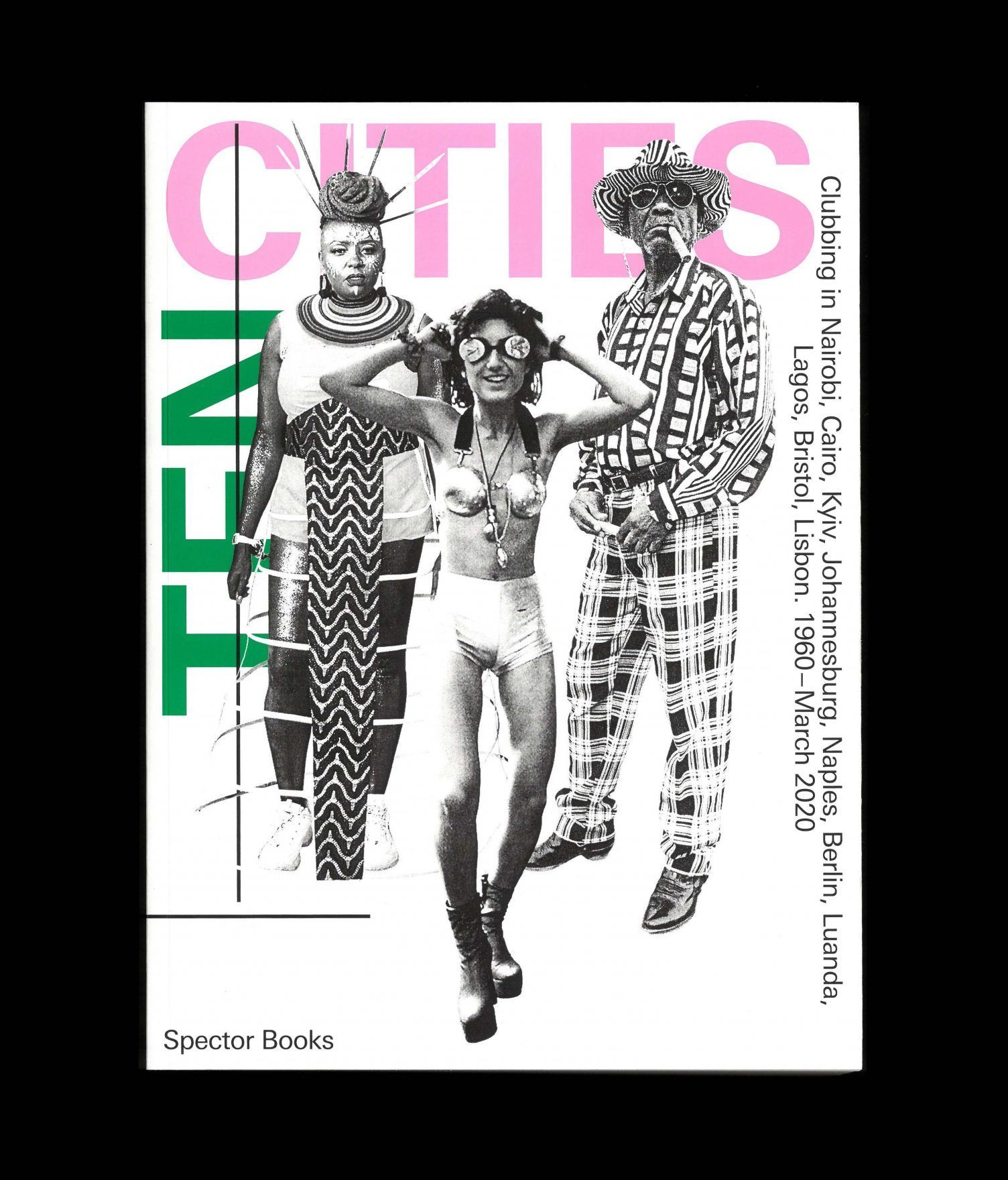

Ten Cities: Clubbing in Nairobi, Cairo, Kyiv, Johannesburg, Berlin, Naples, Luanda, Lagos, Bristol, and Lisbon (1960 – March 2020)

|Octavia Bürgel

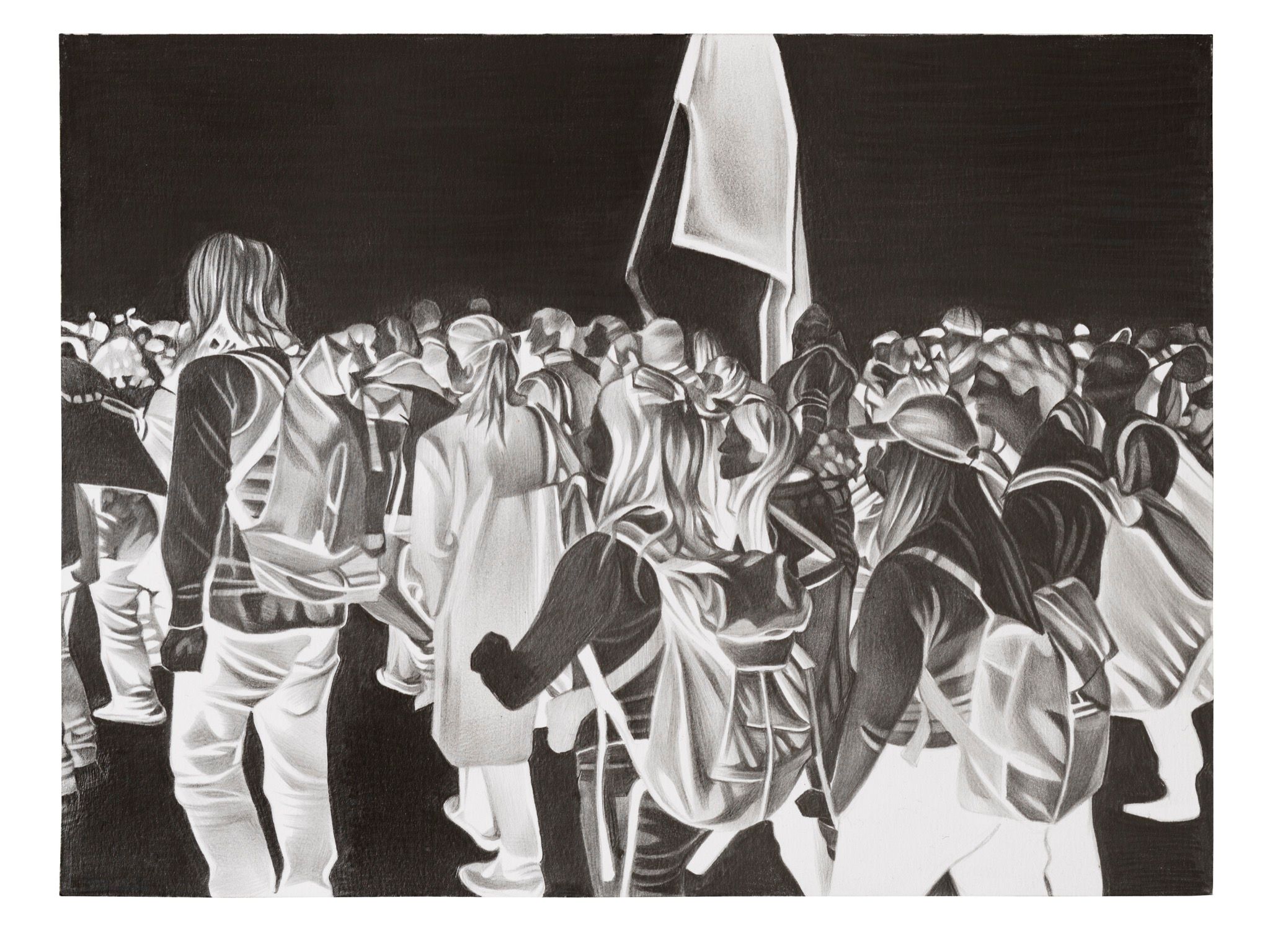

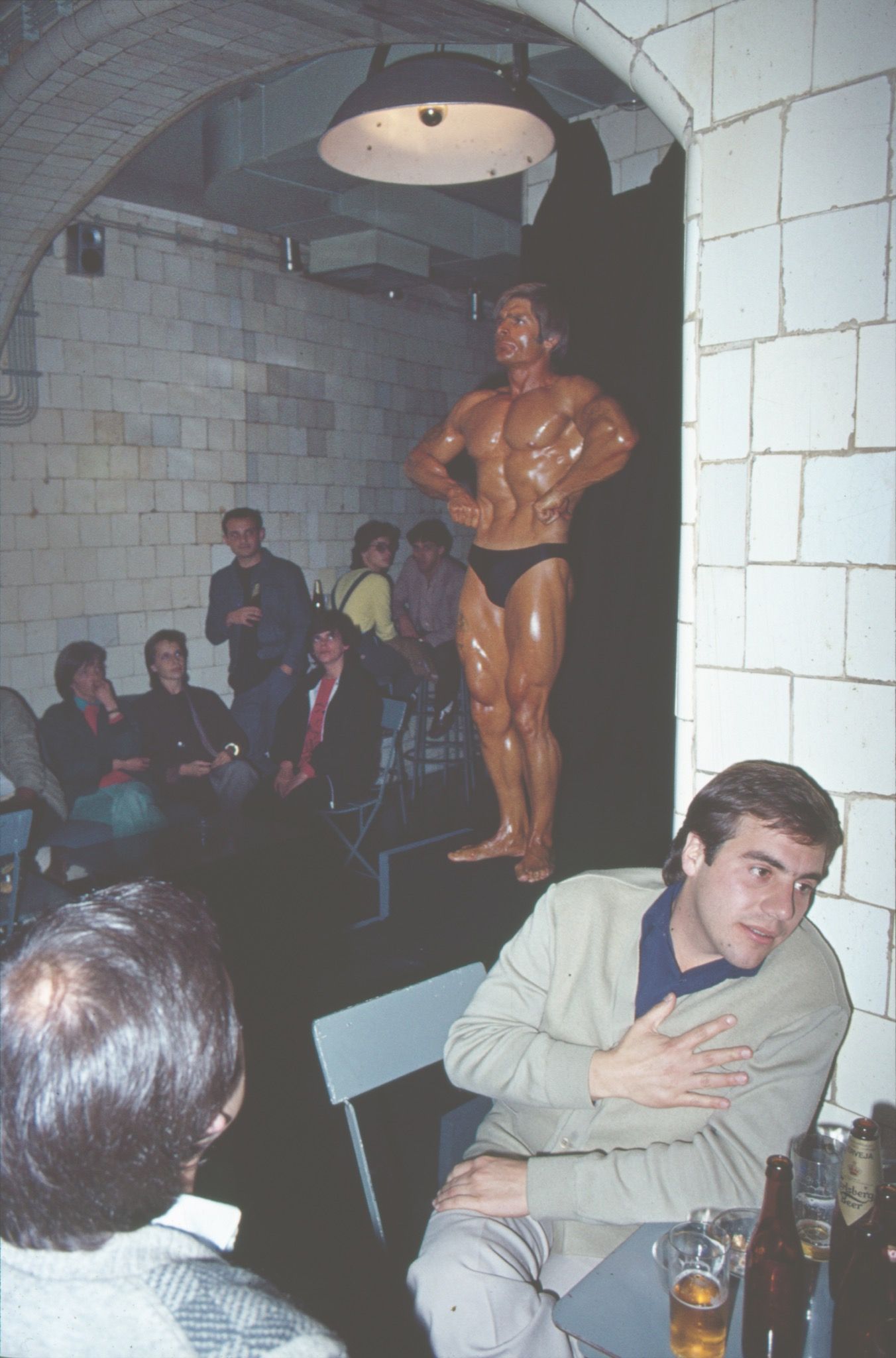

After a nine-month pandemic-forced closure, Berlin’s KitKatClub – known for its fetish dress code and encouragement of open sex – reopened as a Covid test center in December 2020. But KitKat was already a test site, because the club by nature is a testing site, capable of becoming whatever the community needs it to be. Clubs create “free spaces that can be laboratories for future societies, laboratories for experimentation with attitudes and ways of life,” Jonathan Ebert writes in Ten Cities, a tome that charts the global history of club culture from its under-acknowledged precedents in 1960s Africa to its defining influence in cities such as Berlin, where it has come in the last decades to “determine the mainstream.” KitKat’s pivot from public sex to public health proves Ebert’s point: you can take the nightlife out of the club, but the life of the club finds a way.

