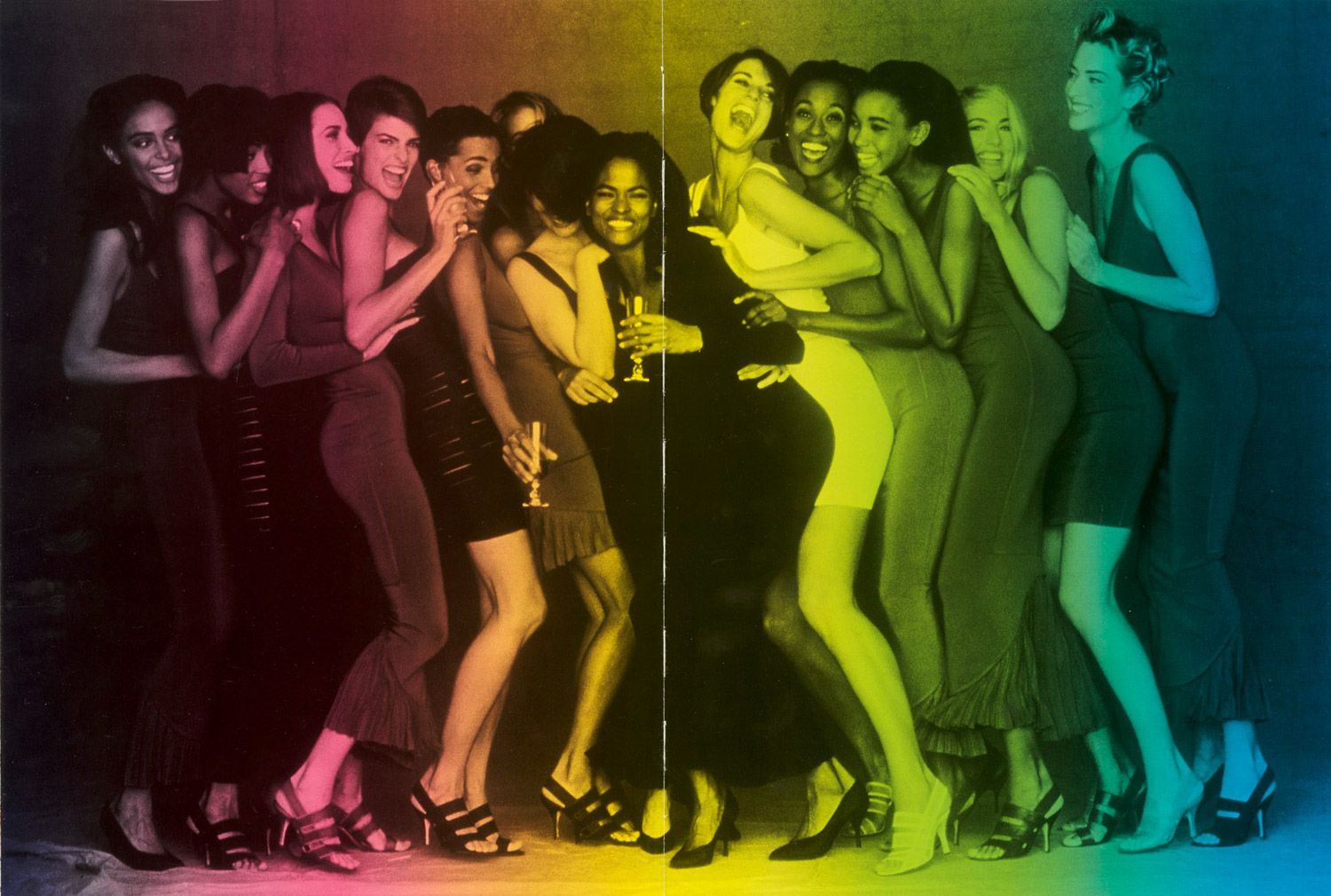

AZZEDINE ALAÏA Loves Animals & Women

How the son of Tunisian farmers made the sexiest clothes for the most beautiful women on the planet, rejected corporate fashion and became revered among critics, designers – even first ladies.

When asked about his inspiration for Louis Vuitton’s Spring 2011 collection, Creative Director Marc Jacobs simply answered, “fetish.” He cited a conversation about women he had with LVMH founder and CEO Bernard Arnault – the executive summary of which is simply that women are “inexplicable” – as the primary source for the idea. The result was a bondage-oriented Louis Vuitton défilé featuring a surprise appearance from a hot pants-clad Kate Moss smoking a cigarette as she strutted down the runway.

The event might be seen as a diversion from another, far more awkward fashion moment that occurred in Paris shortly before Fashion Week: John Galliano, intoxicated in a bar, declares his love for Hitler. Thanks to viral video, the whole world becomes aware of the fact within minutes. Whether truly anti-semitic or simply disgruntled, Galliano is promptly fired from Dior – another company in which Arnault is the majority shareholder. The label goes on with the show, minus one head designer.

