The Human Stain: Helmut Lang at the MAK Center at the Schindler House

Helmut Lang, fist I and fist IV, 2015–17. © Courtesy of the artist.

Tucked away on a quiet residential street, far from the commercial buzz of West Hollywood, stands the vestige of a radical mid-century social experiment. In 1921, architect Rudolph Schindler built a home that was designed to be a communal live-work space for two families. Making novel use of industrial materials, the minimalist, earth-toned house features sliding panel doors, exposed concrete walls, and a striking absence of a living room, dining area, or bedrooms. Schindler and his wife lived there with architect Richard Neutra and his family for five years. Later inhabitants included photographer Edward Weston and composer John Cage.

Today, the Schindler House serves as the headquarters of the MAK Center for Art and Architecture. This spring, it is home to a series of artworks created by Austrian artist HELMUT LANG. Displayed across five different rooms, “Helmut Lang: What remains behind” presents a series of sculptural works made of mattress foam, wax, resin, shellac, and latex. The light-catching structures are only faintly figurative, yet overtly corporeal in their allusions. With titles like Fist I and Prolapse II placed in relation to one another, the exhibition highlights the erotic subtext of both the artwork and the architecture. The ghosts of past relationships loom in the exhibition’s atmosphere.

Installation view of Helmut Lang: What remains behind at the MAK Center for Art and Architecture, Schindler House, Los Angeles, 2025. Photography by Joshua Schaedel.

