Life Exists: Theaster Gates’ Black Image Corporation

|Victoria Camblin

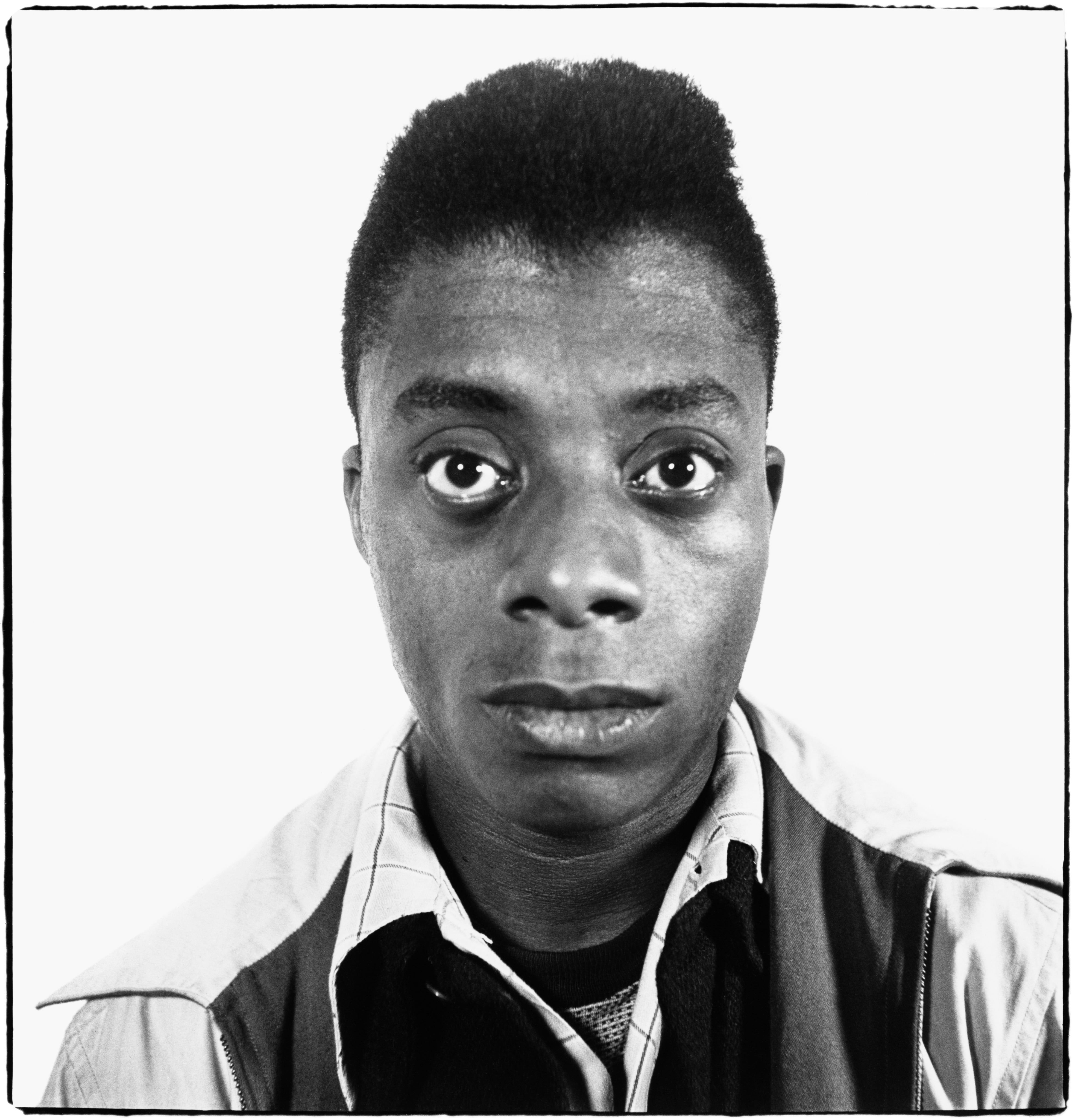

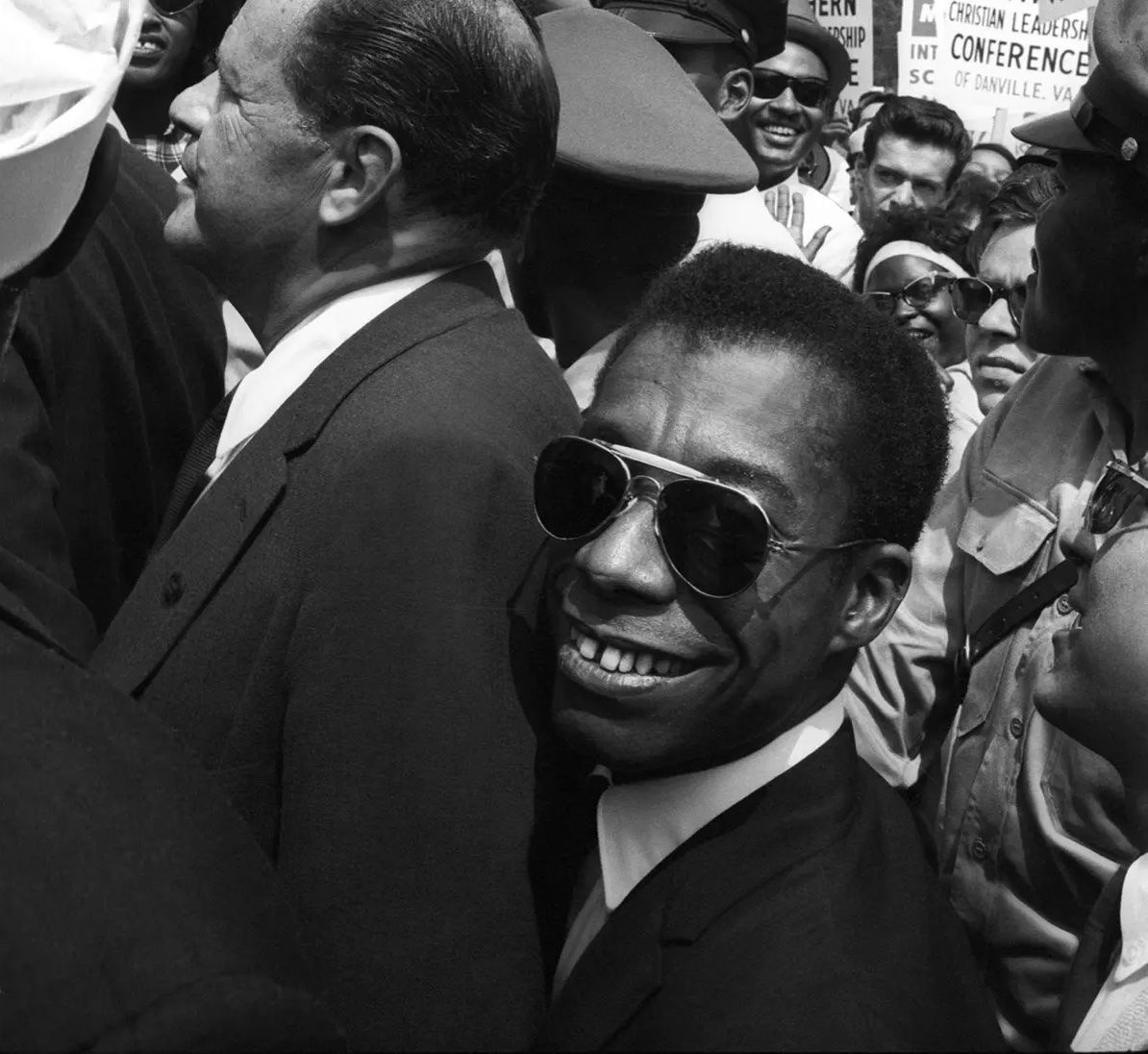

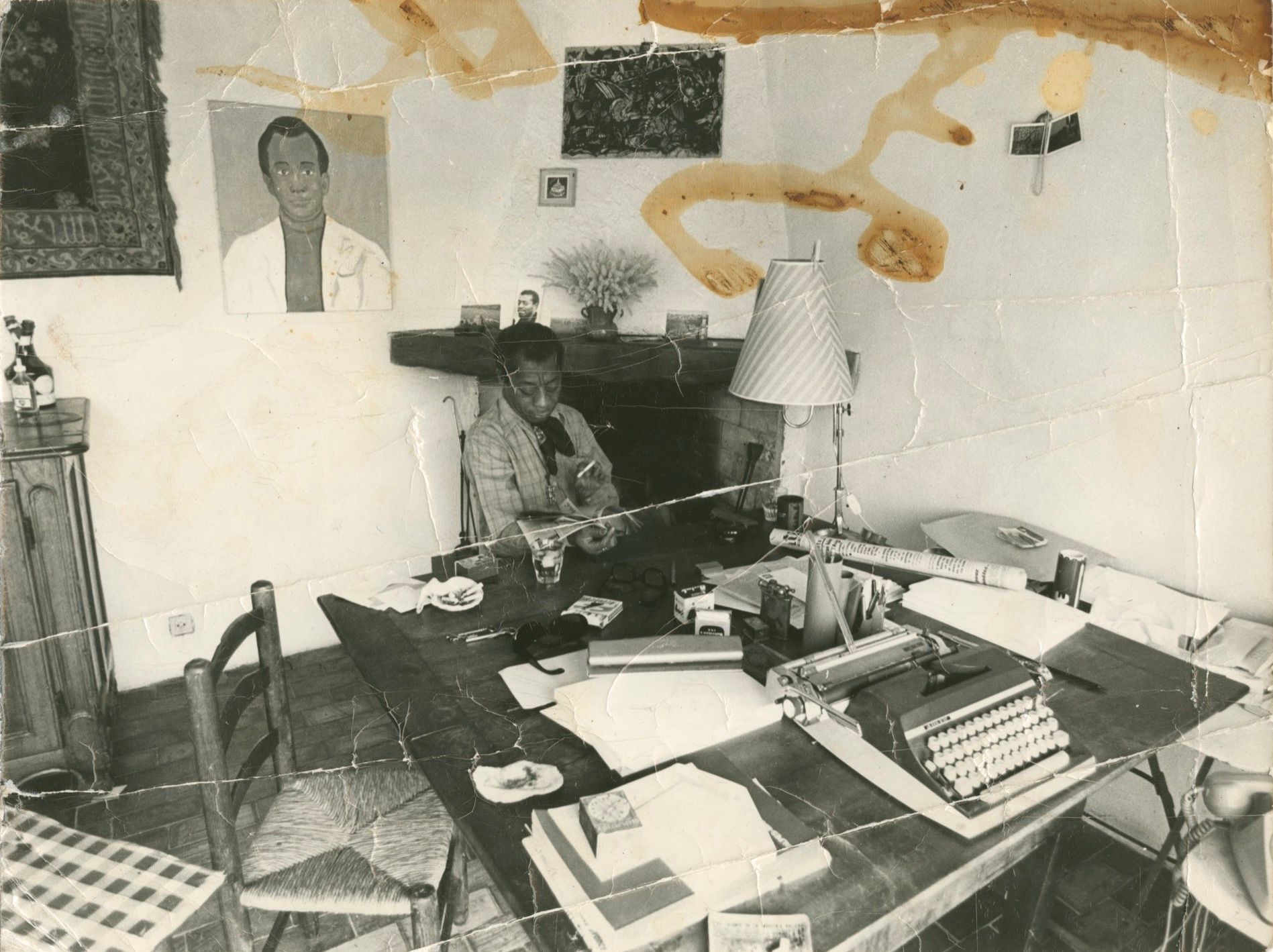

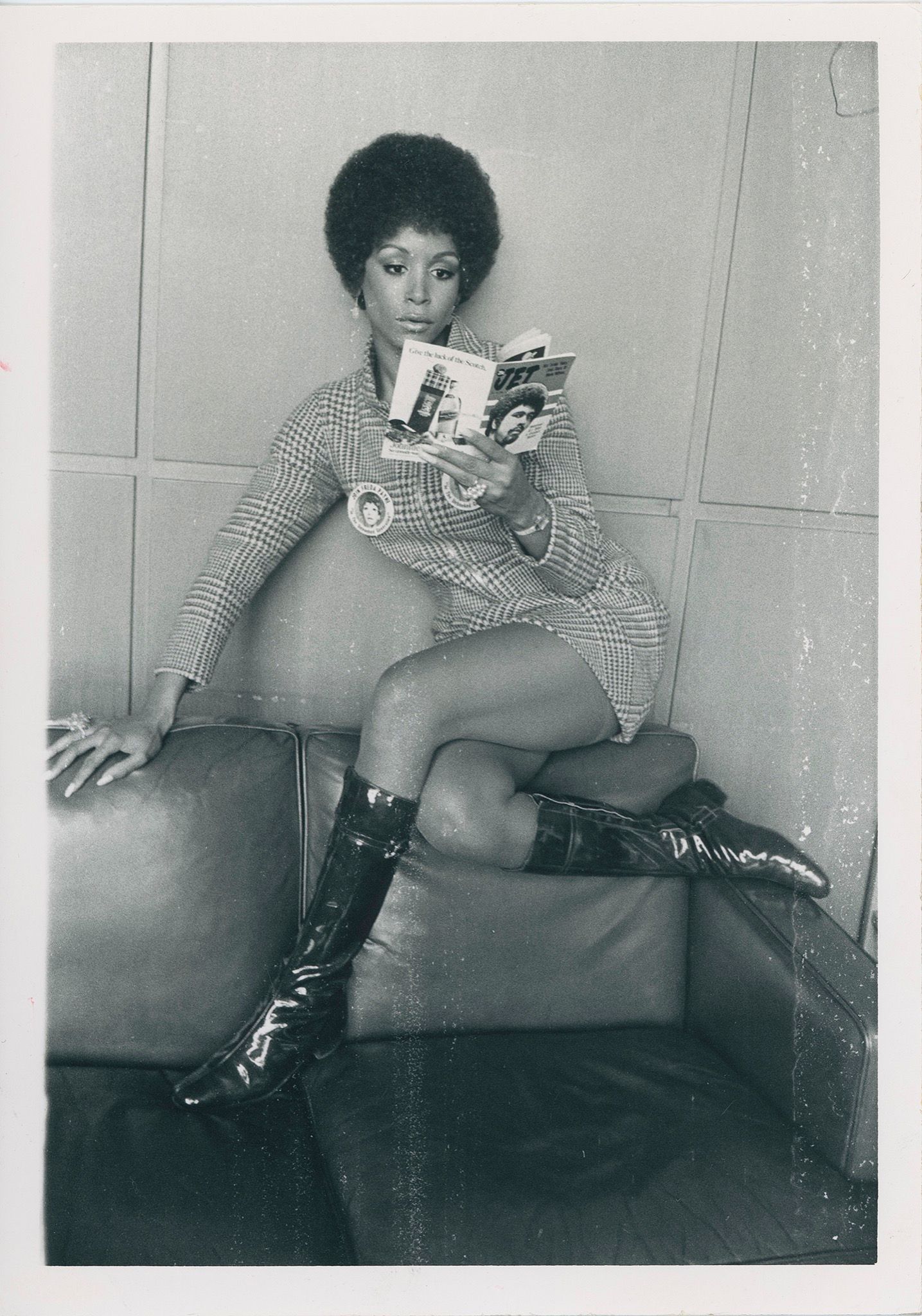

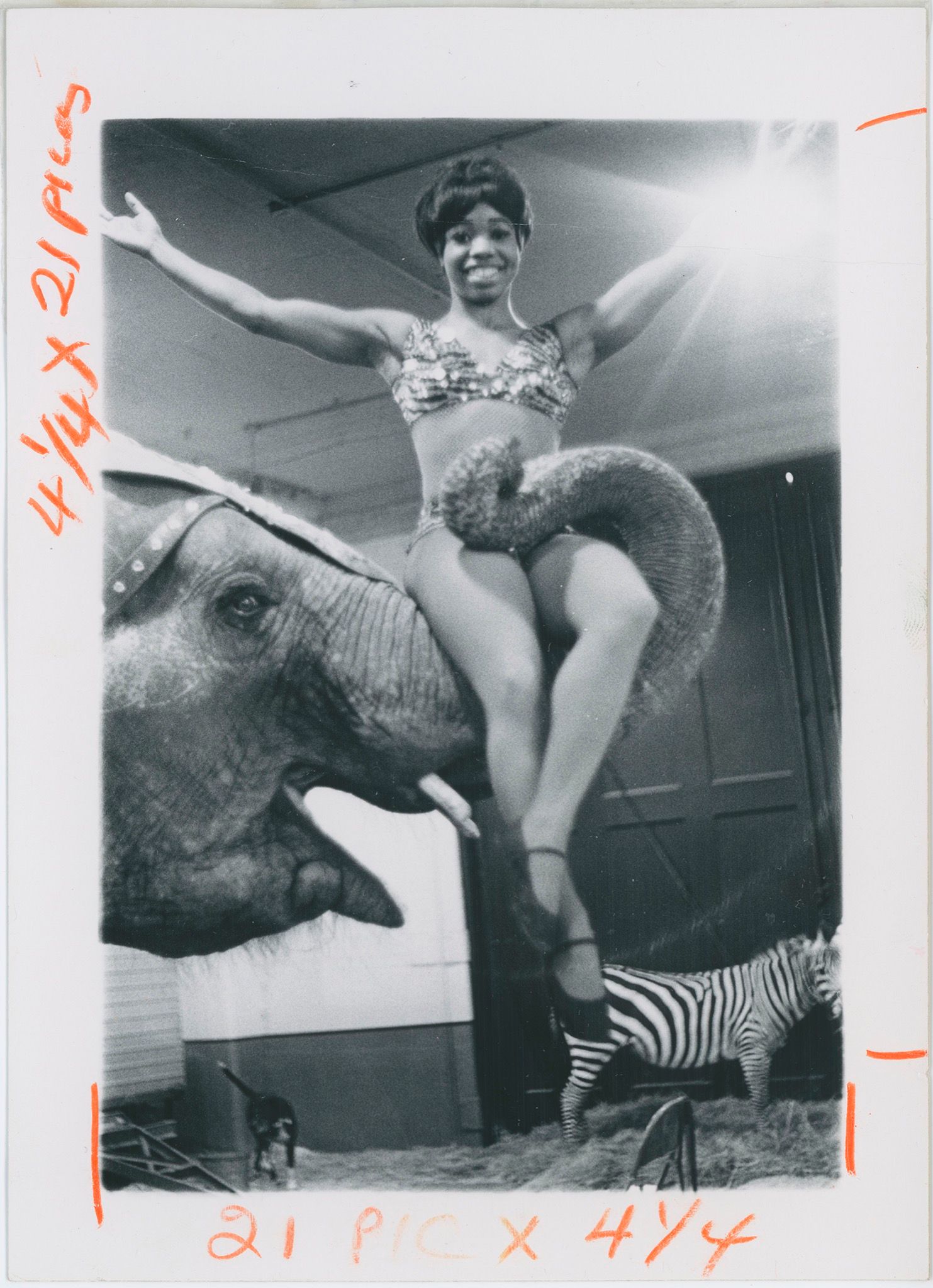

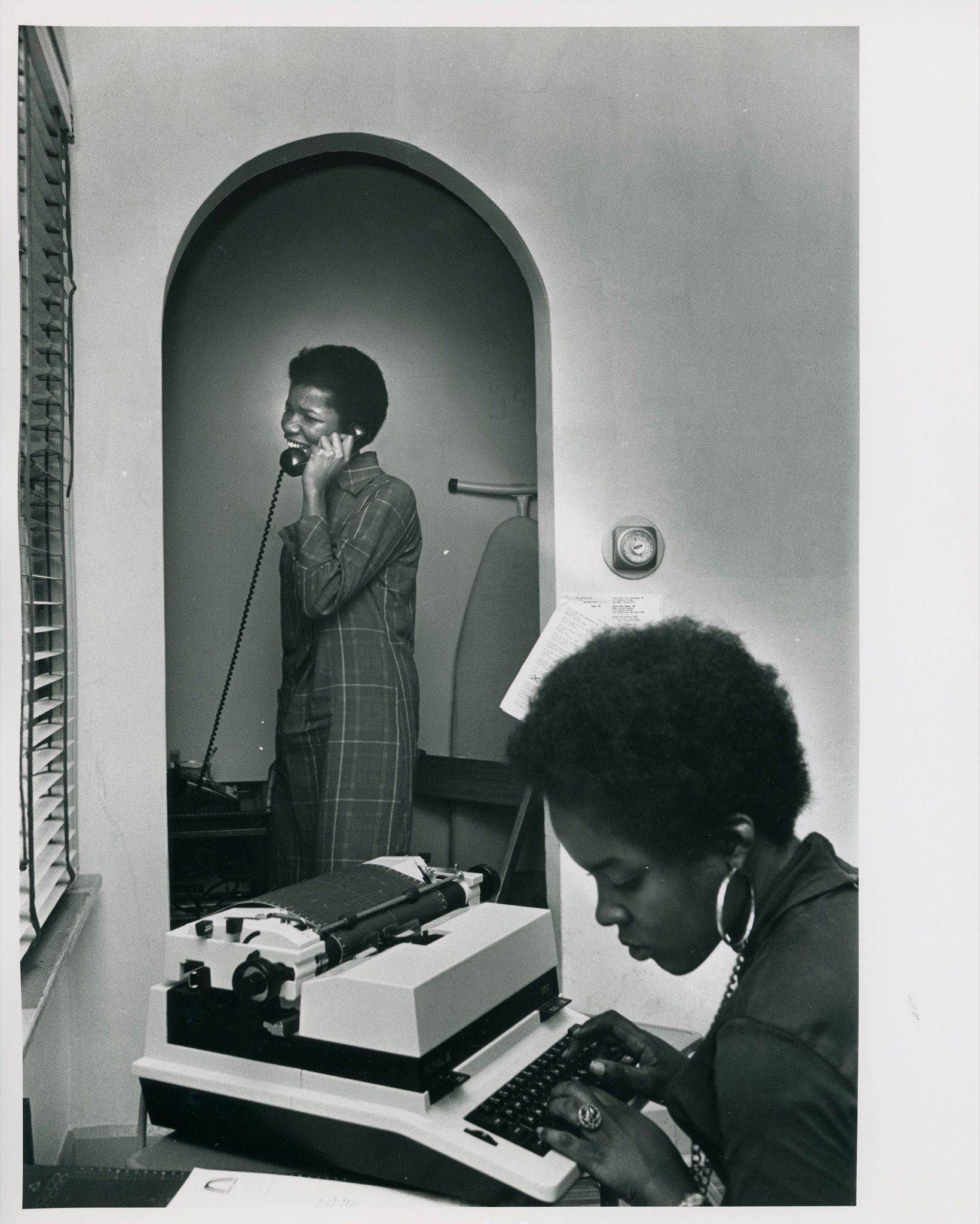

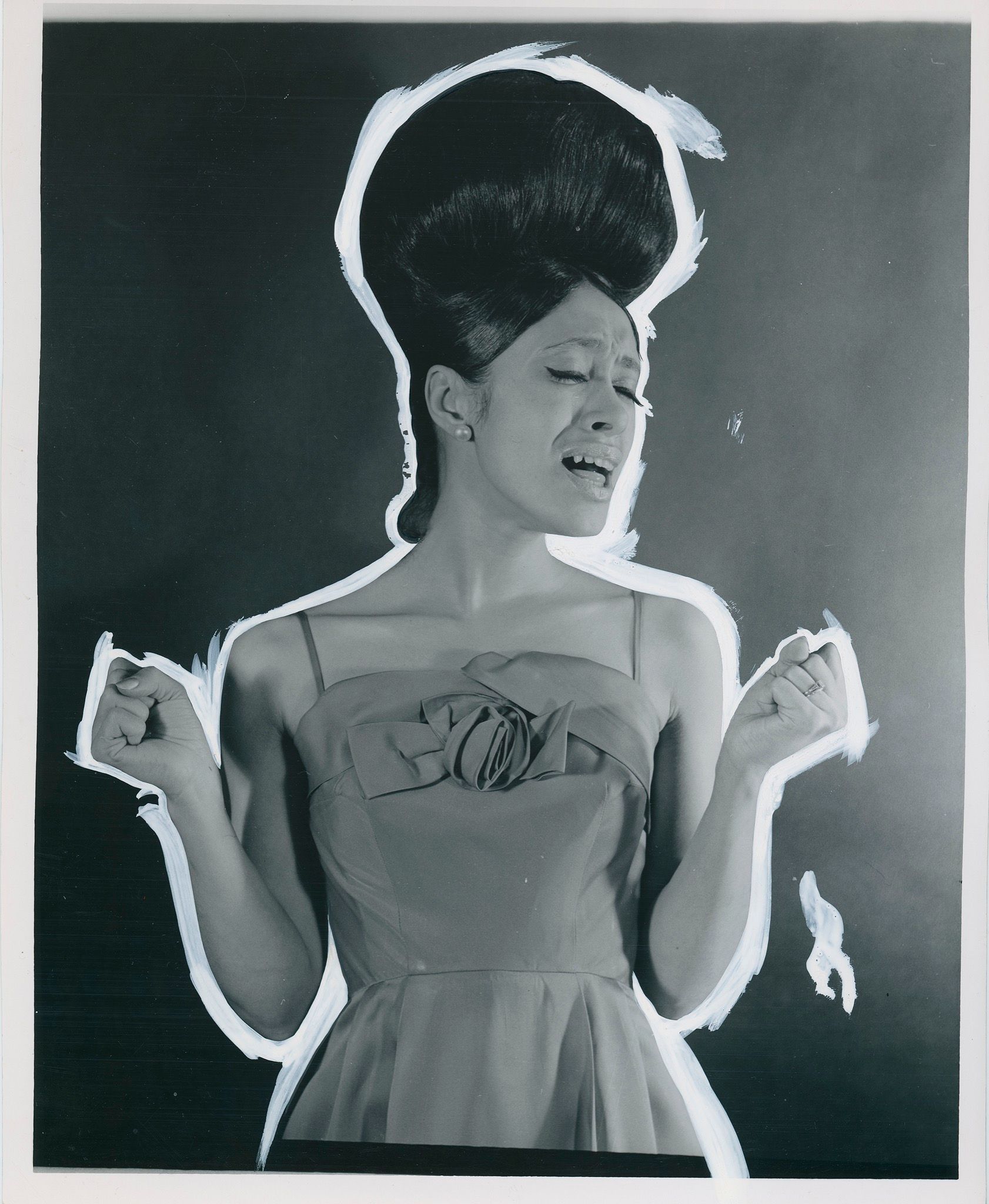

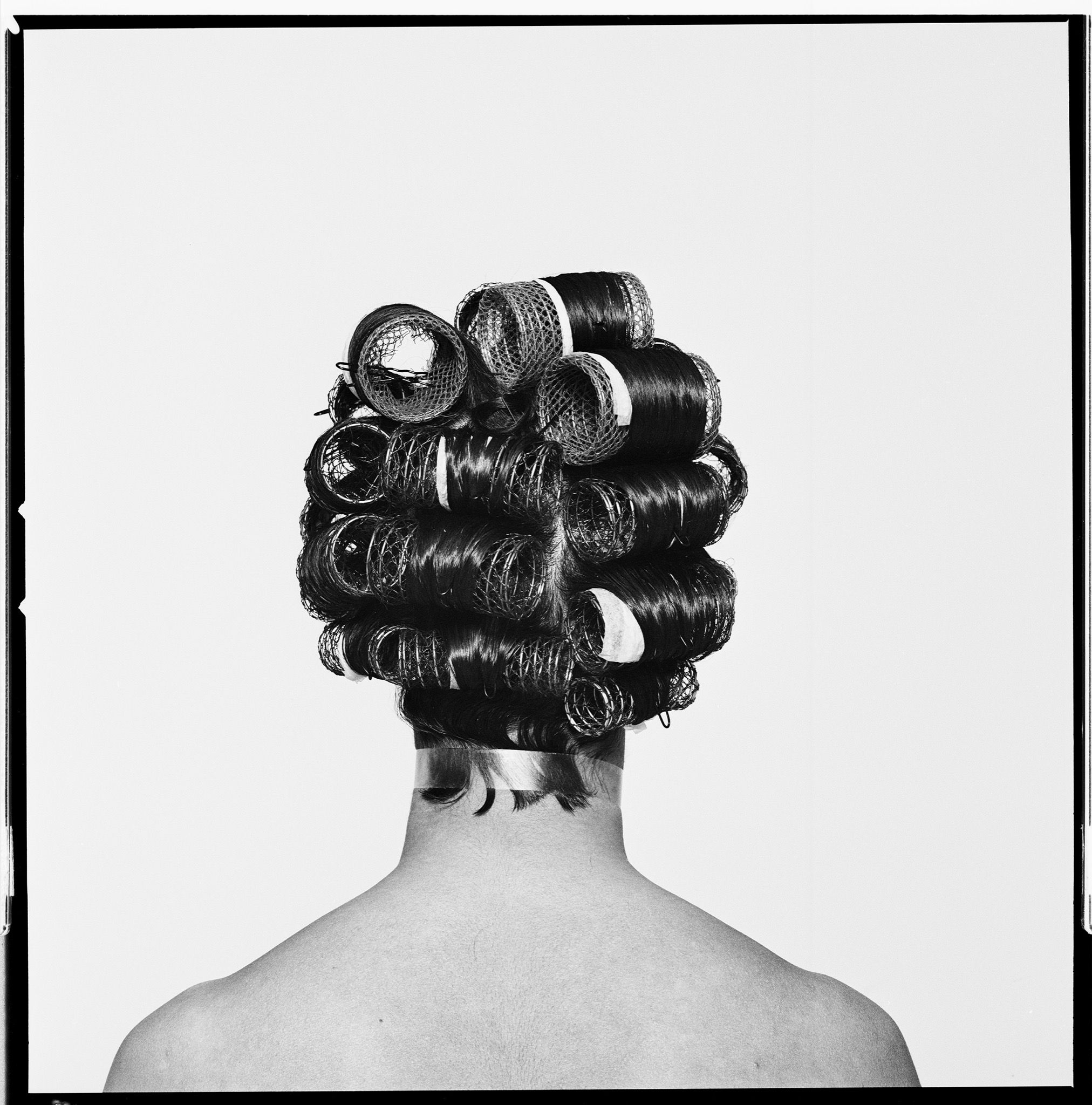

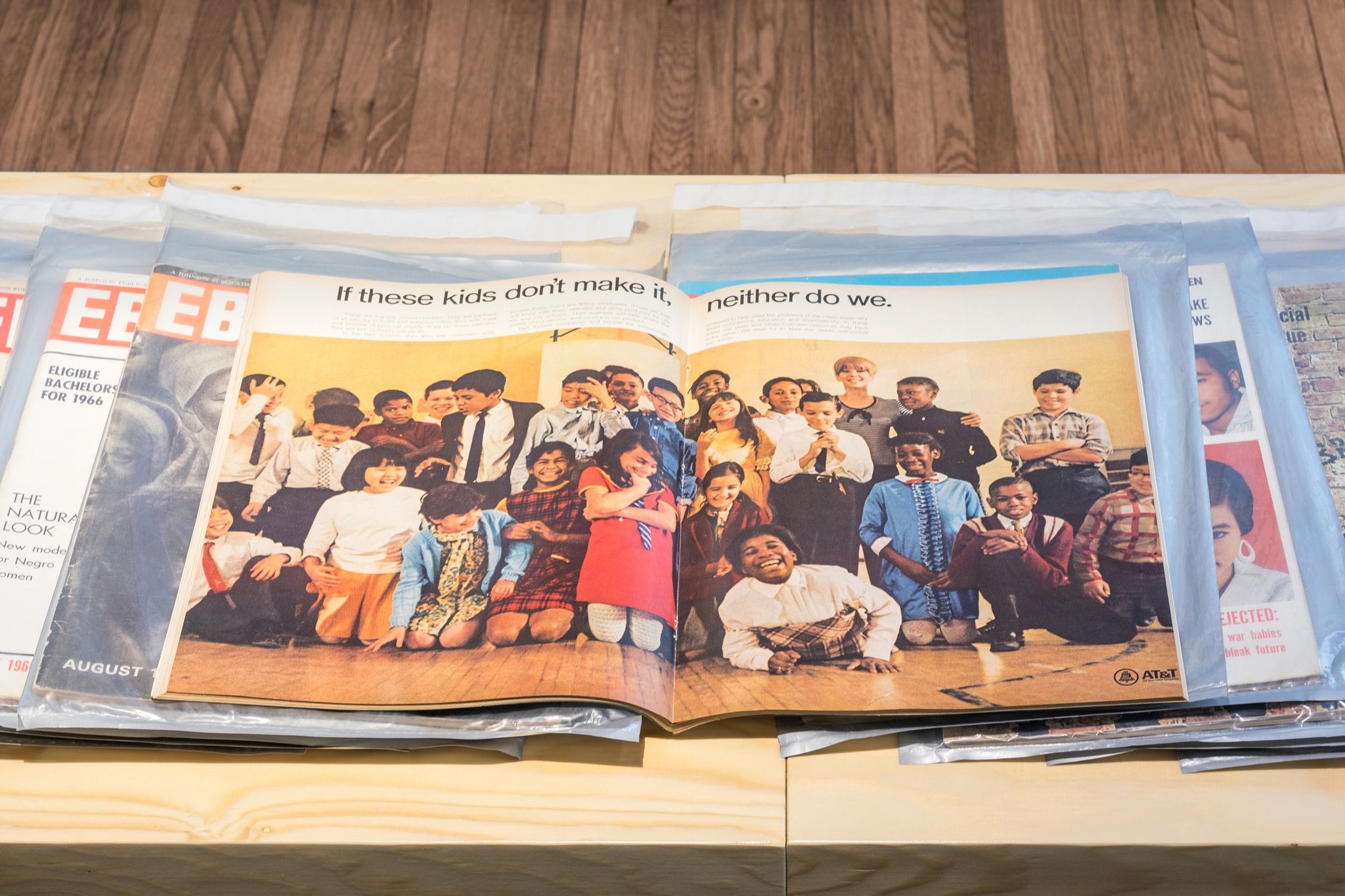

