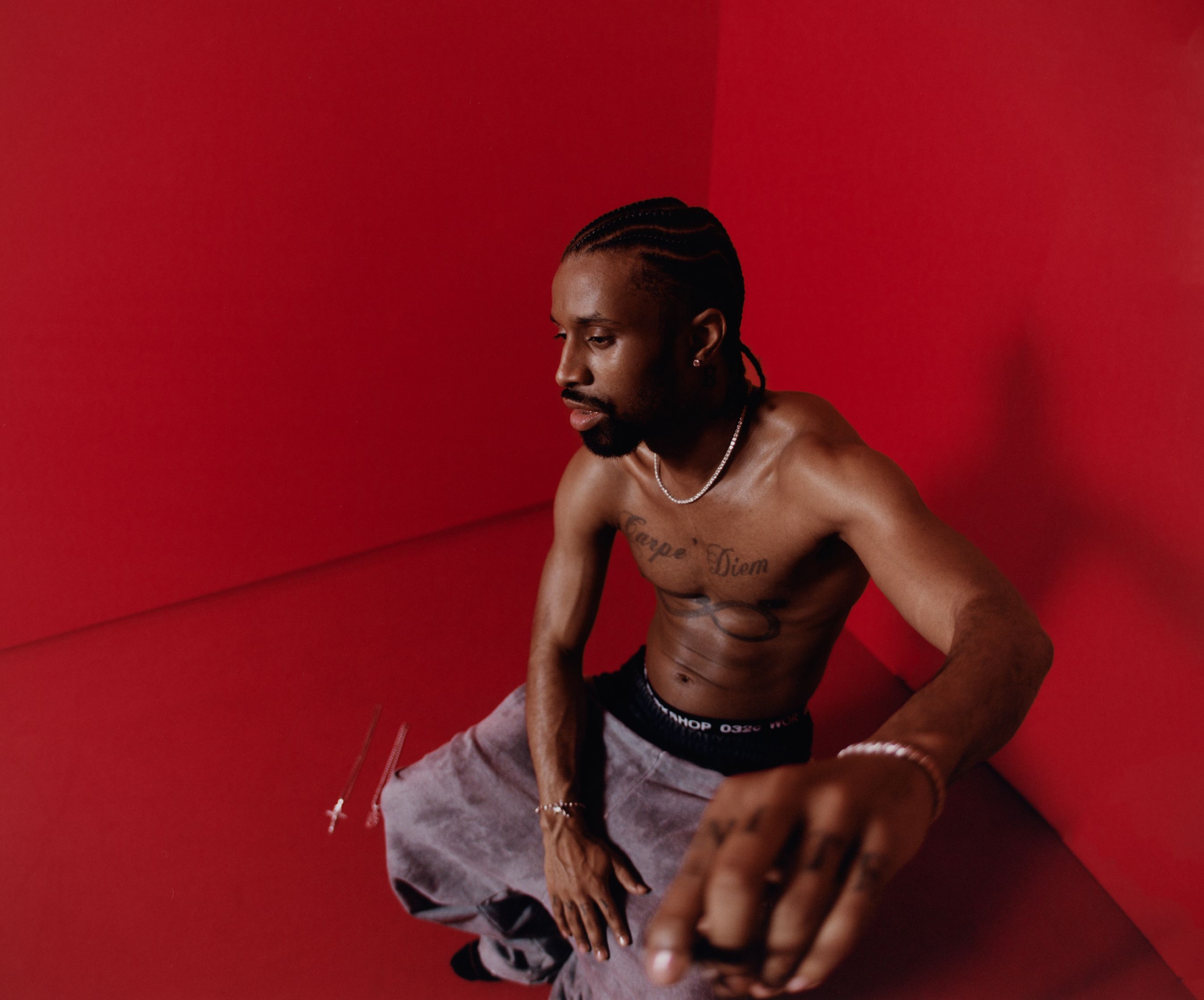

Aus Taylor: If I Died Tomorrow, I Would Be Satisfied

|CLAIRE KORON ELAT

“Even though I haven’t really made anything that amazing, if I died tomorrow, I would be satisfied,” says director and visual artist Aus Taylor.