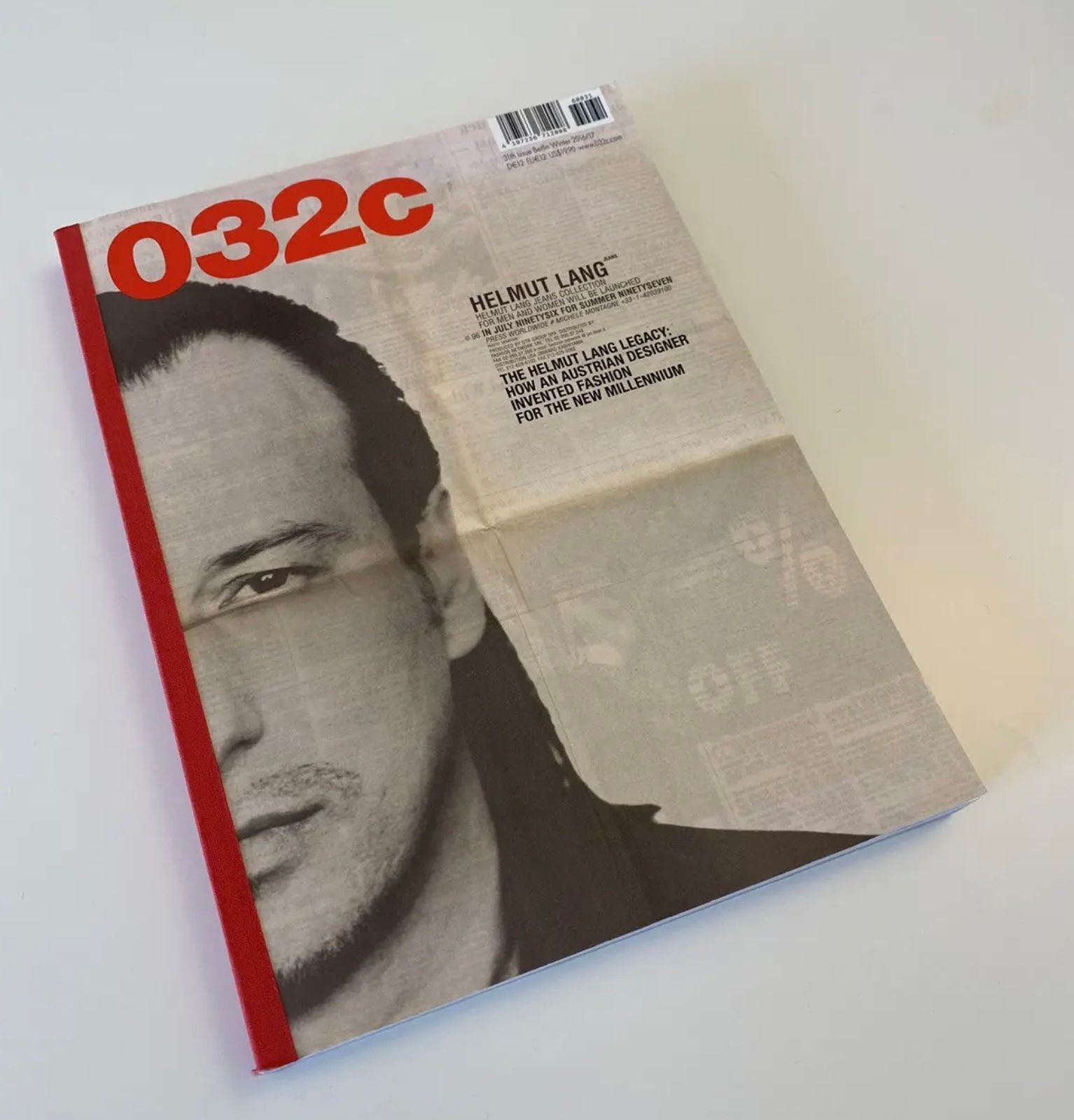

Helmut Lang rose to prominence in the fashion world in the 1990s, before stepping away from his eponymous label in 2005. In Issue #31, 032c explored Lang's legacy and why his abrupt exit "has been felt like a phantom limb in the world of fashion." The deconstructed aesthetic and commitment to unconventional materials that shaped his explosive design career live on in his artistic practice, which explores themes such as identity, memory, and the body through the manipulation of tactile media.

Curated by writer and curator NEVILLE WAKEFIELD, “What remains behind” is part of his broader exploration into how art functions outside traditional institutional frameworks. On March 31, Wakefield discussed the exhibition in a public conversation with writer, curator, and professor HILTON ALS at the MAK Center at the Schindler House. The following is a condensed and edited excerpt thereof.

Neville Wakefield (left) and Hilton Als' (right) public discussion at MAK.

Hilton Als: I am ashamed to say that I didn’t know anything about this house and had not seen any of Helmut’s art before. The house feels like a vessel to me—like something that is going to sail away. Simultaneously, Helmut’s imagination sails in many different directions at once. How did this cohabitation happen?

Neville Wakefield: Helmut had been invited by the MAK. This house, which for me is one of the hidden gems of Los Angeles architecture, is obviously not a white cube, it is a vessel replete with human history, experimentation, and dialogue. So, the idea of combining Helmut’s work with the work of R.M. Schindler, two Austrians, framed a dialogue, in a way only a place like this can. None of these sculptures were made with the intention to be presented in this space, yet there still is an incredible dialogue.

HA: What was so astonishing to me when I came by yesterday, is that I couldn’t leave. I think it is because of the illumination that comes from the work, which is what is so extraordinary about it. This illumination from the sculpture in the rooms, which are fairly dark, felt captivating. I didn’t know—and I didn’t want to know until I spoke to you—about the materials that Helmut used to make these particular works because there was a certain thrill in not knowing. But perhaps you can now share what materials he was using?

NW: The internal luminosity came from the wax pieces that are made of foam. All the materials that Helmut used had a life before. The foam, in particular, physically has human interaction impressed upon it, “the human stain.” They bear the scars of their making.

In a similar way, you can see the imprint of the building’ making; the imperfection of the slabs and the presence of the human. This building, as well as being a formal experiment, is a social experiment, an experiment in new ways of living—new promiscuity and destroying conventions. It’s the idea that things spill out of their containers no matter how much you try to contain them. They’re sort of hemorrhaging outwards and we’re always negotiating a threshold of interior and exterior space. Which is obviously particularly relevant here.

HA: When I was walking through the rooms, I started to feel like I was living in a science fiction story. I felt like my body was a new shape because of the accommodation of the sculptures and the ceilings. If you're a tall person, you have to bend down. You then have a different relationship to the space.