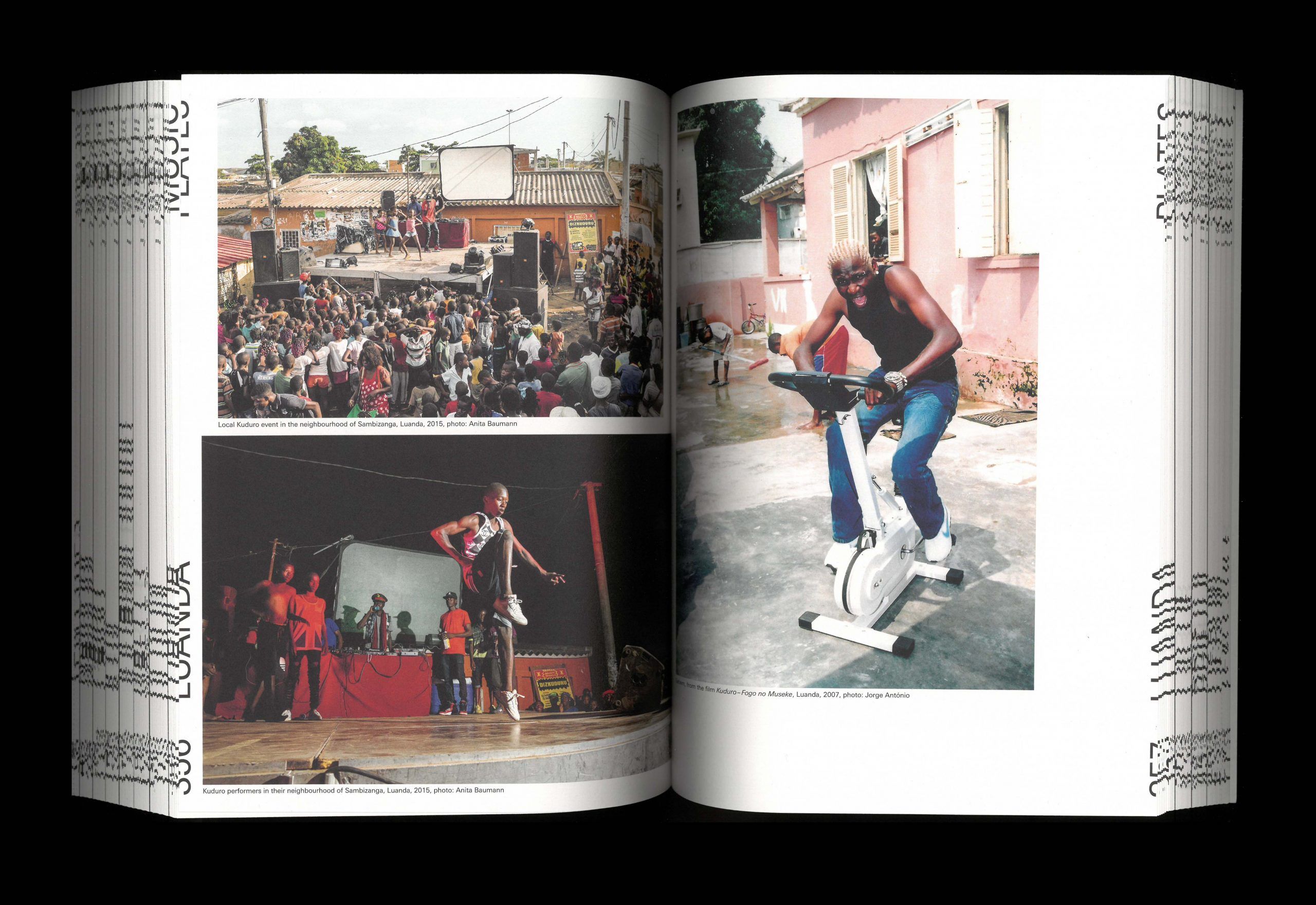

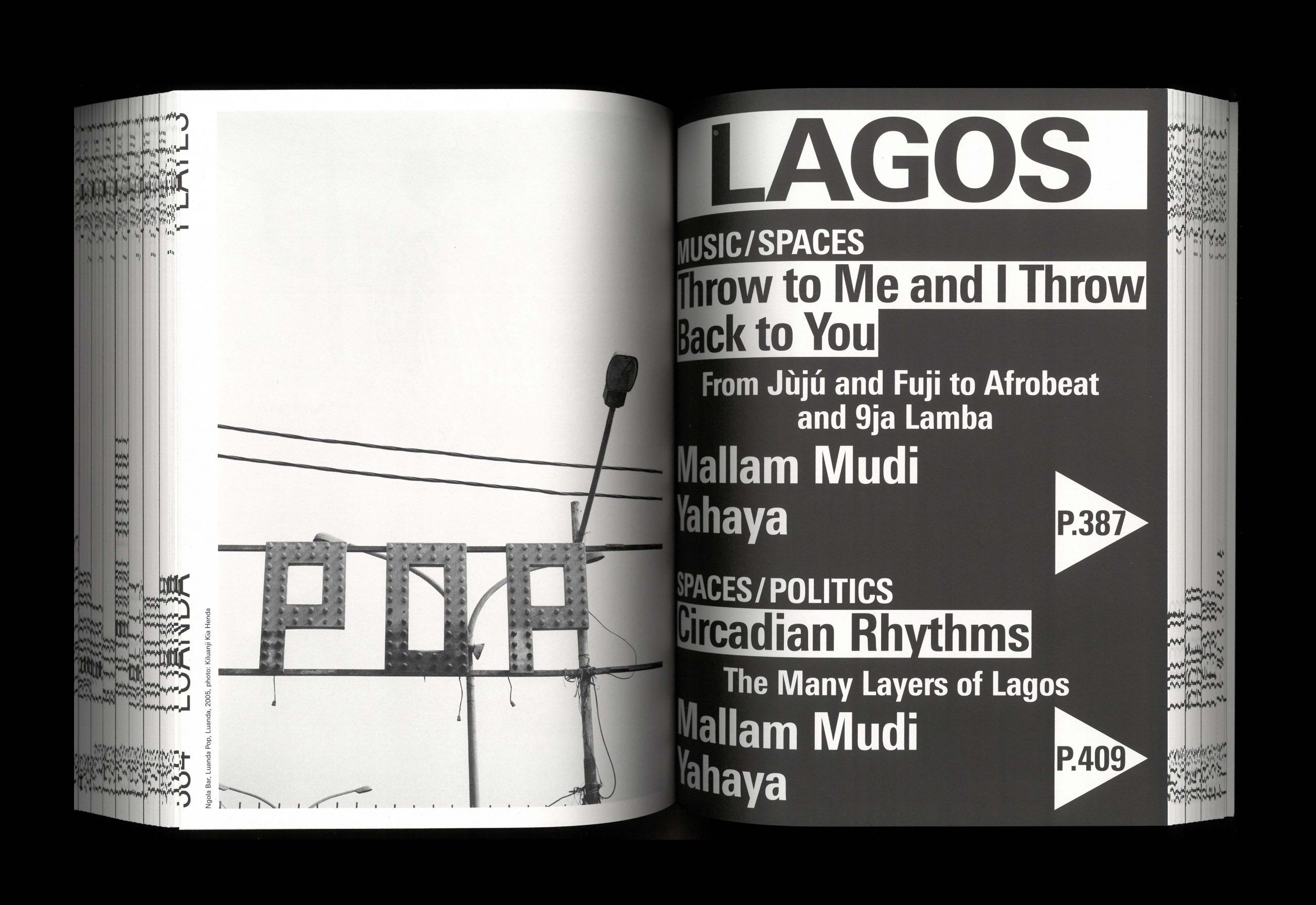

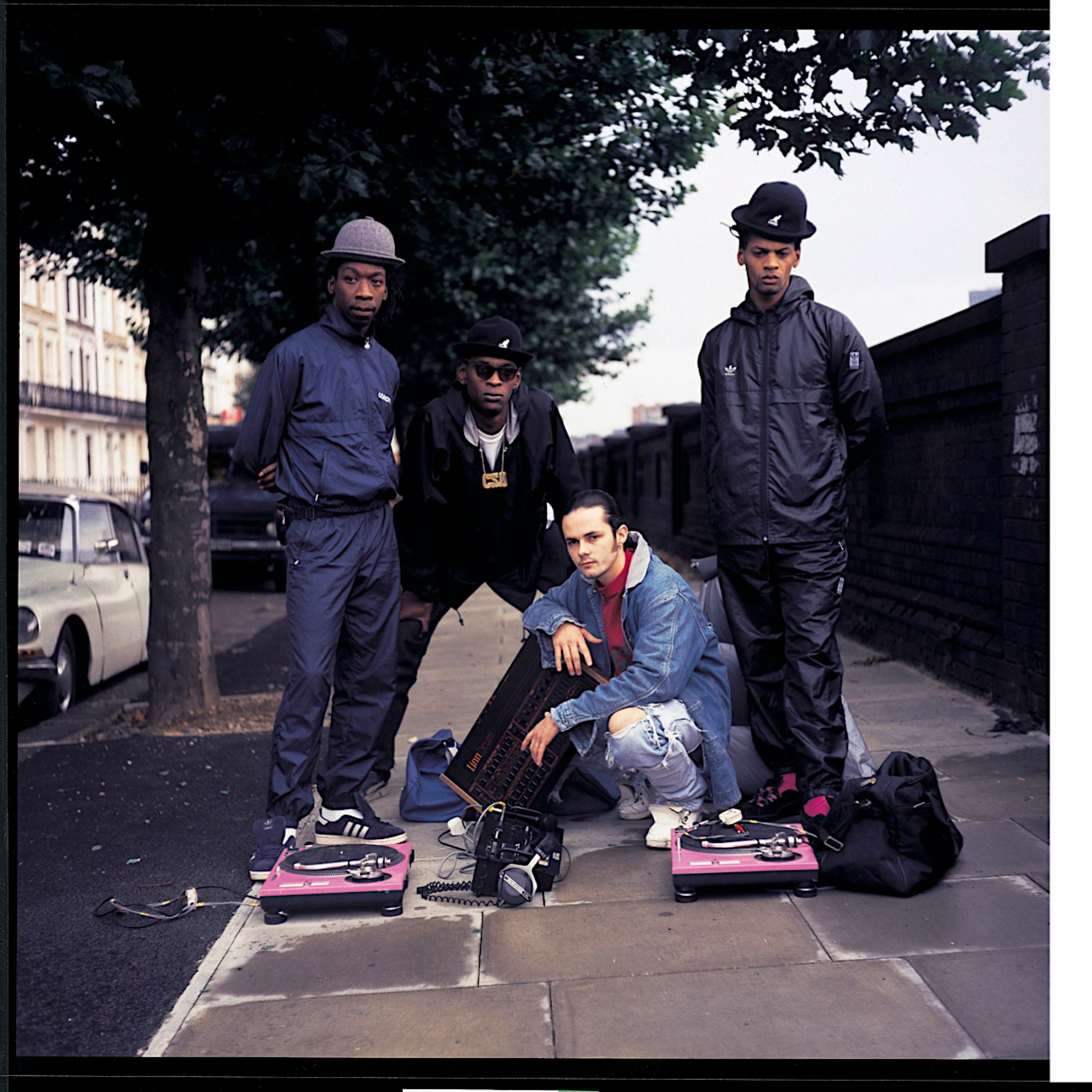

Ten Cities, like the subcultures it investigates, is disruptive, upending the dominant North Atlantic narrative that club culture emerged organic from cities such as Detroit, Chicago, Manchester, London, and Berlin. Published by Spector Books, the volume is the culmination of a multi-disciplinary project begun in Nairobi in 2010, which united producers from Berlin, Bristol, Cairo, Johannesburg, Kyiv, Lagos, Lisbon, Luanda, Nairobi, and Naples – 50 in total – in a “network of music and