underwear 032c WORKSHOP BOXERS, pants “GLOW” STAINED SWEATPANTS

Having collaborated with the likes of Ye, Steve Lacy, Paris Texas, and others on their music videos and live performances, the Baltimore-born Taylor never traditionally studied film. Yet his direction—even for short form videos—is suffused with complex narrative and visuals that transcend to video art. And although he doesn’t explicitly describe his work as political, there are often subliminal statements to be found about the state of America, race, or social marginalization. His most recent video artwork, which was directed in collaboration with Ye and features sex workers and gang members in LA, looks at class division and societal issues from an artistic vantage point, aesthetically transforming forms of struggle without ever simply surrendering to beauty.

In the first interview he has ever given, Taylor discusses artwork that can’t be understood, having a social agenda, and why you need to be uncomfortable to produce.

CLAIRE KORON ELAT: One of the films that made you interested in direction and photography is Mathieu Kassovitz’s La Haine (1995). There’s one line in the film that I found particularly interesting: “It’s about a society on its way down, and as it falls, it keeps telling itself, ‘so far, so good, so far, so good.’ It’s not how you fall that matters, it’s how you land.”

AUS TAYLOR: It was the first movie I saw as a young adult that was art house. Before that, I had only seen blockbusters, such as Saving Private Ryan—which is incredible and one of my favorite movies. I think I was in tenth grade when I saw La Haine. They were young characters, so I felt like I could relate to it. I had never seen a black and white movie that didn’t feel super old, like Chaplin or something. And Mathieu Kassovitz was a young director; he was 27 when he directed it. I respect the bravery he had to just put something out into the world. That movie was just visual poetry. It was the first movie that made me look at movies from an artistic perspective.

The quote feels a bit like the story of my life. It’s not about what I went through, it’s about the fact that I’m here. I landed on my two feet and I’m still here. I’ve shot probably over 300 or 400 music videos in my career and people know me for two or three things.

CKE: Do you find it problematic that some people only know you for two or three projects?

AT: It bothers me, but it also doesn’t. The only time it bothers me is when people think that I came out of nowhere or think I’m a nepo baby or something. But I have been doing this for 15 years, right when I was fresh out of high school.

It bothers me when people see the work I’ve done with Ye or with certain people, and that’s where they start my journey from. In a way, that was a new beginning for me. I worked my whole life to be prepared for that moment. I also don’t do a lot of press, so it’s also my fault to some extent. I don't think people know that much about me, so I can't really fault people in what they see on the internet. But I would hope that they do their research.

