An Interview with Stanley Kubrick’s Producer and In-House German JAN HARLAN

For more than thirty years, JAN HARLAN worked alongside Stanley Kubrick as the director’s researcher, confidant, and producer.

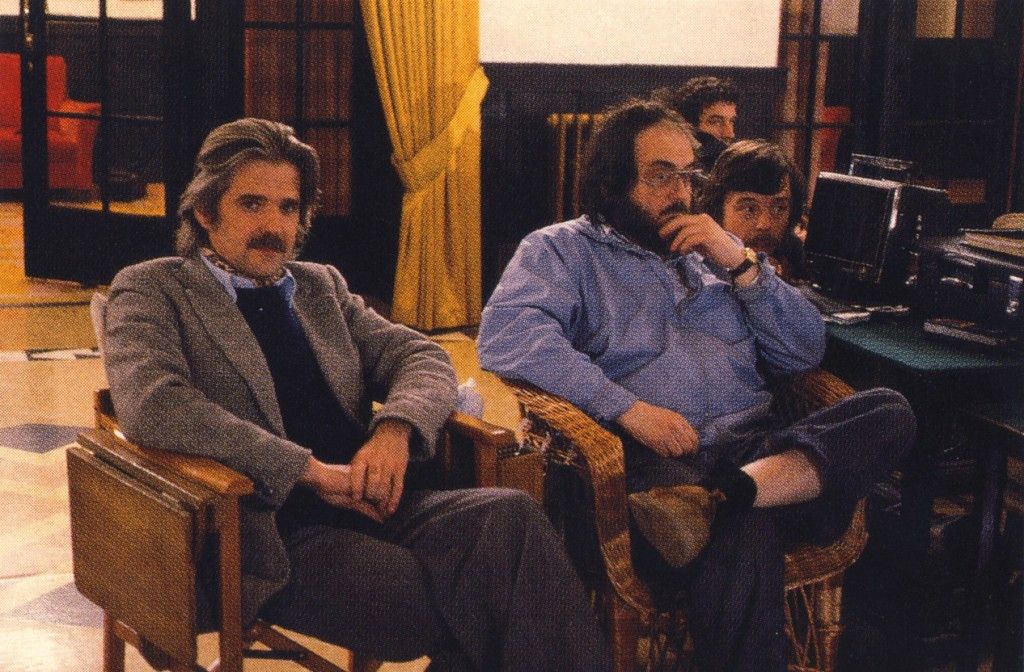

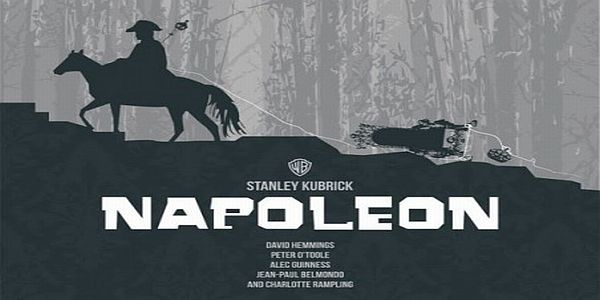

Introduced to Kubrick in 1968 through his sister Christiane, Kubrick’s wife, Harlan began work as Kubrick’s resident German-speaker and travel companion, accompanying the director to Romania to assist in the pre-production of the never-realized epic film Napoleon (German proving a more useful negotiating tool in the then-Socialist republic). He would go on to produce all of Kubrick’s films from 1975 up until the director’s death in 1999.

Following Kubrick’s death, Harlan directed the definitive documentary Stanley Kubrick: A Life in Pictures, which brought together friends and collaborators ranging from Woody Allen to Shelley Duvall. He has since continued to act as an archivist for Kubrick’s vast body of work, and has most recently assisted in the creation of a travelling exhibition of Kubrick’s work, its 12th iteration having just finished at the TIFF Bell Lightbox in Toronto. 032c sat down with Harlan to discuss legacy management, unfinished projects, and Kubrick’s favourite German film.

DARRYL NATALE: You’re seen as a kind of a spokesperson for Kubrick. How did that come about?

JAN HARLAN: After Stanley’s death, I was asked by Warner Brothers to do this documentary about him. I was very happy that they did that. I was not an established documentary filmmaker, but they knew that I knew Stanley very well – and that I worked with him for 30 years – so they asked me.

Then came the exhibition, which was initiated by the film institute in Frankfurt. They sent an archivist to help sort out what would be useful for an exhibition, but I was instrumental in selecting the items on exhibit. It’s a selection of things both for the casual viewer who’s a bit nosy and interested as well as for the scholar who really wants to get into the details.

