“Slowed & Throwed”: Exhibiting DJ SCREW

|Jeffrey Martín

Debuted in March 2020 to staggering crowds, “Slowed and Throwed: Records of the City through Mutated Lenses” – a multi-disciplinary exhibition of archival materials and contemporary artistic responses to the life, work, and impact of the late DJ SCREW – reopens at the Contemporary Arts Museum Houston this month following pandemic-related closures. In this two-part digital feature, interviews with exhibition organizers, advisors, and participating artists expand on the DJ SCREW story inspired by the show and published in 032c Issue #38 (Winter 202/2021), where quotes from these conversations accompany imagery and essays exploring the legacy of the Houston musical legend. To read additional texts available only in print, click here.

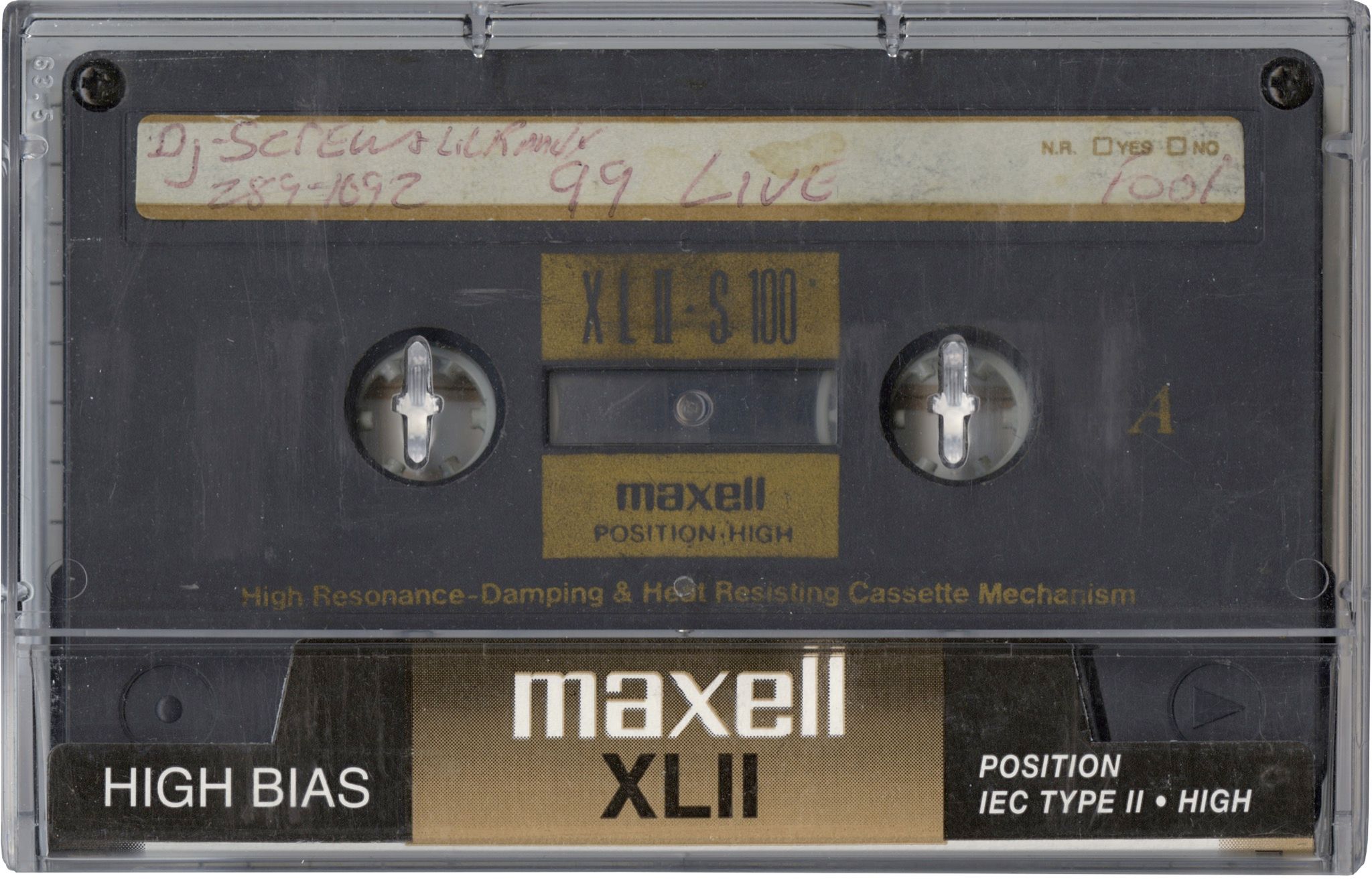

It is impossible to discuss Southern hip-hop and community without first mentioning DJ Screw, whose creation of the “chopped and screwed” method had resounding impacts on the cultural identity of Houston, and on global hip-hop production. Non-Houstonian consumers of the commodity that is contemporary hip-hop may have heard of the “mumble” and “SLAB” cultures affiliated with chopped and screwed, and run with the shallow picture of what many say caused the creation of the famously “slowed down” culture: purple drank. As a popular product sold and distributed on a mass scale, lean has become a scapegoat for hip-hop audiences who fail to understand the history that underlies its avid consumption – a backdrop of social oppression, which likely had greater formal impact on Screw’s mixtapes than any codeine-laced beverage. “The way he took the culture of selling tapes – it was like dope, to the effect where cops raided the house because they thought they were selling drugs, because it was such a long line outside,” says artist Robert Hodge, who grew up with members of the Screwed Up Click. “The entrepreneurship in it was really impressive.”