So, one of the things that fascinates me is the juxtaposition of these sculptures with the material of the walls. In fact, as the audience, you are interacting with something that is solid and temporary at the same time, because even though Helmut’s work is not time based, I feel like he is interested in the illusion of time. Do you have that feeling as well?

NW: Definitely. For some of his sculptures, he’ll leave them outside. He is quite happy to accelerate or even embrace the entropy as part of the process. There are also different registers of time: the historical architecture, the architectural time, and the sculptural time—they’re all in dialogue with one another. And then, like you mentioned, the science fiction time.

HA: In terms of the science fiction aspect, it felt like when you see a crying baby. In that moment, you feel deep sympathy for the baby but you also feel completely repelled at the same time. Helmut’s work seems to love inducing being seduced and repelled simultaneously. In my research, I found a conversation between you and Helmut where you talk about surfaces, and you compare them to relationships. Surfaces where something could be cast off or embraced also perhaps offer connection. Are the totems in this exhibition totems that protect us or are they taboos that have been manifested?

NW: I think they’re both. I think Helmut is completely open about how these pieces get interpreted and is very generous, letting the viewers create their own impression. The work was born from the challenge of turning inner experience into outward form. The floor pieces are titled Prolapse, so you already got the idea of the body’s container not being able to contain itself and spilling out which is both a repulsive and beautiful idea.

HA: I also felt energized by the sexual energy of the pieces. I know that creativity and sexuality go hand in hand but when I was in the space it felt like I was lost with the art and that I did not know where I was. He is pushing me against the wall to make a point. The work was not aggressive in a sexual way—it was more knowledgeable about the body. That might have to do with his past as a designer.

NW: It is very hard to pin down what the sexual energy of these pieces is but there is something innately sexual in the manipulation of the material. Maybe you could decipher it better than I can.

HA: Maybe because I am a homosexual, I feel that it speaks to me as if I’m being confronted by another gay man. One of the things you’re taught very early on is to be ashamed and to hide your sexuality on some level—to not let people know who you are completely because you might be attacked. So, while the earlier works in these rooms were more opaque, the atmosphere now is more out there. It’s not making an apology for that type of energy. I want to talk to you some more about this manipulation of materials and where Helmut got his inspiration from.

NW: I do not know if he was necessarily inspired by this, but when I think of Helmut’s work, I think of John Chamberlain, because of the plasticity and animation of the pieces. The first body of art Helmut produced was largely from his archive. He shredded these materials, perhaps as an act of rejection of the past or transformation of it. They were set in these epoxy resins that were both hard and opaque. It’s similar to these newer works which capture the light, and transform as you move around and engage with them.

HA: What initially drew you to his work many years ago? Because it was less dramatic and it was much more to me pulled back than the work he’s doing now. I’m interested in what you saw in the mystery of the early work.

NW: I think it was more about the process. I am speculating, but it is the processing of the [distant] past and the immediate past and his long and extraordinary career as a designer. For me, the Prolapse sculptures almost feel like sites of trauma.

HA: Or even the remains of trauma. Or something left behind at a crime scene. Speaking of trauma, I wanted to ask you about your family. Like all great curators, you’re interested in telling a story, and on some level this always relates to one’s own experiences. One of the things that came up in my research about you was that your dad was a potter and you basically grew up outside with your sisters.

NW: Yes, my father was an artisan, not an artist. I grew up in a quite feral environment with my three older sisters. It was on a very remote island where we didn’t have access to very much but was a place of great physical freedom. We explored and did things that I would never let my children do.

HA: What was that like when you then went out into the world? Was your interest in art fostered by that experience?

NW: I think art then became a language where I could somehow negotiate between physical expansiveness and freedom.

HA: Do you think the work you’re drawn to verges on sort of crossing out the definition of art, as “things on a wall?” Were the distinctions of art versus not art irritating to you as you began working as a curator?

