Where are the real investments? THEASTER GATES on JAMES BALDWIN

|Victoria Camblin

Conceived by Theaster Gates and at the Fondazione Prada in Milan, “The Black Image Corporation” was an exhibition of photographs from the holdings of Chicago’s Johnson Publishing Company – an archive of more than four million images that appeared in such publications as Ebony and Jet, and shaped “the aesthetic and cultural languages of contemporary African American identity.”

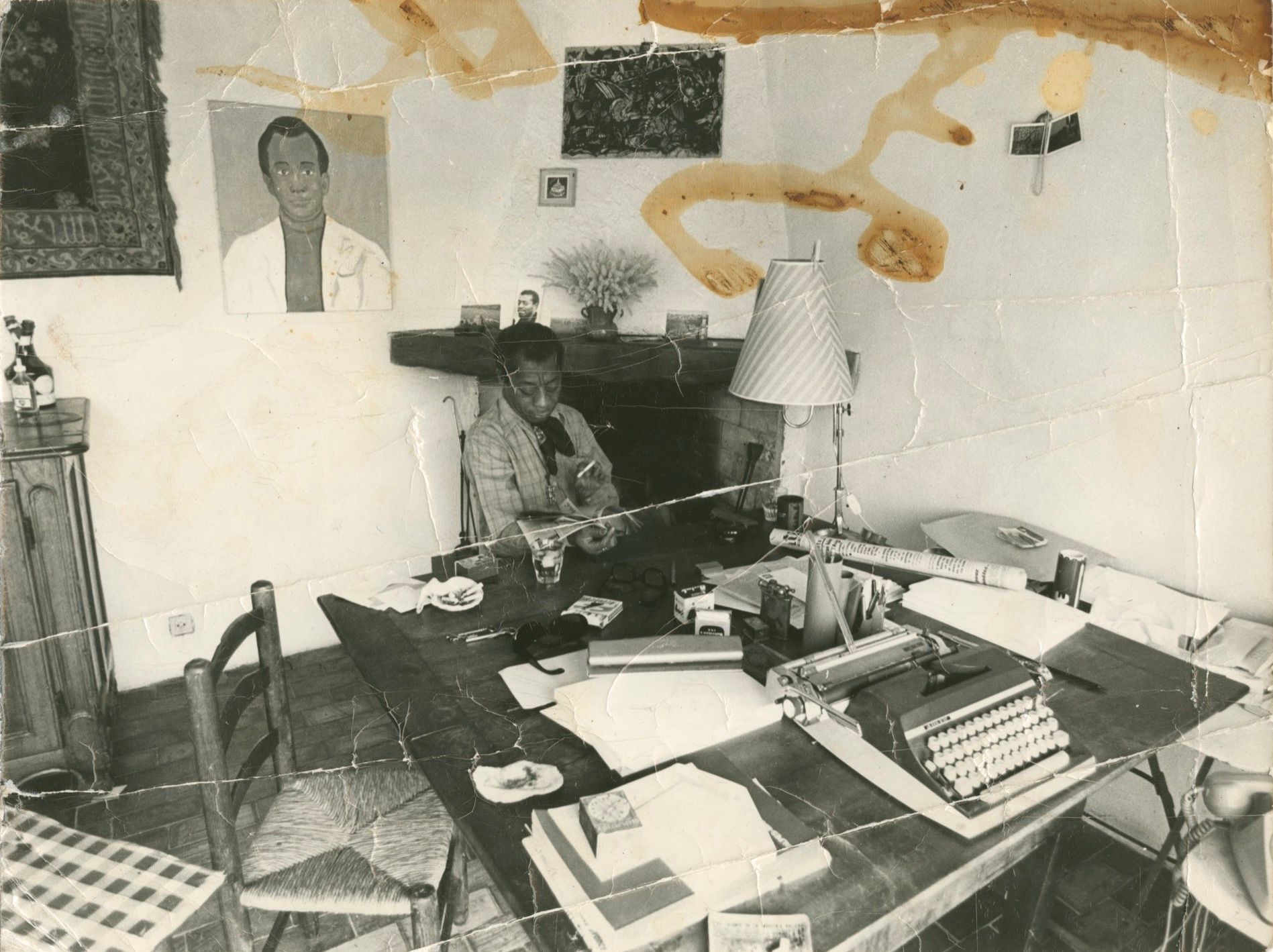

Gates, a Chicago-based artist known for ambitious social practice projects influenced by his background in urban planning and city design, approached the project as a celebration and activation of the Black image – in Milan, through photographs of women taken by Moneta Sleet Jr. and Isaac Sutton – and of Black entrepreneurship and legacy making. “Life exists” in this archive, he told us, just as it exists and should be honored globally, in spaces and materials of Black creativity. One such place on Gates’ radar is Baldwin’s home in Saint-Paul-de-Vence. The artist has considered the notion of the house museum before: in 2016, his “How To Build A House Museum” at the Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto, proposed an exploration of its many possible forms – as an architectural monument, as a site of freedom, and as a history with the potential to be activated, for example, through cultural and public programming. Chez Baldwin may no longer occupy its geographical home, but social and artistic engagement, Gates suggests, may allow the contents and spirit of Baldwin’s home, and others like it, to settle in lived experience.

You selected Raoul Peck’s I Am Not Your Negro, a documentary about James Baldwin, to screen as part of the film marathon accompanying your show at the Fondazione Prada, and the Baldwin text upon which that film is based was originally called Remember This House. You did an exhibition a couple of years ago in Toronto around house museums. James Baldwin’s house in the South of France is among countless homes of Black authors and artists that have not been memorialized. Libraries are buying the annotated manuscripts, but the domestic archive is ignored. Can you comment on this neglect of significant buildings and things?

