BENOÎT JEANNET’s index of the Earth explains why we love rocks

|Thom Bettridge

In a late and particularly decadent season of MTV’s reality drama The Hills, anti-hero Spencer Pratt enters a friend’s Malibu bungalow draped in healing crystals. Things are not going well. A drama bomb has exploded at dinner the night prior, and as Pratt frantically recounts the tale, he clutches a chunk of rose quartz to his third eye. “I don’t think the crystals are working,” his friend injects, “You’re hyperventilating. You’re red-faced.” Pratt then looks at him, wild-eyed. “I know they’re not working,” he says, “That’s why there’s hundreds on me right now.”

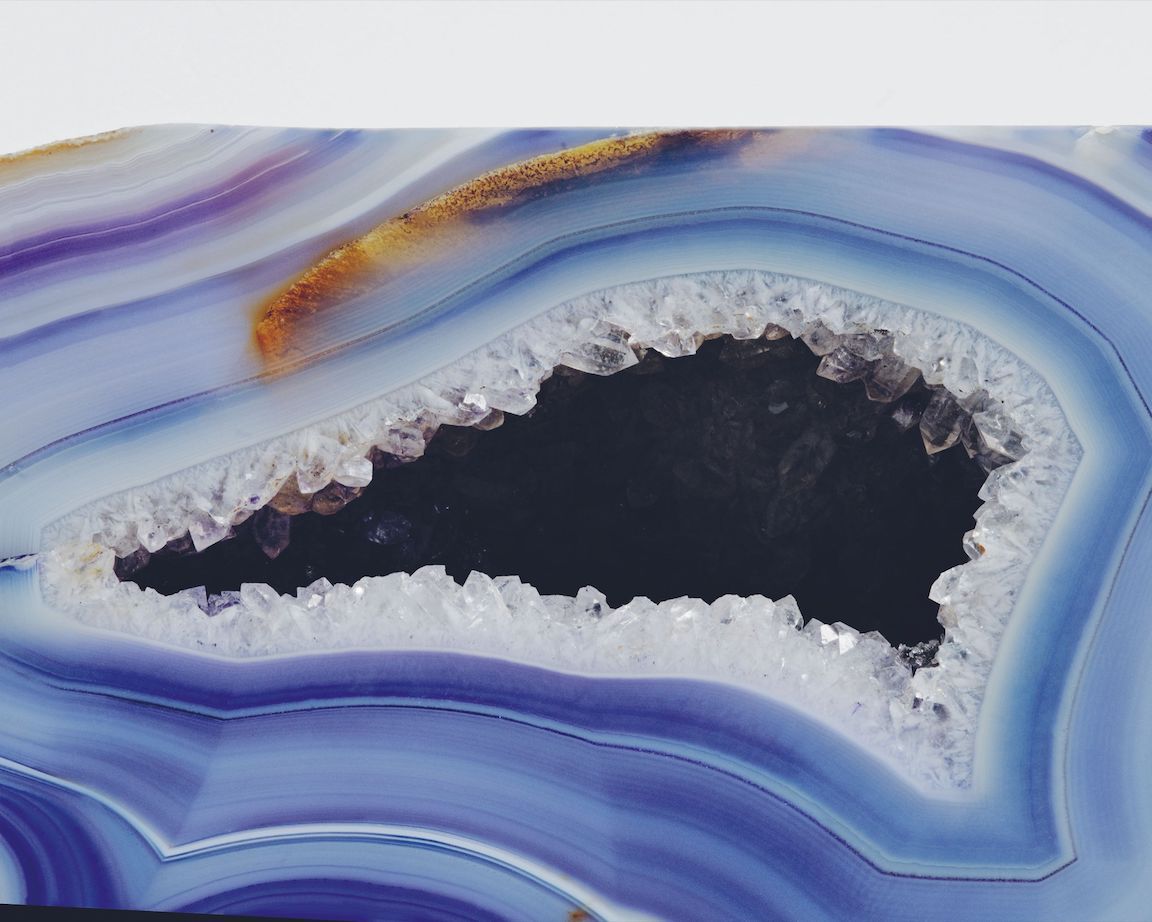

Despite its hard surface, Geology is a theater of the absurd. The timeline on which rocks operate runs so far into the millions that to contemplate their nature is to inhale a deep breath of existential laughing gas — a state in which writing a novel, or using amethyst to ward off bad energy seem equally worthwhile. This giddy feeling of immenseness lingers in the background of artist Benoît Jeannet’s seemingly austere A Geological Index of the Landscape. Even the photobook’s title, which claims with a tongue in its cheek to catalogue the entirety of the Earth’s material in 235 images, casts itself full-on into the irony of the impossibly large.

