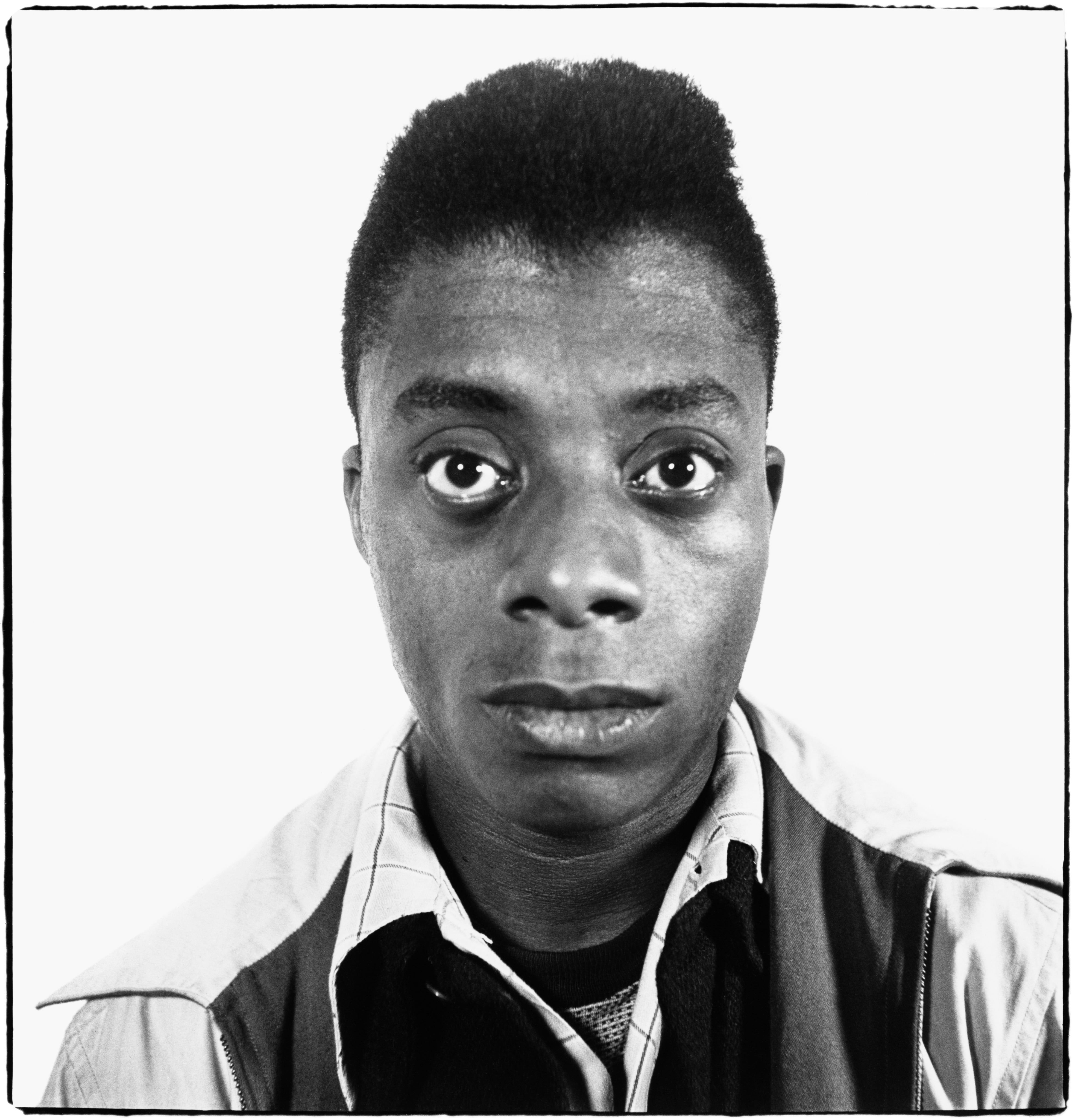

“I live a hope despite my knowing better”: JAMES BALDWIN in Conversation With FRITZ J. RADDATZ (1978)

|FRITZ RADDATZ

“People are trapped in history and history is trapped in them.” — James Baldwin.