When I was young, I went to a place called The National Great Blacks In Wax Museum in Baltimore. It was one of two wax museums that were history museums about the experience – that tried to materialize the past. And you would literally walk through time, not unlike the [National Museum for African American Art and Culture] in Washington, DC. There’s this idea that history museums are supposed to do a permanent installation that constitutes the history of a people. History museums believe that this is the way to share history. One story, you keep it there for 20 years, you don’t rotate it, because it’s expensive to make. I remember when the Jewish Museum in London announced that they were rebuilding, and they had these questions, like: “Should it be primarily in Yiddish, with translations to English? Are we making this for Jews? Are we making this for the world to understand the Jewish experience?” And so those are the kinds of questions that I’m asking myself when I start to think: “Why would Black things matter to others? And how do you make Black things matter when they’ve been neglected, or when they’ve just not mattered?” So I have some thoughts on this. Driving down the street in my neighborhood, we’ve got a Starbucks, we’ve got a Subway, we’ve got a laundromat, we’ve got a Domino’s Pizza, we’ve got a Walgreens, we’ve got a currency exchange – every mile has the same configuration. The problem is there’s no fucking urban imagination, there’s no platform-making imagination that would have someone say, “Oh, in addition to a Subway, we also need a center for the preservation of Black-owned houses.” If you can’t name the thing, it will not exist.

You need something that’s active in the present.

That center would gather a fund so that when a white person wants to move to a Black neighborhood, and there’s a fear of gentrification, the fund would be able to ensure that other Black people move to the neighborhood. The fund would manage value, so that if you bought it for 10,000, you could sell it for 11,000. But you can’t sell it for the imaginary value, the speculative value. In addition to the center for Black homes, we also need a storefront for Black local things. In Chicago, we have a place called the DuSable Museum [of African American History]. The DuSable had been a repository: when a person’s uncle died and was a general in the Second World War, they could give their uniforms to DuSable. And so they have uniforms, they have clothes, they’ve got musical instruments. It got to a point where DuSable couldn’t receive those things anymore. Nobody knew what to do with the things in the basement, the things in the attic! How do you activate them? If you’ve got a car that won’t start, and you’re not a mechanic, you get rid of the car. So the problem is that we’ve just lost our specialized knowing of a certain kind of reactivation. We don’t know how, we don’t have the skills anymore to keep things alive. And because we don’t know how to keep things alive, it means they become even more disposable than their real use value.

