The Real Capital of Fashion Isn’t Paris, It’s Hollywood: Emanuele Coccia

|SHANE ANDERSON

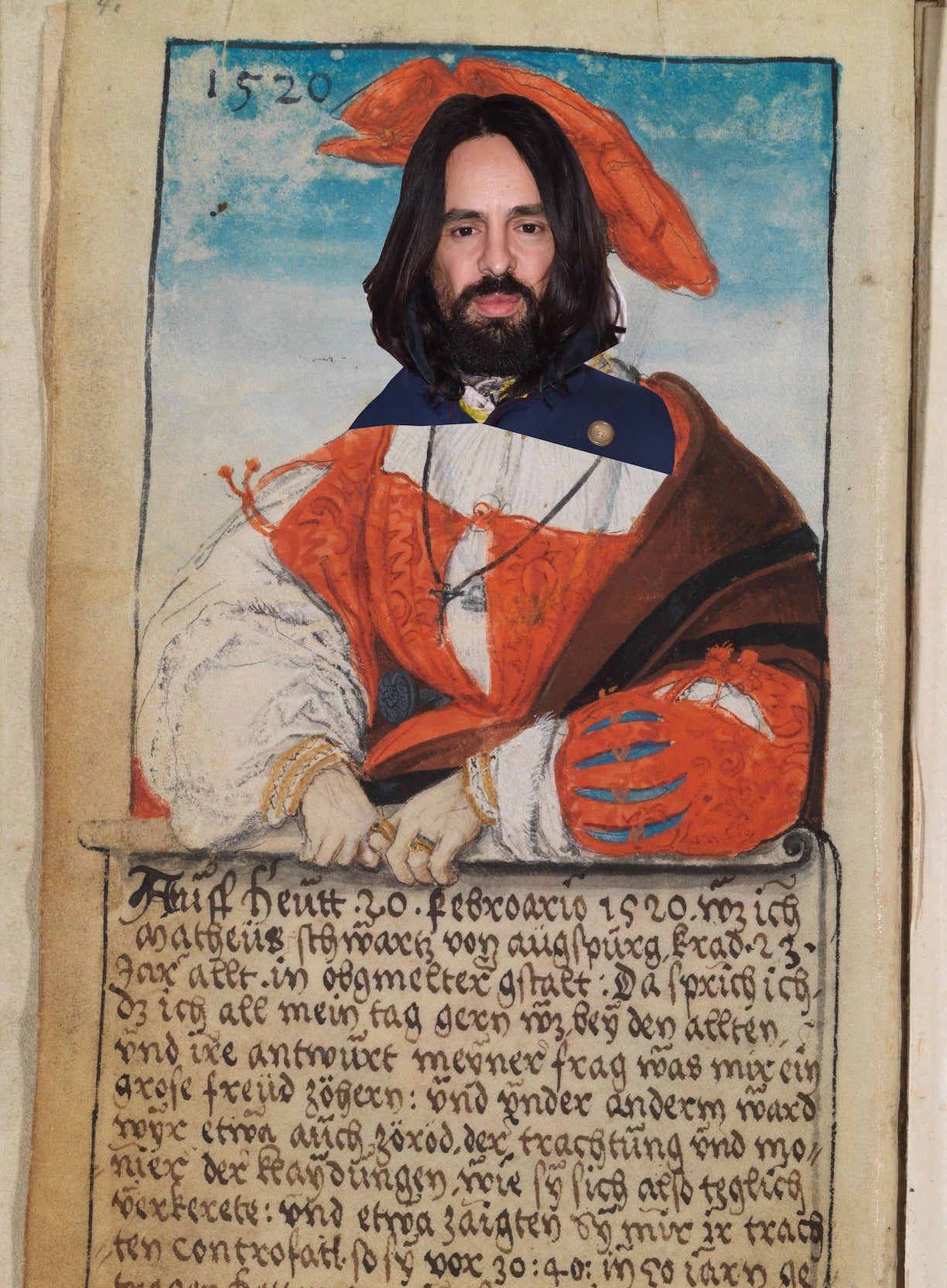

Clothes are like homes according to philosopher Emanuele Coccia. They’re both repositories for our dreams and are much more than material alone. Having developed his philosophy of homes in the book Philosophy of the Home (first published in Italian in 2021), Coccia has also written the book The Life of Forms (first published in Italian in 2024) with Valentino’s creative director Alessandro Michele, where they developed the intersections between fashion and philosophy through a series of provocative theses.

