Golden Teachers: Can Mushrooms Save the World?

|Francesca Gavin

“Mushrooms: The Art, Design, and Future of Fungi” opened at London’s Somerset House last month. The institution has announced that it will be closed until May 1, 2020, but we can still learn from mushrooms, says the exhibition’s curator Francesca Gavin.

“At a moment of closed borders, separation, and fear, the mushroom becomes something we can look at to recalibrate. Without mushrooms all ecosystems would fail. Thousands of plants and trees cannot absorb water or nutrients without mycelium intertwined with their roots. Mushrooms are a metaphor for our need to live symbiotically in tandem with nature. They point to a new way of structuring society, not as individuals but as a network that needs to live in collaboration. There is a political and technological angle here. The creator of bitcoin was allegedly a mycologist and its structure is based on that of fungi. In a more direct way, the physiological and psychological relationship of human beings is fundamentally shifted by the mushroom. Fungi are a vital part of our microbiome, which enable our bodies to flourish. Psilocybin can also have dramatically positive and lasting effects on the human psyche, something scientists and researchers are taking very seriously in recent years. Foraging itself could be seen as a meditative practice – the discovery of mushrooms can be a peaceful process of connection. Mushrooms can having last effect on pollution, chemical waste and possibly even consume plastic. It is not without basis that people are questioning today – can mushrooms save the world?”

– FRANCESCA GAVIN

Introduction to the catalogue Mushrooms: The Art, Design and Future of Fungi published by Somerset House:

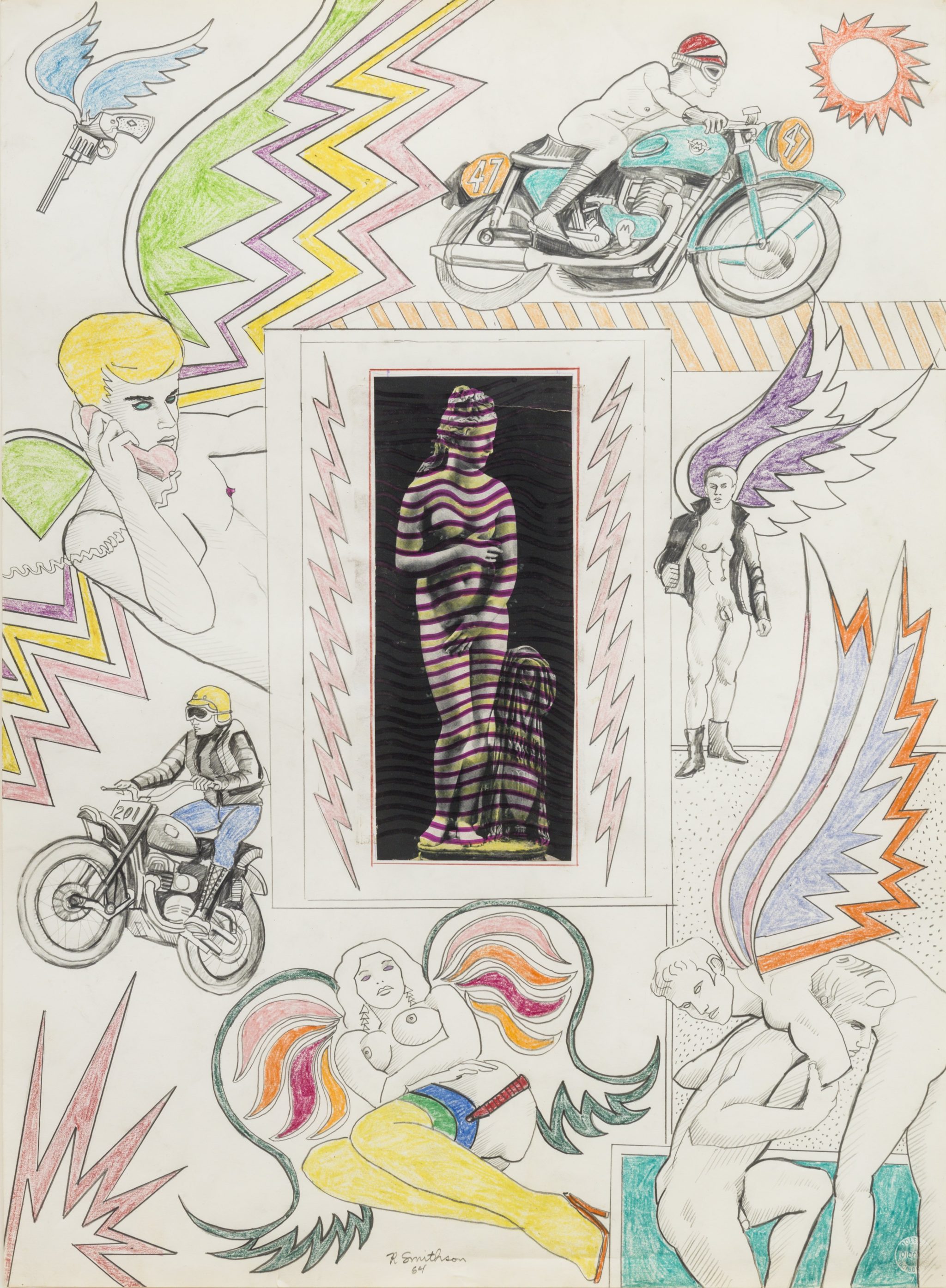

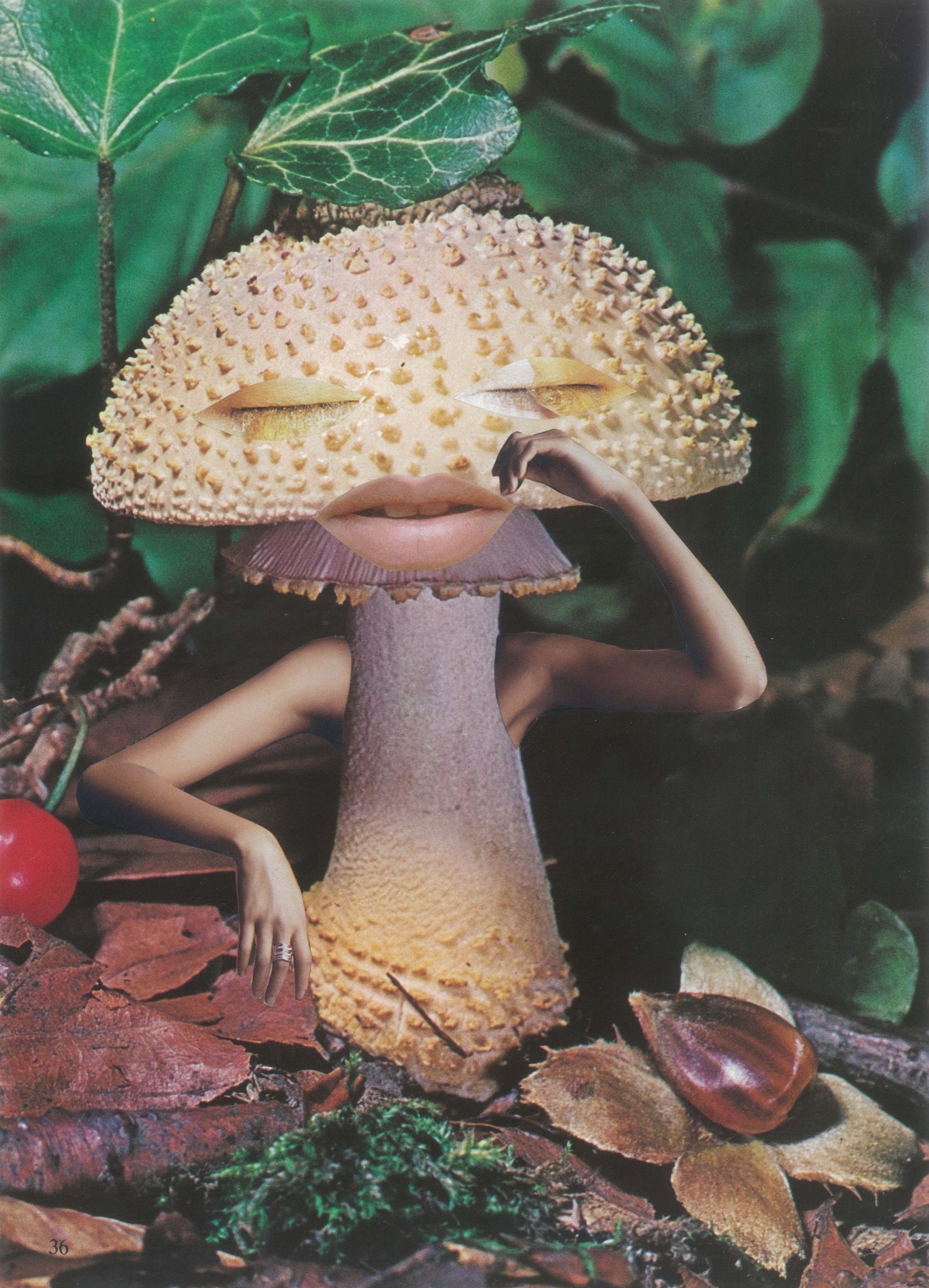

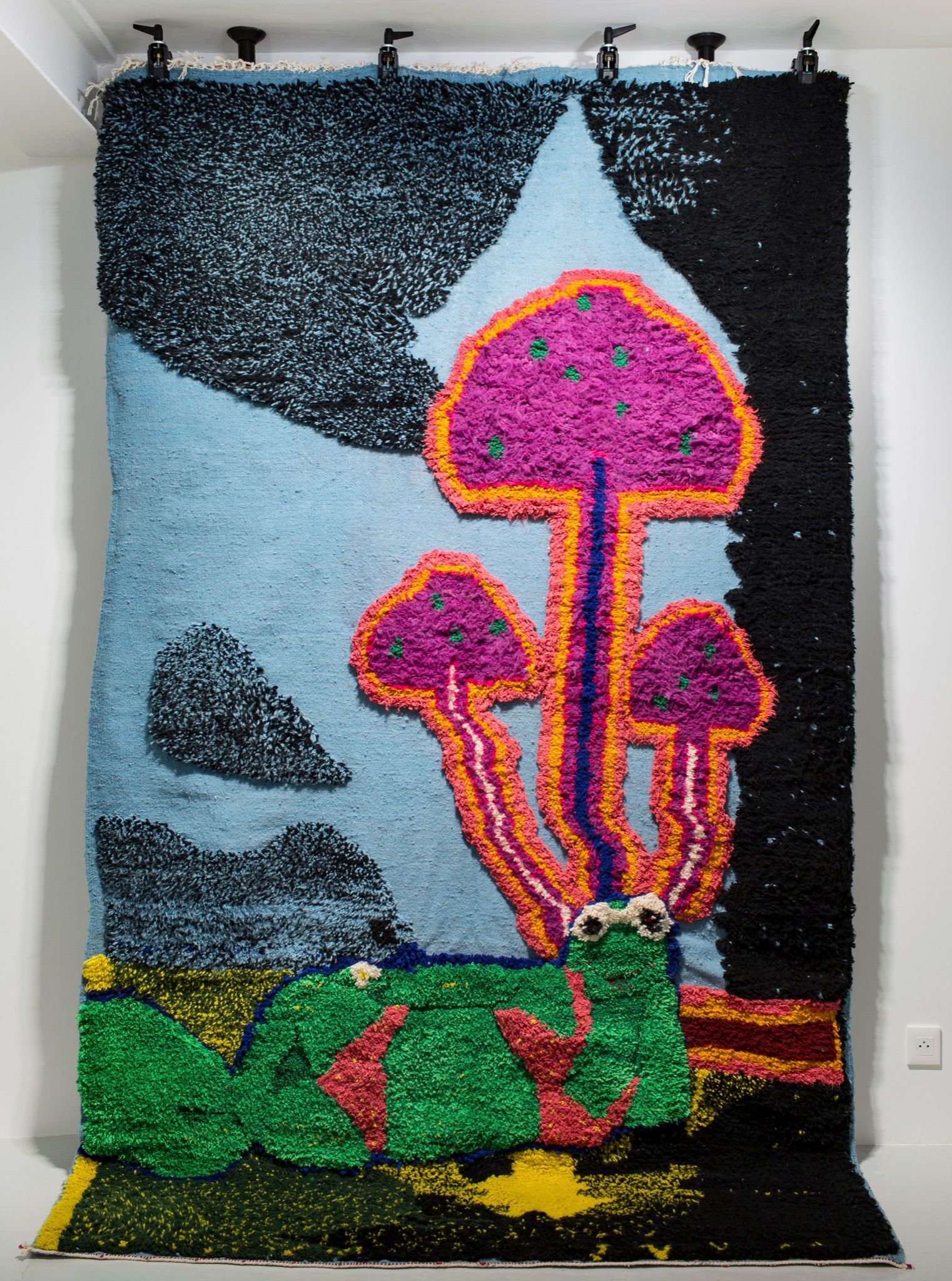

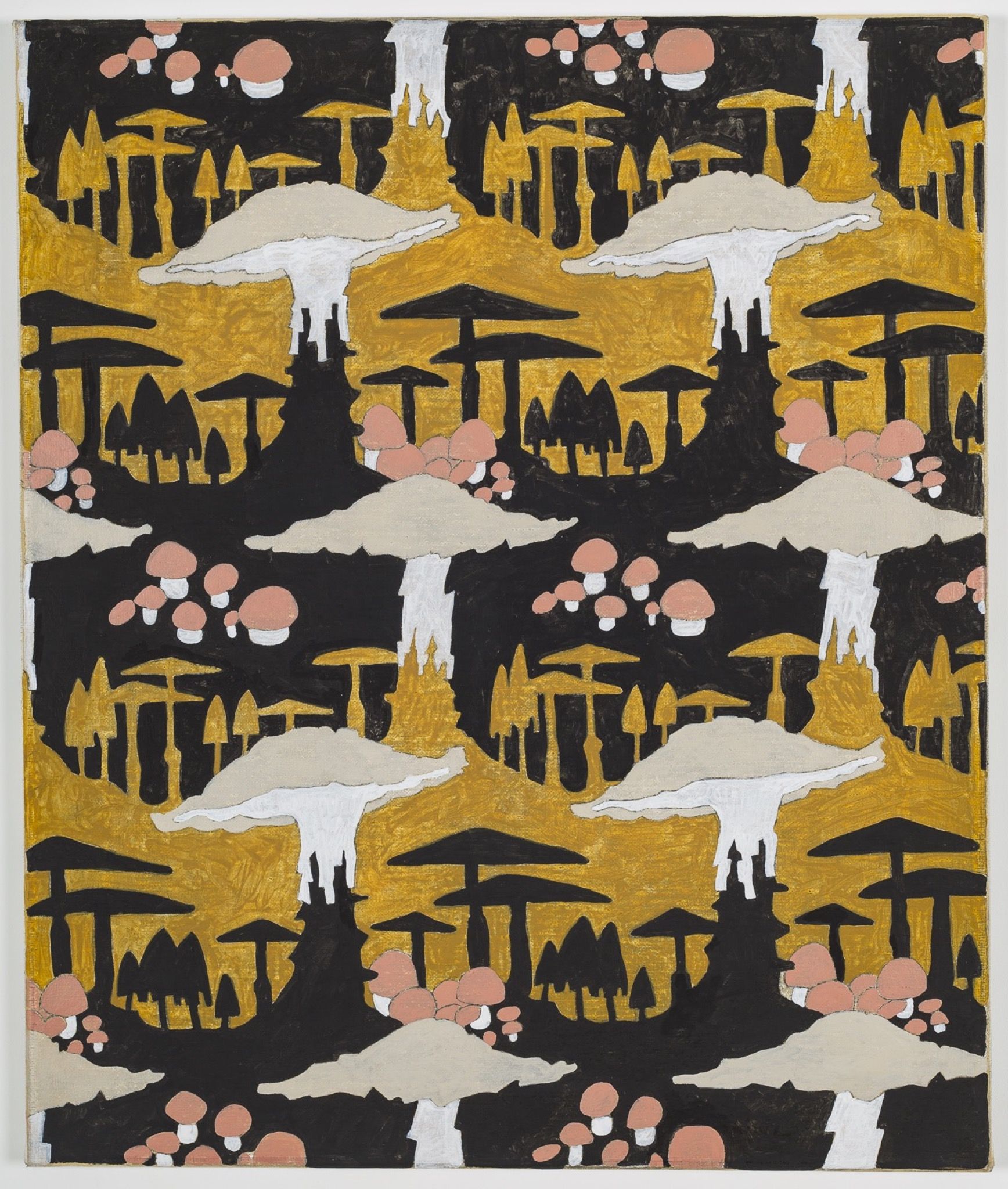

Fungi are everywhere. They exist under the earth, on top of our skin and inside our bodies. Their spores are floating around us constantly. According to the Royal Botanic Gardens Kew report on The State of Fungi (2018), the total number of fungal species on Earth is between 2.2 and 3.8 million. Ninety three percent of fungal species are currently unknown. Increasingly, fungi are also appearing in contemporary art and design. Mushrooms became prominent in paintings, drawings and collages by contemporary artists in the 1960s. Yayoi Kusama, Sigmar Polke, Paul Thek, Wallace Berman and Cy Twombly were all interested in their fleshy forms. John Cage was a lifelong