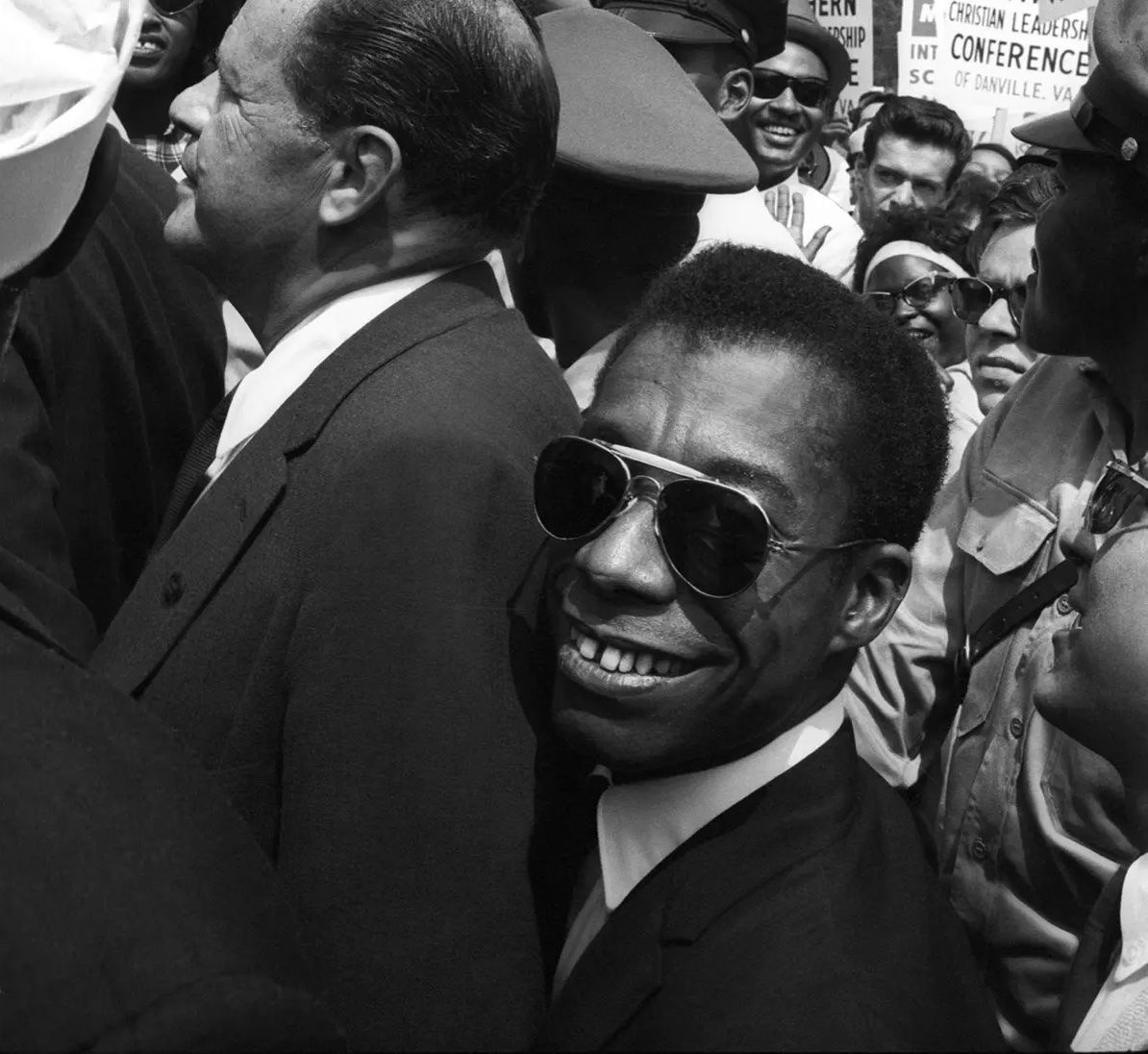

On the occasion of the 100th birthday of American writer and civil rights activist James Baldwin, who passed away in 1987, we’re republishing our 2019 dossier on the novelists, consisting of a conversation between him and Fritz J. Raddatz, Hilton Als on Baldwin’s body, Baldwin’s provencal home, and a text by Theaster Gates on the writer.

