JOHN BERGER, The Happy Centaur: Visiting a Rural Futurist

|NIKLAS MAAK

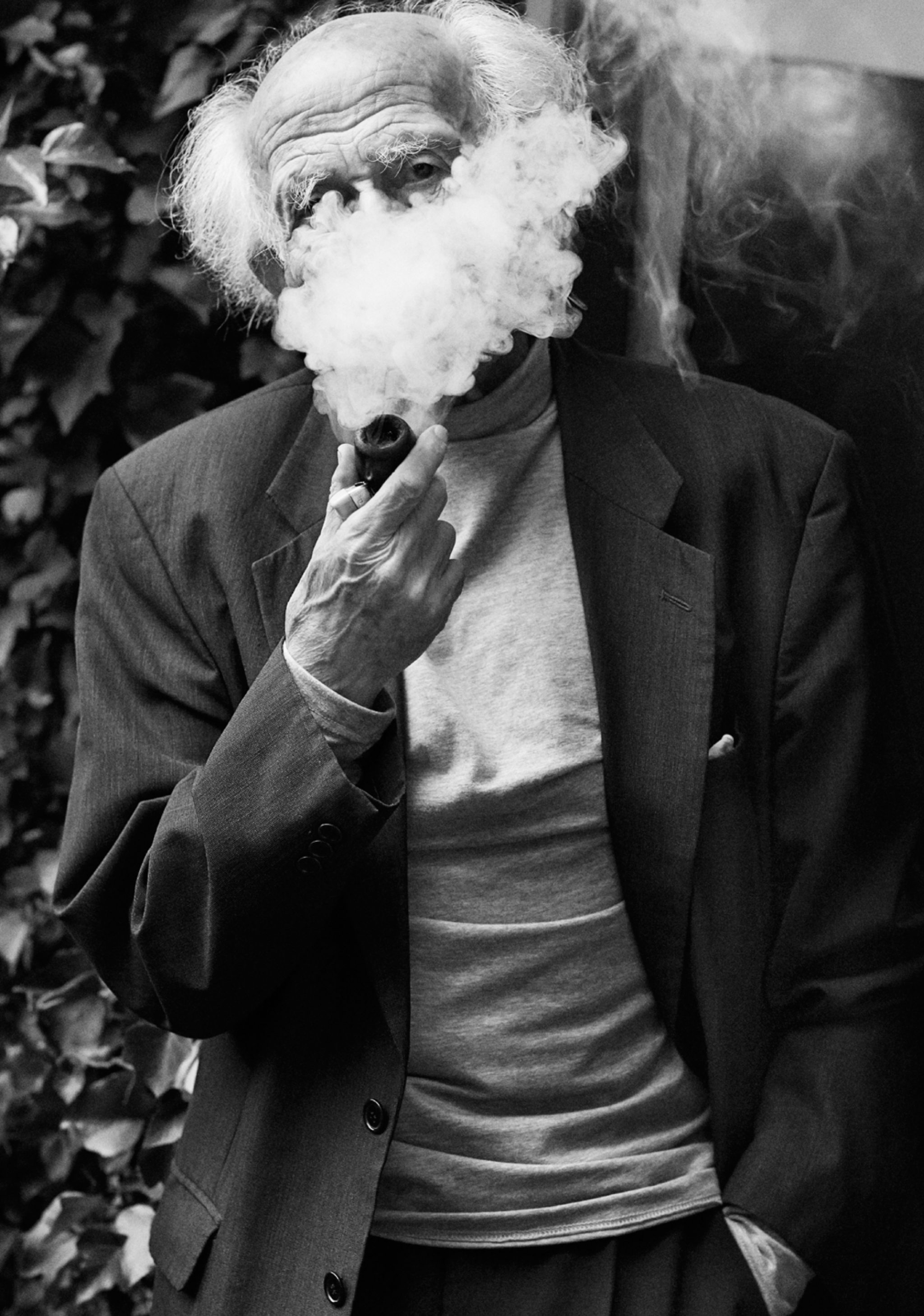

Author and artist JOHN BERGER once brought art criticism to the masses with his television series and book Ways of Seeing. When he won the Booker Prize in 1972, he donated half of the prize money to the Black Panthers and used the rest to relocate to Quincy, a small village in the French Alps, where he lived for decades.

