The Body as Sculpture: Viviane Sassen

|MAX ROSSI

Fashion photographer and artist Viviane Sassen has spent decades studying the body, but not anatomically. By focusing on its relationship to space, texture, and subconscious undercurrents, she transforms her subjects into living sculptures, pushing beyond the human form.

Viviane Sassen, Self-portrait, from the series “Self-Portraits” (1989–1999). Courtesy the artist

Sassen’s practice, mostly focused on photography, puts art and exhibitions in dialogue with editorials for the likes of Miu Miu, Stella McCartney, Armani, and Louis Vuitton, as well as iconic covers for Dazed, AnOther, Purple Magazine, and Frieze. Surrealist themes and archetypal narratives run through her work, yet her most enduring influence is personal: childhood memories of Kenya, growing up beside a polio clinic where her father worked, witnessing bodies altered by disease.

Viviane Sassen for Another Man

Her latest exhibition, “Body as Sculpture” at Fotografiska Berlin, traces her journey through one of her foundational themes—the ever-transforming body. Unfolding chronologically, the show features key works from 1989 to 2024, spanning photography and video installation: from her early experiments in Self-Portraits (1989–1999) and Folio (1996–1997), to explorations of fecundity and femininity in Of Mud and Lotus (2017), Versailles’ hidden history in Venus & Mercury (2020), surrealist grotesque collages in Consequences / Cadavre Exquis (2020–2024), and a tribute to her fashion practice in Mode (1994–2024).

A few days after the opening of “Body as Sculpture,” Max Rossi sat down with Sassen to discuss the connection between the physical and subconscious, balancing a personal practice with commercial work, and the limits of traditional photography.

MAX ROSSI: I read in your exhibition biography that your artistic journey began with a shift—from fashion design to photography. What led to this transition?

VIVIANE SASSEN: Pretty quickly, I realized I wasn’t meant to be a fashion designer. It turned out I wasn’t all that interested in clothes or how they were made—what really drew me to fashion was the imagery, the photography in magazines. In my second year of fashion studies, we had workshops on technical drawing, pattern-making, and sewing, and I thought, “Oh no, this really isn’t for me.” Around the same time, I started modeling, which put me in touch with a lot of photographers. That’s when it clicked—I wanted to do what they were doing, to be behind the camera, shaping the image. As a model, I kept trying to influence the shoots, throwing out ideas, but most of the time, the photographer was male. And that’s when I realized I didn’t just want to contribute to the pictures, I wanted to create my own.

MR: Did you want to photograph only fashion or also adjacent fields?

VS: I wanted to explore the medium as a whole. I’ve always had a love-hate relationship with fashion, but ultimately, it became a powerful tool for getting my work out into the world. As a young photographer in the mid-90s, what else could you do? We organized our own exhibitions with other young photographers, but that remained very local, here in Amsterdam. I quickly realized that if I wanted my work to reach an international audience, fashion photography was the perfect vehicle.

Viviane Sassen for U la Repubblica

MR: In your photography, you reshape the body to reclaim it from the rigid male gaze—yet your subjects remain undeniably sensual. How do you navigate this tension without falling into another gaze-centric narrative?

VS: What about the female gaze? I think many women can appreciate the female body without any ulterior motives—there’s a lot of beauty in the female body, but also in the male body. I don’t really make a distinction. There must be some overlap in what men and women find attractive or arousing. I’m not concerned about stepping into a different kind of male gaze. In fact, many of the images I’ve created of women, especially the more erotic ones, were made with an entirely female team, with no men involved.

I’ve never really explored to what extent my own gaze is influenced by the male gaze we’re all raised with, but it would be interesting to investigate. Generally, I try to avoid making work that’s too political, though of course, any work can be viewed through a political lens. But I try to stay away from it, even though it’s hard these days because everything seems to have become political.

MR: Do you think erotic photography is still often seen as primarily for the enjoyment of men?

VS: It’s not. Take a dancer or a pole dancer, for example—if she’s really good, you’re in awe. It might not arouse me in the same way it might a man, but there’s still something captivating about it. I remember when I was in art school, we would draw nude models every week, and I always found the male bodies more interesting to draw. Their musculature and the sharper lines that run over their surface made them more intriguing to me.

MR: Your work fragments, distorts, and abstracts the body. Do you see this as a form of resistance, or is it just an aesthetic preference?

VS: I don’t think it’s about resistance, no. Maybe it has to do with the fact that I was trained in fashion for a few years, which influenced me in a certain way. When you’re in school learning to design, everything starts with the body. You create shapes and forms, transforming the body into something else. I was fascinated by that from the very start. Ultimately, I think of my work as creating these extended shapes of the body. They belong to you, but also don’t—it’s about transformation. What interests me in photography is that when you show people and bodies, you can tell a story, but not necessarily a narrative. With fashion, it’s always about transformation in some way, and you can see that inner process reflected on the outside. It’s a translation of inner thoughts and ideas into the tangible world, something with form, shape, and structure.