They have a negative value, instead of benefitting from a potential increase in value, over time, as a collection.

So we have a Black publishing company that didn’t know how to monetize its past. And here I come, like, “Whoa, whoa, before you sell the four million images to some private collection, or before Target gets it and just makes a bunch of posters of Little Richard, can I at least try to demonstrate what a kind of social enrichment might look like?” I want people to be tantalized by the truth of the existence of Black people. I want them to be overwhelmed by the gorgeousness and the compatibility of their lives with these people. We don’t need information for people to understand these images – let me just show you what would happen if you were to take the past and make that a part of the Johnson Publishing living experience. I will do better than the Getty or Google or the African American Museum at activating, at giving life to those things, because I know god exists in those images. The dresses shouldn’t be on mannequins. They should be on sisters. But that requires somebody who knows the Japanese kami – the spirit inside of a tree or a rock. If you know that god lives in the dress, you would want the dress to live on a person so that god could live close to the person. If you can find some fucking spirit in a rock, you won’t bulldoze the rock.

This is the story of Baldwin’s things too. What would you do with his house? How would you activate and energize those materials?

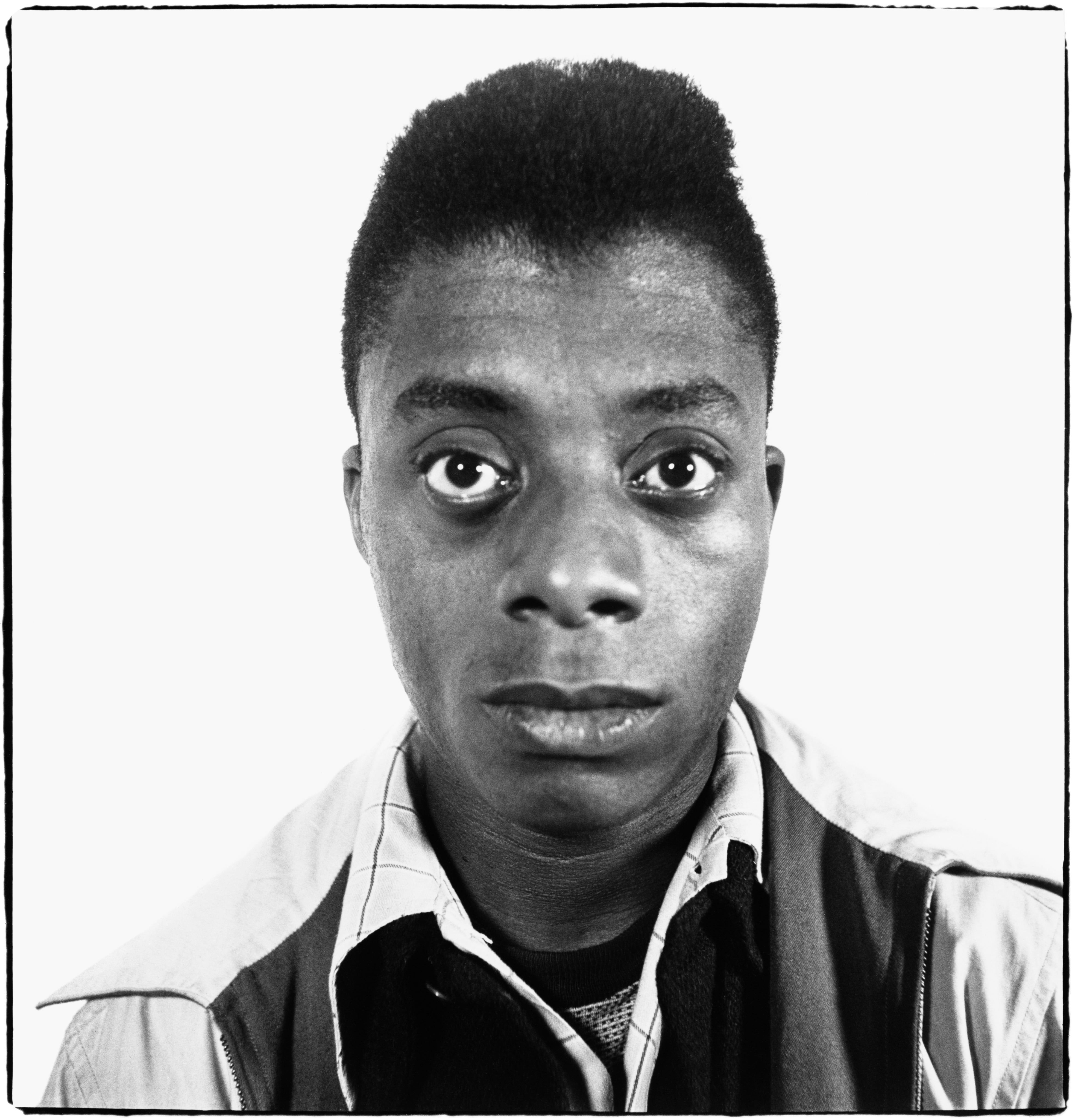

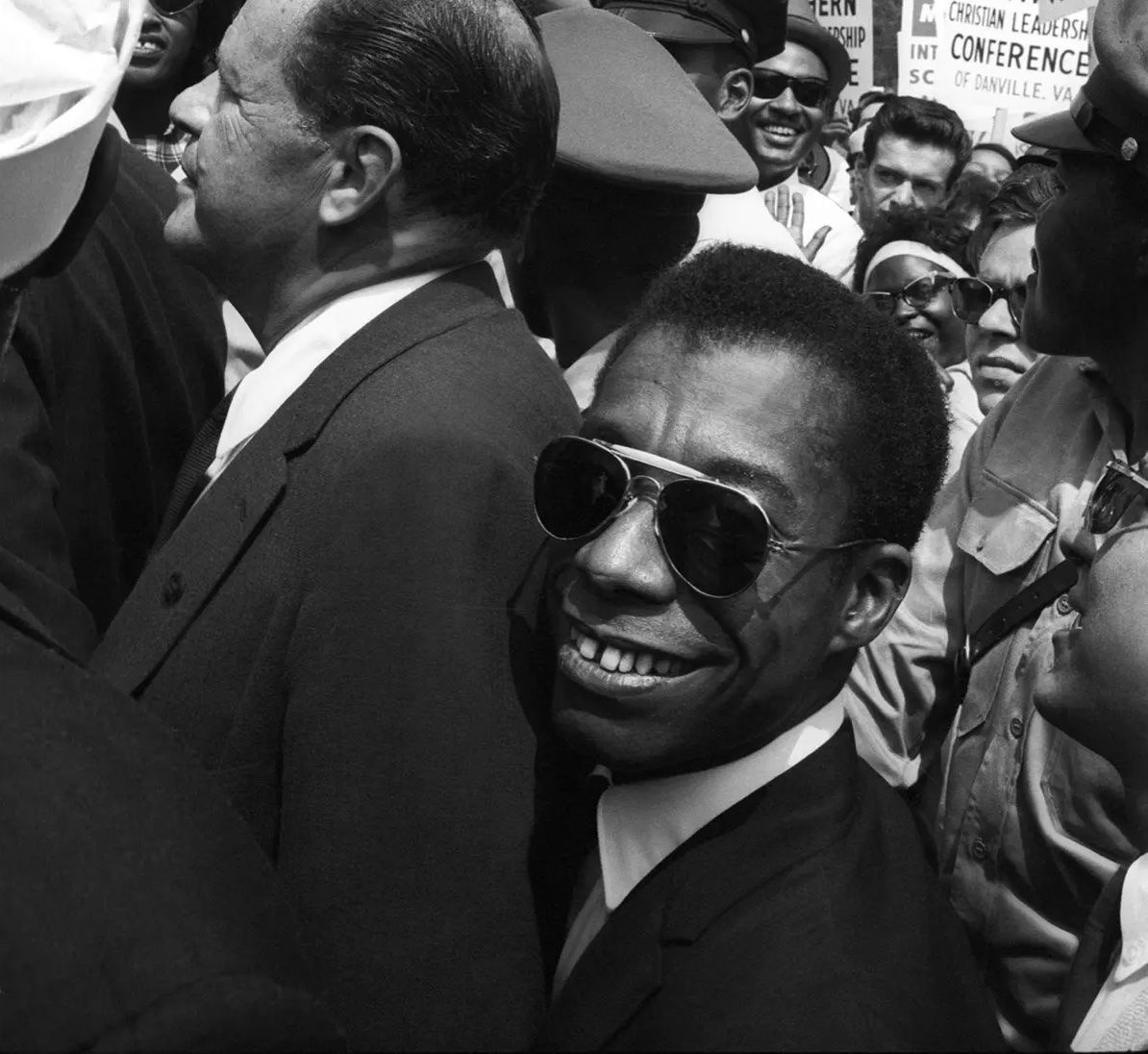

Two years ago, in 2016, I was given the Légion d’Honneur. And we had a big celebration at [the Stony Island] Arts Bank, at my building. The French ambassador was there, and one of the cultural attachés said, “What would you like to do in Paris, or in France?” And I said, “I’d like to do James Baldwin.” The house was still standing at that point, but it was already bought. And what I realized was that there was a relationship between my cultural status, being adjacent to political and spatial bureaucratic power, and this particular topic, which I was also clearly adjacent to. That [relationship] was creating a kind of perfect triangle of potency or potential. That’s how my brain works, kind of – I’m interested in the sums of things, in how through procedure great things are possible, you know? I like that. I could tell immediately that there was interest in my interest – and that also there was a kind of impossibility. But Baldwin represents a generation of Black makers in France. He may be one of the more known because he had a few books published and won some awards – but in fact, he was probably not the most known, especially in his day, right? He was a Black dude trying to get writing and then being introduced to publishing houses and then becoming great outside and inside of the country. And then the part that could be interesting: “What would the French want the Baldwin legacy to look like?” Right? So in the absence of the Baldwin country home, the only people who are willing to make those kinds of moves would be a restauranteur who would open a place called Baldwin’s –

Pronounced Baldween’s.

Baldween! And they would buy all the ephemera that they’ve collected and put it up on the fucking walls, and then they would monetize it. It’s enrichment!

Speaking of bureaucratic or diplomatic procedure, Saint-Paul-de-Vence itself could have monetized that house. France is full of towns that have built a tourist industry because someone like Van Gogh summered there. Baldwin was in that house for decades.

Well that has something to do with what some might call racism, you know? We don’t actually honor all things equally. And we don’t know why the town didn’t pick up on Baldwin more quickly. But it could have been, “Yeah, he’s just a Black writer.” And, you know, in fact, it’s just for entertainment. You can claim it as, “Oh, I want to help the lives.” I think about this even with people collecting. When you buy something from me, you know that a year from now it will have more value. So I’m doing you as much a favor as you are me. You ain’t helped me yet by buying a thing today you can still get for 10,000 dollars – tomorrow you can sell it for 20. You’re not helping me. So then the question is, “Where are the real investments?” So I think that part of what I may do over the next year or two is kind of ask: “What is this little medal? What can we do with this?”

Credits

- Text: Victoria Camblin

- Photograph: Courtesy of NMAAHC; photographer unknown