Whatever the exact circumstances of James Baldwin’s first encounter with his friend Fritz Raddatz were, they must have been fabulous – a chic party, perhaps, somewhere in a European capital. Raddatz was Baldwin’s German language editor at Rowohlt Verlag, but he had other vital jobs. He was, for example, an intercessor at dinner parties. In his diaries, Raddatz refers to one shindig in the mid-1960s as “the night of [Austrian poet Ingeborg] Bachmann’s useless infatuation with gay Baldwin, who begged me to get him away from her.”

The same evening, German writer Uwe Johnson had a serious argument with Baldwin, which got away from everyone and culminated with Johnson throwing a punch at publisher Henrich Rowohlt’s wife after she came to Baldwin’s defense. In 1967, Raddatz also assisted Baldwin in an attempt to get Tony Maynard, the writer’s friend and former secretary, out of a Hamburg prison – an ordeal that would influence Baldwin’s depictions of false accusation and incarceration in If Beale Street Could Talk, and cement his friendship with Raddatz.

Born in Berlin in 1931, Raddatz had relied on food delivered by African American GIs after the death of his parents, and to Baldwin he was an “anti-Nazi German who has the scars to prove it.” Bisexual himself, and an intellectual rogue, Raddatz told 032c in a 2012 interview: “Throughout my life, I have always had to go. I was always thrown out of everywhere.” His sympathies were with Maynard. According to prison policy, only lawyers and family were allowed to visit; Raddatz and Baldwin were neither, but the editor got them in anyway. He even arranged a private room, a “place where we could smoke and talk.”

Baldwin had been locked up himself once, imprisoned in Paris for eight days after receiving stolen hotel sheets, and was terrified for Maynard. He recalled of one anxious visit: “And there we waited, for quite some time. Another functionary appeared, explaining that Tony was not in his cell and could not be seen that night. My German editor [Raddatz], smelling a rat – I didn’t, yet, and the lawyer seemed bewildered – pointed out that Tony, in his cell or not, was, nevertheless, somewhere in the prison, and that we were perfectly prepared to wait in this room until morning, or for weeks if it came to that: that we would not, in short, leave until we saw Tony.”

When Maynard arrived, he had been badly beaten, his face swollen and ribs bruised. Baldwin realized that a mistake had been made: not only was his friend a pulpy mess, but his visitors had been allowed to see him that way. “No one would have taken my word for this beating, or our lawyer’s word,” Baldwin wrote. “But Fritz knows what it means to be beaten in prison. And he, therefore, not only alerted the German press, but, armed with the weight of one of the most powerful German publishing houses, sued the German state.”