The house of Dior was not alone in that predicament, however: Balmain also had to proceed without Creative Director Christophe Decarnin, this time due to a nervous breakdown that caused the designer to vanish from his post in January, and be terminated, in absentia, in April.

The pressure in the fashion industry is notoriously high. A tense mixing, perhaps, of the creative and the corporate, fashion makes for a bipolar environment, changing its mood with every turn of the season. In recent years this has escalated into the retirement, the downfall, and even the death of some of the industry’s greatest luminaries – but is anyone asking questions that might lead to change?

It’s a sunny spring day in Paris. The shows are over. Not much remains, except ever more open, inevitable questions.

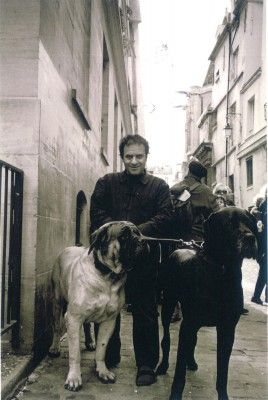

Rue du Moussy is the only place you can seriously look to for answers these days. It’s the home and workplace of the great couturier, Azzedine Alaïa, and it’s quietly outside of the usual spotlight. The boutique, the atelier, the showroom, the studio for private clients, the designer’s residence – it’s all here, under one roof. Artist Julian Schnabel created some furniture for the space, including a massive cashiers’ desk, emblazoned with the initials, “A.A.” Industrial designer Marc Newson – another friend – also contributed to the interior with a circular shoe salon. Alaïa is always present there. If he is not working in his atelier upstairs, he is wandering through the boutique or entertaining in his kitchen. That room is something like the heart of this place, where every day a chef cooks lunch and dinner – not only for him, but for his entire staff of roughly eighty people, and his frequent guests, who are always welcome – even when uninvited.

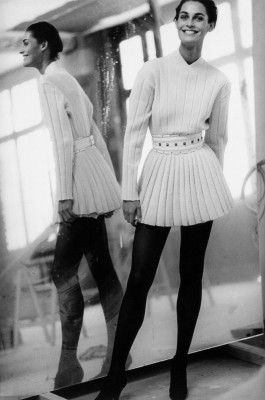

It’s also under this roof that Alaïa shows his work – that is, if he feels it’s time to show his work. For more than a decade, Alaïa has premiered his collections at his own rhythm, in discrete, private défilés. He creates one collection per season. He doesn’t advertise; very few magazines are sent clothes to feature. He rarely gives interviews, and makes no public appearances. This past March, his show seemed more exclusive than ever: a group of around thirty people, consisting of private clients, buyers, journalists, and friends, convened for a very low-profile event. No supermodels, no superstars. It was 2:30pm; there was coffee, tea, and petits fours. The stereo played Gloria Gaynor’s “I am what I am” as the models walked – wearing knitwear only, in that striking Alaïa shape. No leather, nothing luxurious, and twenty minutes later the show ended to “I will survive.”

Azzedine Alaïa is the inventor of “wearable sexy.” He brought leather and Lycra into high fashion, and still experiments with underused materials today. A sculptor of fabrics, Alaïa has profoundly impacted the silhouette of the modern woman. He oversees every stage of garment construction; he dictates the way in which a garment should be worn. It would be near impossible to find a voice in fashion that would not speak of Alaïa with admiration.

AZZEDINE ALAÏA: I can only speak for myself, but for a long time now the system of fashion has had nothing to do with our time – it doesn’t suit our time at all. The world is changing rapidly. We see the proof of change every day in the news. Young people want change in this industry, too, yet we continue, just like in the 19th century, to do défilés. There is no need – no interest, really. We could do fewer collections and obtain the same results. We don’t lose any money if we do less.

Is money really the only concern?

Creativity should be the only concern. But today there is no time for creativity; nobody has time to develop a special silhouette or a special fabric. Of course there are a few exceptions, like what Nicolas Ghesquière does at Balenciaga, or Alber Elbaz at Lanvin. But designers working for big houses like Dior or Vuitton have no time to reflect. We can’t just squeeze the young talents out like lemons and then throw them away. Four collections for women, four collections for men, another four collections to sell, and everything has to be done within four-five months – it’s a one-way course towards emptiness. It’s inhuman.

You’ve been showing clothes at your own pace and in your own house for a while now, but this season it seemed especially exclusive, focusing solely on knitwear.

