Design with a Social Mission: Paulin Paulin Paulin

|Claire Koron Elat

“Luxury is vulgar. True beauty lies in things everyone can use” – Pierre Paulin

Benjamin and Alice Paulin

Pierre Paulin’s vision of design as a social mission—democratic, functional, human—still remains at the core of Paulin, Paulin, Paulin, the studio founded by his son Benjamin and his wife Alice. Far from nostalgic revival, their work reanimates Paulin’s modernist ideals for a contemporary audience through collaborations that go beyond furniture. From re-editions of iconic pieces like the Groovy and Dune chairs to limited capsule collections and the experimental Sounds Like Paulin music initiative, the studio continues to blur boundaries between design, art, and sound. Yet its spirit remains faithful to Pierre Paulin’s belief that design should serve rather than dominate; a philosophy that, decades later, feels more relevant than ever.

Favored by the likes of Travis Scott, Frank Ocean, Hailey Bieber, Kourtney Kardashian, and others, Claire Koron Elat talked to Benjamin Paulin in their studio and house in Paris about conservation versus reinterpretation, hating luxury, and turning furniture into music.

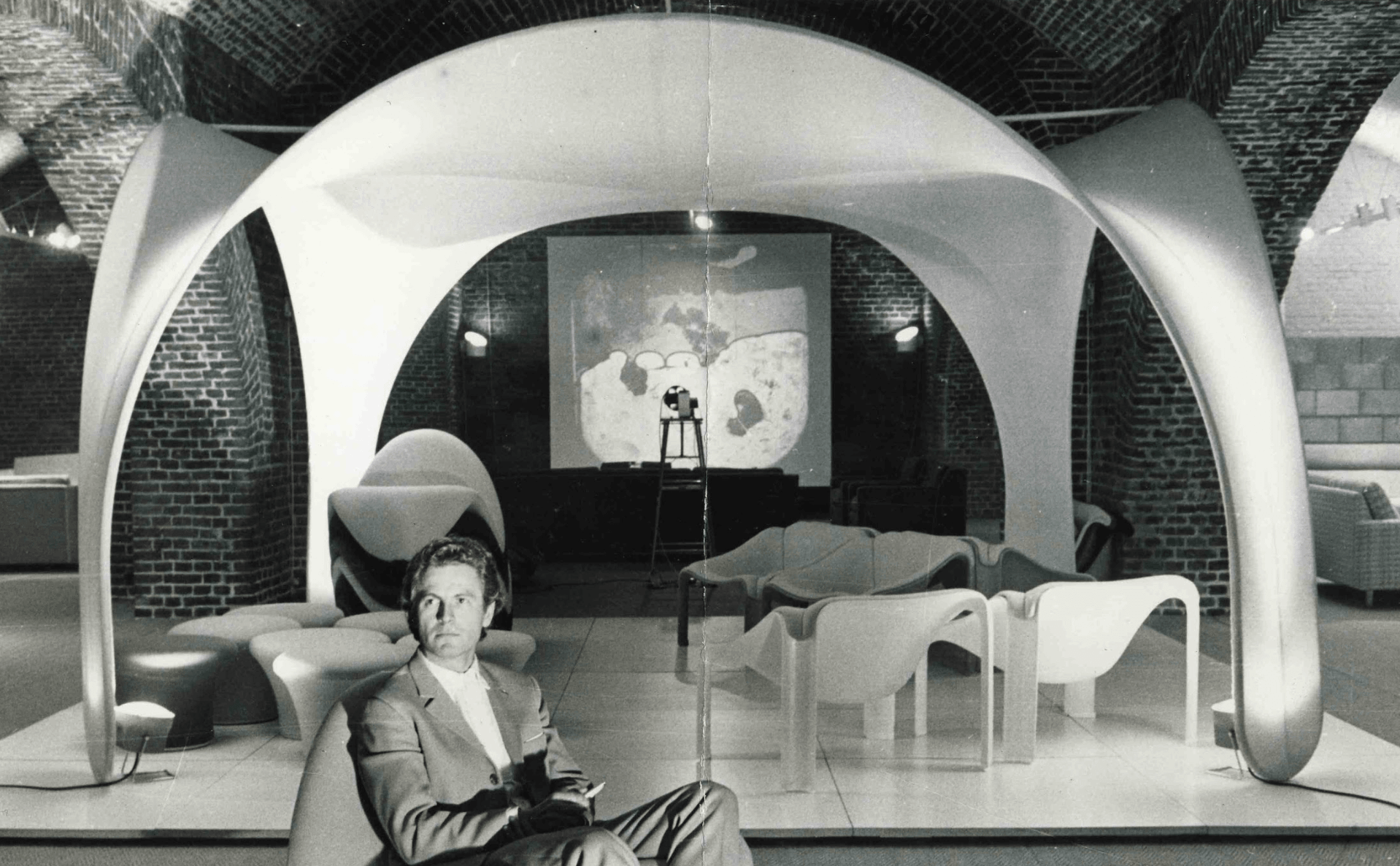

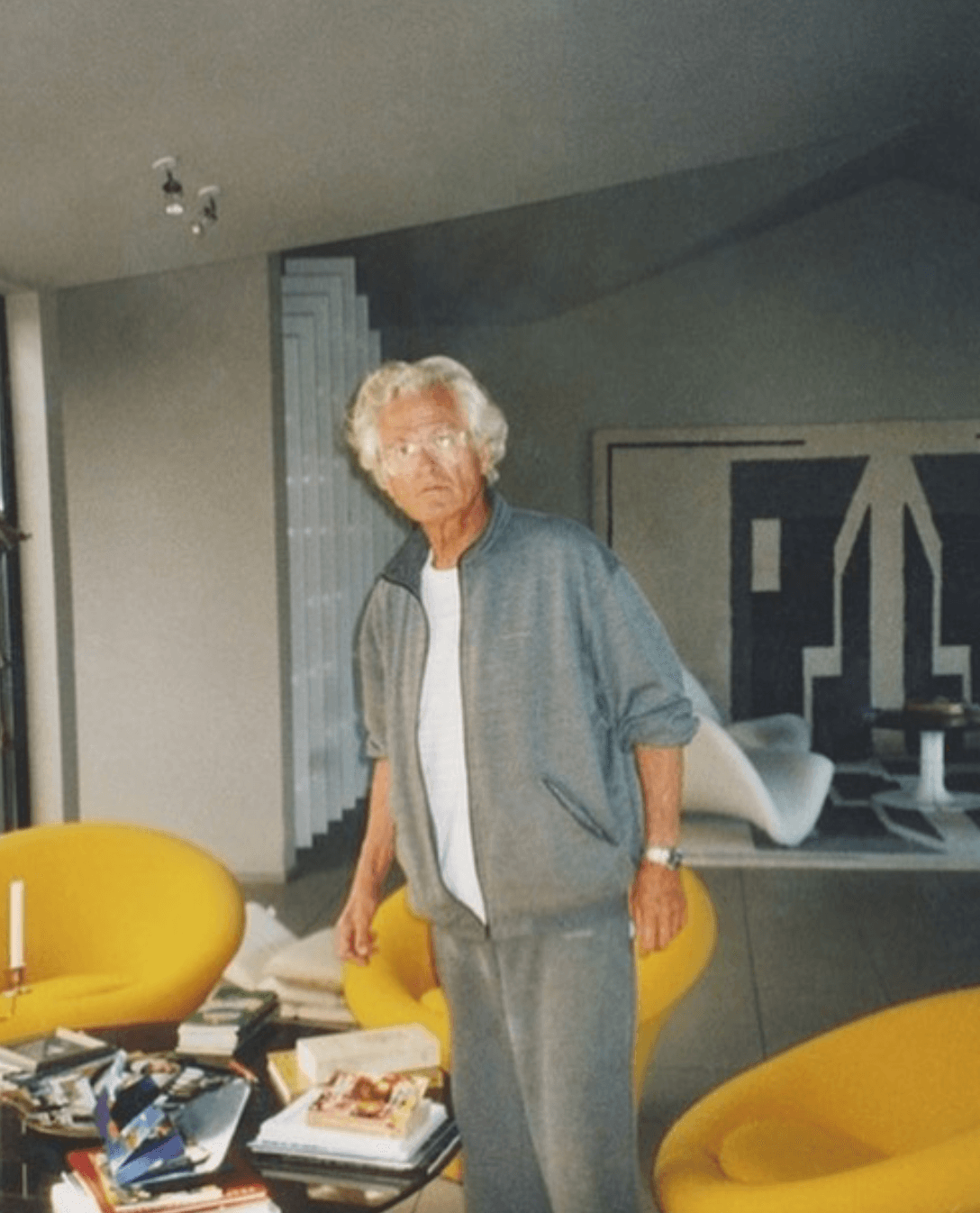

Pierre Paulin in the late 60s

Claire Koron Elat: How does your specific design philosophy resonate with contemporary design culture at large? And how do you position yourself within contemporary design?