MR: Your compositions remind me of Mikhail Bakhtin’s concept of the “grotesque body”—one that is formless, constantly becoming. Do you think fashion embraces this fluidity, or is it still shackled by rigid aesthetic ideals?

VS: I think it’s both. They can coexist. Most of us still have two legs, arms, a waist, a belly, a head, and so on, so it makes sense to design clothes that fit those basic shapes. But when you look at today’s fashion and see the work of designers like Duran Lantink, Jonathan Anderson, or Rick Owens, you can see how they use bodies and fashion as sculptural tools, extending and transforming conventional shapes.

MR: Many of your images obscure faces, distort limbs, or use shadows and objects to erase identity. Is anonymity a tool of liberation? What role does it play?

VS: Most of all, I’m interested in the abstract and the universal idea of what it means to be human, rather than focusing on a specific individual. When we see a face, we’re instinctively programmed to decode something from any expression and form an image. I tend to gravitate towards the anonymous because it reveals less. In this way, the subject becomes more universal.

MR: Almost like archetypes.

VS: Yes, exactly. Archetypes and mythological symbols—I'm more interested in exploring that.

Installation view of Vivian Sassen, Mode, part of “Body as Sculpture” Fotografiska, Berlin, 2025. Courtesy Fotografiska, Berlin. Photo: the author

MR: How does your approach differ when working within the commercial framework of fashion versus your personal work?

VS: It’s a huge difference. I see it as a spectrum with two poles—on one side, there’s very commercial work, and on the other, there’s artistic or personal work. In between, there’s a whole space to explore. For example, fashion editorials tend to lean more toward art, offering a lot of creative freedom to experiment. So it’s not necessarily a completely different world.

When I work on commercial projects, I see it as solving a puzzle—it has to fit their needs. If it’s a big name, I hope I can contribute something to the process, but I’m not seeking more creative freedom. Sometimes, less is actually more interesting to me. I have my own art practice where I can express myself without any rules. A commercial job needs to check off many boxes; and while it can be challenging, it’s also deeply satisfying once it’s done.

Frank Ocean by Viviane Sassen, shot in Japan, 2015

MR: Do you ever feel restricted when clients typecast your aesthetic direction, making it harder to evolve?

VS: That happens, yeah. Clients sometimes come to me asking for a “real Sassen,” and I think, “Oh god, here we go again.” I don’t want to repeat myself—I like to explore. I create large collages, but lately, I’ve also been working on very different projects that lean toward minimalism, focusing on nature, patterns, and structures. The balance between familiar and new work gives me space and creative freedom. It’s reassuring to know I’m not reliant on just fashion or just art.

MR: Can you talk about the inspiration behind “Body as Sculpture?”

VS: It was quite pragmatic: they wanted me to present my retrospective, which I had already shown at La MEP (Maison Européenne de la Photographie), but it simply didn’t fit into the space here in Berlin. We had to make some choices. I tried to edit it down, but I quickly realized that wasn’t going to work—there was no way to narrow it further. My extensive work in Africa needed to be included, as well as Umbra (2014), a defining moment in my practice.

So instead, Marina Paulenka, the curator of “Body as Sculpture,” and I decided to shape the exhibition around the idea of the body—a recurring theme in my work that has evolved over time. I think you can really see how my early work connects to what I create now, bridging both sides of my practice—fashion and fine art. That became the foundation, and from there, we structured the show chronologically to highlight how these works have informed each other over time.

MR: How did Umbra affect your artistic choices?

VS: It was about the shadow—both in my work and in the psyche, much like Jung described it as something we all carry within ourselves. I created this project years ago while revisiting the loss of my father, using my art as a way to process grief. It’s deeply tied to death and the existential fear of it, something that has stayed with me for a long time.

My father was a doctor, and his practice was at home, so sickness and death were ever-present in our daily lives. He passed away when I was 22. He ended his own life. That loss has profoundly shaped both my life and my work. Umbra was, in many ways, an attempt to come to terms with that chapter of my life.

Viviane Sassen for Louis Vuitton, 2022

MR: In your installation Venus & Mercury, which is included in “Body as Sculpture,” you combine your photos with Marie Antoinette’s private correspondence and close-ups of classic statues, and texts by the Dutch poet Marjolijn van Heemstra to hint at the untold stories of Versailles. What does a place like Versailles symbolize to you?

VS: I was invited to Versailles to participate in a group show of five photographers, including Nan Goldin, Martin Parr, Dove Allouche, and Eric Poitevent. The only condition was that the work had to be connected to Versailles in some way—but the interpretation was completely open, allowing us to make it as abstract or conceptual as we liked.