Maybe in July I will show other clothes, if I have the time to develop them. I refuse to work in a static rhythm. Why should I sacrifice my own creativity to that? That’s not fashion, that’s industrial work. We can hire people to design all day long and then fabricate what they design and sell and sell and sell – but that has nothing to do with fashion, with la mode. And it’s a shame talents are being abused for this. I really don’t understand that. I have to live as well. That’s what life is about: living. Tell me how these designers who work for the major houses can have lives? How can they raise children if they are never home? They are gone for one, sometimes two months, while their children have to go to school. They have husbands, wives, but they can’t live their lives. People need time for that, and talents need time to create something. It’s stupid to ask someone to create eight collections per season. Look what has happened to John Galliano or this poor young guy from Balmain, who is now in a psychiatric hospital. After five or six seasons, he was already broken. OR last year, McQueen – dead. And there are many more that are just so tired. There is a pressure that is mad.

I first need to work on the fabric: I need to cut it, think about the shape, drape it on the bust – reflect on it. I make every piece with my own hands. And this season, where I decided to show only knitwear, I sold two times as much as I did last season. You know that at Barneys in New York I got a 140m2 space just for me, for my clothes? If you do one beautiful skirt per season, that already is a miracle. If you do one manteau that women desire, you have won. You don’t need to do long coats, short coats, one with a zipper this way and another one with buttons that way.

Also, people travel a lot today. Seasons are not what they used to be – we go skiing in the summer, swimming in winter. We don’t need to think in seasons anymore; we need to think about beautiful clothes. We really have to do something about this situation in fashion.

What do you do to deal with that?

I remote. I don’t do fashion just for the show. I have done it in the past, but I stopped. There are other problems to solve, so I moved away from such frivolous things. I give myself time, as much as I need. I am not afraid to lose. As I say, you need one miracle piece – nobody can do a ton of great clothes. And Alaïa is expensive, like couture – it’s luxurious, like all high fashion brands. I don’t know why people in fashion don’t treat it as luxury anymore.

You have said before that we are missing philanthropy in fashion.

New talents, like Haider Ackermann, really have to watch out for themselves. The decision for someone like him is hard – to be approached by a big maison and then say no. But signing a big contract is like signing a contract with the devil today. He can’t do his collection and do, for example, collections for Dior. Of course there are exceptions, like Karl Lagerfeld – he can do Fendi, he can do Chanel he can do photos, film, Diet Coke – but that’s something very different. There is just one Karl Lagerfeld – it’s a whole other system.

What about your system?

I just concentrate on the clothes I make. I think, “Why do I make clothes? What should the clothes I make be about?” There is just one good reason to do fashion: to make the woman look more beautiful. If that is not the case, it has no meaning for me to create. And it has no meaning for her to buy something that massacres her style. I truly never calculate – I only think about women when I create. And I owe it all to the women, all my success.

Monsieur Azzedine Alaïa is the Last Couturier. Everything he creates, he creates with his hands on a bust – to feel the movement of his creations he even maintains a fitting model in residence. Every piece is hand-made. The clothes, as he says, are there to make women even more beautiful. That is his goal. Because fashion used to be about spirit, a reflection of a certain time. Designers used to create silhouettes that fit that attitude towards life. Today, fashion is an industry; money keeps it going. Advertisers have the power. We have more choices than ever before, more topics to reflect on – and less and less content.

Are you interested in money?

Only to spend. And of course I had to learn, and I have learned, it’s good to have it to be able to do things.

Are you interested in success?

Everyone is! Even a sweeper is interested if you say he sweeps well. It shouldn’t go to your head though, because it’s not for ever. I am not pretentious in such things. You know, from the beginning I could have been the best paid stylist. I have been offered the highest paid contracts in the world. I refused them all. It’s not my thing. I don’t want to cheat people. And there are certain people I am allergic to. I even intervene when I don’t like a customer; I rush in and check all the names. If I don’t like them, I don’t take them.

What keeps you going?

I don’t let things get to me.

How many hours a day do you work?

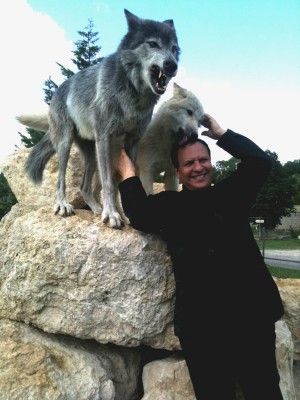

I begin at 9 am and I go to bed around 2 am, sometimes around 3 am. I sleep little. If I’m not working or entertaining, I love to watch the National Geographic channel. It takes my mind off business. I don’t take things too seriously, though – in this system, you are closed in. You will wake up one day and you will think, “Shit, what have I done?” You have to take things with a lot of laughter. I laugh with everyone, this way I will be able to die happy. And I put myself on the same level as everyone else around me – from the directrice to the workman, everyone. Except my pets – they are the Kings; you must treat them like royalty.

Four or five hours of sleep – is that enough time to develop a dream?