NW: I do not know whether they irritate me. It’s more that I had to learn to work in a controlled environment, since the environment I grew up in was never controlled. There’s a kind of curating where you’re trying to eliminate every variable—climate control but also narrative control—where the portal to experience is monitored by a series of social, architectural, and even ontological barriers, as if, were you to go into this white space without a certain knowledge of art, it would not make sense. I was interested in what happens when you’re more transparent. In a funny way, I think that relates to this exhibition of Helmut’s sculptures as it, in the broadest sense, is a dialogue between interior and exterior space. Whether it is characterized architecturally or on a human psychological level, such a dialogue seems to be the primary purpose.

HA: I think I can speak for most viewers when I say that my first experience with art had a lot to do with not understanding what was happening. You walk into a museum and you do not really know what is going on. When I was young, I was once in MoMA alone but surrounded by a group of ladies. I went to see an exhibition that included a goat that was covered in paint and had a tie around it on this platform. I did not understand a thing but something told me to keep looking. I told one of the ladies that I did not understand and she told me to come back tomorrow and that she would walk me through it. She told me the next day that art can be whatever you decide. This dialogue always stuck with me as it gave me something to hold on to. I think that is what art is. The viewer has the desire to connect and the desire to expose themselves to something previously unknown.

As a curator, do you feel like a teacher guiding the viewer to something they perhaps might not have known?

NW: No, because I don’t think that it is that direct. I hope that invertedly the viewer arrives at some exposure to the subject. With a lot of public works, for instance, the audience is not art savvy and so approach it without preconception. That is one of the beauties of it. Also, seeing children understand the work in their own way is perhaps the most rewarding part of being a curator. That is not because they see my vision or that of the artist but because their mind is free to see whatever they like.

HA: How did you start doing curatorial work with Helmut?

NW: I was doing more site-specific work in Switzerland, for example with Maja Hoffmann, and what really interested me was how art behaves in uncontrolled environments; particularly, how the lack of control can be part of the product. How the work can collaborate with circumstances it doesn’t control—whether that’s nature, wind, or snow, etc. I was interested in the idea that the work then has a life of its own. Today at this house, in this context, all the stuff that you know about the museum or the etymology of the museum as mausoleum––things that were written in the 80s and 90s––does affect the work, but at the end of the day, the idea that art has a life of its own still remains true. An uncontrollable and unmanageable life.

HA: You are working with people that are changing the landscape in a lot of ways. Do you like that form of collaboration?

NW: I do. I think it tests me in the same way the result tests the audience. That is really important. We create narratives as curators and there is always a moment with the artist, who has their own concept behind the work, that has its own dynamic. I guess it depends on how you monopolize the situation.

HA: Yeah, the artist initiated the conversation and then it is our job to continue it. It is not just about expressing their goals but about being in conversation with them. It has been said that you do not rearrange the subject as a curator, you rearrange yourself. I do not think you could do a show of Helmut’s things without rearranging yourself. It was a very graceful exhibition because you let him have this new chapter of saying much more than just being in a space trying to find arrangements. You let him have this new chapter where he is much more out there.

NW: For sure. It was also such a joy and honor to spend nearly a week in the space with these objects, trying to find arrangements that made sense. I’m curious, what are the narratives that you drew from this exhibition?

HA: I think that it goes back to this feeling of drawing the viewer in and then pushing them out again. My personal feeling was that it was deeply sexual and emotional, and that Helmut was having his way with me. I even had to lie down after coming to the show because suddenly I was not myself. It looks timely and beautiful and all of a sudden, you’re confronted by these sculptures which provoke a lot of thinking. I was thinking that the next show with Helmut should be where he buries something and lets something grow because you feel that he is going in that direction. Sort of as an invisible concept trying to fill the activity of the earth.

NW: For sure, especially because this work is really rooted in the ground and the idea of having a work that almost completes itself, and does not necessarily require the audience to complete it.

Helmut Lang: What remains behind is on view at the MAK Center for Art and Architecture until May 4, 2025.