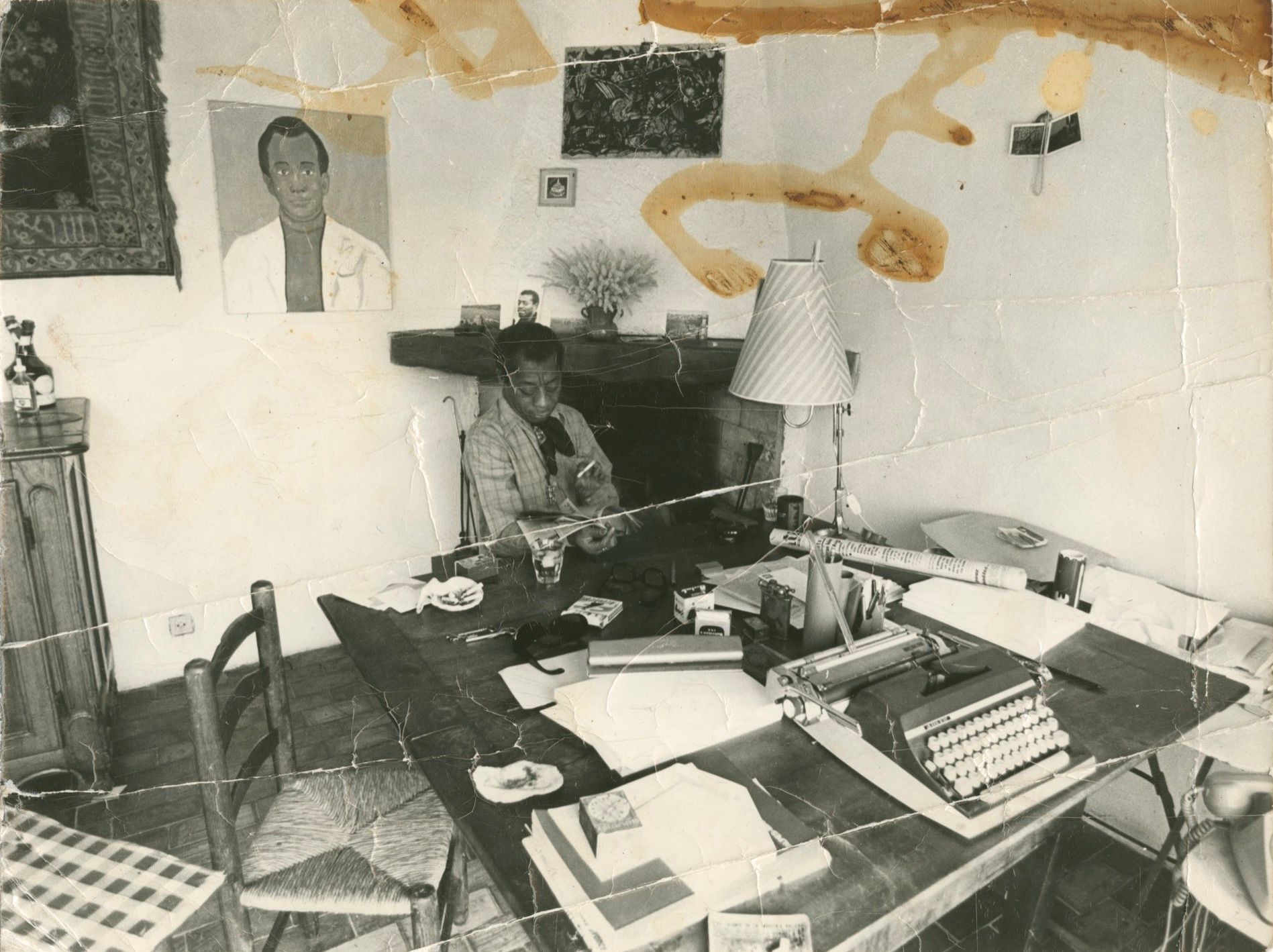

In 1978, more than a decade after Hamburg, Raddatz conducted the following interview for Die Zeit at Baldwin’s home in Saint-Paul-de-Vence.

FRITZ RADDATZ: You’re definitely going back to America – that’s a “historic” decision after spending 25 years mostly in European exile. Why?

JAMES BALDWIN: As unbelievable as it may sound, I can’t exactly say why. I smell water like a horse smells water – I sense something, I feel something. Until now, this instinct never failed me. You know, when I wrote The Fire Next Time, people were dismissing it as a form of black prophecy. A year later, America’s cities were burning. But now there are no cities burning. There is no militant or even revolutionary black movement in the US. There’s hardly one thought-provoking voice, not even that of James Baldwin. There’s a lot to say on that subject. The ugliest part first: because they were all murdered. Ask me about the Black Panthers, about Black Power. Ask me, and I’ll tell it how it is. They were killed, they were slain, like rats on the street, in their houses, in their beds.

But Jimmy –

No, don’t interrupt me. This story is far too merciless for that – and I’ve to tell you about it if we’re having this conversation. Since they could buy us as slaves on the auction block, the whites in this country merely used us and threw us away, as they do today, with their cars and their Kleenex tissues. We were and we are merchandise. Race struggle is class struggle. Every un- employment rate proves that, even today in 1978. They humiliated us. They destroyed our identity, and when we began to discover a new one –

Black is beautiful.