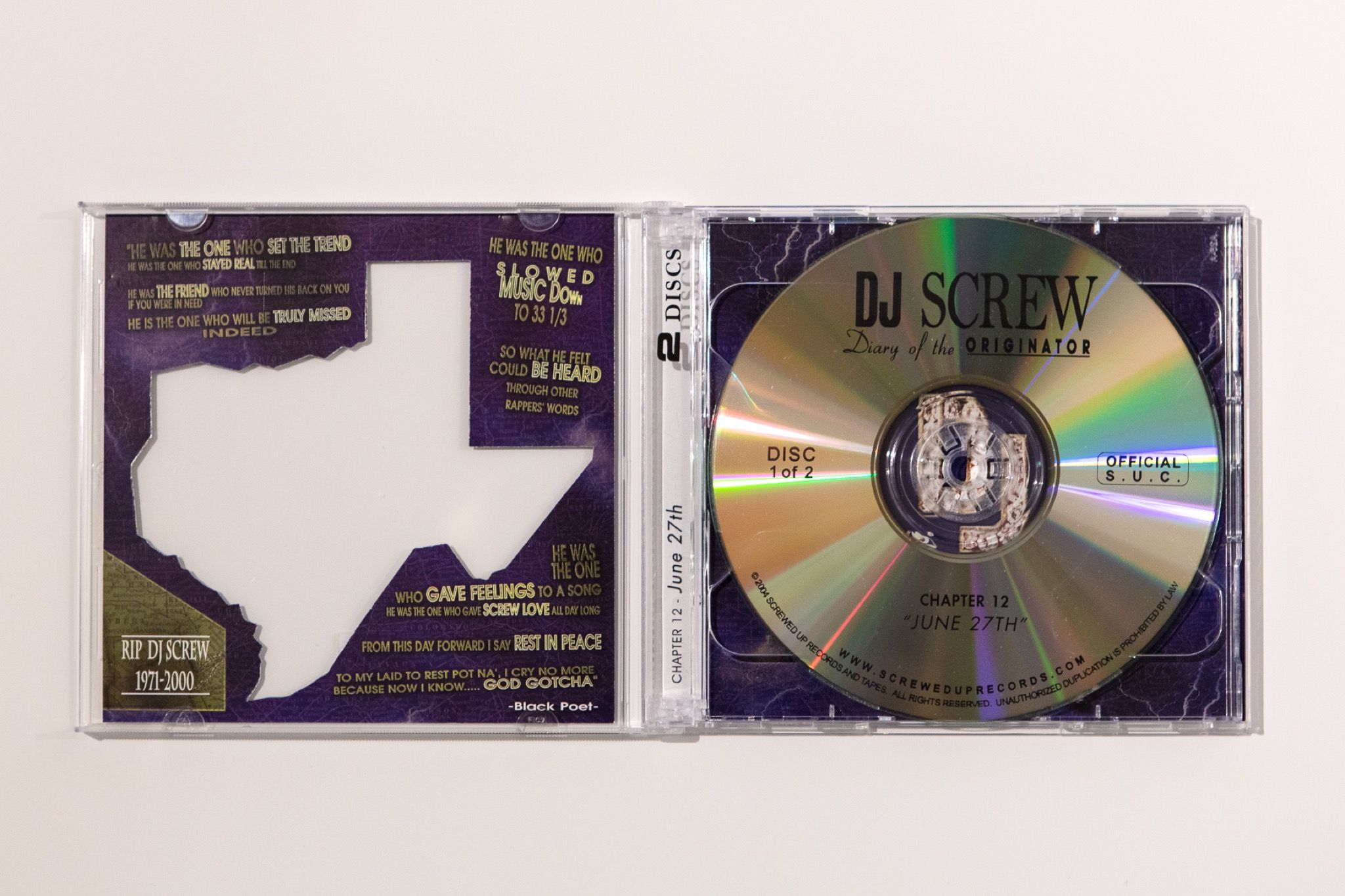

DJ Screw passed more than 20 years ago, locally canonized and regionally famous, 17 years into his DJing career, at only 29 years old. He left behind the Screwed Up Click (SUC) and a shop called Screwed Up Records and Tapes, both of which are still around, albeit in modified form. When his body was found in November 2000, mad cow disease was terrifying Europe. George W. Bush Jr. had won his election against Al Gore – a narrow and controversial victory against the “environmental” candidate despite mounting concerns around climate change and, that same month, the first Global Warming Conference in The Hague. The Clintons were on the way out of the White House but nonetheless on the rise to coupled political power, with Bill being the first president to visit Vietnam since the war and Hilary being elected to US senate. There is something fair and foul in the resonant air we find ourselves in February 2021 as COVID and her mutated sisters have continued to shed a light on the toxicity of agriculture and trade, and the public health crisis that is racism. People seem, at least on the surface, to be rethinking the power and structures of the institutions we have always lived with – the same ones traditionally tasked with evaluating and preserving our cultural histories.