What considerations do you make when deciding what elements of Kubrick’s life should or shouldn’t be shared? Do you feel a sense of responsibility to maintaining a specific image of Kubrick’s legacy?

The factor is always the same: make it interesting for the recipient. That’s the number one rule. I’m not an artist, but it’s also true for an artist’s work. It was as true for Shakespeare as it was for Kubrick. Even the most serious film has to have an element of entertainment or nobody wants to watch it.

When I was shooting the documentary, I only wanted people who were really competent at talking about Kubrick – the people who worked with him and who knew him intimately. Otherwise, I wasn’t interested in their opinion. I also wanted to have people that Stanley liked very much – that’s why I interviewed Woody Allen, Martin Scorsese, and Steven Spielberg. The only person I couldn’t get was Ingmar Bergman. Everybody else I asked came on board, and there were many many more that I couldn’t put into the documentary because it’s very long as it is.

For me it was very therapeutic to realize how many people appreciated and liked Stanley so much, even though they might have had a hard time sometimes. I interviewed the focus puller, Doug Milsome, who really didn’t always have an easy time, but he said he wasn’t going to say anything negative because it was the best thing he ever did. It helped his career enormously.

There have been a few films in the past year that have been called “Kubrickian”. What do you think of the term?

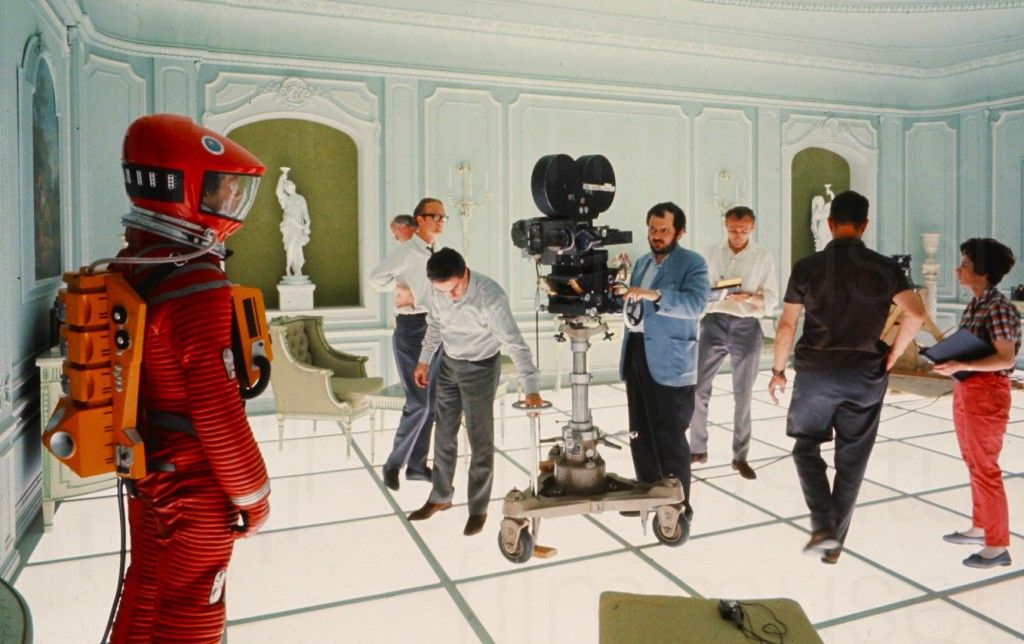

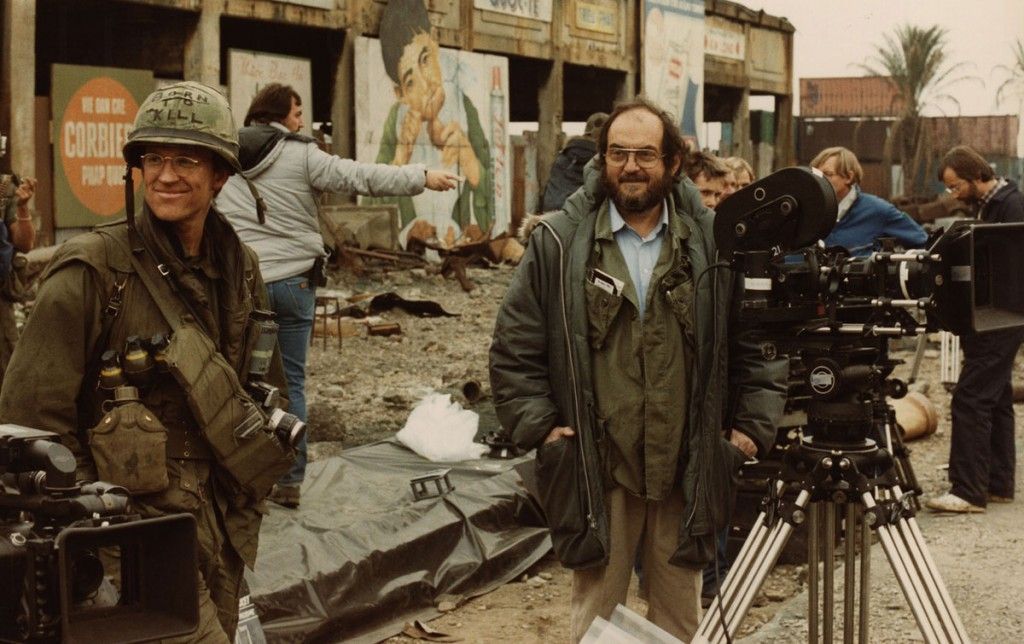

It’s not an adequate word. Kubrick had his own handwriting, that’s true, but the greater the profile of an artist, the more this handwriting is developed. They all have their own handwriting just as painters have their own style. You recognise a Van Gogh or a Velazquez because they are developed to a level where you recognise their handwriting. Stanley’s films were done with tremendous care for every detail. He was so careful and self-critical.