Related Content

“hl-art archive” by Helmut Lang

HELMUT LANG: The Searching Stays With You

THE TAO OF LANG: Bite-Sized Life Guidance from the Austrian Designer

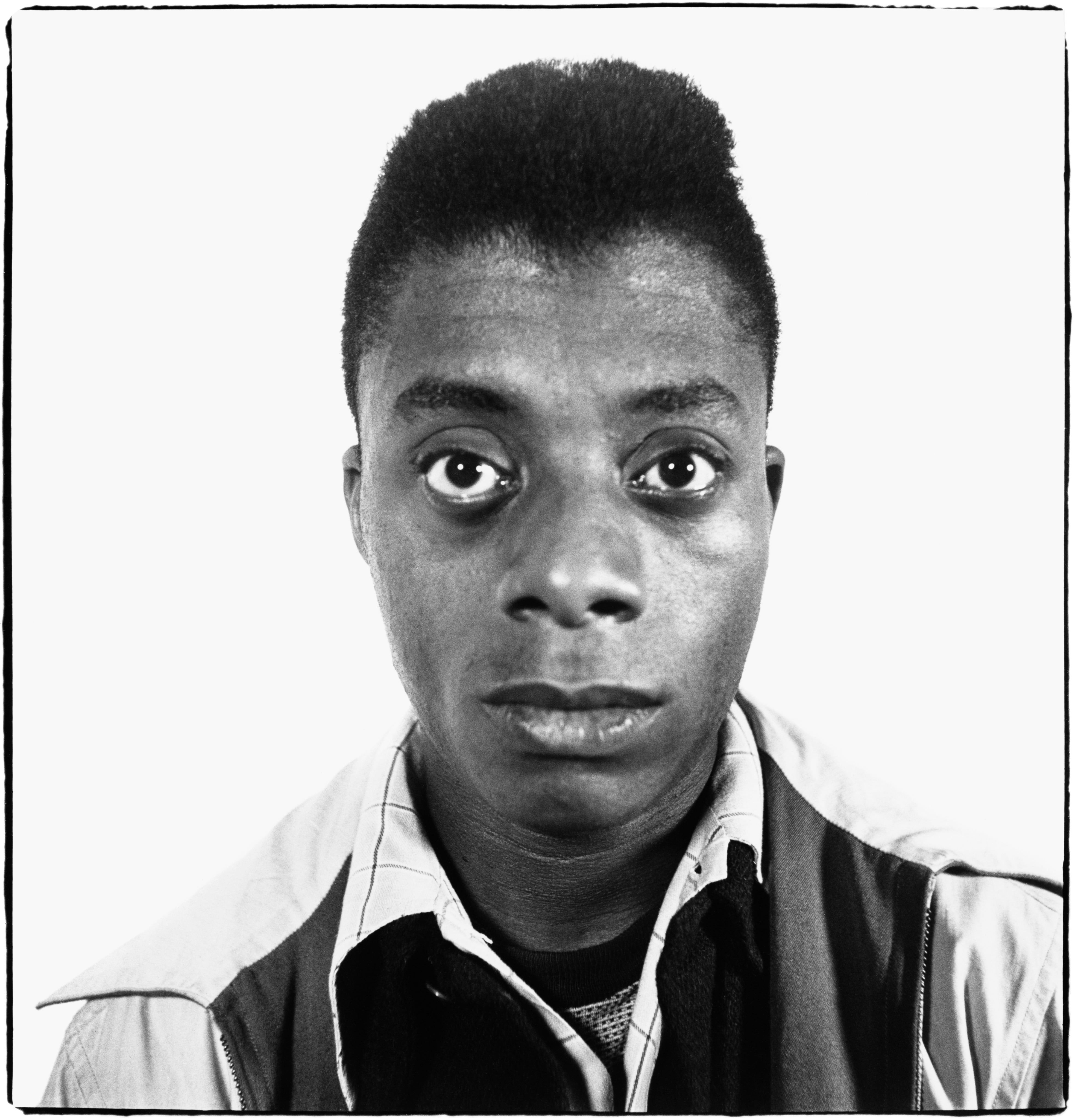