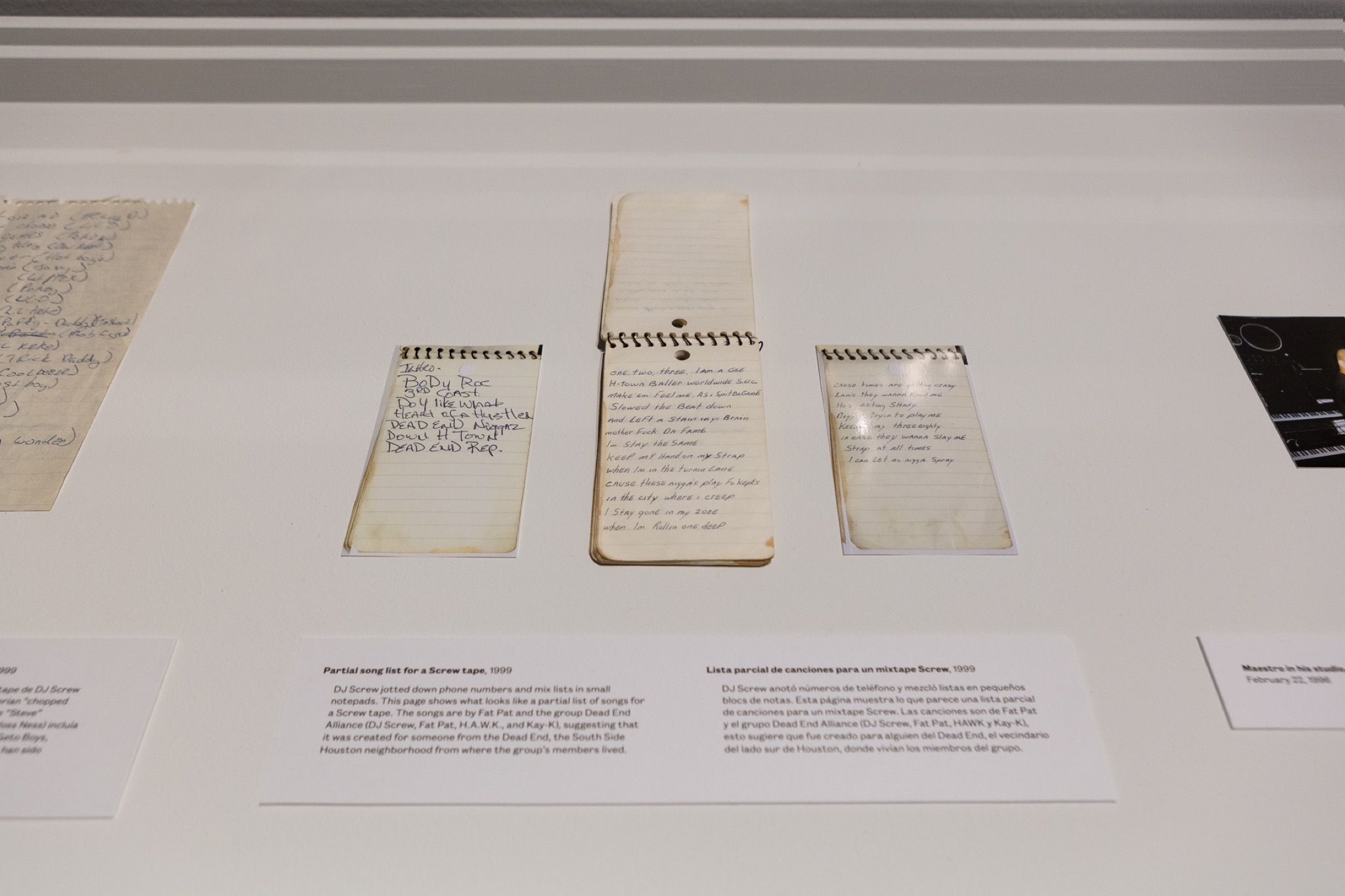

Hip-hop has long functioned as a cultural archive for Black stories not often told outside the communities who preserve them. Screw’s tapes were highly personalized playlists of distorted samples and remixes, cut to respond to the mood or surroundings of a fan, a neighborhood, a news item. They tell stories of excitement and opportunity, of economic and political hardship, of the systemic disadvantages of living in a world where your power, as a Black person, is concealed from you. How can institutions conserve and display Black archives such as Screw’s, when institutions were built by the same racist and capitalist structures that threaten to wash Black stories away?

“DJ Screw’s way of music making and collectivity was a form of critical practice,” says Hodge. “It was grassroots, democratic, and regionally viral. As we know, the music industry shut down that method of working, and it is no longer lucrative or legal for musicians. Mixtape production was one way in which street ingenuity outthought and outmaneuvered the music industry.” Hodge is one of 19 artists featured in “Slowed and Throwed,” an exhibition co-initiated by Contemporary Arts Museum Houston (CAMH), the University of Houston Libraries, and DJ Screw’s Chop Shop. The interdisciplinary and archival show explores how Screw’s chopped and screwed technique is embodied in contemporary artistic practices, and how his unique ability to create space for community and collaboration can be channeled through an institution. “Because of who made this music, where it came from, and its initial resistance to corporate control, Screw music and its practitioners were overlooked and undervalued,” says Hodge, who sees “Slowed and Throwed” as one step in finally giving “the proper amount of attention and respect to many aspects of our local culture.”

To tell Screw’s story in the words of the people who knew and influenced him, CAMH curator Patricia Restrepo also tapped SUC member, ESG and Screwed Up Records & Tapes owner Big Bubb to be the exhibition’s guest curators, alongside independent hip hop educator Rocky Rocket, and Julie Grob, curator of the Houston Hip Hop Research Collection at the University of Houston, as research advisors. When I spoke to Restrepo, ESG, and Rocky about the project, we delved into knowledge accessibility, the deep waters of southern hip hop, and how to sustain the Black archive – in an actual flood, and in the storm of violence and inequity that made and slayed DJ Screw.

