Anti-Villa: ARNO BRANDLHUBER’s Thinking Model for a New 21st Century Architecture

Look at this thing. The windows don’t resemble anything, except perhaps the setting for the French film Themroc (1973). People stand on the roof, without a railing, backlit by high-contrast light. A little later, rain starts falling and the whole group disappears, slipping down one story, visible through the windows that look like eyes – set deep in the Anti-Villa. The noise echoes down to the emptiness of the lake, then suddenly water shoots over the roof, a violent stream that disappears noisily into a bed of gravel. What does it all mean? What is the Anti-Villa, and who are all these people gathered here, southwest of Berlin on a warm Saturday night? What are they doing?

But first things first.

The “Ernst Lück” underwear factory was built sometime in the 1960s on a prime waterfront spot in one of the most attractive bays off of Lake Krampnitz. The state-run enterprise occupied a compound consisting of two long buildings of three stories each, offering a total of 700 square meters of manufacturing space. A few meters beyond the buildings, at the water’s edge, workers and weekend visitors shed what was once made here: undershirts and underpants. The buildings were one of the many unintentionally surreal places in the GDR – in this case, an underwear factory overlooking a nude beach. After the fall of the Wall, the company was liquidated, while the empty buildings stayed behind. Dubious production companies made soft-core porn films on the site. The waterfront property went to seed. Windowpanes were broken. Speculators bought the land, intending to tear down the factory buildings and build “villa-style” detached houses, but they never got the money together. And so the underwear factory buildings managed to stay standing.

There are two typical ways in which utilitarian buildings left over from the GDR are dealt with. Owners either tear them down and replace them with something they find appropriate to the setting – a “Villa Park on the Water,” or its equivalent. Or the owner pours money into energetically optimizing what’s already there, wrapping it in state-of-the-art insulation, and – as part of this rather lavish exercise – trying to adapt it to contemporary notions of what makes a house attractive and aesthetically pleasing.

When Arno Brandluber bought the property in 2012 with two journalist friends, he did neither. He made relatively few changes to the existing long building, creating a paradigmatic Denkgebäude: The Anti-Villa.

Prefab house manufacturers, in their catalogues, sell “villas” – relatively simple, single-family homes, dressed up with various architectural flourishes that are meant to lend the whole thing some dignity. These might include a columned entryway and a baroque-style avant-corps that evoke classical “villa” structures. The Anti-Villa is a manifesto against this ideology, against home improvement as a prettifying exercise. Brandlhuber realized that turning the ugly building into a Bavarian-style country residence or a modern lakeside mansion à la Herzog & de Meuron would be an insane undertaking. So he developed a new methodology of repurposing the existing structure.

A NEW METHODOLOGY: LOW-TECH ZEN

Brandlhuber’s approach incorporates a new concept of resilience. Instead of insulating the structure with an enormous Dämmputzfassade to ensure that the whole thing stays cozy and warm in sub-freezing temperatures, in winter the Anti-Villa’s 500 square meters can be scaled down to 70 easily-heated square meters. The heat comes from a sauna in the middle of the first floor.

When it was built, the underwear factory served as a testing area for construction workers. Each had to show that he could install a window; each of the windows on the long exterior walls was put in by a different worker. It was thus a kind of proving ground for architecture, and in a certain sense it is still an exercise ground, a place to develop new ways of thinking about the discipline. Brandlhuber often asks his students to take the trip outside the city to participate in lectures and conferences.

The Anti-Villa is living proof that architecture can mean more than combining and bonding together materials at great effort and cost. It can mean taking something out of an existing format and digging into it to make it more porous. Brandlhuber got rid of all supporting walls in the interior. The upper floor became a kind of covered open space, almost like a big field. A functional core for the house was established here, with a bathroom and a kitchen unit and a sauna. The sauna takes the place of a fireplace, the meeting point of different temperature zones that get cooler the further one gets from the center. This area contains what might be called “tents.” Transparent curtains made of PVC sheeting define the boundaries of different zones. As architectural theorist Anh-Linh Ngo has remarked, the result is a reiteration of Reyner Banham’s concept of “architecture of a well-tempered environment” – in this case, a low-tech strategy for implanting an ecological and economically sustainable solution in a given environment. At the same time, the room’s atmospheres are radicalized. In summertime, the house is a summery, open landscape. You sit in the windows as if under a cliff. In the winter, the radical reduction in living space creates a sense of coziness:

The house intensifies seasonal impressions, instead of blocking them out with high-tech methods. Considered this way, it’s a bona fide Smart Home.

INTENSITY

We might even speak of the aesthetics of intensification: the space intensifies the sensation of seasonality. The water spout makes the rain louder, the stream of water over the roof thunders down with more volume when it lands on a gravel bed. Here, everything seems bigger.