It is the stage for The Seasons in Quincy, a film initiated by his friend Tilda Swinton that explores his secrets through four portraits. We commemorate Berger, who passed away on January 2, 2017 at the age of 90, with Niklas Maak’s portrait of the acclaimed essayist and television host from 032c issue 30.

If you want to meet John Berger, you have to take the commuter line to Paris’s southern suburbs, where the old buildings seem shocked to suddenly be part of a metropole. They are slim, single-family homes, with brick skirting, bay windows, and pointy grey roofs – houses where trackmen, gardeners, and small town mayors used to live. A sleepy, provincial pride is visible in every detail, like in the houses of Jean-Jacques Sempé’s drawings.

You buzz and John Berger opens the door. The almost 90-year-old man has snow-white hair and a warm face that resembles a desert landscape, delicately marked by erosion, weather, heat, and strong wind. His first question: “Whiskey, or wine? Whatever, we’ll have both.” Berger puts several bottles down on the table along with a caprese salad. The woman with whom he lives is from Russia and a writer. She has cooked a Russian meal with eggplants. All of a sudden, you are in the middle of a conversation and, as the caprese is still being balanced onto your plate, you are discussing the big questions of the now. Berger wants to know exactly how a server farm functions: Are there ways for people to regain control over their data? These are the kind of questions that interest him right now.

A television host and critically acclaimed essayist

On a desk in the back are Berger’s drawings. He has been drawing his whole life, even before he wrote the works that made him famous – before he taught a whole nation how to look at art on British radio and television shows such as Ways of Seeing. There, he proved that Picasso, Léger, Van Gogh, Gauguin, Modigliani, Courbet, Matisse, Goya, and Velázquez can be discussed in a way that is both intelligent and accessible.