knowledge production” reflecting the rhizomatic and Global Southern nature of a worldwide scene. “African cultures have consistently added ideas, genres, and sounds into the global clubbing mainstream,” write Ten Cities’ editors, Johannes Hossfeld Etyang, Joyce Nyairo, and Florian Sievers. West African sounds – often erroneously blanket-termed “Afrobeats” – have certainly influenced contemporary pop, infusing high profile collaborations such as Drake and Skepta’s remix of WizKid’s “Ojuelegba,” and Beyoncé’s The Gift, the Lion King companion album that tapped artists of African origin alongside the likes of Kendrick Lamar and Childish Gambino. Still, despite Africa’s footprint on Western popular culture, the inverse impact remains most felt at home.

“Almost all of Africa today is a post-colony,” the editors remind us, positing the club as a means of exposing legacies of colonialism and power still ignored in the nations that perpetuate them. Appropriately, Ten Cities begins in 1960, when calls for independence rippled across the African continent, as youth cultures came to be recognized as global drivers of artistic, musical, political, and social movement. Its contributors oppose colonial control, and question the ability of westernized institutions – particularly their archives – to tell an accurate story. “Archives are sites for the performance of power,” the editors explain, “the power to determine what is remembered and what is forgotten.” Ten Cities seeks authenticity in alternate sources – oral histories, for example, and hidden repositories of printed matter and recorded sound. But in seeking to build a “monument to forgotten histories,” the authors must be careful not to institutionalize themselves: don’t view this work as complete of final, they urge the reader, “and certainly not as official and canonical.”