The great thing about Stanley’s work, like that of any great artist, is that his work doesn’t disappear. Paths of Glory or Dr. Strangelove could have been made yesterday. You could say the same about Ingmar Bergman, Akira Kurosawa, or Edgar Reitz.

You often mention Edgar Reitz in the same breath as Kubrick when speaking about how his work endures.

Heimat is the greatest post-war German film. I saw it with Stanley and I remember him turning to me after it was finished and saying “I don’t believe it. Did you see that? I’ve never seen anything like it.” Unbelievable. Edgar Reitz was a pioneer of what’s happening now with television series. It endures because it’s great art.

What do you know about the 18th century? You know it through films, writers, painters, composers, and architects. Without the artists, we would be completely ignorant. You can study kings and wars and territories, but the first thing you discover about a certain period in time is always through the artist. I wouldn’t know anything without Dickens and Austen. If you want to know about Germany, read Buddenbrooks by Thomas Mann and watch Heimat by Edgar Reitz. Stanley was floored by them.

Almost all of Kubrick’s films were adaptations – what was his criteria for choosing a story?

He had to love it. Without that, it was a non-starter. He could fall in love with a book, and he could fall out of love. And that’s really the right term. It wasn’t, “Oh, I find it interesting.” That’s not enough to devote three years of your life to. You have be passionately in love; only then is there a chance of lifting it out of the ordinary.

What would make him choose one book over another? There are stories of him throwing books across the room after the first few pages or turning movies off after 20 minutes if he didn’t like them.