An associate professor at Paris’s École des Hautes Études en Sciences Sociales, Coccia has not limited himself to these, however. Having written books on a variety of subjects, Coccia is also a columnist at the French daily Libération and has collaborated with design studio Formafantasma, photographer Viviane Sassen, and others. Together with Olivier Saillard, Coccia recently co-curated the exhibition “Fashionlands: Clothes Beyond Borders” at the ITS Arcademy Museum of Art in Fashion in Trieste that opened during the annual ITS Contest. After its opening, Shane Anderson spoke to him from home to home about the exhibition, the intersections of democracy and fashion, and why it can reimagine time better than any other medium.

Installation view “Fashionlands: Clothes Beyond Borders” at the ITS Arcademy Museum of Art in Fashion in Trieste

SHANE ANDERSON: You’ve written books about plants, mysteries, advertisement, and many other subjects. Recently, you’ve also turned your eye to fashion. All of which are not principally understood as themes of philosophy. What’s your interest here? To lift unturned stones and see whether philosophy is growing there?

EMANUELE COCCIA: That’s not the first trigger of why I work on anything. Instead, it’s about the passions I pass through. It’s about encounters. And I mean, philosophy isn’t a specific knowledge defined by an object or a method or way of expressing itself. If you were look at the set of books that have been baptized “philosophical books,” they don’t have a common object. Marx wrote about the economy, Aristotle about biology, and Plato about love. They don’t share a common rhetorical register either. Some wrote poems, others scientific treatises, and still others novels. It’s not like in other disciplines. The only commonality is expressed by the name philosophy, which is about knowledge that comes from passion, from love. Philosophy is an intensity that arises when someone is taken hostage by their own questions. And so, maybe there is a common thread in my philosophy. All the topics are about how life takes form.

SA: The concept of habitability seems very important for your work.

EC: Totally, but only if we understand it in the sense of availability, of an active process transforming the world into something where life becomes possible—which isn’t a given. We used to think that the world is habitable in itself but that’s not the case. Every living being has to radically transform the space around it to make such space its home.

SA: You’ve written about homes, too. Another one of your passions?

EC: That book is in part the consequence of me moving almost 40 times in my life, if not more. When you move a lot, you really understand what a home is. It’s not just walls and a roof. It’s a set of objects, people, atmospheres, and events that you want to bring with you, even to the other side of the ocean. The home is sort of a collection of things you cannot live without. It’s a little world, which makes, as you suggested, the world habitable for you. But it’s also an embodiment of your happiness. You need to come back to this collection of objects and people every night because this is what makes you happy. This means that happiness is not just a set of feelings or emotions or something that exists in your consciousness or your soul. It’s a part of the world. This is a sort of cosmological experiment. Each house, each home, is a cosmic transformation of the world that allows the world to become the space and form of your happiness. So, homes are much more moral intensities than spaces. That’s why architecture should be a science of happiness and not a science of space or geometry.

SA: At one point, you also link the home to fashion.

EC: Yes, because garments are, in a way, the shrinking of your house to the size of your body. You can also say this the other way around. A home is a garment that you make larger than just your body. Clothes are also the only domestic objects we bring outside our domestic space. When you look at someone dressed in a particular way, it is as if you were in their living room.

SA: Yes, but there are some clothes I only wear in my home. I don’t leave the house in my pajamas—and I don’t wear them when I cook either.

EC: There may be some clothes you only wear inside but for most things you wear them both inside and outside. And the inside is becoming outside. Through the digital revolution with Zoom or other conference call services, for instance, public space is no longer on the streets mainly. The public space has become the domestic space. We can get in contact with other people through WhatsApp or Instagram or whatever from home to home without passing through the city. I mean, you’re at home right now and I’m at home too. There’s now a construction of public domestic space, which is quite contradictory, and it has transformed our idea of public, of gathering, of being with people. This is why I think domestic spaces are important to understand how we live together beyond the classical shapes of traditional families. With WhatsApp, you are literally cohabitating with people living on another continent. It’s as if the form of the house has become larger and becomes autonomous from a purely geographical or geometrical inscription in space.

SA: In your introduction to the exhibition catalogue Fashionlands: Clothes Beyond Borders, you write that fashion is the only art form where space is made up of time. How does that work?