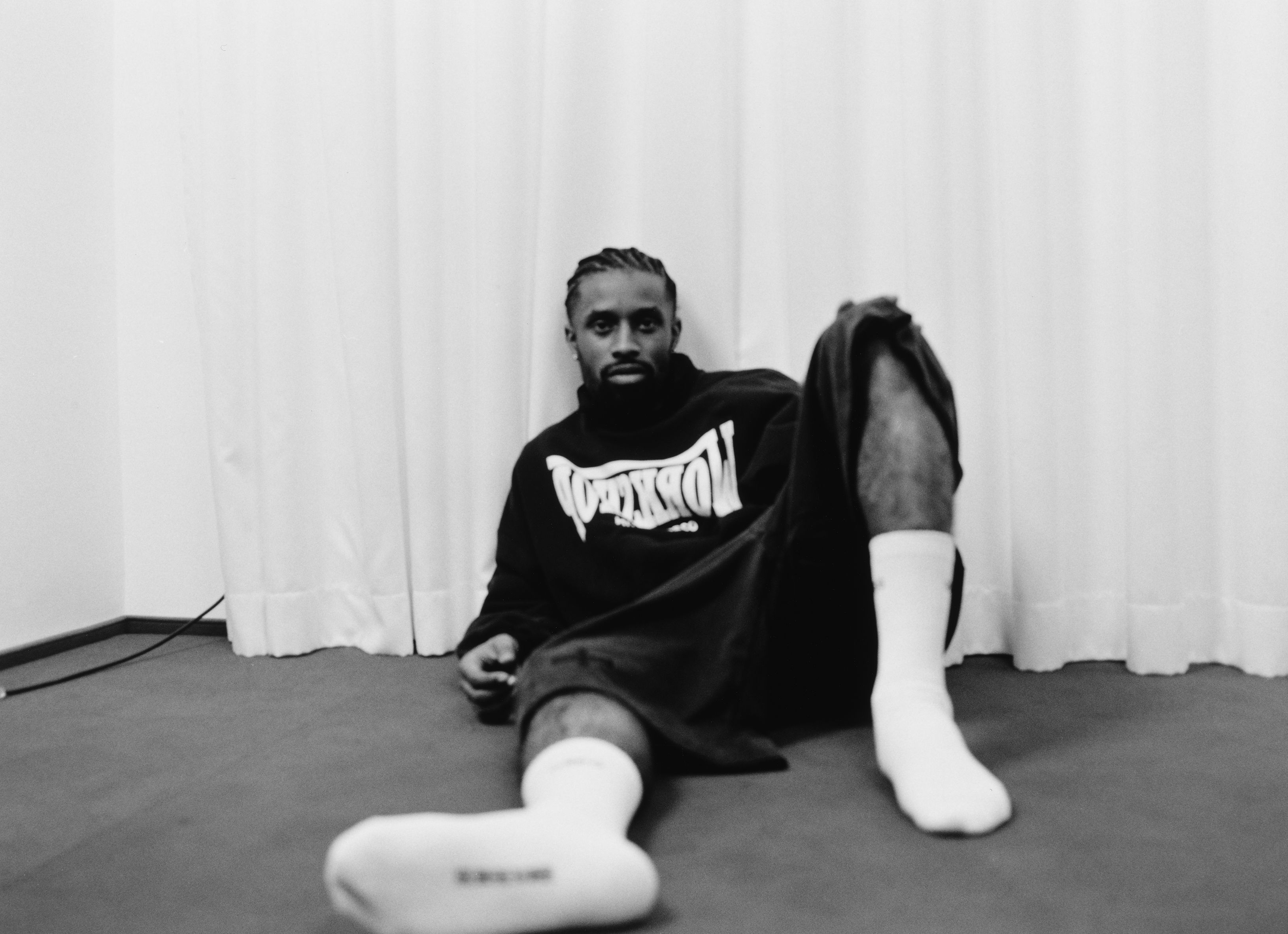

top “VICTOR” BUBBLE CREWNECK, underwear 032c WORKSHOP BOXERS, pants “GLOW” STAINED SWEATPANTS, socks “REMOVE BEFORE SEX” SOCKS