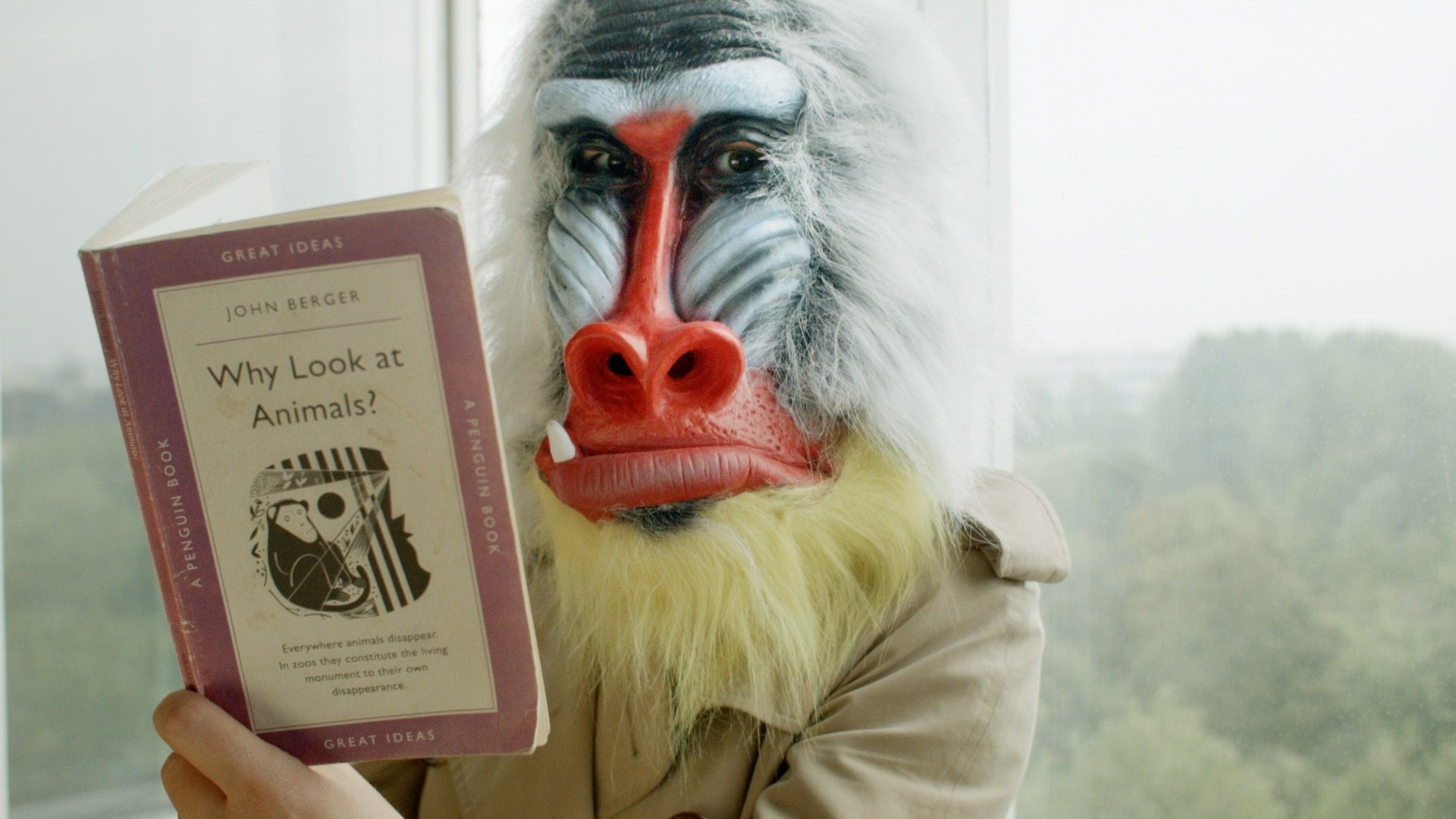

These programs showed Berger – an artist and critic who called himself a marxist – speaking about how the motifs of Renaissance art reappear in the advertisements of our time, how images manipulate our consciousness. He was able to talk about Stone Age works, and the Stone Age man’s view of his world – a world of animals where humans were the exception. Behind this ancient horizon lay another world, in which even less people and more animals lived. He was able to describe the smell of this world in a way that instantly collapsed the millennia-wide gap between it and us. He then drove a sports car and – while occasionally turning around to the camera – explained acceleration-friendly classical modernism to his viewers from the quasi-center of motion.

To be prominently present on television, while also being taken seriously as essayist and novelist, is a feat few people accomplish. In 1972, Berger’s experimental novel G. was published and unexpectedly awarded the Booker Prize. In his acceptance speech, Berger reminded dumbfounded donors of the eponymous Booker Group’s history of exploiting the Caribbean. As a kind of late compensation, he donated half his prize money to the Black Panthers. He used the rest to relocate to the Savoy Alps village of Quincy, where until recently – until the death of his partner – he lived the life of a hill farmer.

The Seasons in Quincy

Over the years, actor Tilda Swinton and directors Christopher Roth, Bartek Dziadosz, and Colin MacCabe visited Berger to direct four films about him titled The Seasons in Quincy. They document the winter in which Tilda Swinton and Berger get snowed-in and spend long nights talking about their soldier fathers, the spring in which the mother of Berger’s children passes away, all the way into fall.

Berger’s move to the alpine village was at times misunderstood as a kind of resignation, a man turning his back to urban culture, modernity even. This move to the country was interpreted as his farewell to politics, that his belief in progress had been replaced by a circular worldview in which everything – animals, the seasons – comes and goes, and humans cannot do much about it. The opposite was the case, as The Seasons in Quincy showed laconically at its premiere at the 2016 Berlinale. In the mountains, as if their alpine air had sharpened his perception, Berger developed a poetology of the political. To him, the country was not a refuge behind nostalgia’s wooden doors and comforting cottage curtains, but rather a space of opportunity, more free and less defined than overly controlled and museumized inner cities. One must think of Berger not as a modernity-adverse ruralist, but as a rural futurist.

