and their potentiality to contribute to experimental thinking. In what ways can we perceive the world as a soundscape composed of acoustic carriers that are charged with universal notions, instead of a mere optic environment? Intertwining sound and visual cultures, however, might lead us to a speculative state where we can hear images and see music.

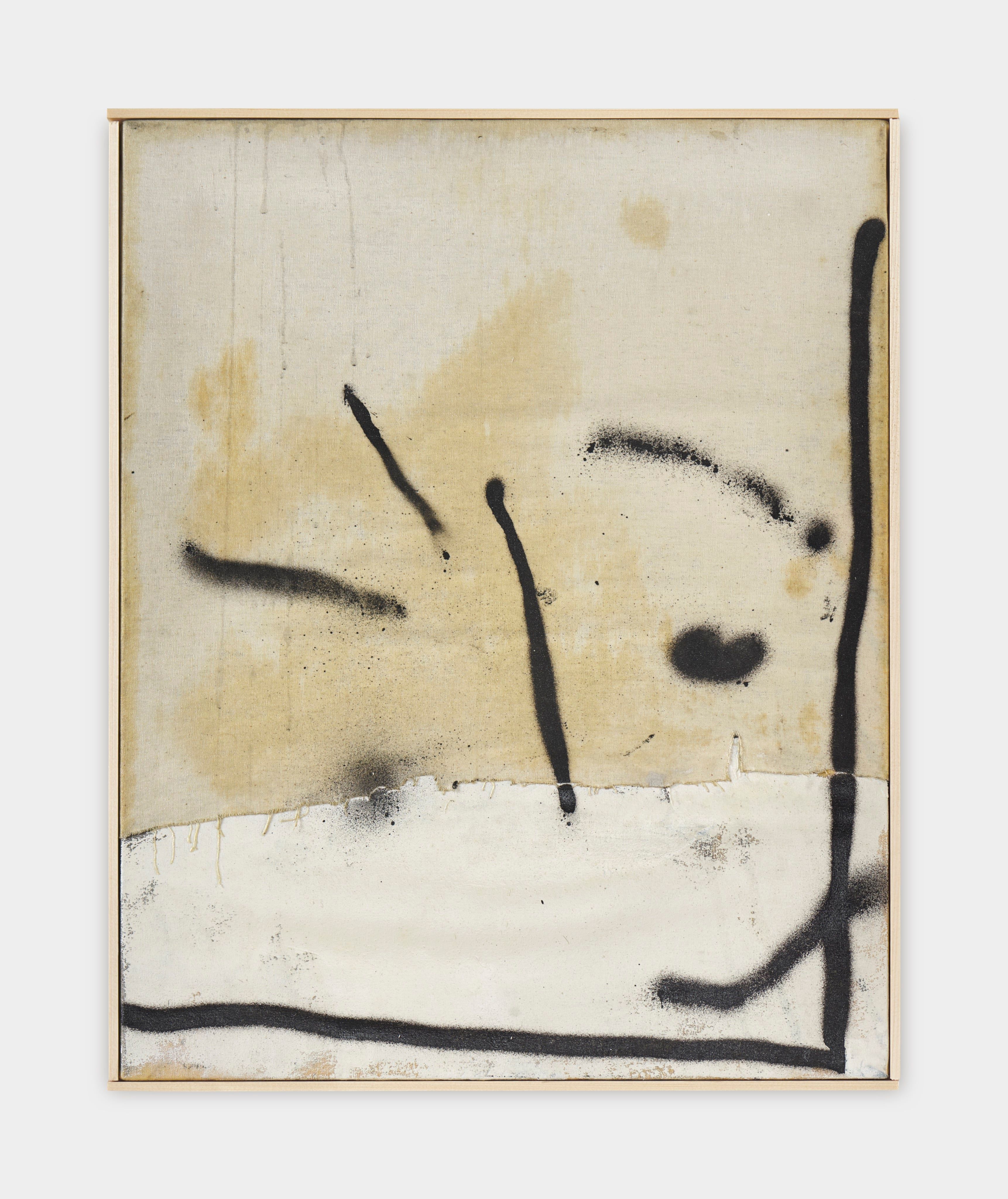

Artist Álvaro Guilherme and DJ Daria Kolosova are at home in these respective worlds. Guilherme is predominantly concerned with abstract painting, oscillating between imageries and writing poetry. Whereas Kolosova navigates the sonic materials of the electronic music industry.