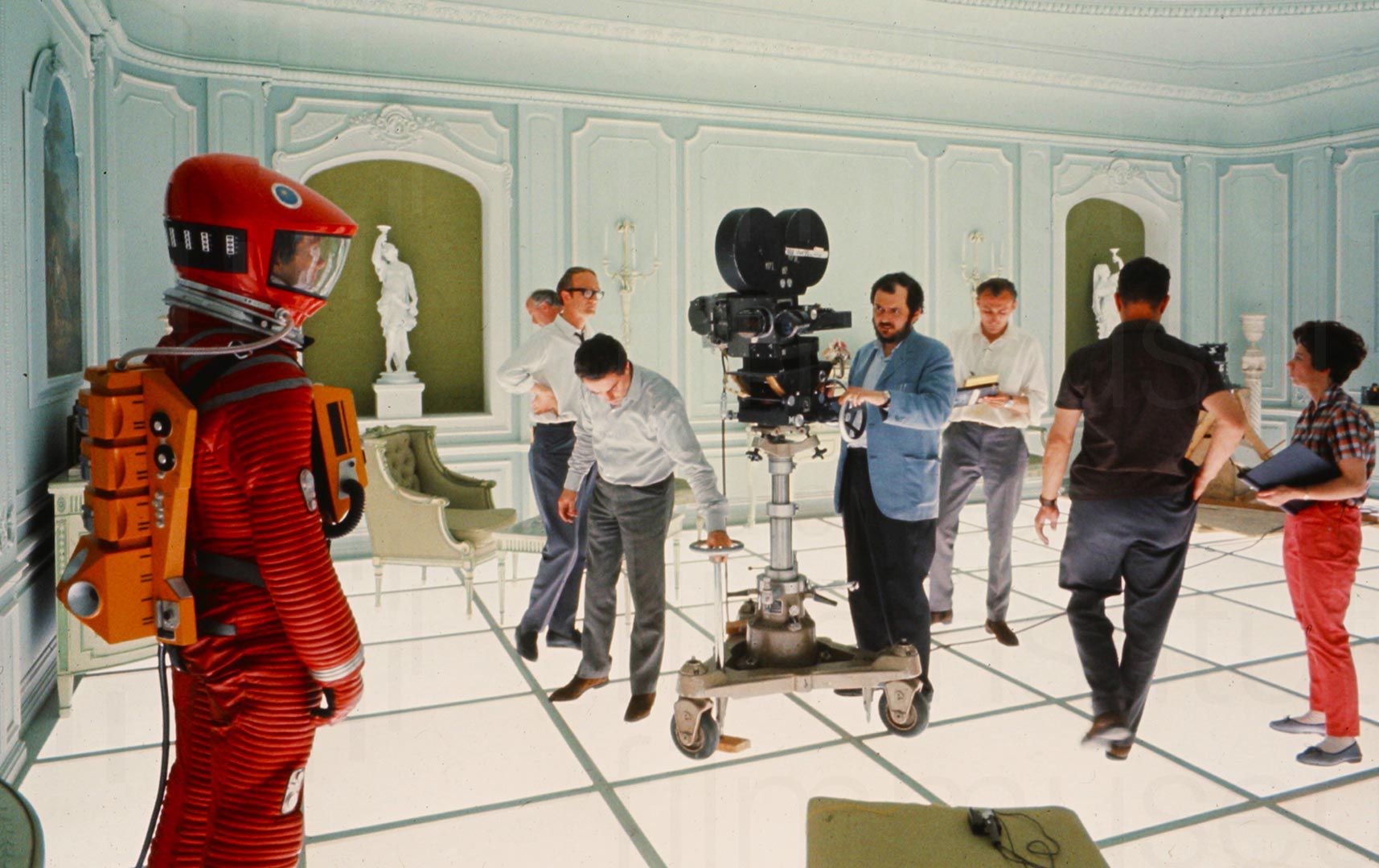

CKE: There are also many artists or directors, such as Stanley Kubrick, who specifically didn’t want to talk about their work publicly because the work should just speak for itself.

AT: I can certainly relate to that. I don’t want to ever explain my work. Obviously, my work has a lot of depth and nuance, but I agree—you like it, cool. You don’t like it, cool. Understand it, cool. Don’t understand it, cool. I'm not trying to be understood. I’m not even trying to say anything. I’m trying to do something, I’m trying to get an idea off. Sometimes, you can explain an idea that’s amazing, and it will sound stupid because you explained it. I don’t think art is meant to be explained. It’s meant to be felt and interpreted however you want.

CKE: I think what drives a lot of people who do creative work is their interest in things they can’t understand, that are intangible on an intellectual and perhaps also visual level. Would you say that you always understand your own work?

AT: I have an understanding of my taste, and I have an understanding of what I stand for as an artist. I try to not box myself in. I don’t think when I’m making something I’m like, “I really hope people understand this.” I more so hope they feel something rather than understand it—whether it’s a good feeling or a bad feeling. I think it’s all the same in a way.

CKE: La Haine also deals with police violence and the social defects of a city’s lesser privileged areas. You grew up in Baltimore. How did this affect you, and do you feel like it informs your work today?

AT: I’m from Northeast Baltimore. I basically lived there my whole life, until I was 22 years old. One thing about being from Baltimore is that it’s such a tough city and you deal with so much on the home front that you kind of just know when somebody’s from Baltimore because they have this fearlessness. Everything else is, I’m not going to say a walk in the park, but I have a hard shell around me. It also gave me this fire that I bring into my work and into the business and industry of creating.

Also, I had to leave my home to even get to where I’m at. There’s a very low ceiling where I’m from, so you have to really break from that to become what you want to become. I always say that I’m glad I’m from there; it gave me a swagger that I carry throughout the world.

CKE: How can you tell when someone is from Baltimore?