Berger’s political critique of ideologically supported lifestyles

Decades after it was first published, A Seventh Man, a book about migrant workers that Berger wrote when he first arrived in Quincy, reads like a reflection on the contemporary struggles refugees face as they come into Europe. It is no wonder that the younger generations worship Berger like he is art criticism’s Bernie Sanders. And it is not surprising that the movies show Berger in discussion with thinkers, activists, and authors like Ben Lerner, who co-wrote the script. Berger’s renaissance is particularly prominent in Europe: Berlin’s Volksbühne staged a scenic reading of his novel A&X. The same play was just shown at the Volksbühne Basel.

Spaces of experimentation

When I called him at his Paris home, Berger’s partner picked up the phone, and I automatically asked her if her husband was there. She laughed and said: “He is not my husband. He is my big love.” When we later spoke, Berger gently rejected the term “wife,” which to his ears sounds like the barking of an anxious little dog defending his territory – This is my wife-wife-wife! He opted to replace it with “love,” or “woman,” which is less territorial and objectifying, and more affectionate. This description also accurately describes Berger: His seductive qualities lie in an extraordinary mixture of resoluteness, fearlessness, generosity, and chaleur humaine. With Berger as a guide, the countryside and its old farm buildings become a space of freedom and experimentation with life plans beyond the nuclear family organization – one in which an extended family of friends lives. A close look at the figures in Berger’s essays and novels often reveals them as utopian figures, open to emotional fluctuations. They allow themselves to love more than one person at a time, much like the figures in the writings of Fourier, who proposed a utopian rural commune called the “Phalanstery.”

Berger’s poetology as a thinking model

The Seasons in Quincy shows how the almost 90-year-old Berger remains as relevant to the present as an emerging new thinker. Berger does not celebrate an extended farming family and its communal rituals in a catalog-esque aestheticization of pre-modern everyday life, but rather in a political criticism of ideologically supported lifestyles. It is a critique of the efficiency-oriented reduction of the citizens of late capitalism to nuclear families, or singleness absorbed in self-optimization.

When Berger picks up a potato to talk about it, he makes it look like a wondrous comet from the future that crashed into the present. When Berger writes about time and memory, he is taking a run up to an as-of-now indescribable future. Remembering the dead and their suffering, battles, and hopes, Berger is creating complicity with those not yet born. In the concurrence of those present, gone, and not-yet-present, he develops a poetology that is aware of the necessity to speculate on possible futures in a time where Google, Amazon, Facebook, and other companies make a fortune off speculating what we might want to do, or buy, or be in the future. By evaluating the data they gather today, and by trying to predict our future desires based on this knowledge, they create a speculative future version of us. They are manipulating our future selves. They attack us from our future. The only chance to stay independent and sovereign might be to hide deep in the past – or to preempt their predictions in order to outline our future identities today. For this adventure, Berger’s poetology is a helpful thinking model.

Berger’s thinking at a time when the city and its former promises are in a deep crisis

Cities have always been Janus-faced, both a reflection of the political and economic realities of their time and the utopian negation of these realities. Our awareness of this seems to have disappeared, and our discourse on architecture has degenerated into either a blind faith in technology, or a ferocious rejection of progress. On the one hand, there is the “Google City” that is gradually becoming totally subordinated to the Internet. Today, Google Maps already guides its users to those businesses that pay the most for their advertising, thereby actively shaping the economic texture of cities, where houses, cars, and human beings may soon actually be controlled by algorithms. Yet opposing this technological ideal of a digitally interconnected city is a nostalgic movement that is essentially hostile towards technology. In expensive neighborhoods, it manifests as a kind of crabbed, anti-modern ruralism, with bars where bearded waiters serve handmade bread on boards they cut themselves. In architectural theory, it can be found in a fatuous enthusiasm for the self-organization processes of Latin American favelas. In its apolitical and purely formal enthusiasm for a supposedly bottom-up urbanism, it forgets that slum settlements such as the Torre de David in Caracas were run by mafia dons, and that the absence of the state does not automatically generate a peaceful, self-governing community, but enables the opposite: a violent world where the weakest members of society have no protection.