Conceived by Theaster Gates and debuted at the Fondazione Prada in Milan last year, “The Black Image Corporation” is an exhibition of photographs from holdings of Chicago’s Johnson Publishing Company, on show at Berlin’s Gropius Bau until July 28, 2019. It’s an archive of more than 4 million images that appeared in such publications as Ebony and Jet, and shaped “the aesthetic and cultural languages of contemporary African American identity.” Gates, a Chicago-based artist known for ambitious social practice projects influenced by his background in urban planning and city design, approached the project as a celebration and activation of the black image – in Milan, through photographs of women photographed by Moneta Sleet Jr. and Isaac Sutton – and of black entrepreneurship and legacy-making. Represented here through a selection of portraits of black female beauty and power, and exhibited such that viewers can actually touch the materials using white gloves, the Johnson Publishing archive offers, according to Gates’ curatorial statement, “small forays into the lives of everyday people” rarely seen outside the communities the images represent.

“Life exists” in the Johnson archive, Gates told me, just as it exists and should be honored in other places of black creativity. This is one current that runs through the cover dossier in the forthcoming 032c Issue #35, in which we imagine the creation of a house museum for the American writer James Baldwin (1924–87) at his former home in Saint-Paul-de-Vence, France. A continuation of the following interview appears in our print edition alongside original and recovered material from Baldwin himself and from those concerned with the preservation of his memory, and with the importance of the black material archive in global cultural history.

You’re exhibiting an archive that originated in the US, specifically in Chicago, at the Fondazione Prada’s Osservatorio, part of a historic shopping “galleria” in Milan. Does the European context change how you see the materials?

You know, I think this question goes straight to the heart of how one imagines themselves in the world. I know the images are black images. They are very black, and they’re from a black newspaper. But they are also women, and they’re also fashion house, they’re also family wealth – which meant autonomous thinking. It is reasonable that they have as much right to be here for as many reasons as they would in the offices of Johnson Publishing in Chicago. And that feels good, that the transcendental permission that these images have means I could curate a show of black images that feel for me as at home on the top floor of one of the oldest markets in the world as they might in a downtown Michigan Avenue office. That is the truth of the complexity of blackness.