NO BLOODLESS PROPHET: Hilton Als on James Baldwin’s Body

ABC of CdG

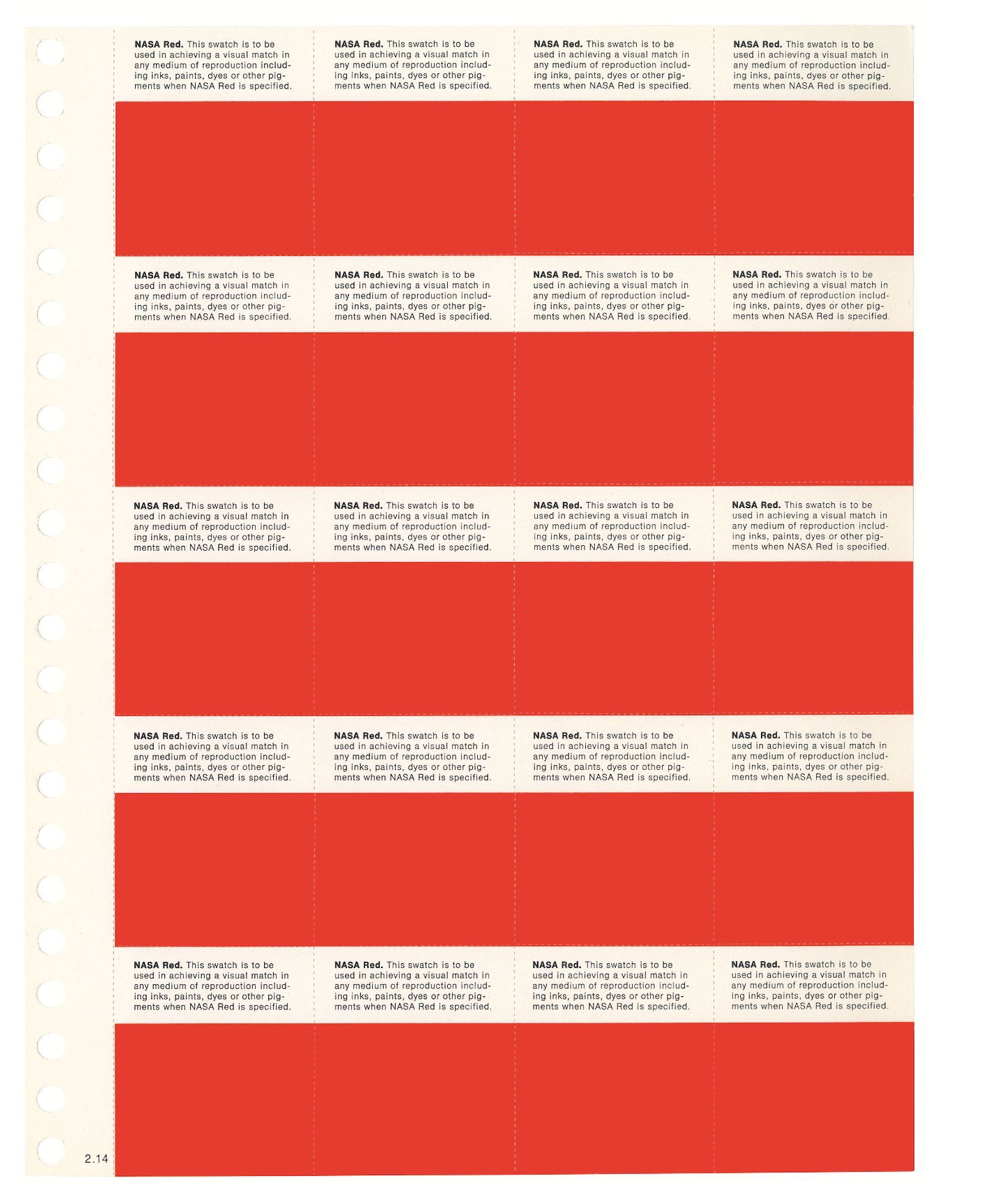

Misbehaved Modernism: When Bauhaus Arrived to American Bureaucracy and Became Acquainted with Chaos