RESILIENCE

The idea of an architect as a figure who inscribes himself in nature and turns its energies to his own advantage, rather than trying to overwhelm nature by force, is also on display in Brandlhuber’s latest project in the Rockaways section of outer New York City. In 2012, Hurricane Sandy created tidal waves that destroyed many wooden houses on this low-lying peninsula. Now builders have undertaken the complicated and energy-intensive project of hoisting these houses on pedestals, with concrete walls for improved flood protection. Brandlhuber has chosen another approach. He takes a fragile, still-standing house and builds a casing inside the walls, filling the space between the house walls and the casing with concrete. The exterior is then peeled off like an eggshell. The result is an afterimage, an imprint in the concrete, like a footprint in the sand. The house’s fixtures are collected in a mobile unit, which can be transported to the mainland if a storm threatens the house. The concrete shell is not affected by floodwaters; it’s like a grotto that dries after the waters recede. The extraordinary efforts people undertake, mainly in vain, against the rising waters (sandbags, water pumps for the basement), and the aftereffects of a flood (ruined overstuffed sofas and household appliances) – are suddenly non-issues.

Brandlhuber has created a kind of Petit Trianon across from the Anti-Villa, a prototype for this intelligent way of inscribing oneself into one’s context: It’s a guest house built on the site of a ramshackle old service building. Brandlhuber built an interior concrete shell and gave it the name “Rachel,” in honor of Rachel Whiteread’s cast sculptures.

RAWNESS AS A SOCIAL QUALITY

The Anti-Villa’s aesthetic credo is to make the rough even rougher. The coarse GDR-era stucco exterior is conserved, given even more intensity with a cold gray shade of paint. In radicalizing the character of the existing elements, Brandlhuber has become a loving conservationist. But the cult of roughness and anti-taste is not just an aesthetic position – it is also a challenge to the social core of architecture.

Brandlhuber demonstrated how to produce stunning effects with minimal materials in a building he designed on Berlin’s Brunnenstrasse, which also housed the 032c Workshop. A raw street-facing concrete sculpture in the center of Berlin, covered with hothouse glass panels, it is built on the ruins of a failed investor’s idea of an architectural showcase. “The façade is a social instrument, not an aesthetic one,” explains Brandlhuber. Full-on renovations are often a tool that aids in evictions. A renovated house, perfectly insulated from the outside world, is often unaffordable to many of its original tenants, effectively shutting them out. “The segregating model of the modern city is reflected in these façades,” says Brandlhuber. The Anti-Villa’s façade, in contrast, must be read as a social manifesto. The most striking aspect is the windows, which look like they were bashed into the exterior in a moment of spontaneity.

WINDOWS

At first glance, the windows are the exact opposite of the windows installed by the apprentice workers in the original façade. The originals bear the imprint of fear – the fear of the apprentice who might do something wrong, install a crooked window, a wrong window. These “practice windows” are the result of a collective effort in which each individual worked against everyone else in order to install the best possible window: A result of competition. Brandlhuber removed the pitched roof, which was made of corrugated asbestos sheets, and replaced it with a newly conceived flat one that is structurally designed as a casing. This allowed him to cut openings five meters wide in the existing wall. The openings were created during a kind of hammering orgy – dozens of friends gathered to beat away at the wall and construct the holes. It’s a stunning contrast: Generosity and the gesture of tearing something open, in stark contrast to the sweaty, oppressively tiny squares of the GDR. Compared to the tendentious striving for perfection of Swiss concrete minimalism, it presents an almost casually improvised aesthetic, one with a sense of both heft and looseness.