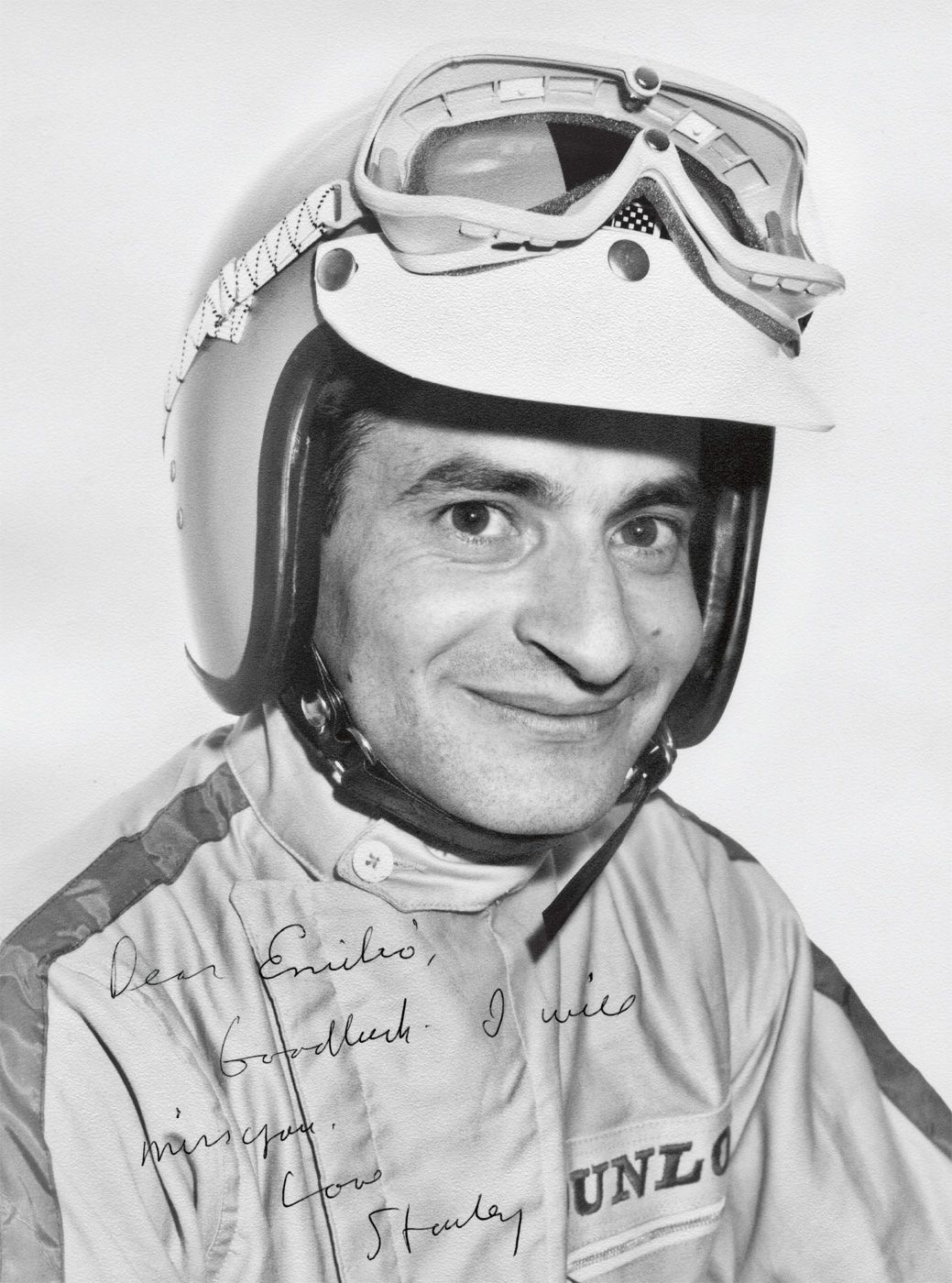

The film story is true – after the first reel, typically. On the weekend, he would set up his own cinema at his house in Abbots Mead. Emilio, his driver, would pick them up from the various distributors. He would have seven films sitting there from the weekend, and if the first 20 minutes were dull, he wouldn’t take the risk of wasting two hours. That’s not a bad idea.

I always feel guilty if I can’t finish a movie.

No guilt. You’re absolved. It’s up to the filmmaker to make sure that doesn’t happen. If the filmmaker is so pompous and unable to relate to the audience in the first twenty minutes, then you’re absolutely well advised to walk out. I think that’s fair.

There are a few films that Kubrick had planned to make but never finished. What would make Stanley fall out of love with a film? Was this the case with Napoleon?

Absolutely not. He worked for two years on Napoleon. That’s how I started with him. It was MGM that pulled out. Dino de Laurentiis had greenlit a film project called Waterloo with Rod Steiger as the lead. It was a Soviet-French-American co-production. MGM didn’t want to take the risk of Kubrick following Waterloo with another expensive film – it was a business decision. Kubrick was very depressed for two weeks because he’d been gearing up to it and had become a scholar on the French Revolution. But then he moved on. The film would have fitted so well into his body of work. It was a film about a man who was colossally successful: he made France rich, was loved, had great charisma, but was a fool and vain and arrogant and had nobody to blame for his downfall other than himself. That’s what was relevant for Kubrick because it still happens today.

Baz Luhrmann might direct the film after all.

I’m in touch with Steven Spielberg about it. We talked about it, and with the new onslaught of the long dramatic serial form on TV, it would work perfectly. Steven thought Baz Luhrmann would be a great director for it. HBO was interested in doing it, but MGM owns the rights, so the lawyers have to sort it out.

Have you been involved in the pre-production? How do you ensure it stays true to Kubrick’s original vision?

Me? I can’t. I’m not an artist. I can only help by supplying what I know. I can make a documentary – that’s about diligence and planning. But you need to be an artist to make a work of art. Film production is a manufacturing industry, but you need an artist to make a work of art. The rest is manufacturing.