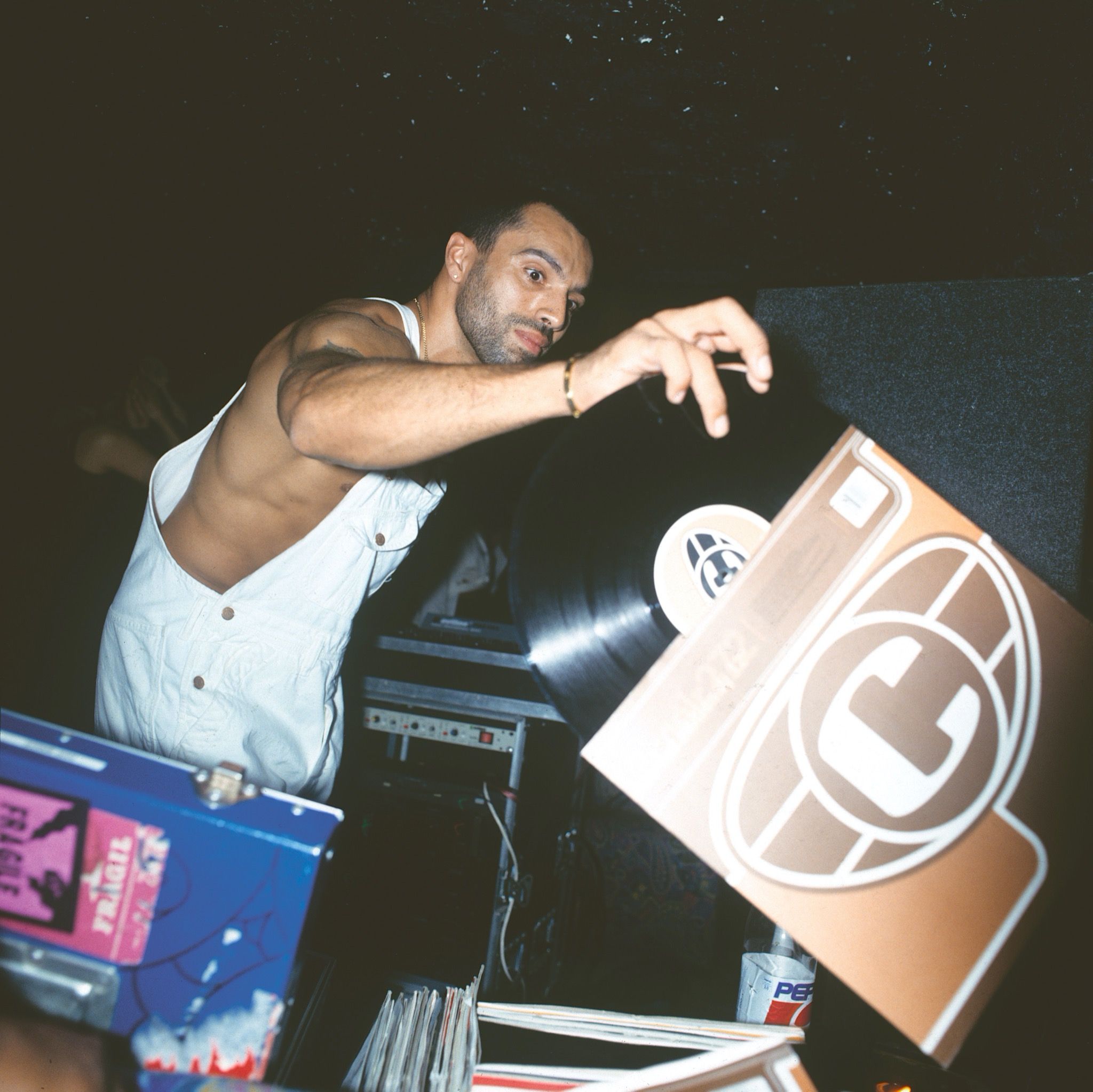

In the post-Covid landscape, artists and thinkers have called for new institutional models, the crisis having revealed how poorly built established systems were. Yet “new institutions” contribute nothing if they mimic the values and structures of old ones – and they almost always do. Keeping things unofficial, incomplete, or off-the-record are strategies that avoid calcification. Maybe that’s another reason for clubs’ “no photo” policies: to resist, or at least to slow, canonization. “Club cultures may be strongly referential to the past,” reads Ten Cities, “but at the same time they are ephemeral – of the moment, of experience in the here and now, often also of the secret life.” Any KitKat regular would agree: the club is to be experienced, not documented.

Credits

- Text: Octavia Bürgel