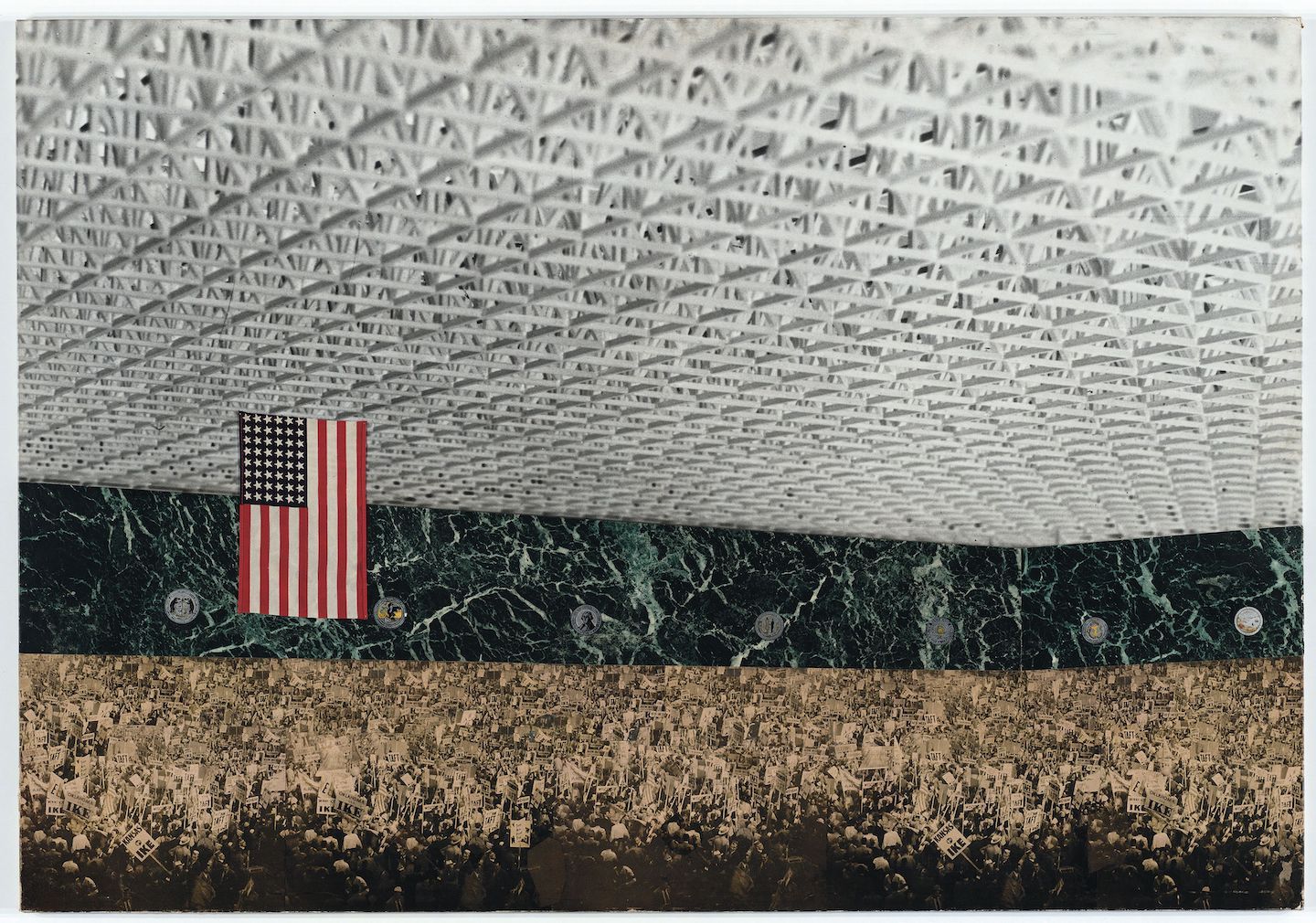

The hammering functioned as a de facto Happening, an event with obvious references in the history of art and film. In the movie Themroc, the actor Michel Piccoli makes similar “openings” in his apartment. His neighbors imitate him, resulting in a vast, dark, orgiastic world where the holes in the walls signify the drives of an uncontrolled society that no longer accepts officially sanctioned boundaries between private and public, intimate and collective space, and the limits of the body. The Anti-Villa refers to a similar culture of uninhibited spatial decomposition. In a way, it’s not architecture. It’s orgytechture.

We find another, related system of references in the spatial openings created by Gordon Matta-Clark: His sliced open homes are echoed in Brandlhuber’s staircase that leads from the entry to the roof, veritably cutting the building in half. The windows make you think of Matta-Clark’s “cut-outs.” Matta-Clark himself has been misunderstood as of late, but every construction team that hammers out variations of the now infamous Conical Intersect (1975) becomes a kind of ideal society for the length of that project. Both Matta-Clark’s restaurant “Food” and the ‘cut-outs’ offered a new idea of collectivity and society, situated in time.

THE ARCHAIC MALAPARTE

When discussing “raw” buildings, it is impossible to avoid mention of one of the most famous houses of the 20th century. For instance, Brandlhuber uses a huge slice of a tree-trunk as a table. Next to it, a fur rug lies on the raw concrete. Then there’s the long staircase that cuts straight through the building and up to the roof, which serves as a terrace to look out at the water. Every element, from the roof terrace over the little windows to the arbitrary mixing of the archaic and the modern inside the structure, is reminiscent of the Casa Malaparte in Capri. At the same time, the windows are also a blurry formal references to Capri’s blue grottos, and the outer rooms seem to take their cues from the spaces wherein Michelangelo Antonioni set his films. Set up with tables, the space between the two buildings has proportions similar to the Piazetti of old Italian towns. In a way, the Anti-Villa is informed by a different, deeper idea of Italianitá and Villegiatura, as opposed to the terracotta-colored prefab houses marketed as “villas.”