AT: Besides the accent, it’s just the way somebody carries themself. Even the fakest person in Baltimore is realer than most people.

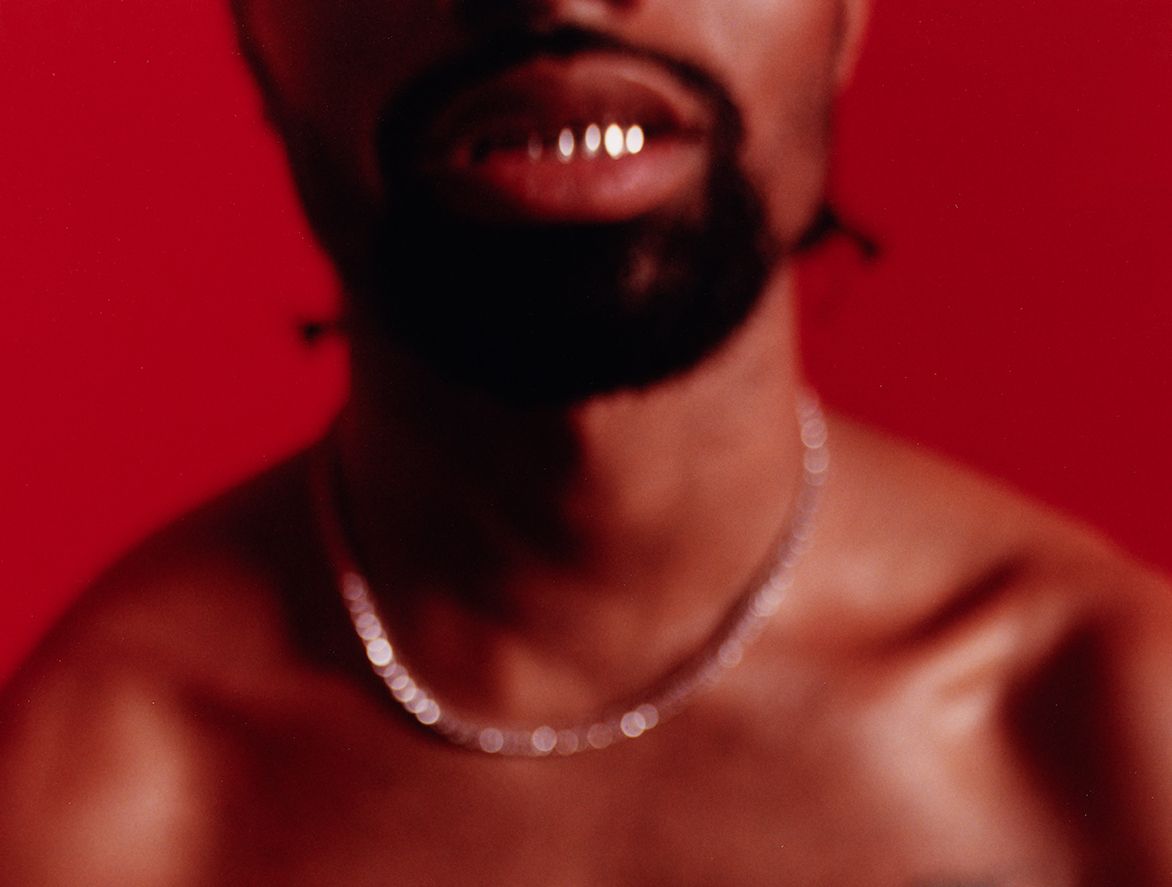

sunglasses MYKITA | 032c ALPINE, top “VICTOR” BUBBLE CREWNECK

CKE: When you produce work do you have a social agenda?

AT: It varies with each project. I’ve made very political work about police violence, but the social and political stance I have is to have your own stance—to just have your own perspective and not play with the box that they put us in. I don’t go out of my way to be political. But I feel like it’s in me as a human to go against the status quo.

For instance, with the project I did in collaboration with Paris Texas, “Bullet Man,” it’s entertaining, dark humor, but against the backdrop of Middle America. It touches on issues such as gun violence. However, even with that project, we purposely never said what it’s about. It’s one thing to be provocative, and one thing to be political. One of the most political and rebellious things you could do is allow other people to have their own opinion. Art is about reflection, not indoctrination. I want to raise questions instead of giving explicit answers.

