1968: Italian Radical Design

In today's media landscape, a book review is often a slap on the back. A handshake among colleagues that says, “well done.” But we have never been afraid to offer critique when critique is due. In our print section Berlin Reviews, we've always tried to take the propositions of a book seriously and push them to their extremes.

Archive Berlin Review from our issue #27.

“Utopia was born and died in that same year,” recalls Greek collector and patron DAKIS JOANNOU of 1968. He was in Rome at the time, studying architecture, and has since amassed one of the most comprehensive collections of Italian furniture from that era. For 1968: Italian Radical Design, Joannou has allowed MAURIZIO CATTELAN and PIER PALOFERRARI of Toilet Paper to run wild through his collection in a Playboy-style tribute to a year cultural upheaval.

Design had its share of mutinies in the late 1960s, directed mainly towards the modernist masters of recent decades. With their reprisals of European design classics, Knoll had turned Bauhaus into the international language of the boardroom. Minimalism had become an establishment, and its attachment to the imperatives of function posed an existential threat to the possibility of new design.

An answer eventually came from Tuscany, where studios such as Superstudio and Archizoom had been experimenting at a safe distance from the architectural epicenter of Milan. Announcing their arrival in a 1965 issue of Domus, Archizoom proclaimed: “We want to introduce you to everything that remains out of the door: fabricated banality, intentional vulgarity, urban furniture, voracious dogs.”

The result was a riot in the living room, a leopard-print grenade thrown at the citadel of good taste. With the endorsement of its mentor Ettore Sottsass, Archizoom and its contemporaries developed a masterful command of the absurd. Quoting freely from American pop, Italian radical Design was a lavishly decorative counter-proposal to the “less is more” aesthetic. Yet, like many things 1968, the party was short-lived. What remains now is a fever dream.

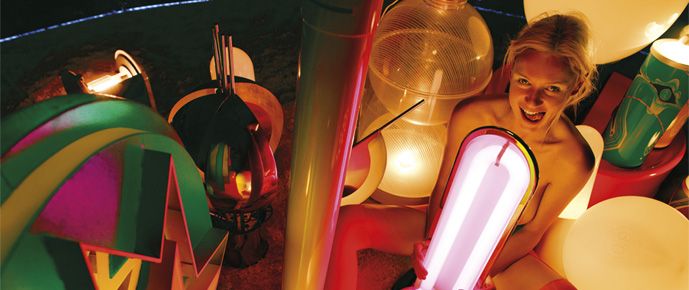

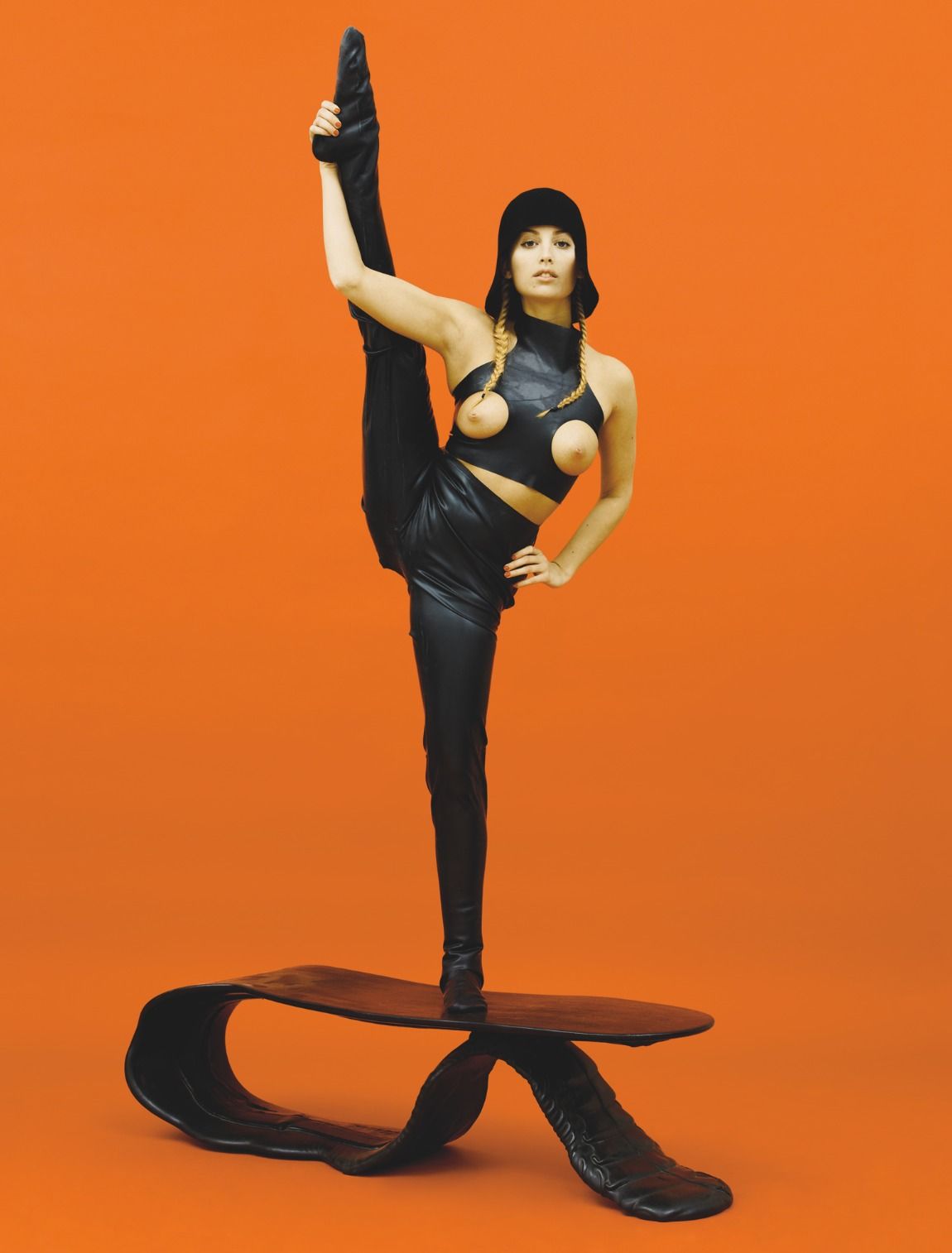

1968: Radical Italian Design is a demented afterparty to end all after-parties. The book pictures a model pissing onto a Vittorio Introini desk, an anonymous hand cracking eggs onto an Ettore Sottsass dining table, and a Christian Germanaz chair covered in spaghetti pomodoro. Taking cues from Hugh Hefner and Austin Powers, these scenes of debauchery spill onto their sensual and psychedelic backdrop, at times stealing the spotlight from the artifacts themselves. In one spread, the coy blond sitting in a room full of lamps by Sottsass and others is listed instead of the furniture, crediting her parents: “Natalia N By Elena and Igor N.” The caption studiously includes dimensions for her hips, waist, and bust.

By paying homage through irreverence, Toilet Paper’s 1968 resuscitates the countercultural energy of an era – giving history the sex it deserves.

1968: Italian Radical Design is published by the DESTE Foundation and Toilet Paper (Athens, 2014).