RUINS

And you cannot look at the windows without thinking of fake ruins – specifically of the architecture of the nearby Pfaueninsel, or Peacock Island, a perfect product of the German obsession with antiquity, built in the reign of Friedrich Wilhelm II. The “castle” is supposed to recall a dilapidated Roman country estate house. The history of the concept of the villa sprawls from the early Renaissance Tuscan villas through late Renaissance mansions of Veneto, to those of the early and high Baroque period, a day’s carriage ride from Rome in places like Frascati and Tivoli. It is the story of an obsession with the ancient idea of villegiatura. This dates back to Scipio Africanus, who lived in the second century BC. He built himself a villa in Campania where he not only retreated from society, seeking relief from the tumult and pressure of dealing with political rivals, but also enjoyed a Greek lifestyle with his many friends, away from the public duties and behavioral codes of Rome. He established a life of readings and feasts, another idea of communality.

The Renaissance villas, especially those in the Veneto, were not idyllic retreats, but rather the sites of intensive production in a moment of historical crisis, as Reinhard Bentmann and Michael Müller have shown in their reference work The Villa as Hegemonic Architecture (1970). The city of Venice’s wealth was based on its control of the overland route to India and East Asia, which led through Arabia and North Africa. After the discovery of a direct sea route, the city’s dominion over land trading was suddenly superfluous, and their economy was hit hard. In 1520, Venice was no longer the richest city in Italy – it fell to third place behind Rome and Genoa, which was better situated to take advantage of trade with the Orient. Banks and trading companies went bankrupt, and there wasn’t even enough money to import grain. This forced Venetians to turn to the fields, and a cult of the pastoral (Sancta Rusticitas) came into play. Having turned to the land that lay between Padua, Treviso, and Verona, former Venetians created virtue out of necessity. They papered over the forced agrarianization of society by taking their references from Roman villa culture. The villas of Maecenas and Lucullus became ideals: A painting in the Villa Maser shows the Nuovo Parnoso, Paolo Veronese’s landscape of idealized ruins, showing a ferry to the Stanza of della Lucerna.

THE VILLA AS MIGRANT

Most of these ancient villas were migrants. They brought elements to the countryside that someone had seen somewhere else. Lucullus’s villa was the ultimate example of this migrating quality. He had studied garden art in the conquered cities of Persia, and built gardens and villas in Rome and Naples that incorporated these foreign elements. Precious sculptures adorned the buildings, as did cherry trees, which in time spread all the way to Britain. But above all, the villa embodied a social promise. As Antonio Francesco Doni wrote in 1566, “Out the windows you see carriages streaming from different directions, all coming just to visit your villa, and to visit you. You see the most beautiful women, the free landscape, gardens, outdoor banquets, dances, and varied delights. Thence comes the fragrance of flowers into the garden and expensive perfumes.” This promise of Villegiatura informs the notion and the dream of the villa, even in its most emphatic negation.

COLLECTIVITY

The Anti-Villa is also true to name in the sense that it sets up an alternative to the modern ideal of the country house. An alternative to the house asa retreat from the less privileged, a place to hide from city life. Instead, it presents the ideal of a communal space. This is set against the backdrop of the many renovated villas that dot Potsdam’s outskirts, all fixed up by a neo-conservative haute bourgeoisie in buildings that served as children’s homes and other institutions in the GDR. In a pathetic side-note, some residents now refer to the lakeside towns of Sacrow and Krampnitz as “Kramptons,” a comical

tribute to the exclusive Hamptons on New York’s Long Island.

The Anti-Villa presents an alternative to this re-privatization – a core that is defiantly public. It refers back to the idea of the village, which is present in the very word “villa.” The Anti-Villa can serve as a bedroom for the architect – there’s a singular bed in the empty upper floor – but it can also be a village. It can host conferences, seminars for Harvard students, public discussions of the future of urban construction, as well as feasts and parties. It proposes the idea of an intensified collective, the other side of the urban fabric, more concentrated, precise, free of pre-conceived ideas about society, following the example of predecessors like Black Mountain College. Against the backdrop of other Potsdam mansions, it imitates Fourier’s Palais Social, a Phalansterium set against Versailles. The buildings have similar dimensions, but different contents. The Anti-Villa is a kind of summer Phalansterium, a place where thirty people can camp together. In an era when a “villa” is just a dressed-up single-family home,it brings to life the collective nature of the Villegiatura, as seen in Giovanni Antonio Fasolo’s 1570 painting of feasts and festivals in the Villa Caldogno. Or, as Palladio put it, “A house as a city in miniature.”