Benjamin Paulin: It’s kind of easy to position myself, because my work is based on my father’s design. We are primarily working with this functionalist era, but also through the pop era. My father considered himself to be sort of the end of functionalism, also because he was discovering new material possibilities with stretchy fabrics, pirated foam, and other new developments that were possible. To me, the biggest difference between my father’s generation and the design nowadays would be that my father’s generation absolutely did not approach design from an art angle. They did not consider themselves to be artists. They considered themselves to be serving. It was after the Second World War, a moment where designers were on a mission to improve the world, at least in Paris.

My father’s generation was trying to improve the lives of people and approached design with a very social perspective. I have the impression that a lot of artists today are using design as a medium. I’m of course not very objective, because I’m totally following my father’s vision and legacy.

CKE: Would you say that you don’t see design from an art angle at all?

BP: My father had an interesting saying: Artists should be wolves, because they are against everybody, and they have to bring a vision to the world. They cannot do something that is pleasant. They have to create a shock. On the other hand, designers should be dogs, because they are serving and have to respect a lot of details. Can you really pretend to be a wolf when you are actually serving? That’s the question. From this perspective, it’s impossible to pretend that you’re making art, but you can, of course, have a very artistic sense. It’s more of a decorative art vision, not pure art.

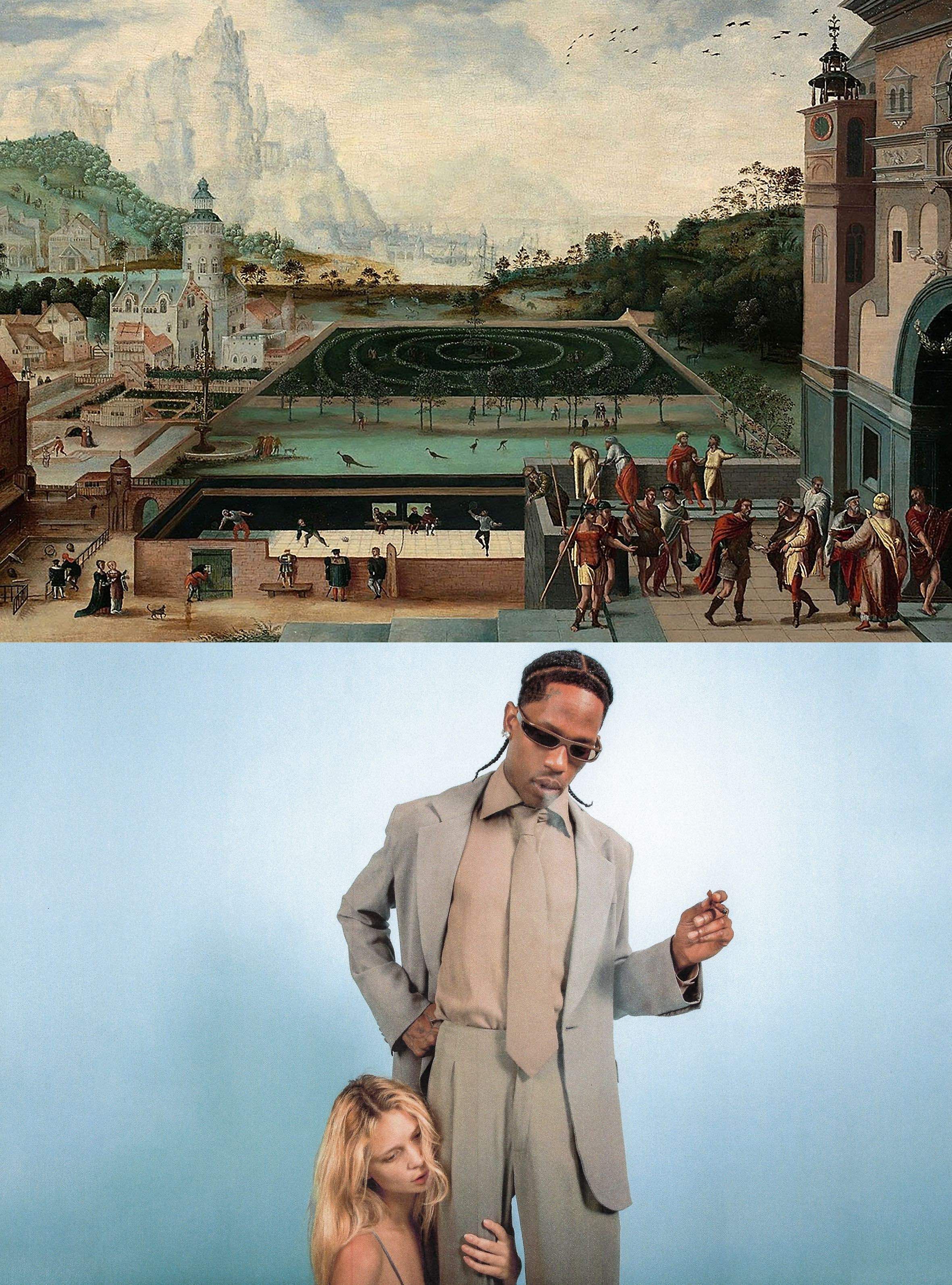

Travis Scott and Steve Lacy

CKE: Your work is about preserving and developing your father’s work. How do you distinguish between conservation and reinterpretation?

BP: Since the beginning, I’ve really tried not to make any alterations; to be as close as possible to all of my father’s intentions, without any interpretation. We think of our work as creating contexts to tell a story in a way that connects with new generations. But we’re also slowly accepting the idea that we can change a bit. For example, we installed a sound system in one piece. My father’s initial idea was to build the sound system around the piece, but when we developed it, we wanted to put the sound inside without changing anything about the design. I don’t consider myself to be a designer here. We just wanted to improve it without changing the aesthetic.

CKE: The re-editions that you just launched are meant to be more widely accessible. Why did you decide to do that?

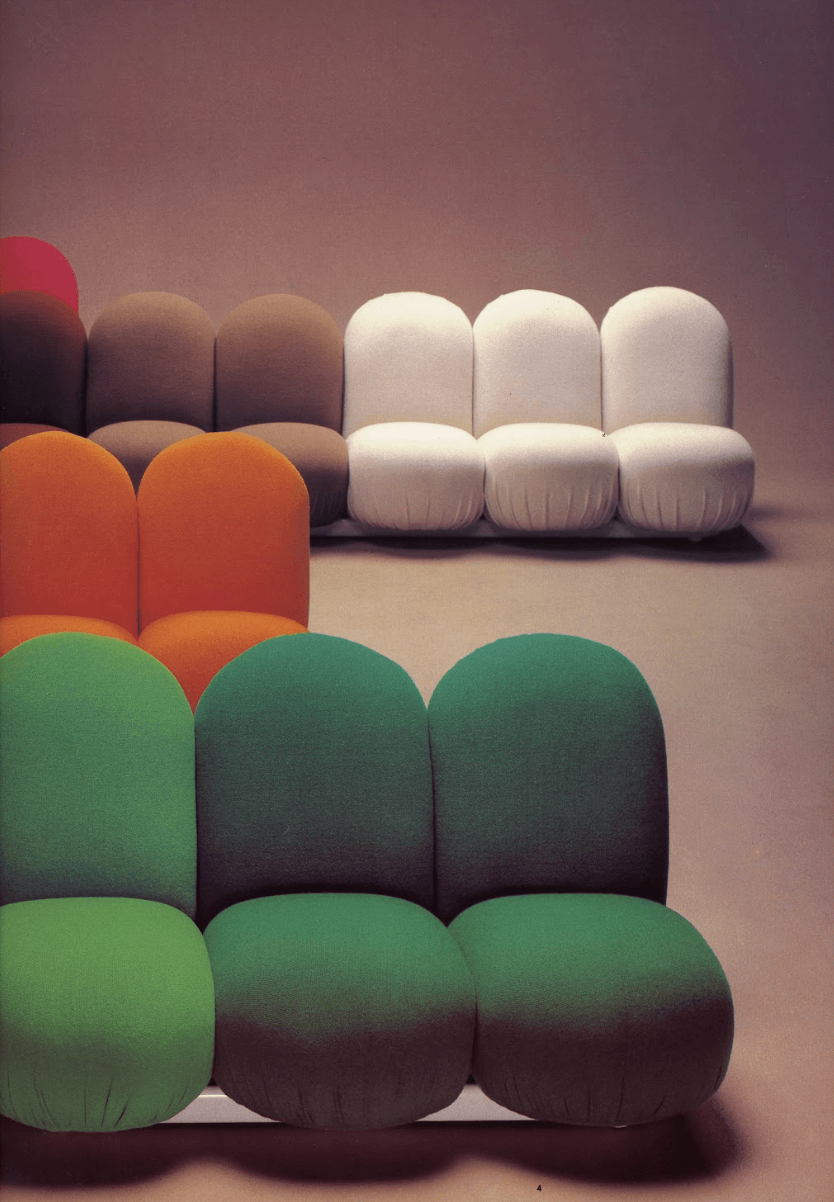

BP: My father hated luxury. He hated the bourgeoisie and their kind of vision of the world. He wanted everybody to have access to his designs. If I could do everything for free, I would. But this is not the world we live in. We started with the edition of impossible pieces, like the Decline, the Dunes, and the Tapis-Siège. All those pieces as well as the rejected ones—the pieces I grew up on that were rejected by the industry because they were not adapted to a more global market. My father kept them as prototypes.