The city as a field of freedom and experimentation

The influx of refugees has forced authorities, citizens, and theorists to rethink the city as well as the long-neglected countryside. Millions of people will have to be accommodated in the city centers, either on the roofs of office buildings, in the spaces in front of or behind hotels, in transformed buildings, or in newly built homes. Berlin is about to build 45,000 housing units in the next few years in nine new neighborhoods. The street life that was gradually driven from our inner cities by a mixture of office workers and tourists might soon return with the same vibrancy and profusion of life that can be found in photographs of Berlin from the 1920s, when the city received hundreds of thousands of Eastern European refugees.

But at the same time, large numbers of people – including, but not only, refugees – could move to our half-empty small towns and villages to set up micro-factories, decentralized places that produce new products independently of the economic system of large corporations. These new, futuristic cooperatives could emerge in opposition to existing economic players and be supported by a highly pressurized politics. They would promote integration and the development of a counter-system to the contemporary urbanity controlled by digital corporations. It could emerge as a form of resistance against the supposedly inevitable state of total surveillance and commercial control – a resistance that is not restricted to the sullen rejection of all forms of technology, but rather one that co-opts them for its own ends. Cities are defined by public life, and public life by the exchange of goods and information. For a while now, an exchange of this kind, using mobile telephone communication, has been conducted among a number of small experimental communes in France that operate farms. These communes supply each other with food and information, organize protests and meetings, and create a parallel network to the established one: a new form of trans-urbanity.

What is striking about this is how far creative embedding in systems of communication has progressed, how sophisticated the co-option and misuse of them has become, and how easily control mechanisms can be dislodged by devices like the Tor browser. One can also use Facebook for information exchange with- out revealing too much about oneself. We do not have to connect intelligent houses to large data streams. We could also connect them to a self-sufficient local network that is inaccessible to large corporations such as Google. Connecting these micro-networks to bypass the large data gatherers will be one of the most important challenges of the future. It will be an essential technological condition for communes that are futuristic rather than nostalgic, where technology will not entail giving up freedom in favor of security. Rather, it will guarantee both.

Humans in nature instead of human nature

In one of his most touching texts, Berger describes painting his dying father, tracing his features as he is vanishing: “Of all the things I saw, only this drawing would remain … As I was sketching his mouth, his eyebrows, and eyelids, as their highly characteristic forms appeared as lines on my white paper, I felt the history and experience that had shaped them.” In this text, too, Berger defines art’s potential as an act of corriger la fortune – its unwillingness to accept the passing of time and things, the way it pries a part away from it to carry it into the future, and through that makes the future possible, thinkable, and visible. The features of his dead father mirror a possible future, too.

The Seasons in Quincy is also a movie about the passing of time. Its four episodes span many years, not just one. Berger grows older. His partner dies as the team is about to shoot. What remains are Berger’s unflinching attempts to distinguish nature and inevitability from things that are effected by humans. He is concerned with humans and nature, not a so-called human nature.

Berger shows that many phenomena that have been essentialized as natural and inescapable – from family values to total Internet surveillance – are politically or economically intended. Nature itself presents alternatives. He wrote about the urbanite’s simultaneously brutal (factory farming, cheap meat) and sentimental (pets, zoos) relationship to animals, and their lack of understanding for a farmer, who feeds and loves an animal, and then enjoys eating it. One of the movies relates Berger’s relationship to animals to philosopher Jacques Derrida’s interest in the animal. This cineast double-ignition shines light on the ethics of respect that preceded Berger’s critique of factory farming, imagining the animal as man’s dignified companion. The animal is thought of here as a coexisting being that may be strange, peculiar, and unknowable.

The last of the four films shows Berger, who rode motorcycles his whole life, cruising away on his hog. He moved his Japanese bike to Paris along with him to the slim house he and an old love now live in. When we met Berger, he explained that he only rides it around the city and its surroundings these days. His partner sits behind him as he speaks. “He is joined at the hip with his bike. It becomes a part of his body,” she says. Two old people tightly embracing on a motorcycle, accelerating through the streets of Paris: Is there a more modern depiction of a successful life? You have to imagine John Berger, who will turn 90 this year, as a happy centaur.

Credits

- Text: NIKLAS MAAK

- Photography: SANDRO KOPP