mushroom obsessive and foraging expert, known in Italy more for his mushroom knowledge than his music. Today, there is a veritable explosion of mushrooms in art. Much has been written about the mushroom in terms of science and the psychedelic. Yet its position in visual history has been less closely examined. Why are artists and designers so drawn to fungi?

As climate change becomes a crisis we cannot ignore, the fragility and complexity of the natural world is becoming hugely resonant. As T.J. Demos wrote in his passionately argued book, Against the Anthropocene, we live in ‘an epoch when nature is made visible only as “natural capital”’. Demos has rightly noted, ‘Contemporary visual culture at its best can play a critical role in raising awareness of the impact, showing the environmental abuse and human costs, of fossil fuel’s everyday operations, mediating and encouraging a rebellious activist culture.’ We are living in an industrialized, digital era. Nature, by contrast, can fill some of the emotional and philosophical holes in our experience. People are looking to nature to connect to something larger than themselves. Mushrooms are nature’s computers, communicating through their hyphae like our neural networks. The late Ursula Le Guin in her 2014 lecture, Deep in Admiration, pointed out that we need ‘to get outside the mindset that sees the technofix as the answer to all problems.’ She suggests that art, poetry and visual culture can help rethink how we view nature on a grand scale. As she puts it, ‘one way to stop seeing trees, or rivers, or hills, only as “natural resources” is to class them as fellow beings – kinfolk.’

Mushrooms are far more complex friends than we imagine. Until recently, it was assumed that fungi were base plants. Scientific research and DNA testing 3 changed that, confirming that fungi were closer to animals than plants. There are two different types of mushroom: those that break down organic matter and those that carry water. The fleshy entities we call mushrooms are the fruiting bodies of the mycelium, a thread-like fungal network of hyphae that exists beneath it. Mycelium can hold up to 30,000 times its mass, at times holding soil together. It can communicate information between trees, something now referred to as the ‘Wood Wide Web’. The oldest and largest organism in the world is a fungus – the Armillaria ostoyae in the Malheur National Forest, Oregon. It is 2,385 acres in size and somewhere between 2,400 and 8,650 years old.