CKE: Thinking about the political climate in the US but also worldwide, to what extent can you “allow” certain opinions and where do you need to draw a line; to what extent can these political opinions be veiled as artistic freedom?

AT: At the end of the day, no opinions matter, but all opinions make a difference. Everyone has their stance. I can’t tell somebody what to believe because the only reason I believe what I believe is because of how I was raised. So, it’s not like I really chose. If you want to make a political statement, you just have to be prepared for other people to also have their opinion.

CKE: And at 22 you moved to Paris. What did you do there?

AT: It was funny because I really wasn’t doing shit [laughs]. I moved there with all of my best friends and some of my closest collaborators and childhood friends. People would be like, “What are you guys doing out here?” And we would just be like, “We’re just existing, we’re just living and skating, we’re just…nothing.” Somedays, I would just sit in my house like it was my house in America.

The reason why we went to Paris was La Haine. My dad actually took me on my first plane ride to Paris. He was living in France at the time, and it was just the first place I ever went to, so I was like, I have to live here, because it was the only place I knew outside Baltimore, New York, and Philly. That period changed me a lot. It showed me that the world is a big place, and it taught me that you can do whatever you put your mind to.

top PROTOTYPES, jacket 032c

CKE: Now, you’re based in the US. How would you compare creative production there versus in Europe?

AT: I look at America as a video game. I know that it’s just a game, but I still want to play it. I’m always conflicted with America because I have my political beliefs about it, but I’m also from there and my whole family is there. My mother’s side of my family is indigenous, so I’m conflicted with living in America and not living in America.

As far as creative production goes, the way you can create in places such as LA is at a different speed and quality level. Obviously, I’m not inspired by LA. I’m more inspired by European cities and other places in the world. That’s why there doesn’t have to be a reason when I come to Europe. I come here to absorb the energy and bring it back to produce. And, of course, LA still has culture, but that’s Black American culture.

CKE: Aaron Sorkin said that he thinks of LA as a mediated town that you can only view through the fictive framework of its mythologizers, so it’s not actually real—like you were saying, it’s a video game. Do you think that creating under these almost fictive circumstances enables creative work more freedom than being in a comfortable place?

AT: I don’t really seek comfort. I’m not trying push the whole tormented artist narrative, but one of the reasons I can live anywhere in the world is because I feel like I really exist in my mind.

If I were to do an exhibition though, I would want to do it in Europe, just because of the contrast. I think it’s the balance. In certain places such as Sicily, I’m so comfortable that I have no ideas. When I’m in the hood in Baltimore, I see more. Maybe that’s my trauma, but if I’m on a vacation, I’m not really inspired.

You need to experience life and go through conflict and turmoil, but you also need clear spaces to sort through your thoughts, like me being in Berlin right now. It gives me space to download everything that I have been going through. It’s a balance of having comfort and discomfort as an artist.

CKE: So, social struggle inspires you?

AT: No, I would say everything inspires me, not just one particular thing. I’m inspired by all types of shit—memes, a conversation I had at a coffee shop, things from my childhood, things I’ve seen growing up in Baltimore, things I’ve seen in the world. Everything can be inspirational, good and bad things.

full look 032c

CKE: You’ve collaborated with a number of different artists. What is the dynamic between you and the collaborator? I was thinking about this because it used to say in your Instagram bio that you don’t take commissions.

AT: The no commissions thing puts up a wall for me of protection: “Don’t hit me unless you’re really trying to make some shit.” And it’s to let people know that I’m not motivated by money.

I look at a commission like, “I have this amount of money, and I want you to do this.” It’s more of a service, which I think is important too. I love to serve artists and their careers, their ideas, and to help get them to a level. But I love artists with whom I have a mutual admiration. There are big artists that have contacted me and who are fans, but I’m not necessarily a big fan of them, so there’s a disconnect. I’d be doing it for them, which isn’t necessarily a bad thing, but it’s different when both of you are in love with each other’s work. Who I work with now… it’s deep relationships. Ye, Steve Lacy, Paris Texas. Those relationships are really hard to find, so I would rather nurture the creative relationships I have. I’m not saying I’m not open. I'm open to all types of things, but I’m not really fishing for “work.” That mindset of no commissions helps me attract what I want.