When I started, those pieces were totally unknown, but now so many people have seen them and want them. The way we produce is very artisanal because my father never developed it industrially. It’s the work of a workshop. We produce each piece very carefully but without any industrial intentions. Paulin, Paulin, Paulin is in the ongoing process of preserving Pierre Paulin's legacy. To make this ambition happen, we began by producing so-called “utopian” pieces such as the Dune. The utopia pieces are so named because they were my father’s dream. A dream that he never managed to realize. The challenge with these pieces is that their production is very limited (one unit per week in Les Cévennes), and therefore they are not widely available.

Unlike these rare Utopic editions, the re-editions are produced at a larger scale, with the goal of making Pierre Paulin’s work more widely accessible while staying true to the Paulin, Paulin, Paulin DNA. For the Paulin family, it’s a way of reclaiming our heritage while expressing our vision of Pierre Paulin’s legacy.

In the last ten years, we have received many requests from people, brands, public spaces, hotels, and the like that we have rejected because we thought we couldn’t do it. We produce so few pieces that we cannot sell them to public spaces. It’s not adapted to their needs. It was very difficult. And it was also very frustrating for everybody who asked us because we looked very snobbish. We felt bad because we have to say no to everyone.

And then we thought about all those pieces that were produced in the 60s and 70s, such as the Groovy Chair (1964) or the Tounge Chair (1967), which my father actually developed as industrial products until the industrial companies lost a bit of their working force and they stopped producing them. We decided to do those models and create them on the side of our main additions, thereby solving some of the problems we were facing.

One problem was the frustration of the people who were not able to access our pieces. And then our frustration in not being able to sell anything to them. Another frustration was that, in the last ten years, we slowly took over the vision of the Dunes and the Tapis and all those pieces that were so powerful that they kind of made everything else by Pierre Paulin invisible. It’s important for us to explain the importance of the designs he created in the 50s, 60s, and 70s, and that they changed the design world. He opened up new possibilities with all those organic shapes that were impossible before the technical capabilities. That’s why we started this edition. And we also want to open the door to young people, for example. Also, not everybody has a big house, and so they maybe just want a chair for the living room. It’s not our intention to only sell to a few people who can afford it. It’s like the malediction of the utopia because those pieces are really expensive to make.