Call it as you wish. But there was a time when black school children, when you showed them photographs and asked them how and who they wanted to be in the future, finally began to abandon the habit of automatically pointing to the image of a white person. This was the time when I asked: “Why of all things should I want to become like a Kennedy or even like a Nixon? What do they have to do with me? I would rather kill myself with the help of a few bottles of Scotch, 27 sleeping pills, or a razor than wish to become one of them!” Then, in reaction to that, the whites began to use their weapons. They no longer destroyed merely our souls, our sense of self-respect; they killed us physically.

But Jimmy, there are no concentration camps in America.

You especially, as an anti-Nazi, shouldn’t talk like that. The whole city of New York is a concentration camp, a ghetto. There is none of us that wasn’t in danger, none of us that doesn’t have one slain in his family, and there is almost no family without at least one person who became a criminal precisely because of that. I myself know how my fear made me feel that tingling lust to kill often enough. The glorification of massacre is even part of American folklore. It’s stylized to a noble and heroic legend, and thus accepted and imitated.

As little as history repeats itself, as little does it stand still. You are deducing from the past: to you, the individual James Baldwin, nothing is happening today. You have overcome the story of blood and terror.

That’s a noteworthy number of mistakes in one sentence, Fritz. What happened to me – me – a thousand years ago is happening to me now. Two endings of the same story: my name is Baldwin, I bear the name of a white man; do I have to explain to you of all people what that means? This man was once my owner! The other ending: one of my earliest memories is the day when I – I was six – was almost beaten to death by two white police officers. Who was speaking then, myself or my history? The police or their history? How can I view history as something of the past when two grown men are treating a child in such a criminal way for the sole reason that the child’s skin color is black, a child who doesn’t even know what it means to be black? I’ve known it since that day. This country of America, my compatriots – they are my murderers.

Are you returning to your murderers voluntarily? Are you Mr. Samuel Goldstein who can’t decide to leave his fur store in Berlin in 1936?

I’m going to tell you something: it’s much, much more complex. I don’t want to minimize the agony that the Jews had to suffer from the Germans in your country. I only want to quote an answer, a phrase that I once used in a similar conversation with your Jewish colleague Jakov Lind. He was telling me about his illegal journey through Nazi Germany by train. And I said to him: I couldn’t have done it. Do you understand? A blonde wig would not have helped me. That is the first part, the individual one. You have to add that, when you say that I’m not in danger today, that you can’t make any generalizations from the situation of a relatively well-known artist. It doesn’t depend on me as an individual; I can only be a membrane, a voice. And even a James Baldwin, a Harry Belafonte, a Sammy Davis Jr., even they are affected. Do you remember how they let Billie Holiday die, exactly those same whites who applauded her earlier, even when she sang “Strange Fruit”? You sure know the millionaire Sammy Davis’ terrible phrase: “Being a star has made it possible for me to get insulted in places where the average Negro could never hope to go and get insulted. Maybe by 1999 I’ll even be able to rent an apartment in one of those buildings where they throw parties in my honor.”

I know his book, I know your books – I know, I know that you’re absolutely right. What I wanted to get at: all your works are pervaded – are sustained by a vision, a sermon for love, for forgiveness. I don’t sense any vengefulness, any violence. I find the prophecy of love at times even going too far – it seems sentimental. Sentimentality is the opposite of emotion. It is usually the disclosure of a fracture. How do you reconcile your almost hateful verdict about your country with this kind of sermon?

This, I’m sorry, again asks for an answer with multiple twists. No, I’m neither a sentimentalist nor a romantic. I’m not at home in America, and I will never be, which means that I will never be at home, not anywhere in the world. But, as strange as it may sound: I love this country. When I came to France as a young man, I woke up in the nights in agony, screaming from terrible dreams – it must have been the horror of being uprooted one more time. It feels like being born again. Or like drowning, like disappearing into nothingness. I don’t belong to Africa; Africa is utterly foreign to me. I don’t belong to Chartres; even if I touch this culture, I touch it the way a sculpture by Giacometti does. But it was made by him. I’m the despised bastard of the West. And as long as people – people, that is: all blacks, all whites – don’t accept that we have the same right to love, as long as they continue to denounce us and are not willing to see the mountain of rubble, the pile of corpses, as long as that is the case, all of us will be murdered, in different ways: burned, hanged, drowned, castrated – and many are already dead when they’re still alive. You’re right: I am a prophet and a preacher.