I don’t waste time when I sleep.

You are a Pisces – do you believe in astrology?

I believe in nothing – not in religion, not in astrology, not in superstitions. Honestly, how can I believe in one religion when I live in a house with so many different people? How can I say my religion is better than his? What about all those cemeteries? Is one going to lead to paradise and the other to hell? But I do sometimes say, “Oh, god,” and when I go to church, I light candles; in a mosque, I’ll try to mutter a few prayers, which I don’t know well. I always think it might be worth trying. You must be good, I understand that, but when I have a problem I call on all gods – that way maybe one of them will be able to answer me.

Those who do believe in astrology say Pisces are sensitive and vulnerable – do you identify with that description?

Sensitive, yes; vulnerable, no.

How would you describe the man I am facing right now?

I don’t try to understand myself. I live more like this: every morning when I wake up, I ask myself, “What will I learn today?” Really, it’s true. When I wake up I am happy to open my eyes, happy to be alive, to feel good, to have no diseases. And then I ask myself, what will I learn today? Who will I get to know today? I am a very curious person. The beauty of working in fashion is it gives you the possibility to meet a lot of people – interesting, amazing people. I think I’ve met the most interesting people of my time, from all fields, and I am very grateful for that.

What have you learned today?

The day is not over yet. But I promise you I learn something new every day. And I want to try to keep it that way, until the day I die. Even in designing, there are so many things I still have to learn. I’ve been trying to manipulate clothes for thirty years, but I know I can still get better. Sometimes I redo one thing five, six times. I am always in doubt; I am never sure of myself. Even when you tell me I’m an influential designer – I don’t see myself like that. So I don’t like decorations. You know Sarkozy offered me the Légion d’honneur medal? I refused. People said I refused because I don’t like Sarkozy, but that’s ridiculous. I refused because I don’t like decorations – except on women. My dress on a woman – that’s a beautiful decoration.

ABOUT AZZEDINE ALAÏA

Alaïa was born in 1940 in Tunisia where his parents were wheat farmers. His twin sister, who loved fashion, taught young Azzedine about sewing and style. At seventeen, he got himself into the École des Beaux Arts to study sculpture. After graduating he started working as a dressmaker’s assistant, and soon after, in Paris, as a housekeeper and dressmaker for the Comtesse de Blégiers, who introduced Alaïa to Parisian high society. The rich, the famous, and the glamorous – such as Greta Garbo, Marlene Dietrich, and the ladies Rothschild – became his first private clients. Alaïa eventually began working for Christian Dior, later for Guy Laroche, and later still for Thierry Mugler, before opening his own atelier, in his apartment, in 1980, on the infamous Rue de Bellechasse. He achieved immediate fame for the clarity of his designs: princess-line coats, ice-skating dresses, shapely knits. He gave new life to leather at a time when it was reserved for sex-workers. His dramatic, skin-tight garments began to sculpt the feminine form as it had never been sculpted before. He defined “body-conscious,” and became the designer of the eighties. He not only launched the careers of models like Naomi Campbell and Stephanie Seymour – perfectly suited to his silhouette – but he brought them into his home. He has been friendly with the most influential and creative minds of his time, from Andy Warhol to Madonna. His creations have been photographed by the likes of Arthur Elgort, Peter Lindbergh, Helmut Newton and Jean-Paul Goude, to shape some of the strongest images of the eighties. During the mid-90s, following the death of his twin sister, Hafida, Alaïa retreated from the “fashion scene.” He began to present in his own space in Paris’ Marais, to a more or less private clientele. In 2000, he signed onto a partnership with the Prada Group, and in 2007 was going strong enough to buy back his name. Today, Swiss luxury good holding company Richemont is the discrete supporter of the Maison Azzedine Alaïa.

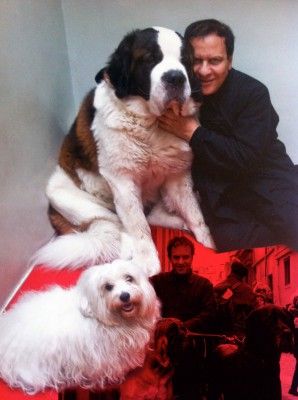

Alaïa’s remain the ultimate modern silhouette, timeless and desirable across generations of women. Despite an eighty-strong staff, he does not consider himself to be the true head of the household: “My animals, they are the patrons of the house.” Alaïa has two Norwegian Forest Cats, two Bengals, and one Persian, called Oum: “She is the most capricious one. She sleeps with me,” he says. He had only two dogs until recently, when Shakira offered him a third – a Saint Bernard. “And I just got a magnifique owl,” he says, which was to arrive shortly after we spoke. A massive cage was all ready and waiting in the courtyard behind the kitchen.

By JINA KHAYYER