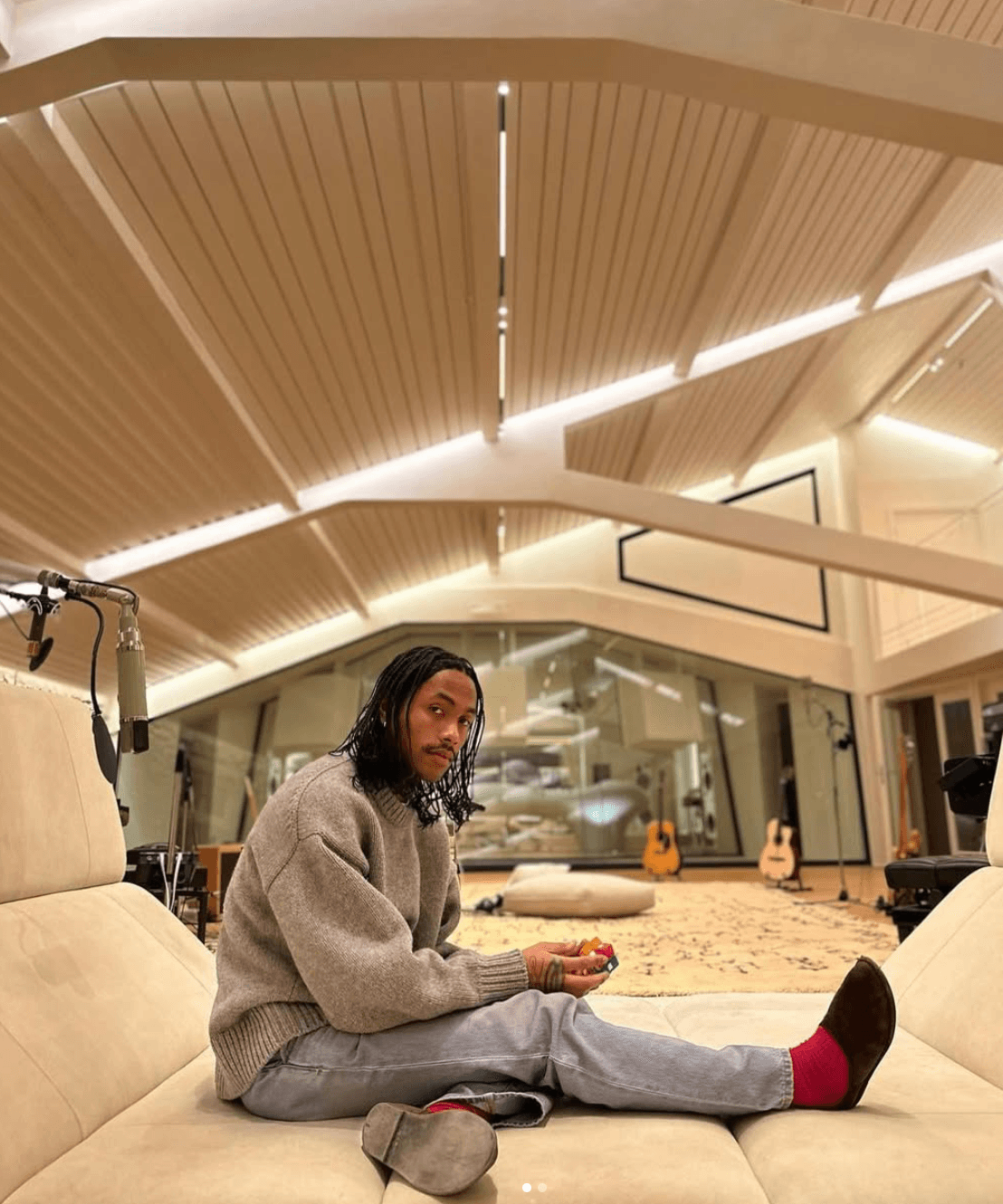

Pierre Paulin, 1990

CKE: Did making those pieces available online change the relationship that you have to your audience and collectors? Because there are, of course, some collectors who really value exclusivity.

BP: This collection is available at Le Bon Marché in Paris and will probably also be available in some selected boutiques in America and on the website. But, you know, it’s a development process. We don’t have millions of sales on the website. At the moment, we are still a very small company. Everything is managed by Alice and me. People have these fantasies about the furniture business, but when you look at the numbers, they are shocked. We are still babies—and we are also too kind for this business. But we’re trying to understand it better and develop.

CKE: You also launched a capsule collection of T-shirts, which is an interesting extension. How do you see the worlds of design and fashion interacting, specifically in your work?

BP: Again, it’s our intention to create connections with our community. Because we have a lot of very young people, like 15-year-olds or people in their 20s, who discovered us maybe through a musician. Those types of products are part of a conversation we want to create. That’s because we don’t expect them to buy a Dune sofa. But it’s part of creating a community.

CKE: Earlier you said that you’re still a pretty small company. Do you see yourself expanding in the future?

BP: I’m afraid expansion is the only way. But it’s all about your intention. And ours is not to become a big industrial brand with like 200 people who work in shops all around the world. My father’s vision was more than just objects. We took the vision he applied to furniture and transformed it into the realm of music. We started a music label and are already recording many projects.

It’s not only about producing and selling furniture. That’s just one thing. I don’t have the ambition to sell more. We want to develop. Paulin is a project. Sometimes it can be a bit confusing depending on who we’re talking to. For example, museum directors often think we’re a brand. And we’re like, “No, we’re not a brand. We are a foundation.” That’s why we’re now creating different branches of the project. For example, there is one attached to the collection we created in the last ten years. We bought around 350 of my father’s very important pieces from galleries, auctions, and the like. The idea is to build a museum that will open in 2027. So, part of this is also building relationships with other museums. And then of course there’s Sounds Like Paulin. Part of this project could be an album, but also a concert, an installation, or anything that fits into the aesthetic and philosophy of Paulin. And then we have Paulin, Paulin, Paulin, which takes all of this over, but also produces the furniture to keep everything alive.

Credits

- Text: Claire Koron Elat