I photographed certain sculptures, including some in the restoration atelier across from the palace, where many had missing or damaged body parts. I also delved into the history of Versailles and uncovered stories that revolved around power dynamics between men and women, as well as shifting moral standards—particularly in relation to sexuality.

It all ties back to the body. Walking through the vast gardens, surrounded by grandeur and beauty, it’s easy to forget that Versailles was shaped by flesh-and-blood people who built it and lived there. It’s them who made it interesting–there were lots of sexual scandals, and the title Venus and Mercury references syphilis, which they used to treat with mercury.

MR: Your early work was strictly photography, but you later expanded into collage, video, and installation. What pushed you beyond the still image?

VS: What I find interesting about collages is that they allow me to break free from the frame’s limits. I can create compositions that exist beyond those boundaries, almost floating on the wall or suspended in space.

MR: Is it also a way to artificially influence the composition? You can only do so much with photography and posing…

VS: Yes, exactly. There’s only so much you can do. For quite a while now, I’ve been using ink and paint to alter my pictures, along with collage techniques, and have expanded into larger objects, almost in three dimensions, as well as video installations like you can see here in Fotografiska. Surrealism has always been a major influence on me. As a child, and even more so now, I’ve felt drawn to the dream world and my life at night when I’m dreaming. The subconscious is deeply connected to oneiric worlds and Surrealism, and given the current state of the world, with all its absurdity, Surrealism feels even more real than reality to me.

It’s also interesting to note that Surrealism in the 1920s was also a political statement. While I tend to steer away from those, there is still an undercurrent in my work that subtly mocks the status quo. It makes sense to me, because Carnival itself is a reflection of the world turned upside down. In today’s world, people need an alternative reality to cope with what’s happening out there.

Credits

- Text: MAX ROSSI

Related Content

The Politics of Beauty: Tyler Mitchell

How to Start a Fashion Magazine?

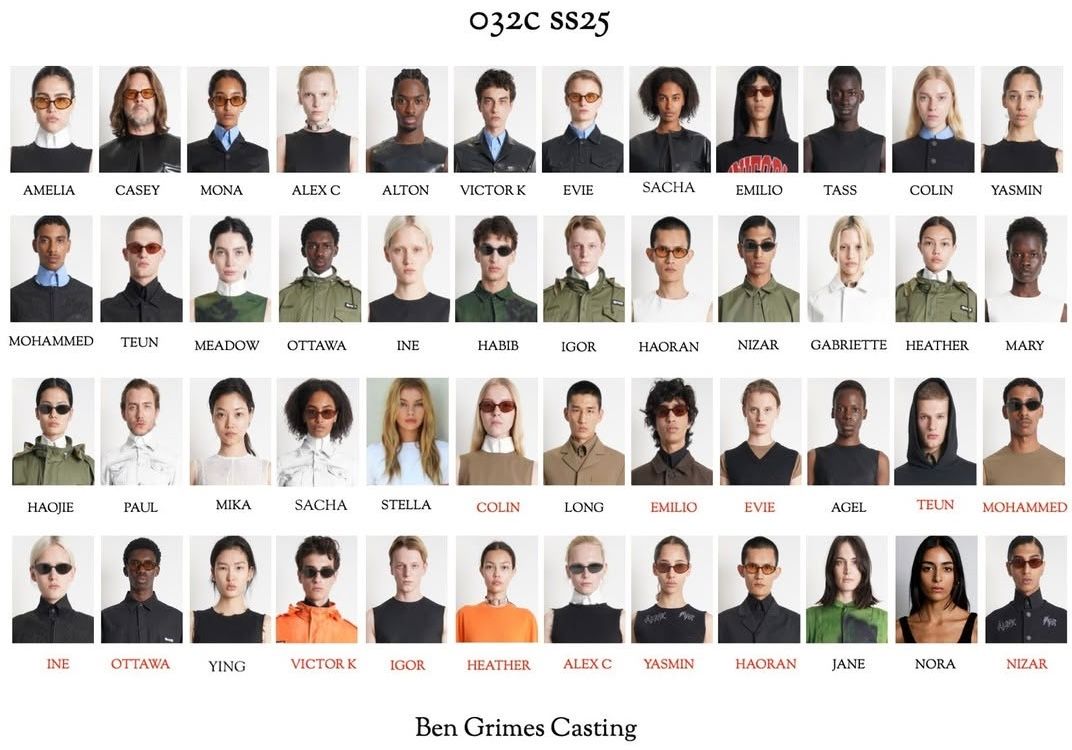

How to Cast for a Runway Show with Ben Grimes

Women Who Run With the Wolves

Mire Lee’s Fountain of Filth

The Denatured Machine

Officecore with Gucci

HR GIGER & MIRE LEE: Horror, Slime, and Satanic Eroticism

Marc Kalman’s Definition of Boyish

What’s Your Religion? Dior Tears

The Erotics of the Nerd

Ways of Smelling with MATIERE PREMIERE