CKE: You also told me that you’ve been reflecting a lot about having worked to a major extent for other people, and that you maybe want to focus more on your own projects and art. Why is this important for you? What’s the difference between creating your very own work versus collaborating or creating for others?

AT: I spent half of my life, basically since I was 15, creating for other people.

For the past 15 years, it was the most important thing—a receptive circle. And I don’t love art—not like I love my daughter or my mother, at least. And it definitely doesn’t love me, but at least it can never leave me. Until I leave here.

At this point would rather do the interior design of my daughter’s room than design something for an artist. I feel more from watering my rosemary bushes or shadow boxing or doing push-ups. I’m maxed out and don’t wanna do this anymore or at least like I used to.

Maybe it will come back, I don’t know.

I just have an intuition and an instinct to create—I guess the same way a bird has an instinct to fly, but does it really love flying?

Creating forces you to dive into a deep dark place, not always bad places, but it can be very intense for me and self-reflective. And it’s tough to climb out of.

Even though I haven’t really made anything that amazing, if I died tomorrow, I would be satisfied with my catalogue and my collaborations, and what I’ve been able to give to the world before 30.

Credits

- Creative Direction: AUS TAYLOR

- Text: CLAIRE KORON ELAT

- Photography: AYSAN LAMBY

- Photography Assistant: KOFI JOHNSON

- Set Assistant: AGNES MAGGIE SHU

Related Products

Related Content

“I AM THE LEADER”: YE (KANYE WEST) in Conversation with TINO SEHGAL

Where in the world is Paris Texas?