EC: The idea was very simple. Fashion is the only art where you can imitate the past. You can make a dress or a collection from the 1940s. You cannot do that with other arts. You cannot paint like in the 40s. You cannot construct buildings from the past—or, you can, but it’s very kitsch when you resuscitate the past. But fashion does exactly that. Alessandro [Michele] was the first to say that fashion does not produce a distance to the past. Even though the point of fashion is to produce something new or contemporary, it has an open relationship to the past. What’s interesting is that, whenever you use something from the past in fashion, you liberate it from its pastness. Suddenly, the form is embodied as are a set of habits that define that past. They can live again. That’s a free relationship with time that I think is very specific to fashion in comparison to, say, architecture. Neo-Gothic architecture was not about literally resuscitating life forms from the past. It was just a decorative element.

SA: What about music? It also has a free relationship to the past, right?

EC: Yes, but it’s more about activating previous kinds of music. It’s more of a reflection on the formal aspects of what came before. It’s different in fashion. When Yves Saint Laurent made a collection in 1971, the idea was not to just take the silhouettes or forms from the 40s, but rather to resuscitate the sense of empowerment that women had at the time while the men were at war and women ruled the urban space.

SA: It was more of a political statement that sought to reactivate this previous time.

EC: And it caused a major scandal.

SA: How did you become interested in fashion?

EC: There are several reasons. Some are biographical. My family has two branches: the one that works in fashion and the one that tried and failed. I come from the latter. And this branch raised several generations with spite towards fashion. But when I was 20, I had the chance to see the other branch and found it interesting—my family telling me it was evil on earth produced the opposite attitude, of course. And then, when I came to Paris the first time, I became close friends with Azzedine Alaïa, an incredible, talented, and important designer who died some years ago. I also became friends with Carla Sozzani, who has played a major role in fashion over the past 40 years. Through them, I came in contact with other fashion designers.

Installation view “Fashionlands: Clothes Beyond Borders” at the ITS Arcademy Museum of Art in Fashion in Trieste

Then, there are reasons that even if personal are also theoretical. No other artwork or performance makes me feel as strongly as when I see a good collection on the catwalk. It’s like watching a walking Picasso. It’s like the artwork is animate. And then, from a theoretical perspective, what I find interesting about fashion is that we’re accustomed to think of identity as being based purely on immaterial elements or consciousness, beliefs, and ideas. But then fashion comes and puts yellow or a peculiar form on a body and suddenly this person becomes someone else. Identity is then something that is sensitive to color, form, size, and so on. It can be changed, manipulated, and not just something present in bodies or egos. You can change your identity every day. That’s quite interesting from a theoretical point of view. And politically, too. There’s a promise of autonomy and self-liberation, and I think that’s why fashion also occupies a very important role in Western democracies. Without fashion, democracy would be purely formal. It would be empty. You’d be able to vote but you wouldn’t be free to make yourself anew every day. Fashion allows you to follow your deepest desires or instincts or ideas.

SA: That’s a surprising reversal. I would have thought that democracy makes fashion possible. Totalitarian regimes often impose restrictions on clothes, right?

EC: I don’t think the relation goes in one direction. I mean more that democracy cannot exist without fashion and fashion doesn’t exist outside democracies. You cannot have a real democracy when everyone is dressed the same way. That’s not a democracy, that’s a dictatorship. Democracy is about liberating the multiplicity of identities, wills, and desires, and fashion is an expression of this intimate form of democracy.

SA: Is this the line of reasoning that you and Alessandro Michele developed in your book together? I have to admit that I haven’t read it. The English hasn’t been published yet and the German just came out very recently.

EC: This book came out of conversations that we had—

SA: Does it take the form of a dialogue?

EC: No. We didn’t want to make a boring dialogue book. The book’s form is like that of ancient manuscripts of the Talmud or the Bible, where there are different voices speaking at the same time on the same page, commenting on one another. There are seven chapters where we try to state something new about fashion, beginning with the idea that philosophy is the best language to describe and think about fashion, and that fashion has a special relationship with philosophy. We claim that fashion is not simply a specific artistic discipline. It’s bigger than that. It’s no coincidence that when the early twentieth century avantgardes suggested that art and life should coincide, suddenly this practice of making garments became strategically important and the industry of fashion emerged. Garments are the most universal and mass social artefacts in our lives. Everyone has to wear clothes. That’s why dressing in certain ways became a Trojan horse that allowed art to enter the lives of every single human being. And, it allowed people to have a relationship to themselves that is mediated by art. This is why fashion is so powerful and radical from a political point of view.