Is this contradiction the strange contradiction that characterizes many of your books? On the one hand, there is this endless chain of growing unhappiness – black self-hatred, the experience of being merchandise, of being a sexual object – and then the impossibility of continuing to love. For example, your character Rufus in Another Country, who dies from a kind of reinjection of the white mania, who becomes a kind of anti-white racist and who – instead of experiencing happiness from the love of a white woman – feels corroded by it. A “criminal out of lost identity.” On the other hand – if I may stay with the example of this character – when Rufus is dead, his white friend Vivaldo thinks, “Could I have saved him if I had reached out my hand a tiny little bit back then and held him?”

Hope and its permanent disappointment, that is no contradiction – except if you wish to call life a permanent contradiction.

But almost all your characters drift apart from each other even while they are still in love. Their embraces are rather entanglements reaching for a clinch that does not lead to closeness, but only to an ephemeral avoidance of blows.

This is what the white American civilization did with, did to, humans. You once told me the story of a white German military officer who entered Picasso’s Parisian studio in 1942, saw Guernica, and asked, “Did you make this?” Picasso answered, “No, you did!” This is the answer that I must return to you. And even today, when we had lunch and I was asking about the smear campaign against the intellectuals in Germany, about Grass and Böll, you told me about “everyday fascism,” about Brecht’s play The Jewish Wife, whose “Aryan” husband sends her to friends in Amsterdam in mid-summer 1935 “for four weeks only,” and who assists her getting into her fur coat. This is also what I have to return to you as an answer. Do you think this comes to a halt in front of any, even the most intimate, area of life? I could write another – thousands of one-act plays called The White Man. When I was very young, a friend took me home to his parents. He had told them about me. They wanted to meet me. When I entered the room, their jaws dropped – he had forgotten to tell them that I’m a Negro. My fur is my skin. It’s black.

Does that explain why sexuality plays such an important role in your books?

It doesn’t play a more important role in my books than in the lives of people. I don’t write sex books. There is no obscenity in my works. At least if you accept my definition of obscenity. To me, the neutron bomb is obscene – but not a penis. To me, the phrase “I’m shooting” is obscene when it means “I’m coming” – not the word “fucking.” To me, it’s obscene that, to a white man, I’m a sexual organ to which – unfortunately – a human being is attached.

You’re exaggerating.

I’m not exaggerating at all. By chance, there is a book by the playwright LeRoi Jones lying on the table. May I read a passage to you? “But the mutilation of the sex organs occurs again and again during lynchings. It is not enough that the black man has been socially demanned; the actual rite must go on too. And the act of cutting off a man’s sex organs and stuffing them in his mouth should be analyzed as closely and deeply as possible. By removing the black man’s organs, his manness, the white man removes the threat of the black man asserting that manness, by taking the white man’s most prized possession. Trying to strangle a man with his own sex organs, his own manhood: that is what white America has always tried to do to the black man – make him swallow his hatred.” Am I still exaggerating?

How do you want to write with this bitterness? You’re currently working on a novel – can you write a book with such bile, with hatred?

It’s neither bitterness nor hatred, especially not a personal one. The largest part of my life is already lying behind me, and I could grow old as a kind of “elder statesman” here on the Côte d’Azur. But it’s a kind of schizophrenia when I don’t want to lose hope, when I want to be able, at least, to give hope to young people. When I once had a similar conversation with Margaret Mead, she used an image that I memorized for its horrible intensity: when a snake with two heads divides itself above or below its stomach, then it knows if it is one individual or not. If it has two stomachs, one head will try to eat up the other. I’m a snake with two heads, but one stomach. I’m an American Negro writer – which means that I live a hope despite my knowing better. If I stayed away, I’d really soon stop writing. You called me a preacher – you may call me a missionary. A black missionary for the white heathens in America. What’s happening in this country is unacceptable for me. And if it perishes in the flames – this country is bad enough. I’ll disappear with it, but I won’t accept it.

Credits

- Interview: FRITZ RADDATZ

- Translation: Gianna Zocco