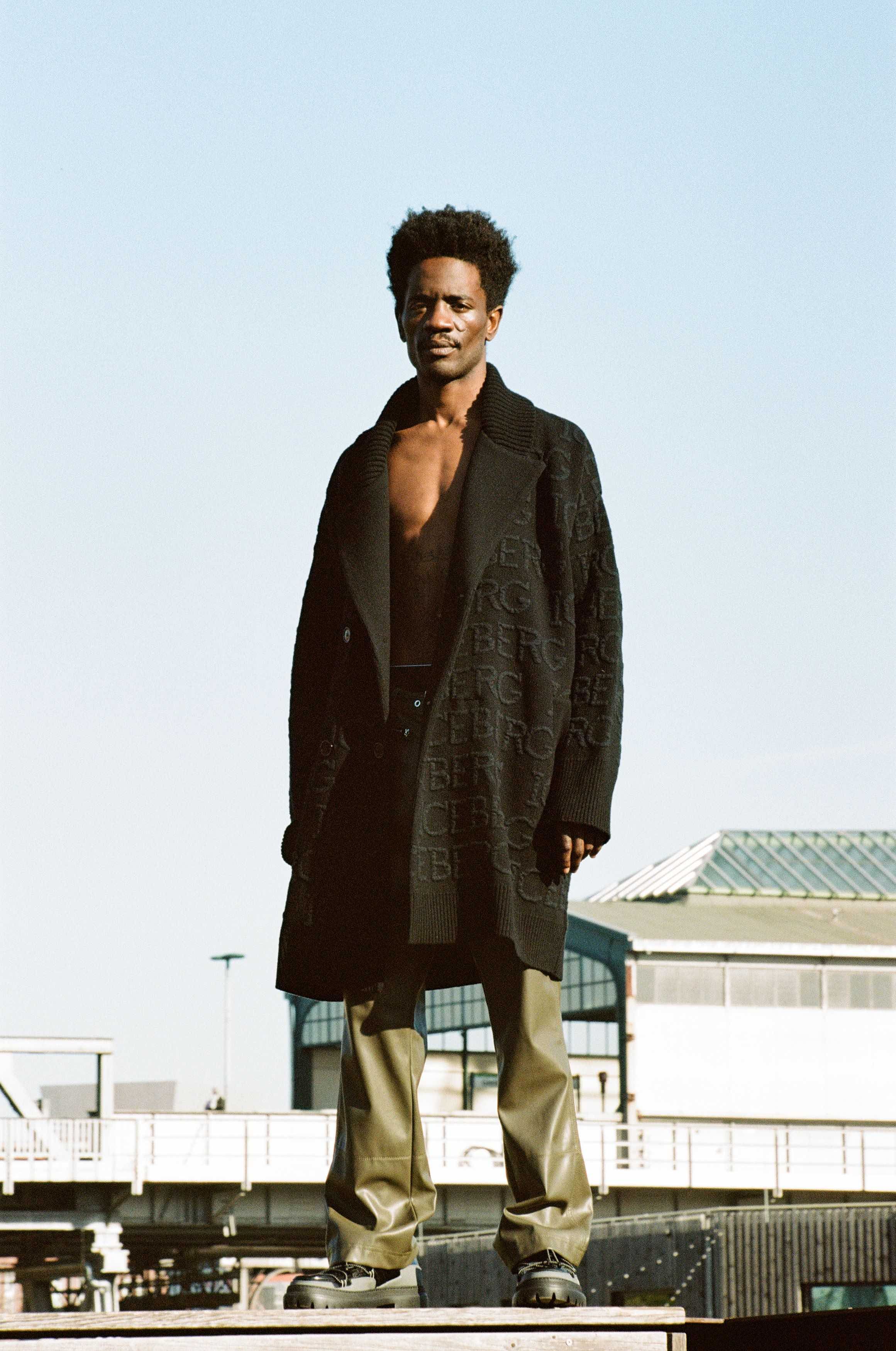

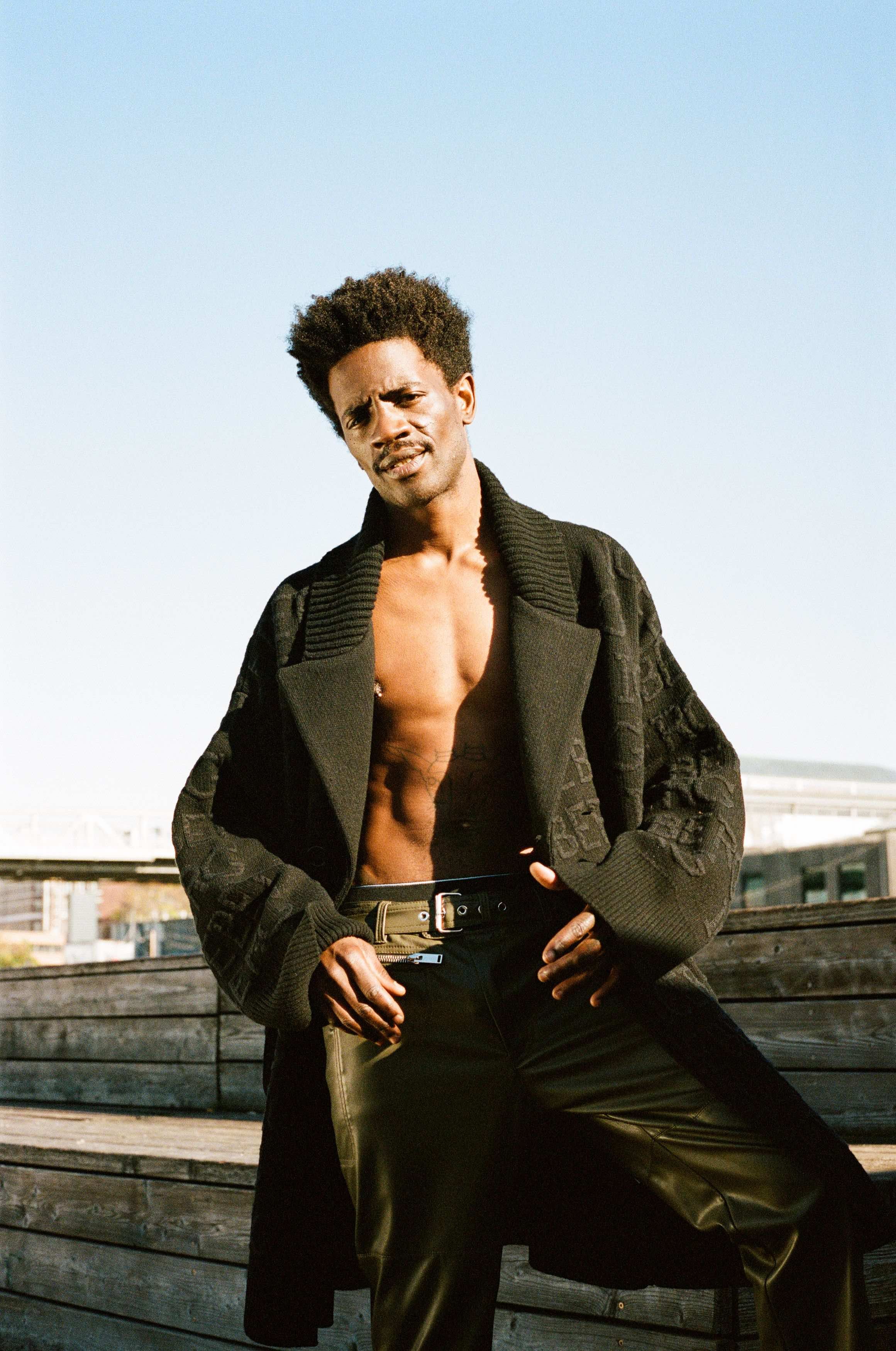

Photographed by Christian Werner and styled by Lucas Hübner, the two creatives experiment with the seeming discrepancy between sound and visuals through Iceberg’s FW-22 collection.

When I visited a solo show of yours last year in Berlin, you introduced me to the notion of Neo-Brut.

ÁLVARO GUILHERME: Yes. My idea of Neo-Brut is that it is a concoction of New-Brutalism —particularly, Le Corbusier’s influence on the movement — and art brut. It helped me to identify my work process at that time, because I was just constantly working. I needed a term to pinpoint what I was doing. It further helped me to set conceptual conditions under which my work could be created and be more reflective. I was always rather like an outsider. I have never studied art but was still introduced to it. The term helped me to materialize and conceptualize these personal conditions.

You have a quite nomadic way of creating your works, as you don’t work in a long-term studio, for example. You told me that you sometimes produce works in hotel rooms even. How does this aspect of nomadism and also restlessness affect your work

ÁG: I produce my works in many different cities, and I try to find inspiration wherever I am. But the works aren’t really different or change their cultural or visual language depending on the country I’m residing in at that moment. However, switching between different cities also helps me to explore different mediums. When I was in Belgium this year, I worked with sculpture for the first time. I started to be in conversation with some artists there, and suddenly I found myself in a ceramics studio.