DJ Screw made everybody feel like a star, even if they were just coming up in their music career, or just trying to say some things to represent the neighborhood. Why was community so important then, and how were y’all able to forge it?

ESG: The community is always important bro, you know what I’m saying? Screw recognized everybody was from different communities. You have to think about how a Screw tape was made: it was just like a playlist of today, so that means a Screw tape may consist of eight different individuals and eight different songs that they all like. It was not one person all the time picking those playlists. And as time goes on, the people listening to those Screw tapes may be from a Latino community. Or a tape may have a song from people who are from a Caucasian community – you may have old school Elton John, Bon Jovi, chopped and screwed with an Ice Cube song or this and that. So therefore the genre of music on the Screw tape is going to be a variety so as time goes on and on, the listeners will listen to the music in those tapes. You want your community to be a great place to live and a vibrant area for the youth and all that. The way the economy is right now, it’s so hard. If you look at the Third Ward community in Houston you have $200K to $400K high rises, $1M Homes – right next to a property that’s maybe valued at $50K to $90K. But that’s what’s going on in the world and what comes up for me when you mention the community.

Rocky: I saw a lot of people were able to come together across the communities within this exhibition. Actually being and seeing so many diverse individuals in the room celebrating DJ Screw’s legacy was a pivotal moment for me. The show merged our city – for some that was the first time they had stepped into a museum. It was amazing to see.

ESG: This exhibit was for everybody, and it was all a peaceful thing. You have so many things going on around the world nowadays, with police and everything that they got going on, that’s trying to separate the community. It’s just so crazy what I’m watching, what’s going on from Wisconsin to Portland right now. This will be great to try to bring us back together as one, you feel me?

Yeah very much so – even just in terms of George Floyd having been involved with the SUC. After November 2000, when Screw passed away, his death was memorialized into something that was so much bigger than him.