And the sophistication of the images.

The technical skill in these images actually holds up alongside any image from the fifties, sixties, or seventies. They hold up alongside any Karl Lagerfeld – take your pick of seventies badasses. So the presentation platforms should be as aspirational as Eunice and John Johnson were. They were wearing Italian clothes. They were wearing Swiss shoes. They were wearing German wigs, you know? It’s just when a black body puts on an Italian dress, it looks like a black dress. These are the complexities of this archive: you could read as much Europeanism into these images as you could blackness, but one would have to know how to see whiteness alongside blackness.

The presentation in “The Black Image Corporation” is so material. You have to put on gloves. It’s tactile. Can you comment on the status of the black material archive, as opposed to the two-dimensional archive? Obviously in America, and worldwide, it’s very neglected.

When I was young, I went to a place called the National Great Blacks in Wax Museum, in Baltimore. It was one of two wax museums that tried to materialize the past, and you would literally walk through time, not unlike the National Museum of African American History and Culture in DC. There’s this idea that history museums are supposed to do a permanent installation which constitutes the history of a people. All history museums believe this is the way to share history. There’s one story, you keep it there for twenty years, and you don’t rotate it because it’s expensive to make. I remember when the Jewish Museum in London announced that they were rebuilding – they had these questions, like should it be primarily in Yiddish with translations to English? Are we making this for Jews? Are we making this for the world to understand the Jewish experience? And so those are the kinds of questions that I’m asking myself. Why would black things matter to others? And how do you make black things matter, when they’ve been neglected, or when they’ve just not mattered in the past? The problem is that we’ve just lost our specialized knowing of a certain kind of reactivation. We don’t have the skills anymore to keep things alive anymore. And because we don’t know how to keep things alive, it means they become even more disposable than their real use-value.

So the objects lose value, instead of accruing it as part of a special collection. In the upcoming issue of 032c is an interview with a sociologist called Luc Boltanski and his collaborator Arnaud Esquerre who have co-authored a book called Enrichment, which is partly about how objects gain value when they are collected – and how the people who collect them, of course, get richer.

Right. Here we have a black publishing company whose infrastructure didn’t know how to monetize its past. They were interested in legacy making. So in a way they slipped past monetizing their collections only thinking that they wanted their mother and father to be remembered in the most beautiful ways. So here I come, like, “Whoa, whoa, whoa, before you sell the four million images to some private collector, or before Getty gets it, or before Target gets it and just makes a bunch of posters of Little Richard – can I at least try to demonstrate what a kind of social enrichment might look like?”

It’s a museological, artistic approach, that is in fact not even art historical. I’m actually not interested in the person’s name, or where the thing was shot. I’m not trying to even offer that in this show necessarily. What I want is for people to be tantalized by the truth of the existence of black people. I want them to be overwhelmed by the gorgeousness and the compatibility of their lives. We don’t need any information for people to understand these images. Let me just show you what would happen if you were to take the past and make that a part of the Johnson Publishing living experience. The dresses shouldn’t be on mannequins. They should be on sisters. But that requires somebody who knows the Japanese kami – the spirit inside of a tree or a rock. If you can find some fucking spirit in a rock, you won’t bulldoze the rock. If you know that god lives in the dress, you would want the dress to live on a person so that god could live close to the person.

The work in “The Black Image Corporation” is particularly interesting because it’s very intimate, but it’s also documenting a professional environment – it is about an important publishing house.

Yes – the art world especially has an aversion to business. Or at least it tries to act like it does. But the truth is, certain artistic material forms can only emerge as the consequence of business. An example would be Richard Serra needed a shipyard in order to cast the rolled, steel pieces that he was doing in Germany. In the absence of the boating industry, one couldn’t make major modernist works. In order to exhume the black image from Johnson Publishing I had to license the right to those images. I had to hire a lawyer. I had to put my money down. I had to move a team of six scanners, administrators, into the Johnson office because they didn’t want their images to leave the space for security reasons and licensing reasons. I was a business. I was a parasitic business inside a dinosaur. And that in the house of blackness, you know? If no one’s willing to deal with the truth of my contracts, my negotiations, then that’s where my fucking genius is. And if you imagine that the intensity lives only in the final output of the thing, you’re wrong. I’m not even talking about process. I’m talking about procedure.

It’s like midwifery.

You’re damn right. That thing can’t come to exist unless I’m doing good business. So I decided that in the naming of the exhibition, I would just become the new Johnson Publishing Corporation for this moment – that is what I am. And since the name Johnson Publishing Corporation is not available to me, how close can I come so that I honor Linda Johnson Rice and Eunice and John, and give myself a new adjacency, being connected to Marcel Duchamp or Marcel Broodthaers, but wanting to move those practices forward? That’s the activation.

You’re inhabiting the archive.

Right? And it’s business. If I’m able to buy the entire archive, it may in fact change the course of my artistic practice. That’s the truth. If I’m given the archive, if I figure out the right negotiating tool so that my deal is as good as potentially the Gettys or Googles or the National Museum of African American History and Culture, I will do better than any of them. I will do better than any of them at activating, at giving life to those things, because I know God exists in those images. I know that.

Life itself exists in them, right?

Life exists.

Credits

- Text: Victoria Camblin

- :

- :