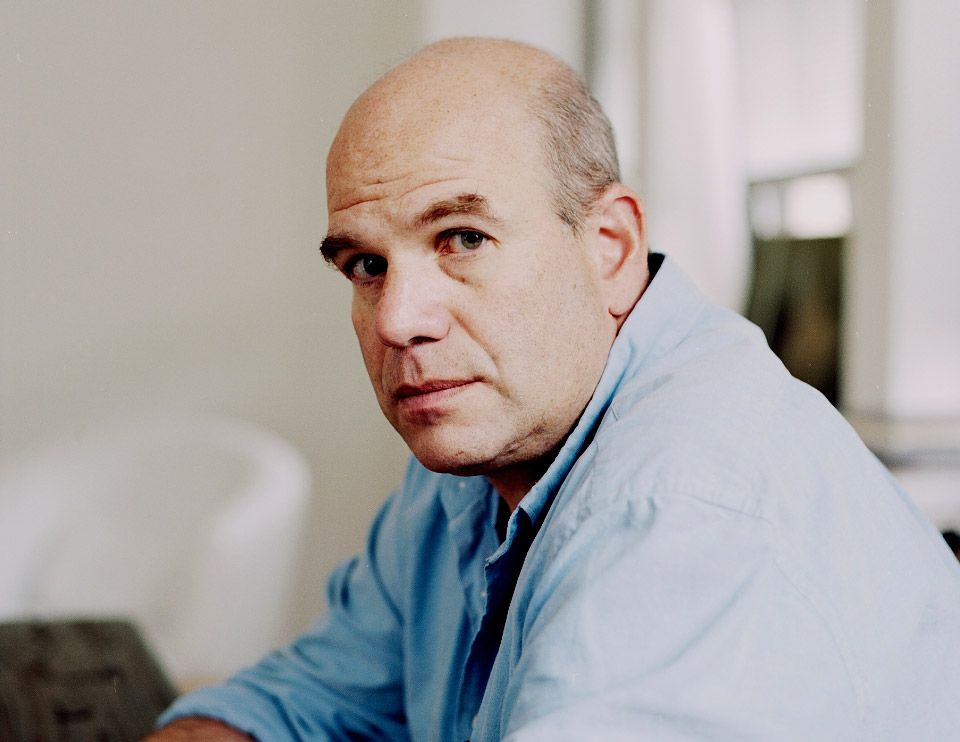

Salty, Litigious, Iconoclastic: DAVID SIMON on TV as discourse

CALABASAS

An Interview with Stanley Kubrick’s Producer and In-House German JAN HARLAN

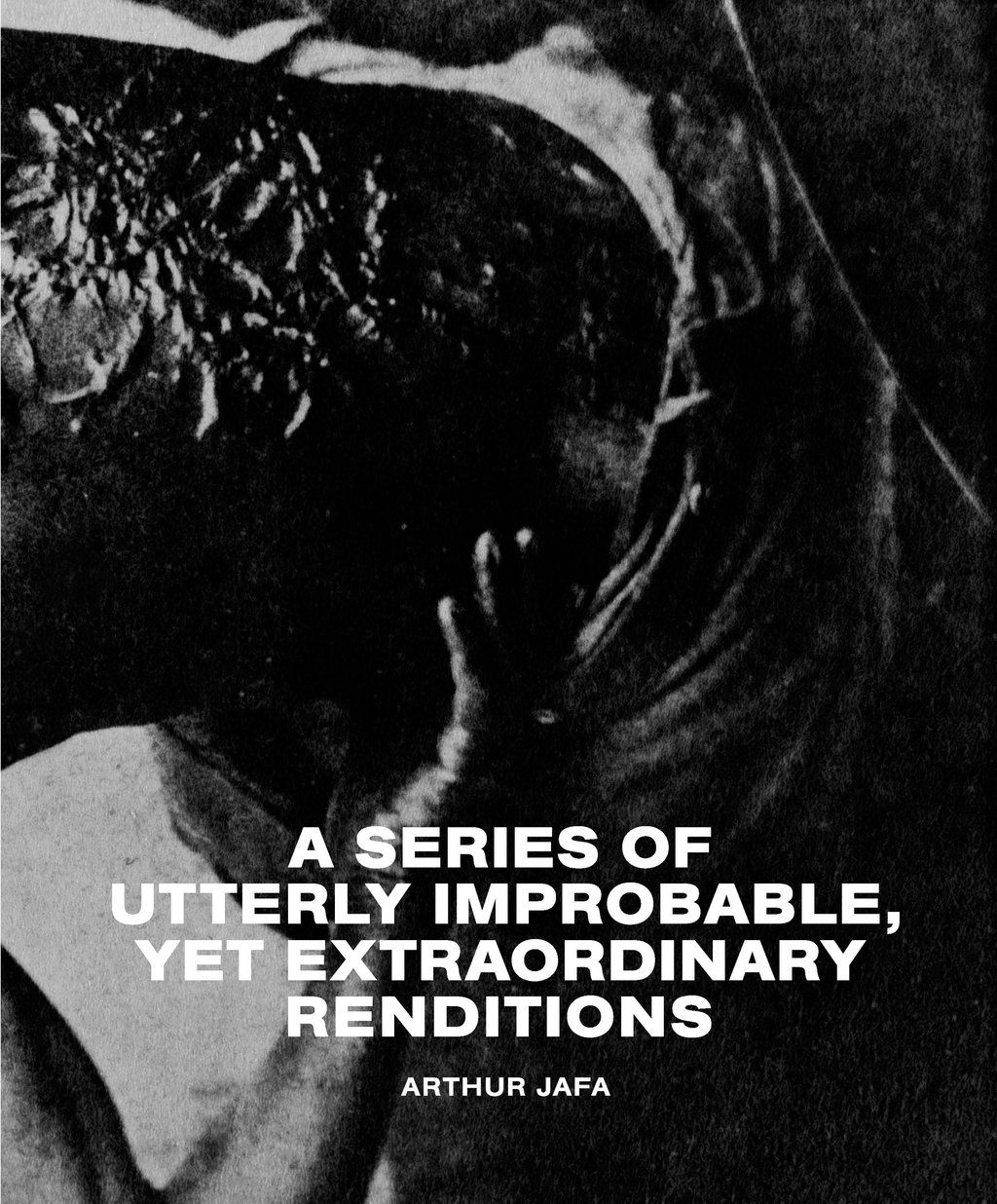

ARTHUR JAFA INDEX: A Series of Utterly Improbable Statistics

Who Is an American Artist?

Yeat: American Truths

LANCEY FOUX: Purple Reign