ESG: Man to think that he’s been gone 20 years, right? It wasn’t as big then, but by the time he passed it was big regionally, big everywhere else nationally – but it wasn’t worldwide. Now it’s starting to grow worldwide – look, that’s crazy. 20 years gone the Screw shop is still vibing, and now it’s people that come in from West Texas. On my album South Side Still Holding, I actually have a guy from Germany doing a verse. There’s a worldwide remix. I have somebody from Brazil on the song, you feel what I’m saying? This is crazy.

There was never no hate on the Screw music, there’s never been that, for certain. It was all about, “just slow down the music, man.” It comes from the culture, man, what we was doing back then, sipping and smoking, just riding, let’s just slow down the music. That’s as close to religious as anything.

Rocky: And people who don’t like Screw music, like E just said, aren’t attached to the culture anyway. If you’re not a part of it we ain’t worried about you.

“I found that flattening of his skill – not acknowledging that he was an avant-garde artist who improvised all of these tracks – to be a super racist rendering of his talent. Yes, lean existed as part of the culture, but he was a creative force that shouldn’t be seen through some limited perspective because of that.”

How does racism play within the scope of Screw culture and lean culture? A lot of the artists in the chopped and screwed scene had experienced racism and medical racism. How does Screw culture help us transcend it?

Patricia Restrepo: From an art historical approach as I was delving in and reading every single thing I could get my hands on about Screw. The centering narrative was around lean as the causation for the innovation of chopped & screwed, the sole driver. From my perspective, I find that highly problematic in that, of course, lean was part of the culture, but through my lens I saw it as a racist flattening of a really complex history and of an avant-garde skill. So many white artists, and other artists throughout history, have had different types of substance use. Yet when we read about those important avant-garde artists, their work is not solely linked to that. It might not even be included in their bio, any type of causality tied to that drug. So I found that flattening of his skill – not acknowledging that he was an avant-garde artist who improvised all of these tracks – to be a super racist rendering of his talent. Yes, lean existed as part of the culture, but he was a creative force that shouldn’t be seen through some limited perspective because of that. The cops tried to raid Screw’s house several times, because they were like, “how can this Black, poor person be having so many people at his house at all times of the day and be making all this money?” They didn’t want to see that there was this talent who had created such an uncontrollable demand that lead to his success – despite all of these limitations that were placed on him.

E, you were touching on religion. This music – it’s a form of processing.

ESG: If you go to Screw House, you don’t want to hear the same thing that’s on Top 40, right? At Screw House I get to pick a song that speaks of equality or talks about racism or police brutality. For example, you’re a person who feels oppressed and is going through that in society and in your community, and you get to make a Screw tape as a person who goes through this and pick a record that resonates with you, that resonates with what’s going in your environment. Now a copy is made of that Screw tape you made and passed out to so many different people – people who may then buy a full album. So you get to get your name out there through your song, and it almost becomes a freedom of speech mixtape, you know what I’m saying? You get to go in there, even if you’re a person who can’t really rap – you may just want your voice to be heard in your community, and that’s something you can do on a Screw tape. Now hundreds of thousands of people get to hear your neighborhood views, or your so called political views, you feel what I’m saying?

Rocky: Hip-hop is the newspaper. Actually, mixtapes are the newspaper of the streets. When you were first making the statement about mixing social justice with DJ Screw, it seemed like a little bit of a stretch. But the reality is that these people came from different neighborhoods and with mixtapes they’re able to talk about things in their neighborhood that aren’t just drugs. It was talking about people who were in their neighborhood, police brutality, cops in general, the injustices of the judicial system, people being locked up. I’ve heard on a couple of Screw tapes, individuals shouting E out when he was locked up – putting their voice and whatever they felt at the time out there without a filter.

“Slowed and Throwed” is curated by Patricia Restrepo, Exhibitions Manager and Assistant Curator, Contemporary Arts Museum Houston, with guest curators Big Bubb, Owner of Screwed Up Records & Tapes, and ESG, rapper and member of the Screwed Up Click. The exhibition is also made possible through the assistance of Research Advisors Julie Grob, Coordinator for Instruction and Curator of Houston Hip Hop Research Collection at the University of Houston Libraries, and Rocky Rockett, independent hip hop educator. The artists featured are B. Anele, Rabéa Ballin, Tay Butler, Jimmy Castillo, Jamal Cyrus, Ben DeSoto, DJ Screw, Robert Hodge, Shana Hoehn, Tomashi Jackson, Ann Johnson, Devin Kenny, Liss LaFleur, El Franco Lee II, Karen Navarro, Kristin Massa, Ayanna Jolivet Mccloud, Sondra Perry, and Charisse Pearlina Weston.

Credits

- Text: Jeffrey Martín