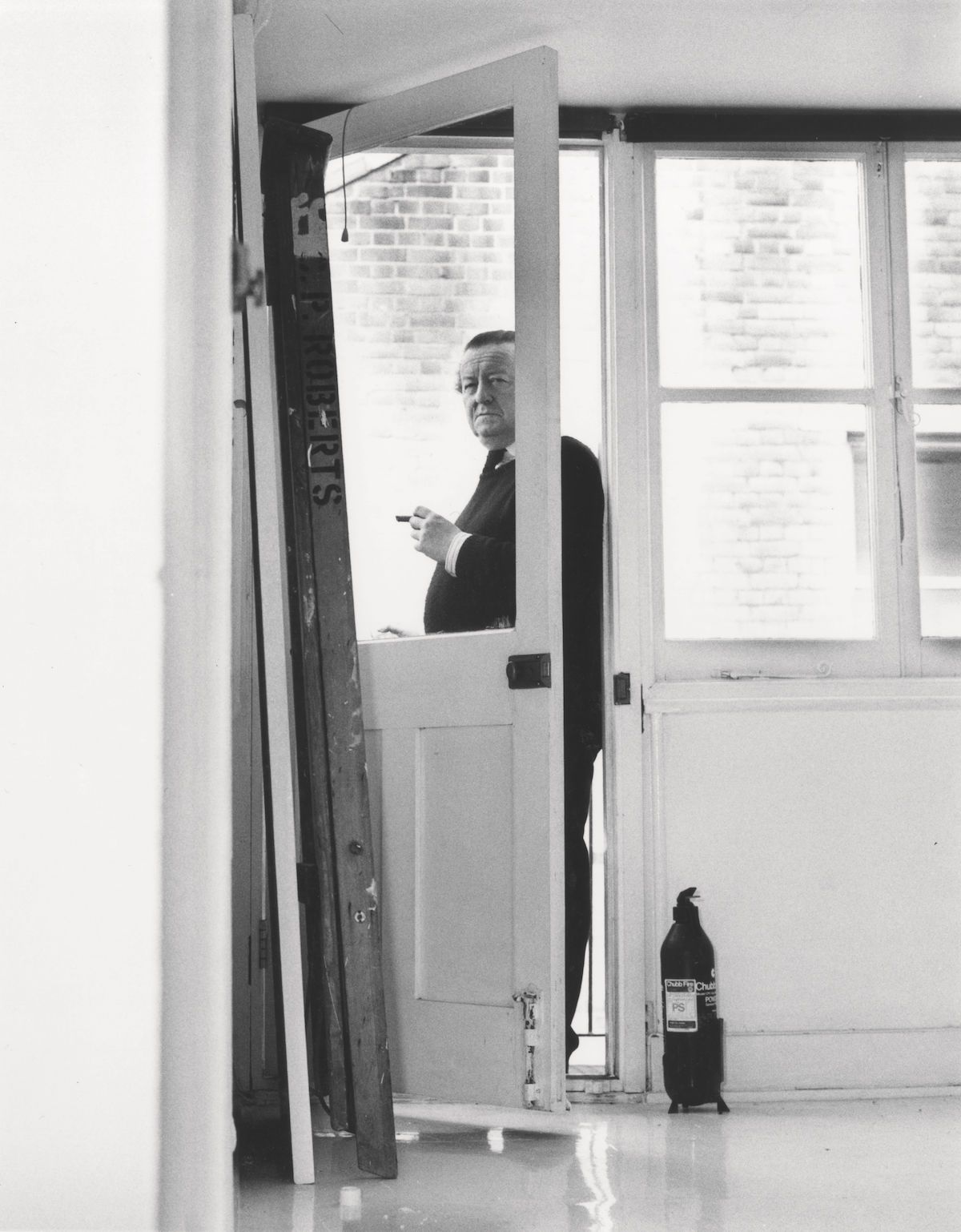

Organized as a series of deadpan, Dusseldorf-y, large-format photographs, Jeannet’s volume is a winding conversation between microcosms and macrocosms. Streaks of azure blue in its tightly-photographed crystals find their twins in the glowing tide pools surrounding city-sized rock formations. Scale, color, age, texture — when thinking in a geological mode, the degrees of magnitude that define these categories seem increasingly arbitrary. Slowly, glacially, we discover that “landscape” in the scope of Jeannet’s book is not something one finds out in the world. Rather it is a human invention, a framing device used to make the world small enough for humans to understand it.

A Geological Index of the Landscape is published by Morel Books (London, 2017).

Credits

- Text: Thom Bettridge

- Photography: Benoît Jeannet