Humans, animals, plants and bacteria live in symbiosis with mushrooms. This multispecies entanglement is the basis of all ecosystems and an essential requirement for the possibility of life. The roots of plants, from trees to food crops, are intertwined with fungi that are fundamental in providing nutrients and water to vegetation. Without fungi, plants might never have colonized land at all. Humanity is beginning to realize how important mushrooms are for its survival. The human body contains more bacterial cells – including fungi – than human ones, and they are a vital part of our microbiome. Fungi play a pivotal role in the creation of cheese, bread, penicillin, vaccines, contraception pills and some cancer medicine. New research into mushrooms and mycelium is highlighting their ability to boost immunity, lower cholesterol, reduce risk of heart disease, reduce diesel contaminants in soil, break down PCBs, create biofuel, replace animal feed and traditional pesticides. They also taste good. The global market for edible fungi is estimated to be worth $42 billion per year.

The psychedelic nature of some mushrooms is gaining a new following. Mushrooms have become visual shorthand for referencing the ecstatic and hallucinogenic. Contemporary scientists are taking psilocybe mushrooms very seriously to help treat addiction, depression and other mental issues. New discoveries about psychoactive mushrooms are constantly being made. Mycologist Darren Springer has discovered early examples of the use of psychoactive plants and mushrooms in central Africa, used in rituals to promote radical spiritual growth, stabilize communities and family structures, as well as to resolve pathological problems. ‘Africa possesses an ancient tradition of medical plant use, though despite the continent’s floral diversity, few African psychoactive plants have been investigated,’ Springer notes.

Designers looking for new symbiotic practices for humanity’s future are by contrast looking at the mushroom for more worldly reasons – as a source of new material to replace plastic or bricks. One of the more fantastical ideas comes from the mini-collective H.Earth, which consists of the author and academic Tobias Rees, synthetic biologist Drew Endy, writer Michael Specter, artists Agnieszka Kurant and Rob Reynolds and academic Tui Shaub. Their semi- fictitious project envisages sci-fi utopian communities based around giant mycelia fermenting factories.

Even economics is taking tips from mushrooms. Some of bitcoin’s best traits are simply copied from the fungi kingdom. Cryptocurrency and blockchain consultant Brandon Quittem has made comparisons between mycelium and bitcoin. ‘Fungal networks don’t have a centralized “brain”,’ he wrote in 2018. ‘This mirrors the decentralized consensus (social contract) formed in bitcoin.’

According to Tobias Rees, the founding director of the Berggruen Institute’s Transformations of the Human program, mushrooms provide a philosophical opportunity for us to re-evaluate humanity’s place in the world. He resists looking at mushrooms as functioning in the service of humanity. The way mycelium communicate here breaks apart Descartes’ ideas around the importance and singularity of human thought. ‘On the level of chemistry, the substance that mycelium use is pretty much equivalent to the neurotransmitters in our brain,’ Rees explains. ‘You can’t say “there is a distinctive mycelium or fungal form of reason, and a non-human form of reason.”’ Mycelium communication is somewhat comparable to the human brain. The concept of time disintegrates from a fungal point of view. Fungi have a timescale that can go back thousands of years. ‘The world in which we live would not be existent without this fungal time. Fungal time shrinks the idea of human time’, Rees observes.

This exhibition looks at how mushrooms make us rethink some of the basics of our conception of the world. Art, philosophy, science, economics, industry, food, medicine are all are being rethought in the wake of mushroom discoveries. Fungi are not just crawling into plant roots. They are growing into the human imagination.

Credits

- Text: Francesca Gavin