Emanuele Coccia & Alessandro Michele

Another chapter suggests that the real capital of fashion is not Paris, it’s Hollywood. Whenever you think about Paris as the capital of fashion that’s because we are still obsessed with this idea that fashion allows you to distinguish yourself from other people. That it allows you to give yourself a higher status. But this logic of distinction is a remnant of the logic of the royal courts where appearance was devised to allow people to reproduce social hierarchies that defined society in a sensitive manner. But that’s not what fashion is actually for. Fashion is what allows you to give reality to an alternative destiny. That’s why it’s closer to cinema than we think. A garment is a part of a script or a scenario that you are writing or someone wrote for you that allows you to, for some hours of our day or for the season, to embody another destiny, another life. To be something totally different. That’s why, through fashion, contemporary cities are transforming into open air cinemas where everybody is impersonating characters and plots that are merging with one another.

SA: This feels related to the exhibition you curated at the ITS in Trieste. On the one hand, you presented these very far-out experimental designs that are like science fiction creations and on the other you deconstructed the dailiness of fashion.

EC: The exhibition was a reflection on how fashion is able to pass through borders, and how it can redefine our experience of geography, cultural geography. The contemporary system of fashion has been able to do that because of its specific history. Fashion may have been born in Europe but it soon became something that was not limited to it. And it cannot be limited to a specific geographic region, otherwise it would be folklore and not fashion. Historically, it should be remembered that European fashion was transformed by Japanese designers and then became a global language. So, fashion expresses something that goes way beyond the place where you were born and live and it’s a language that is understood by everyone on the planet. This ability to produce a planetary language is extremely important today because we need forms of culture that can address all cultural identities.

And then, another question was: how is it possible for certain forms—trench coats, shoes, t-shirts, jeans—to be meaningful in themselves but also open to transformations that add meaning to these basic meanings? We try to enumerate these basic forms to understand the basic language of fashion today. They are in a sense the freest forms since everybody is allowed to use them and change them in their own practice. Everyone can speak through them, no matter where you’re from.

SA: And this is then contrasted with the experimental designs from past ITS competitions?

Installation view “Fashionlands: Clothes Beyond Borders” at the ITS Arcademy Museum of Art in Fashion in Trieste

EC: It wasn’t a contrast. We were more interested in activating the archive of this institution filled with the final works of students from all over the world. What’s amazing about them is that they are not projects of people working in the fashion system—

SA: And yet, if you look at past winners, basically everyone ended up going to major luxury brands—

EC: Yes, that’s true. It’s really impressive to witness what has happened at the ITS in the first 20 years of its existence. It’s such an important institution because it’s important to remember that fashion is mainly about dreams and not sales. And so, what’s amazing about the pieces in their archive is that they’re projections of people who just finished their studies and embody a form of a dream of what fashion should be. Or what it could have been or, in some cases, did in fact become.

SA: Is curation another passion of yours?

EC: The story goes like this. I wrote books that were mainly read by artists. So, I started having deep conversations with artists over a long period of time and then at some point the Fondation Cartier asked me to help with curation in Paris. It was not something I studied or thought I would ever do but then I discovered that exhibitions are perhaps the most contemporary form of knowledge production. You’re not using the words of a writer’s language, you’re using smells, colors, performances, and sounds to trigger the emergence of an idea that is extremely concrete. When you put four of five objects together in a room, suddenly they’re speaking about something else. What’s also interesting is that you’re not speaking when you make an exhibition. You let the work speak in your place. It’s a very strange exercise in ventriloquism or animism and totally different from the fetishistic relationship to written language dominant in academia.

Credits

- Text: SHANE ANDERSON

Related Content

Transcending Traditional Fashion Discourse with Massimiliano Giornetti

The Book of Gucci According to Alessandro Michele

Officecore with Gucci

Transmissions – Post Script: Couture Coda from Valentino in Venice

The Body as Sculpture: Viviane Sassen

“Seduction is a philosophy, and the fashion world is nothing less than a world of temptations.” In the Garden With LAETITIA CASTA

AZZEDINE ALAÏA Loves Animals & Women