Defining the term Neo-Brut is also a way of incorporating language into your practice. There are often words or arrays of letters scribbled onto your paintings, and you write poems. How do these poems or a more direct writing practice interact with your visual work?

ÁG: Writing, for me, is omnipresent. Writing is palpable in a textural way in my works, for example, through materials that protrude from the canvas, such as wood, that form letters or words. I think that a blind person should be able to decipher the work. I refer to my poems as science and laws in space. But if you call it poetry, maybe some poets will get mad at me.

You recently collaborated with a Japanese fashion brand. How was that process and what is the difference between working with people in fashion versus art?

ÁG: When I was in high school, I had these really amazing cowboy boots, but people back then didn’t like them. It was great to work with them because it reminded me of when I was a teenager — when I was 18-years old I dropped a series of handmade T-shirts. And since artists are performers, even participating in shoots, can somewhat be considered as part of my practice. But I also don’t want to constantly work in a commercial realm. Still, I appreciate the eclectic marriage that art and fashion have.

Is DJing a way of reflecting on the world for you, its good and bad aspects?

DARIA KOLOSOVA: DJing and music affects all aspects of my life. It has given me a lot of opportunities, for example, to travel around the world, be a part of a bigger cultural network, and grow my character.

I was born in a small city in Ukraine, and my family didn’t have money. Before I started DJing I had never been abroad because we couldn’t afford to travel. I always knew that I don’t want to live in my hometown, as there was not enough space for my ideas and personality. My first trip out of Ukraine was at the beginning of my career, and it made me realize that I want to learn more about the world and its different cultures — that’s when I knew that music is my passion. I have never seen myself as anything other than a musician. I’m interested in sharing this passion with others and thereby contributing to wider society.

However, there are also negative aspects that concern the industry, such as sleep deprivation, comparing yourself to others, sexism, racism, homophobia, and having to keep up a constant social media presence. Although I really respect electronic music culture, there are people who create snobbish conceptions of how DJs should look, how they should dance, and what they should play. Another toxic pattern in the industry is the expectation that musicians have to perform perfectly, no matter the circumstances.

Do you think you influence people’s lives in wider sense, going beyond the constrained space of a club, through your music?

DK: Music is one of the most potent tools on Earth — it accompanies us from the beginning of our lives to the very end. For example, from a mother singing a lullaby to her baby, to the music played at a funeral. Music is like therapy, and clubs function as safe spaces for this therapy. Music is even able to save lives in certain moments, and it can have a really positive impact on one’s mental health. I’m incredibly touched when I receive messages about how my set helped to turn someone’s bad day around or helped with their anxiety.

In what ways do fashion and design play a role in your work?

DK: It’s great to see that fashion now provides electronic music subcultures with an even more international platform. I’m thinking about collaborations such as Jeff Mills for Off White, Plastikman for Prada, or BFRND’s soundtracks for Balenciaga shows. It’s also interesting to observe that a certain rave aesthetic has been referenced by brands such as 44 label, A Better Mistake, Balenciaga, Vetements, or Ambush who even called their SS-23 collection “Rave.”

How does the styling for your performances affect your work? Do you intend to convey a message through the clothing you’re wearing?

DK: Though my personal style I’m transmitting my current state of mind. Like almost every techno DJ, I followed the all black trend for a bit, but I’m so tired of it. Now I simply follow my mood — sometimes I want to look casual, sometimes sporty, or I wear a fancy dress for a big techno festival. Comfort also plays a big role in my style. When I'm playing long sets in sweaty clubs, I want to wear comfortable sneakers and clothes that don’t restrict while performing. I’m trying to find balance between brands I like and what’s comfortable and practical behind the decks.

Credits

- Text: CLAIRE KORON ELAT

- Photography: CHRISTIAN WERNER

- Photography Assistant: MARYAM HOJJATI

- Fashion: LUCAS HÜBNER

- Hair and Makeup: MARVIN GLIßMANN

- Executive Producer: Kirill Rung

Related Content

BERGHAUS: Listen to ETAPP KYLE

DAVID OSTROWSKI Brings Bauhaus to Warsaw’s Galeria Wschód

CY TWOMBLY 1966

“Slowed & Throwed”: Exhibiting DJ SCREW

“The future has expired”: DIXON's Transmoderna seeks the spirit of the present

BLING BLING BRUTALISM: 032c Crystal Collection Launch Reception

Anti-Villa: ARNO BRANDLHUBER’s Thinking Model for a New 21st Century Architecture